Sikkim the Place and Sikkim the Documentary: Reading Political History Through the Life and After-Life of a Visual Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

Sikkim State Development Programme

SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 NIEPA DC llllllllllll D00458 - i S - > V Sub. r-'s’-r r '2 in$ U n i t , Kai:.-. ’ ' f Educatlon£ P k; __ ,i£i;fa'dofi 17-f,S -^Aurb#^ N ew PelBi-1100tt€ DOC. No../) 1301:6...............................•••/•......... CONTENTS page No. SSI. No. Subject I 1. Introduction 1 2. Agriculture 12 3. Land Reforms................................................................ 13 4. Minor Irrigation............................................................ 14 5. Soil Conservation............................................................... 17 6. Food & Civil Supplies ................................................. 7. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development ... 18 22 8. Fisheries and Wild L i f e .............................. 25 9. Forest ............... ................................................. 10. Panchayats........................... ..................................... 29 Co-opeTation ............................................................ 30 12. Flood Control .................................... ....................... 33 13 Power Development ................................................ 34 14. In d u stries.................................................... 38 15. Mining & Geology ................................................ 43 16. Roads & Bridges .......................... 45 17. Road Transport ......................... ........................ 55 18. Tourism ....................................................................... -

April-June, 2014

For Private Circulation only SIHHIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 6 Issue No.2 April-June, 2014 ~ 8 . STATE MEET OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS & DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITIES 26th APRIL, 2014 AUDITORIUM, HIGH COURT OF SIKKIM, GANGTOK ORGANISED BY: SIKKIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY Editorial Board Hon'ble Shri Justice Narendra Kumar Jain, Chief Justice, High Court of Sikkim and Patron-in-Chief, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Hon'ble Shri Justice Sonam P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Compiled by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division-11 and Member Secretary, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Quarterly newsletter published by Sikkim State Legal Services Authority, Gangtok. MEETING Wlnl niE PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS OF NORTH DISTRICT A meeting with the Principals of Schools and PLVs of North District was held on 5111 April, 2014 at ADR Centre, Pentok, Mangan. The meeting was chaired by Hon'ble Shri Justice S.P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim SLSNMember, Central Authority, NAI..SA. The mode of setting up of Legal Uteracy Clubs under the NAI..SA (Legal Services Clinics in Universities, Law Colleges Hon'ble Shrl Justice S.P. Wangdl, Exet;utJoe Chalrman, and Other Institutions) Scheme, 2013 was discussed Sikkim SLSA chairing the meeting during the meeting. The meeting was also attended by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division - 11/Member Secretary, Sikkim SLSA, Shri N.G. Sherpa, Registrar, High Court of Sikkim, Shri Jagat Rai, District & Sessions Judge, North/Chairman, DLSA (North), Shri Benoy Sharma, Civil Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate/Secretary, DLSA (North), Mangan, Mrs. -

P30-31S Layout 1

30 Established 1961 Wednesday, November 29, 2017 Lifestyle Features Photo shows the Crenshaw district in Los Angeles, California, where actress Meghan An exterior view of the Immaculate Heart High School in Hollywood, California where Britain’s Prince Harry and his fiance US actress Meghan Markle pose for a photograph Markle was reported to have grown up. — AFP actress Meghan Markle was educated. in the Sunken Garden in west London following the engagement announcement. Meghan Markle follows Grace Kelly in abandoning acting eghan Markle says acting will take a back seat will remember her as a working TV actor rather than an Markle will be the first American welcomed into the roy- Bose said she expected Markle to follow other members of when she marries Prince Harry, following the exam- celebrity or a Hollywood star,” Sehdev, bestselling author of als since Wallis Simpson-famously also a divorcee-but will the family in pursuing charitable activities. Mple of screen icon Grace Kelly who abandoned “The Kim Kardashian Principle,” told AFP. He added that probably not, in fact, be a princess. What is far more likely, “Well before meeting Prince Harry, Markle already demon- Hollywood to marry into royalty. The 36-year-old has Britain’s first mixed-race royal could nevertheless inspire the say experts, is that the couple become a duke and duchess, strated a serious interest and commitment to social justice initia- starred in legal drama “Suits” since 2011, but is likely to shed British TV industry to create more leading roles for actors of like William and Kate. As well as starring as paralegal Rachel tives, as a World Vision Global Ambassador and an advocate for many outside interests as she joins the color. -

Commoners Who Married Royals

Commoners who married Royals HOPE COOKE LADY DIANA SPENCER Hope was a 20-year-old Sarah Lawrence College Arguably the most popular princess in modern history, Diana freshman traveling through India when she met Spencer became Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales Palden Thondup Namgyal, the Crown Prince of when she married Prince Charles (who previously dated Sikkim (a small Himalayan nation) back in 1959. Diana’s older sister, Lady Sarah) at only 19 years old in 1981. When they married in 1963, she became Gyalmo of Though her family was part of the British aristocracy, and she the 12th Chogyal (or Queen Consort of the 12th held the title of “Lady” once her dad became an Earl, Diana RITA HAYWORTH King) of Sikkim. Hope and her husband (who was not technically considered royalty at the time of her The old Hollywood icon was married KENDRA SPEARS divorced in 1980) wound up being the very last marriage. five times before her death at the Kendra Spears was a successful Queen Consort and King of Sikkim, which was age of 68. One of those five LEE RADZIWILL runway fashion model for years annexed by India and became the 22nd Indian marriages was to Prince Aly Khan, Lee (born Caroline Lee Bouvier) is the before marrying Prince Rahim Aga state in 1975. the Italian-born son of Aga Khan younger sister of Jackie Kennedy, the late Khan in 2013, at the age of 25. She (the Imam of Ismaili Muslims and a former first lady and widow of President John has since become known as descendant of the Prophet F. -

Princess Pema Tsedeun of Sikkim (1924-2008) Founder Member, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology 1

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 195 PRINCESS PEMA TSEDEUN OF SIKKIM (1924-2008) 1 FOUNDER MEMBER, NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY ANNA BALIKCI -DENJONGPA Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Princess of Sikkim, Pema Tsedeun Yapshi Pheunkhang Lacham Kusho, passed away in Calcutta on December 2, 2008 at the age of 84. Princess Pema Tsedeun was born on September 6, 1924 in Darjeeling, the daughter of Sir Tashi Namgyal, K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E. (1893-1963), the eleventh Chogyal of Sikkim, and Maharani Kunzang Dechen Tshomo Namgyal, the elder daughter of Rakashar Depon Tenzing Namgyal, a General in the Tibetan Army. She was born in a world when the Himalayan Kingdom of Sikkim, established by her ancestors in the 1640s, was still a protectorate of the British Empire, and when Tibet was still ruled by the 13 th Dalai Lama. Educated at St-Joseph’s Convent in Kalimpong, she married Sey Kusho Gompo Tsering Yapshi Pheunkhang (1918-1973) of the family of the 11 th Dalai Lama in October 1941. Her husband was the Governor of Gyantse and his 1 Reproduced from Now! 20 December 2008 with some modifications. 196 ANNA BALIKCI -DENJONGPA father Sawang Chenpo Yabshi Pheuntsog khangsar Kung, was the oldest of the four Ministers of Tibet. She travelled to her husband’s house in Lhasa on horseback, retreating to her palanquin when going through towns. Together, they had three daughters and a son. Lacham Kusho once related to me the circumstances of her marriage: When I got married, my father didn’t interfere. Marriage was up to me. The Pheunkhang family wanted a Sikkimese princess for their eldest son. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE of SAI Manoj Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2994 ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE OF SAI Manoj Dr. K.S. Will the Minister of YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS be pleased to state: (a) whether SAI is upgrading its training infrastructure in its centres; and (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the names of centres, where training is giving for swimming particularly in Kerala ? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) IN THE MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS (SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER) (a) Yes, Sir. (b) A list containing Status of upgradation/creation of Sports Authority of India`s sports Infrastructure during the last three years is placed at Annexure-I. The talented sportspersons under SAI Schemes are imparted regular Swimming training in the following Centres:- Under NATIONAL SPORTS TALENT CONTEST (NSTC) Scheme (i) St. Joshope Indian High School, Bangalore (ii) Tashi Namgyal Academy, Gangtok (iii) Bhonsla Military School, Nasik (iv) Don Bosco High School, Guwahati (v) Moti Lal Nehru School of Sports, RAI (Sonepat) Under ARMY BOYS SPORTS COMPANY (ABSC) Scheme (i) MEG Centre, Bangalore (ii) BEG Centre Kirkee (Pune) Under SPECIAL AREA GAMES (SAG) Scheme (i) SAG Agartala (ii) SAG Imphal Under SAI TRAINING CENTRE (STC) Scheme (i) STC Kolkata (ii) STC Gandhinagar (iii) STC Ponda (iv) STC Guwahati (v) STC Trichur Under CENTRE OF EXCELLECE (COX) Scheme (i) Kolkata (ii) Gandhinagar In the State of Kerala, Swimming is a regular discipline at STC Trichur where training is imparted. In addition swimming pools are available at Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Swimming Complex, New Delhi, Netaji Subhash National Institute of Sports, Patiala and SAI Southern Region Centre at Bangalore. -

Satyajit Ray's Documentary Film “Rabindranath”

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH, VOL. I, ISSUE 6/ SEPEMBER 2013 ISSN 2286-4822, www.euacademic.org IMPACT FACTOR: 0.485 (GIF) Satyajit Ray’s Documentary Film “Rabindranath” : A Saga of Creative Excellence RATAN BHATTACHARJEE India Satyajit‟s Ray’s documentary film „Rabindranath‟ was a saga of creative excellence. Its wide range of conception is simply amazing. It is something more profound than a mere documentary. Ray was conscious that he was making an official portrait of India's celebrated poet and hence the film does not include any controversial aspects of Tagore's life. However, it is far from being a propaganda film. In his poem Matthew Arnold once paid his tribute to Shakespeare in the ever inimitable words: “Others abide our question. Thou art free. /We ask and ask: Thou smilest and art still,/Out-topping knowledge.” This is equally true of Satyajit Ray‟s Tagore. We ask and go on asking and Tagore smiles and is „stillout-topping knowledge‟. In 1623 the great Shakespearean editors did their fantastic job of publishing in the Folio edition posthumously the 36 out of the 37 plays. Almost comparable to this outstanding editing venture is the task undertaken by Satyajit Ray FASC (Film and Study Center) to develop its most comprehensive archive on the worksof Satyajit Ray. The total number of Ray films like Shakespeare‟s dramas is 37. „Rabindranath‟, the 54 min B/W documentary film directed by Satyajit Ray was a saga of creative excellence for its wide range of conception .Tagore is revered by the world‟s 250 million Bengali speakers in India and neighbouring 901 Ratan Bhattacharjee – Satyajit Ray’s Documentary Film “Rabindranath”: A Saga of Creative Excellence Bangladesh. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

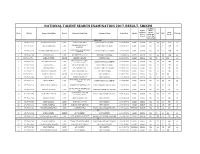

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status Residence (Please Total Sl

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status residence (please Total Sl. No. Roll No. Name of Candidates District Address of Candidates Address of School School Code Gender SAT MAT LT Marks (Rural/ verify and Marks Urban) attach the certificate) MERIT LIST 1 17170001202 INDRA BDR CHETTRI EAST PADAMCHEY EAST PADAMCHEY SEC SCHOOL 11040802902 MALE URBAN NIL 73 37 110 29 QRNO 6B /402 SUNCITY 2 17170001027 CHIRAG MARAGAL EAST ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 MALE URBAN NIL 72 37 109 37 RANIPOOL 3 17170001213 TSERING PHUNTSOK BHUTIA EAST TSHERING NORBU FL SHOP OPP/D/VILLA 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 68 40 108 43 CHANDMARI TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 4 17170001028 BHAVANA RAI EAST NO I DET ECCIU C/O 17 ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 68 37 105 39 5 17170003072 SUNIL CHETTRI SOUTH KEWZING SOUTH KEWZING SSS 11030205001 MALE RURAL NIL 72 32 104 28 ICICI ATM BLD OFF ENTEL 6 17170001210 PRANISH SHRESTHA EAST TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 65 35 100 37 MOTERS TADONG 7 17170001030 RANI KUMARI EAST STN HQ NEW CANTT GTK ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 67 32 99 40 8 17170001063 ANUSHA SUNAR EAST JNV PAKYONG EAST MIDDLE CAMP SEC SCHOOL 11040604701 FEMALE RURAL NIL 57 42 99 39 9 17170001172 BISWADEEP SHARMA EAST TAKTSE BOJOGARI EAST SIR TNSS SCHOOL 11040300801 MALE RURAL NIL 60 36 96 40 10 17170003105 BANDITA CHETTRI SOUTH MELLI KERABARI SOUTH JNV RAVONGLA 11030207301 FEMALE RURAL NIL 62 33 95 41 11 17170001066 NEHAL DAS EAST RONGLI BAZAR EAST JNV PAKYONG 11040100703 MALE URBAN -

Chapter 8 Sikkim

Chapter 8 Sikkim AC Sinha Sikkim, an Indian State on the Eastern Himalayan ranges, is counted among states with Buddhist followers, which had strong cultural ties with the Tibetan region of the Peoples’ Republic of China. Because of its past feudal history, it was one of the three ‘States’ along with Nepal and Bhutan which were known as ‘the Himalayan Kingdoms’ till 1975, the year of its merger with the Indian Union. It is a small state with 2, 818 sq. m. (7, 096 sq. km.) between 27 deg. 4’ North to 28 deg 7’ North latitude between 80 deg. East 4’ and 88deg. 58’ East longitude. This 113 kilometre long and 64 kilometre wide undulating topography is located above 300 to 7,00 metres above sea level. Its known earliest settlers, the Lepchas, termed it as Neliang, the country of the caverns that gave them shelter. Bhotias, the Tibetan migrants, called it lho’mon, ‘the land of the southern (Himalayan) slop’. As rice plays important part in Buddhist rituals in Tibet, which they used to procure from India, they began calling it ‘Denjong’ (the valley of rice). Folk traditions inform us that it was also the land of mythical ‘Kiratas’ of Indian classics. The people of Kirati origin (Lepcha, Limbu, Rai and possibly Magar) used to marry among themselves in the hoary past. As the saying goes, a newly wedded Limbu bride on her arrival to her groom’s newly constructed house, exclaimed, “Su-khim” -- the new house. This word not only got currency, but also got anglicized into Sikkim (Basnet 1974).