Pirating Mare Liberum (1609)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heinrich Wilhelm Hahn

In diesem vierten Buch sind die Drucker und Druckereyverwandte aufgeführt, deren Name mit »H«, »I«, »J« oder »K« beginnt. B13, 7.2017 Verzeichnis über die hier versammelten Drucker Charles Habré Salomon Hirzel Imprimerie Pascal Montaubin Heinrich Wilhelm Hahn Peder Hoeg Imprenta del Progreso William Hall Georg Hoffgreff Isabella von Kastilien Johann Haller Raphael Hoffhalter Michael Isingrin Warren Gamaliel Harding Frans Hogenberg Isevolod Vjaceslavovic Ivanov Joel Chandler Harris Johan Höjer Frederic Eugene Ives Francis Bret Harte Katsushika Hokusai Zar Iwan IV. Wassiljewitsch William Randolp Hearst Vaclav (Wenzel) Hollar (und eine Geschichte zum Hanf) Jodocus Hondius Joseph-Marie Jacquard Charles Theodosius Heath Johannes Honterus Isaac Jaggard Jakob Hegner Jan van Hout Sigmund Jähn Gáspár Helth George Howe, Anton Jakic Aelbrecht Hendricxsz Arthur Phillip Djura Jaksic Heo Jin-su und Lachlan Macquarie Anton Jandera Johannes Herbster Joseph Howe Martynus Jankus Alexander Herzen Charles Hulpeau Johannes Janssonius Max Herzig Tom Hultgren Vaclav Jelinek Friedrich Jasper Jesuitendruckereien in Paraguay Andreas Hess Pablo Iglesia Passo Jianyang-Druckerei Hermann Hesse Imprenta de Barcina Gerard de Jode Zacharias Heyns Imprenta Real Joseph Johnson Rowland Hill Impressão Régia Lyndon Baines Johnson Jakob Friedrich Hinz Imprimerie impériale Franz Jonas Verzeichnis über die hier versammelten Drucker Kaiser Joseph II. von Österreich Karel Klíc Ernest Joyce John und Paul Knapton Izidor Imre Kner Jakob Kaiser Heinrich Knoblochtzer Nikola Karastojanov Lorenz Kober Pieter van den Keere Anton Koberger Sen Katayama Matthias Koch Gottfried Keller Friedrich Gottlob Koenig Friedrich Gottlob Keller Eliyahu Koren Johann Matthäus Voith Johann Krafft und Erben Heinrich Voelter Wilhelm Johann Krafft Wolfgang von Kempelen Guillermo Kraft Johannes Kepler Václav Matej Kramérius Henrik Keyser d.Ä. -

Una Expedición Cartográfica Por El Museo Naval

JOSÉ MARÍA MORENO MARTÍN Una Expedición Cartográfica por el Museo Naval 16 DE JUNIO DE 2011 JOSÉ MARÍA MORENO MARTÍN LICENCIADO EN FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS, ESPECIALI- DAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA, POR LA UNIVER- SIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID. EJERCIÓ SU PROFESIÓN EN LA BIBLIOTECA NA- CIONAL HASTA 1999, MOMENTO EN EL QUE PASA AL MUSEO NAVAL. ES MIEMBRO DEL GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE CAR- TOTECAS PÚBLICAS HISPANO-LUSAS IBERCAR- TO. AUTOR DE DIVERSAS PUBLICACIONES Y ARTÍCU- LOS DE TEMÁTICA ARCHIVÍSTICA Y CARTOGRÁFI- CA NAVAL. COLABORADOR EN LA EDICIÓN DE CATÁLOGOS CARTOGRÁFICOS ACERCA DE LA ARMADA ESPAÑOLA. DIRECTOR DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE CARTOGRA- FÍA Y ARCHIVÍSTICA DEL MUSEO NAVAL. UNA EXPEDICIÓN CARTOGRÁFICA POR EL MUSEO NAVAL Me gustaría agradecer su presencia hoy aquí, en esta conferencia de este nuevo ciclo organizado por la Cátedra Jorge Juan y la Universidad del Fe- rrol, y aprovechar la ocasión para invitarles a formar parte de una expedi- ción. Una expedición cartográfica por el Museo Naval, que es el título de esta ponencia. Una expedición en la que el rumbo nos lo va a marcar la his- toria de la cartografía náutica en España. Y para ilustrar nuestro viaje he preparado una pequeña selección de los mapas que se conservan en el Museo Naval y que nos situarán en todas aquellas tierras y mares surcados por la Marina Española. Y como toda ex- pedición, la nuestra tiene un punto de partida y un punto de llegada. En nues- tro caso será el mismo: el Museo Naval de Madrid. Y desde aquí comenza- mos sin más tardar nuestra singladura. -

444.1 1 China

#444.1 China Cartographer: Jodocus Hondius Date: 1606-1634 Size: 18 x 14 inches Description: The Great Wall is depicted, Korea is displayed as an Island next to a badly mis-projected Japan. The annotations beneath the land-sailing craft suggest that this is an indigenous mode of transportation. On the northwest coast of America, the annotation references the Tartar hordes which inhabit the region and names Cape Fortuna, Anconde Island, Costa de los Tacbaios, Costa Brava and Alcones. Interesting depiction of eastern and western sailing craft, a sea monster and other decorative and fanciful features. Geographically the map is an interesting array of fact and fiction. The map contains rudimentary geographical information, as there was very little actually known of the region during the early part of the 17th century. The two most prominent features of this survey are the portrayal of the peninsula of Korea and the charming illustration of China’s Great Wall, a wonder of both the ancient and modern worlds. There is also a note purporting to be the location of the palace of the emperor of China. Despite the odd elongation of the country, there are attempts to show various provinces, and seven great cities such as Canton are marked. The interior of China is dominated by several large lakes and the mythical Chiamai Lacus forms the headwaters of five large rivers in northeastern India. The northwest coastline of America appears in the upper top corner with a notation that refers to the Tartar hordes (and the deer) that inhabit the region. 1 #444.1 As prevalent in these early maps sea monsters stalk unwary ships and Hondius shows a Dutch merchant sailing on what is labeled as Chinensis Oceanus. -

The Humanist Discourse in the Northern Netherlands

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Chapter 1: The humanist discourse in the Northern Netherlands This chapter will characterize the discourse of the Leiden humanists in the first decade of the seventeenth century. This discourse was in many aspects identical to the discourse of the Republic of Letters. The first section will show how this humanist discourse found its place at Leiden University through the hands of Janus Dousa and others. -

Poems on the Threshold: Neo-Latin Carmina Liminaria

Chapter 3 Poems on the Threshold: Neo-Latin carmina liminaria Harm-Jan van Dam Introduction Imagine someone about four hundred years ago picking up a new Latin book, for instance the fourth edition of Daniel Heinsius’ poetry, published in Leiden, shown at the end of this paper. It dates from 1613, as the colophon at the end of the book states. Readers enter the book through the frontispiece or main entrance, with its promises of sublime poetry given by the crown- ing of Pegasus, and of a text so much more correct and complete according to the inscription (emendata locis infinitis & aucta) that it would be better to throw away their earlier editions. The entrance draws the reader inside to the next page where he may learn the book’s contents (indicem . aversa indicat pagina). That index is followed first by a prose Dedicatio addressed to one of the Governors of Leiden University, then by a poem in six elegiac distichs on Heinsius’ Elegies by Joseph Scaliger, a letter by Hugo Grotius ending with seven distichs, and a Greek poem of sixteen distichs by Heinsius’ colleague Petrus Cunaeus. Finally Heinsius devotes six pages to an Address Amico lectori. Then, stepping across the threshold, the reader at last enters the house itself, the first book of the Elegies.1 Many, if not most, early modern books begin like this, with various prelimi- nary matter in prose and especially in poetry. Nevertheless, not much has been written on poems preceding the main text of books.2 They are often designated 1 Respectively pp. -

Interpretative Ingredients: Formulating Art and Natural History in Early Modern Brazil

Interpretative ingredients: formulating art and natural history in early modern Brazil Amy Buono Introduction In this article I look at two early modern texts that pertain to the natural history of Brazil and its usage for medicinal purposes. These texts present an informative contrast in terms of information density and organization, raising important methodological considerations about the ways that inventories and catalogues become sources for colonial scholarship in general and art history in particular. Willem Piso and Georg Marcgraf’s Natural History of Brazil was first published in Latin by Franciscus Hackius in Leiden and Lodewijk Elzevir in Amsterdam in 1648. Known to scholars as the first published natural history of Brazil and a pioneering work on tropical medicine, this text was, like many early modern scientific projects, a collaborative endeavor and, in this particular case, a product of Prince Johan Maurits of Nassau’s Dutch colonial enterprise in northern Brazil between 1630-54. Authored by the Dutch physician Willem Piso and the German naturalist Georg Marcgraf, the book was edited by the Dutch geographer Joannes de Laet, produced under commission from Johan Maurits, and likely illustrated by the court painter Albert Eckhout, along with other unknown artists commissioned for the Maurits expedition.1 Its title page has become emblematic for art historians and historians of science alike as a pictorial entry point into the vast world of botanical, zoological, medicinal, astronomical, and ethnographic knowledge of seventeenth-century Brazil (Fig. 1). 2 Special thanks to Anne Helmreich and Francesco Freddolini for the invitation to contribute to this volume, as well as for their careful commentary. -

Good Gratifying and Renowned

WILLEM OTTERSPEER This is the story of four centuries during which Leiden University shared the fate of the Netherlands, and became representative of the most important advances in academic research. At the same time it Good is a declaration of adoration to one of Europe’s most leading international universities. On 28 December 1574, William of Orange wrote a letter to the States General of the provinces of Holland and Zeeland from the town of Middelburg. He came to Gratifying the representatives with a proposal, a dream actually, Renowed GratifyingGood and with the plan for founding ‘a good, gratifying and A CONCISE HISTORY renowned school or university’. This letter would become the first document in the archives of Leiden OF LEIDEN UNIVERSITY University, offering an apt title for this concise history. and Willem Otterspeer (1950) is Professor of University History at Leiden University. Along with the present work, he is the author of a comprehensive, four- Renowned volume history of Leiden University. In addition to his roles as historian and biographer, he is also an essayist and a critic. ISBN 978-90-872-8235-6 WILLEM OTTERSPEER LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS 9 789087 282356 www.lup.nl LUP LEIDEN PUBLICATIONS LUP_OTTERSPEER_(hstryLeidnUnvrst)_rug18.7mm_v01.indd 1 26-11-15 10:38 Good Gratifying A CONCISE HISTORY OF LEIDEN UNIVERSITY and Renowned Good Gratifying A CONCISE HISTORY OF LEIDEN UNIVERSITY and Renowned WILLEM OTTERSPEER LEIDEN PUBLICATIONS Font: Gerard Unger was special professor of graphic design at Leiden University from 2006 to 2012. In 2013, he received his doctorate for his design of the Alverata font, a 21st-century European font design with roots in the Middle Ages. -

Joseph Scaliger, Isaac Casaubon and Richard Thomson Paul Botley University of Warwick

Three Very Different Translators: Joseph Scaliger, Isaac Casaubon and Richard Thomson Paul Botley University of Warwick This essay revisits some ideas on translation which I developed several years ago. They 477 were published as part of a book on Latin translation in the fifteenth and early six- teenth centuries, and one of the purposes of the present essay is to discover whether the intervening years have been kind to them. That book,Latin Translation in the Renaissance, examined the work of a number of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century translators, in particular, Leonardo Bruni, Giannozzo Manetti and Desiderius Erasmus, and suggested an alternative approach to categorising renaissance translations. It argued that in the fifteenth century ideas about translation became more sophisticated because of the proliferation of different translations of the same text. This was a new phenomenon: by and large, the Middle Ages had been obliged to make do with unique versions of a rather small number of Greek texts, and medieval scholars were seldom in a position to compare the merits of rival versions. In the fifteenth century, a number of versions of the same Greek text became available. As a consequence of this multiplication of renderings, even those who knew nothing of the original language were able to evaluate the differences between versions. Thus, in the fifteenth century, it became possible for a reader with no knowledge of Greek to deepen his understanding of a Greek author by collating a number of Latin translations of the original text. In such circumstances, the relation- ship of the translation to the other available translations was at least as important as the relationship of the translation to the original, Greek, text.1 Thinking about these relationships between these early modern translations led me to suggest that they could be placed into three broad categories, which I called replacements, competitors and supplements. -

00 Cat SHS 03 Layout 1 1/14/16 8:11 PM Page 1

Tapa SHS 3_Layout 1 1/14/16 9:40 PM Page 1 catalogue n˚3 Fine Books Travel & Exploration hs rare books & maps hs rare 3 - ˚ hs rare books & maps - 2016 catalogue n catalogue Tapa SHS 3_Layout 1 1/14/16 9:40 PM Page 2 item nº 20 item nº 35 ## 00 Cat SHS 03_layout 1 1/14/16 8:11 PM Page 1 Catalogue 3 hs rare books & maps - 2015 ## 00 Cat SHS 03_layout 1 1/14/16 8:11 PM Page 2 hs rare books san martin de tours 3190, capital federal cp 1425 argentina (+54) 911 5512 7770 email: [email protected] website: www.hsrarebooks.com by appointment only prices expressed in u.s. dollars all items are guaranteed to be complete unless otherwise noted. returns are accepted within 7 days of receipt. ## 00 Cat SHS 03_layout 1 1/14/16 8:11 PM Page 3 Index america 1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 34, 35 & 39 early exploration 6, 8, 12, 17, 21, 22 & 37 east indies 8, 16 & 17 holy land 40 horsemanship 13 & 33 languages 2, 18, 27 & 36 law 20 literature & science 5, 11, 13, 15, 18, 30, 31 & 33 maps 9, 25 & 39 mexico 11, 21, 22, 25, 28, 29, 32 & 36 piracy & navigation 1, 4, 8, 15, 24, 31 & 34 tobacco 38 hs rare books & maps []3 ## 00 Cat SHS 03_layout 1 1/14/16 8:11 PM Page 4 1. First edition of a rare work on the Pacific colonies of South America, with valuable information on British piracy in American waters alcedo y herrera, dionysio de. -

Bacchus En Christus. Twee Lofzangen Van Daniel Heinsius

Bacchus en Christus. Twee lofzangen van Daniel Heinsius Daniël Heinsius editie L.Ph. Rank, J.D.P. Warners en F.L. Zwaan bron Daniël Heinsius, Bacchus en Christus. Twee lofzangen van Daniel Heinsius (eds. L.Ph. Rank, J.D.P. Warners en F.L. Zwaan). W.E.J. Tjeenk Willink, Zwolle 1965 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/hein001lphr01_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl / L.Ph. Rank / erven J.D.P. Warners / erven F.L. Zwaan 4 Voor de jongste Daniel, P. Daniel Warners Daniël Heinsius, Bacchus en Christus. Twee lofzangen van Daniel Heinsius 5 Voorwoord Dit boek is ontstaan uit een mij door de Minister van Onderwijs, Kunsten en Wetenschappen verstrekte opdracht: de voorbereiding van een heruitgave van Daniel Heinsius' lofzangen op Bacchus en Christus. Deze voorbereiding hield mij twee jaar bezig. Voor de uitgave kreeg ik van hetzelfde Departement een subsidie, waarvoor ik hier gaarne zeer hartelijk dank. Behalve de twee genoemde hymnen leek het zinvol de opdrachten van Scriverius aan Iacob van Dyck en het betoog van Heinsius tot Scriverius gericht aan de hymnen te laten voorafgaan, zoals ook het geval is in de uitgave, die ik uit de verschillende edities koos. Mijn samenwerking met Dr. F.L. Zwaan bracht mij er toe hem te vragen de verklarende aantekeningen voor zijn rekening te nemen. Hij stelt er echter prijs op, te verklaren dat door de reeds grote omvang van het boek hij genoodzaakt was zich in zijn aantekeningen sterk te beperken en alleen de noodzakelijkste toelichting te geven. Dr. L. Ph Rank las met mij mijn commentaar door en wees me op een groot aantal plaatsen, die mijn aandacht ontsnapt waren, terwijl hij ook de indices samenstelde. -

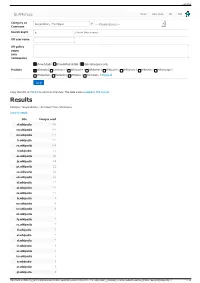

Tools.Wmflabs.Org :: Glamorous.Php

1-10-2013 GLAMorous Tools Olde tools Git Talk Category on Royal Library, The Hague or --- Popular groups --- Commons Search depth 5 (0=just this category) OR user name OR gallery pages (any namespace) Show details | Show limited details | Main namespace only Projects Wikipedia | Commons | Wikisource | Wikibooks | Wikiquote | Wiktionary | Wikinews | Wikivoyage | Wikispecies | Mediawiki | Wikidata | Wikiversity | Toggle all Do it! Copy the URL of this link to return to this view. This data is also available in XML format. Results Category "Royal Library, The Hague" has 776 images. Jump to details Site Images used nl.wikipedia 205 en.wikipedia 153 de.wikipedia 123 fr.wikipedia 111 ru.wikipedia 104 it.wikipedia 53 es.wikipedia 43 ja.wikipedia 26 pt.wikipedia 22 ca.wikipedia 21 uk.wikipedia 21 id.wikipedia 17 pl.wikipedia 14 cs.wikipedia 10 la.wikipedia 9 no.wikipedia 8 he.wikipedia 8 sh.wikipedia 7 fy.wikipedia 7 ro.wikipedia 7 fi.wikipedia 7 sl.wikipedia 7 el.wikipedia 7 tr.wikipedia 6 sv.wikipedia 6 ko.wikipedia 6 is.wikipedia 6 sr.wikipedia 6 gl.wikipedia 6 http://tools.wmflabs.org/glamtools/glamorous.php?doit=1&category=Royal+Library%2C+The+Hague&use_globalusage=1&ns0=1&depth=5&show_details=1&projects[wikipedia]=1 1 / 33 1-10-2013 hu.wikipedia 6 zh.wikipedia 6 ar.wikipedia 5 simple.wikipedia 5 da.wikipedia 5 hr.wikipedia 5 et.wikipedia 4 jv.wikipedia 4 scn.wikipedia 4 th.wikipedia 4 br.wikipedia 4 mk.wikipedia 4 eo.wikipedia 4 vi.wikipedia 4 bg.wikipedia 4 eu.wikipedia 4 oc.wikipedia 3 fa.wikipedia 3 lt.wikipedia 3 af.wikipedia 3 pcd.wikipedia -

Why Is the North Sea West of Us? Principles Behind Naming of the Seas Gammeltoft, Peder

Why is the North Sea West of Us? Principles behind naming of the Seas Gammeltoft, Peder Published in: Journal of Maritime and Territorial Studies Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Gammeltoft, P. (2016). Why is the North Sea West of Us? Principles behind naming of the Seas. Journal of Maritime and Territorial Studies, 3(1), 103-122. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 103 Why is the North Sea West of Us?: Principles behind the Naming of Seas* Peder Gammeltoft Associate Professor, Department of Nordic Research, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Abstract This article focuses on the motivations behind sea-naming, by means of examples from Europe but also elsewhere. Why do certain sea names become dominant while others retract into local forms or simply die out? The article takes us back in time to the early days of map-making and, indeed, earlier. Occurrences of sea names such as the North Sea are examined and analysed to see how they spread from an original one-language form to exist in multiple languages, and analyses them from a linguistic, geographic and nautical perspective. It is found that Seas or bodies of water in stretches of sea are named accord- ing to six main principles. Many sea-names are formally secondary names whose specific element is the name of: a) a nearby settlement name; b) a nearby island or c) a nearby country or region. In addition, a sea-name may be a formally primary name named from: d) a directional perspective, e) its appearance or f) containing the name of an explorer or a commemorated person as its specific Keywords sea-names, onomastics, place-names, historical cartography, map-making, inter- national standards The Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies Volume 3 Number 1 (January 2016) pp.