Why Is the North Sea West of Us? Principles Behind Naming of the Seas Gammeltoft, Peder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heinrich Wilhelm Hahn

In diesem vierten Buch sind die Drucker und Druckereyverwandte aufgeführt, deren Name mit »H«, »I«, »J« oder »K« beginnt. B13, 7.2017 Verzeichnis über die hier versammelten Drucker Charles Habré Salomon Hirzel Imprimerie Pascal Montaubin Heinrich Wilhelm Hahn Peder Hoeg Imprenta del Progreso William Hall Georg Hoffgreff Isabella von Kastilien Johann Haller Raphael Hoffhalter Michael Isingrin Warren Gamaliel Harding Frans Hogenberg Isevolod Vjaceslavovic Ivanov Joel Chandler Harris Johan Höjer Frederic Eugene Ives Francis Bret Harte Katsushika Hokusai Zar Iwan IV. Wassiljewitsch William Randolp Hearst Vaclav (Wenzel) Hollar (und eine Geschichte zum Hanf) Jodocus Hondius Joseph-Marie Jacquard Charles Theodosius Heath Johannes Honterus Isaac Jaggard Jakob Hegner Jan van Hout Sigmund Jähn Gáspár Helth George Howe, Anton Jakic Aelbrecht Hendricxsz Arthur Phillip Djura Jaksic Heo Jin-su und Lachlan Macquarie Anton Jandera Johannes Herbster Joseph Howe Martynus Jankus Alexander Herzen Charles Hulpeau Johannes Janssonius Max Herzig Tom Hultgren Vaclav Jelinek Friedrich Jasper Jesuitendruckereien in Paraguay Andreas Hess Pablo Iglesia Passo Jianyang-Druckerei Hermann Hesse Imprenta de Barcina Gerard de Jode Zacharias Heyns Imprenta Real Joseph Johnson Rowland Hill Impressão Régia Lyndon Baines Johnson Jakob Friedrich Hinz Imprimerie impériale Franz Jonas Verzeichnis über die hier versammelten Drucker Kaiser Joseph II. von Österreich Karel Klíc Ernest Joyce John und Paul Knapton Izidor Imre Kner Jakob Kaiser Heinrich Knoblochtzer Nikola Karastojanov Lorenz Kober Pieter van den Keere Anton Koberger Sen Katayama Matthias Koch Gottfried Keller Friedrich Gottlob Koenig Friedrich Gottlob Keller Eliyahu Koren Johann Matthäus Voith Johann Krafft und Erben Heinrich Voelter Wilhelm Johann Krafft Wolfgang von Kempelen Guillermo Kraft Johannes Kepler Václav Matej Kramérius Henrik Keyser d.Ä. -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

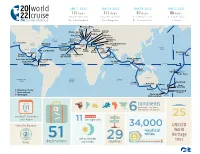

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa -

Una Expedición Cartográfica Por El Museo Naval

JOSÉ MARÍA MORENO MARTÍN Una Expedición Cartográfica por el Museo Naval 16 DE JUNIO DE 2011 JOSÉ MARÍA MORENO MARTÍN LICENCIADO EN FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS, ESPECIALI- DAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA, POR LA UNIVER- SIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID. EJERCIÓ SU PROFESIÓN EN LA BIBLIOTECA NA- CIONAL HASTA 1999, MOMENTO EN EL QUE PASA AL MUSEO NAVAL. ES MIEMBRO DEL GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE CAR- TOTECAS PÚBLICAS HISPANO-LUSAS IBERCAR- TO. AUTOR DE DIVERSAS PUBLICACIONES Y ARTÍCU- LOS DE TEMÁTICA ARCHIVÍSTICA Y CARTOGRÁFI- CA NAVAL. COLABORADOR EN LA EDICIÓN DE CATÁLOGOS CARTOGRÁFICOS ACERCA DE LA ARMADA ESPAÑOLA. DIRECTOR DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE CARTOGRA- FÍA Y ARCHIVÍSTICA DEL MUSEO NAVAL. UNA EXPEDICIÓN CARTOGRÁFICA POR EL MUSEO NAVAL Me gustaría agradecer su presencia hoy aquí, en esta conferencia de este nuevo ciclo organizado por la Cátedra Jorge Juan y la Universidad del Fe- rrol, y aprovechar la ocasión para invitarles a formar parte de una expedi- ción. Una expedición cartográfica por el Museo Naval, que es el título de esta ponencia. Una expedición en la que el rumbo nos lo va a marcar la his- toria de la cartografía náutica en España. Y para ilustrar nuestro viaje he preparado una pequeña selección de los mapas que se conservan en el Museo Naval y que nos situarán en todas aquellas tierras y mares surcados por la Marina Española. Y como toda ex- pedición, la nuestra tiene un punto de partida y un punto de llegada. En nues- tro caso será el mismo: el Museo Naval de Madrid. Y desde aquí comenza- mos sin más tardar nuestra singladura. -

Ecosystems Mario V

Ecosystems Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, Cristina Branquinho, Jean-Claude Dutay, Monia El Bour, Frédéric Médail, Meryem Mojtahid, et al. To cite this version: Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, et al.. Ecosystems. Cramer W, Guiot J, Marini K. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin -Current Situation and Risks for the Future, Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, pp.323-468, 2021, ISBN: 978-2-9577416-0-1. hal-03210122 HAL Id: hal-03210122 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03210122 Submitted on 28 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future First Mediterranean Assessment Report (MAR1) Chapter 4 Ecosystems Coordinating Lead Authors: Mario V. Balzan (Malta), Abed El Rahman Hassoun (Lebanon) Lead Authors: Najet Aroua (Algeria), Virginie Baldy (France), Magda Bou Dagher (Lebanon), Cristina Branquinho (Portugal), Jean-Claude Dutay (France), Monia El Bour (Tunisia), Frédéric Médail (France), Meryem Mojtahid (Morocco/France), Alejandra Morán-Ordóñez (Spain), Pier Paolo Roggero (Italy), Sergio Rossi Heras (Italy), Bertrand Schatz (France), Ioannis N. -

444.1 1 China

#444.1 China Cartographer: Jodocus Hondius Date: 1606-1634 Size: 18 x 14 inches Description: The Great Wall is depicted, Korea is displayed as an Island next to a badly mis-projected Japan. The annotations beneath the land-sailing craft suggest that this is an indigenous mode of transportation. On the northwest coast of America, the annotation references the Tartar hordes which inhabit the region and names Cape Fortuna, Anconde Island, Costa de los Tacbaios, Costa Brava and Alcones. Interesting depiction of eastern and western sailing craft, a sea monster and other decorative and fanciful features. Geographically the map is an interesting array of fact and fiction. The map contains rudimentary geographical information, as there was very little actually known of the region during the early part of the 17th century. The two most prominent features of this survey are the portrayal of the peninsula of Korea and the charming illustration of China’s Great Wall, a wonder of both the ancient and modern worlds. There is also a note purporting to be the location of the palace of the emperor of China. Despite the odd elongation of the country, there are attempts to show various provinces, and seven great cities such as Canton are marked. The interior of China is dominated by several large lakes and the mythical Chiamai Lacus forms the headwaters of five large rivers in northeastern India. The northwest coastline of America appears in the upper top corner with a notation that refers to the Tartar hordes (and the deer) that inhabit the region. 1 #444.1 As prevalent in these early maps sea monsters stalk unwary ships and Hondius shows a Dutch merchant sailing on what is labeled as Chinensis Oceanus. -

Wave Energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 Year Spectral Wave Hindcast

1 Wave energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 2 year spectral wave hindcast a b,∗ c 3 S. Ponce de Le´on , A. Orfila , G. Simarro a 4 UCD School of Mathematical Sciences. Dublin 4, Ireland b 5 IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB). 07190 Esporles, Spain. c 6 Institut de Ci´enciesdel Mar (CSIC). 08003 Barcelona, Spain. 7 Abstract 8 This work studies the wave energy availability in the Western Mediterranean 9 Sea using wave simulation from January 1983 to December 2011. The model 10 implemented is the WAM, forced by the ECMWF ERA-Interim wind fields. 11 The Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) data from MetOp satellite and the 12 TOPEX-Poseidon altimetry data are used to assess the quality of the wind 13 fields and WAM results respectively. Results from the hindcast are the 14 starting point to analyse the potentiality of obtaining wave energy around 15 the Balearic Islands Archipelago. The comparison of the 29 year hindcast 16 against wave buoys located in Western, Central and Eastern basins shows a 17 high correlation between the hindcasted and the measured significant wave 18 height (Hs), indicating a proper representation of spatial and temporal vari- 19 ability of Hs. It is found that the energy flux at the Balearic coasts range 20 from 9:1 kW=m, in the north of Menorca Island, to 2:5 kW=m in the vicinity 21 of the Bay of Palma. The energy flux is around 5 and 6 times lower in 22 summer as compared to winter. 23 Keywords: Mediterranean Sea, WAM model, wave energy, wave climate 24 variability, ASCAT, TOPEX-Poseidon ∗Corresponding author PreprintEmail submitted address: [email protected] Elsevier(A. -

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS of the BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA A brief introduction What are marine protected areas? Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are portions of the marine The level of protection of the Balearic Islands’ MPAs varies environment, sometimes connected to the coast, under depending on the legal status and the corresponding some form of legal protection. MPAs are used globally as administrations. In the Balearic Islands we find MPAs in tools for the regeneration of marine ecosystems, with the inland waters that are the responsibility of the Balearic dual objective of increasing the productivity of fisheries Islands government and island governments (Consells), and resources and conserving marine habitats and species. in external waters that depend on the Spanish government. Inland waters are those that remain within the polygon We define MPAs as those where industrial or semi-indus- marked by the drawing of straight lines between the capes trial fisheries (trawling, purse seining and surface longlining) of each island. External waters are those outside. are prohibited or severely regulated, and where artisanal and recreational fisheries are subject to regulation. Figure 1. Map of the Balearic Islands showing the location of the marine protection designations. In this study we consider all of them as marine protected areas except for the Natura 2000 Network and Biosphere Reserve areas. Note: the geographical areas of some protection designations overlap. THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation Table 1. Description of the different marine protected areas of the Balearic Islands and their fishing restrictions. -

SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

The 14th International Seminar on Sea Names Geography, Sea Names, and Undersea Feature Names Types of the International Standardization of Sea Names: Some Clues for the Name East Sea* Sungjae Choo (Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Kyung-Hee University Seoul 130-701, KOREA E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract : This study aims to categorize and analyze internationally standardized sea names based on their origins. Especially noting the cases of sea names using country names and dual naming of seas, it draws some implications for complementing logics for the name East Sea. Of the 110 names for 98 bodies of water listed in the book titled Limits of Oceans and Seas, the most prevalent cases are named after adjacent geographical features; followed by commemorative names after persons, directions, and characteristics of seas. These international practices of naming seas are contrary to Japan's argument for the principle of using the name of archipelago or peninsula. There are several cases of using a single name of country in naming a sea bordering more than two countries, with no serious disputes. This implies that a specific focus should be given to peculiar situation that the name East Sea contains, rather than the negative side of using single country name. In order to strengthen the logic for justifying dual naming, it is suggested, an appropriate reference should be made to the three newly adopted cases of dual names, in the respects of the history of the surrounding region and the names, people's perception, power structure of the relevant countries, and the process of the standardization of dual names. -

Zooplankton Communities Fluctuations from 1995 to 2005 in the Bay of Villefranche-Sur-Mer (Northern Ligurian Sea, France)

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Biogeosciences Discuss., 7, 9175–9207, 2010 Biogeosciences www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/7/9175/2010/ Discussions doi:10.5194/bgd-7-9175-2010 © Author(s) 2010. CC Attribution 3.0 License. This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Biogeosciences (BG). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in BG if available. Zooplankton communities fluctuations from 1995 to 2005 in the Bay of Villefranche-sur-Mer (Northern Ligurian Sea, France) P. Vandromme1,2, L. Stemmann1,2, L. Berline1,2, S. Gasparini1,2, L. Mousseau1,2, F. Prejger1,2, O. Passafiume1,2, J.-M. Guarini3,4, and G. Gorsky1,2 1UPMC Univ. Paris 06, UMR 7093, LOV, Observatoire oceanologique,´ 06234, Villefranche/mer, France 2CNRS, UMR 7093, LOV, Observatoire oceanologique,´ 06234, Villefranche/mer, France 3UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Oceanographie,´ Environnements Marins, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris 4CNRS, INstitute Environment Ecology, INEE, 3 Rue Michel-Ange, 75016 Paris 9175 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Received: 8 November 2010 – Accepted: 18 November 2010 – Published: 15 December 2010 Correspondence to: L. Stemmann ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 9176 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract An integrated analysis of the pelagic ecosystems of the Ligurian Sea is performed com- bining time series of different zooplankton groups (small and large copepods, chaetog- naths, appendicularians, pteropods, thaliaceans, decapods larvae, other crustaceans, 5 other gelatinous and other zooplankton), chlorophyll-a and nutrients, seawater salinity, temperature and density and local weather at the Point B coastal station (Northern Lig- urian Sea). -

SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS in the WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by DAVIS ARMSTRONG FAHLQUIST BS, Brown University

0 ~I~i7 SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by DAVIS ARMSTRONG FAHLQUIST B. S., Brown University (1950) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1963 Signature of Author Department of Geoogy and Geophysics Certified by 2%Kes~i Supervisor Accepted by Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 2 38 ABSTRACT SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by Davis Armstrong Fahlquist Submitted to the Department of Geology and Geophysics on 4 February, 1963, in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Results of seismic refraction studies conducted from the research vessels ATLANTIS and CHAIN (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution), WINNARETTA SINGER (Musee Oceanographique de Monaco), and VEMA (Lamont Geological Observatory) are presented. Depths to the Mohorovicic discontinuity vary from 11 to 14 km. at four refraction stations located in the deep water area bounded by the Balearic Islands, Corsica, and southern France; the mantle veloci- ties measured at these stations vary from 7. 7 to 8. 0 km/sec. Over- lying the high velocity material at three of these stations is a layer of material having a velocity of 6. 5 to 6. 8 km/sec and varying in thickness from 2 to 3 km. A significantly lower velocity, 6. 0 km/ sec, was measured for the layer directly overlying the mantle on the profile extending from near Cape Antibes to Corsica. All profiles in the northern part of the western Mediterranean Basin show the pres- ence of a 4 to 6 km. -

Central Water Masses Variability in the Southern Bay of Biscay from Early 90'S. the Effect of the Severe Winter 2005. ICES C

ICES CM 2006/C:26 ICES Annual Science Conference. Maastricht. September 2006 NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PREVIOUS NOTICE TO AUTHORS Central water masses variability in the southern Bay of Biscay from early 90's. The e®ect of the severe winter 2005 C¶esarGonz¶alez-Pola*y, Alicia Lav¶³nz, Raquel Somavillaz and Manuel Vargas-Y¶a~nezx Instituto Espa~nolde Oceanograf¶³a y C.O. de Gij¶on, z C.O. de Santander, x C.O. de M¶alaga * Avda Pr¶³ncipe de Asturias 70, 33212 Gij¶on,Spain, [email protected] Abstract A monthly hydrographical time series carried out by the Spanish Institute of Oceanography in the southern Bay of Biscay (eastern North Atlantic), covering the upper 1000 m, have shown local warming rates for the last 10-15 years that are much higher than the long-term ocean trend in the 20th century. At Mediterranean Water (MW) level this warming is linked to an e®ective modi¯cation of the termohaline properties but at the East North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) levels the warming was mainly related to isopycnal sinking (heave) until winter 2005. The overall picture is consistent with the fact that climatic warming has accelerated over the last few decades. The anomalous winter of 2005 in south-western Europe (extremely cold and dry) caused the lowest temperature record of the time-series 1993-2005 for the surface waters in the southern Bay of Biscay, and the mixed layer reached unprecedented depths greater than 300 m. The isopycnal level σθ = 27:1 classically used to analyze ENACW variability disappeared (outcrops further south) and as a result the hydrographical structure of the upper layers of the ENACW was strongly modi¯ed remaining in summer 2006 completely di®erent than what it was in the previous decade.