Watercraft, People, and Animals: Setting the Stage for the Neolithic Colonization of the Mediterranean Islands of Cyprus and Crete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya

Marine TurTle research and conservaTion in libya a conTribuTion To safeguarding MediTerranean biodiversiTy legal notice: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) and United Nations Environment Programme / Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP) concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. copyright: All property rights of texts and content of different types of this publication belong to SPA/RAC. Reproduction of these texts and contents, in whole or in part, and in any form, is prohibited without prior written permission from SPA/RAC, except for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. © 2021 united nations environment Programme Mediterranean action Plan specially Protected areas regional activity centre Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P.337 - 1080 Tunis Cedex – TUNISIA [email protected] for bibliographic purposes, this volume may be cited as: SPA/RAC-UNEP/MAP, 2021. Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya: A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity. By Abdulmaula Hamza. Ed. SPA/RAC, Tunis: pages 77. cover photo credit: sPa/rac, artescienza copyright of the photos: libsTP The present report has been prepared in the framework of the Marine Turtles project fnanced by MAVA. For more information: www-spa-rac.org Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity Study required and fnanced by: Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P. -

Minoan Religion

MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS MINOAN RELIGION STUDIES IN COMPARATIVE RELIGION Frederick M. Denny, Editor The Holy Book in Comparative Perspective Arjuna in the Mahabharata: Edited by Frederick M. Denny and Where Krishna Is, There Is Victory Rodney L. Taylor By Ruth Cecily Katz Dr. Strangegod: Ethics, Wealth, and Salvation: On the Symbolic Meaning of Nuclear Weapons A Study in Buddhist Social Ethics By Ira Chernus Edited by Russell F. Sizemore and Donald K. Swearer Native American Religious Action: A Performance Approach to Religion By Ritual Criticism: Sam Gill Case Studies in Its Practice, Essays on Its Theory By Ronald L. Grimes The Confucian Way of Contemplation: Okada Takehiko and the Tradition of The Dragons of Tiananmen: Quiet-Sitting Beijing as a Sacred City By By Rodney L. Taylor Jeffrey F. Meyer Human Rights and the Conflict of Cultures: The Other Sides of Paradise: Western and Islamic Perspectives Explorations into the Religious Meanings on Religious Liberty of Domestic Space in Islam By David Little, John Kelsay, By Juan Eduardo Campo and Abdulaziz A. Sachedina Sacred Masks: Deceptions and Revelations By Henry Pernet The Munshidin of Egypt: Their World and Their Song The Third Disestablishment: By Earle H. Waugh Regional Difference in Religion and Personal Autonomy 77u' Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: By Phillip E. Hammond Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol By By George D. Bond Nanno Marinatos A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam By Gordon Darnell Newby MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS University of South Carolina Press Copyright © 1993 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marinatos, Nanno. -

MIRROR MIRROR the Mind’S Mirror FILMS Seaglass 4 Restaurant 5 Outdoor Exhibits with Zarinah Agnew 7:30 P.M

AFTER DARK AFTER DARK SCHEDULE MAP PRESENTATIONS ACTIVITIES Upper Level Bay Observatory Gallery and Terrace 6 Observing Landscapes Mirrors in Technology and Art Through the Looking Glass Mirrors in Technology and Art With Sebastian Martin With the Explainers 6 With Sebastian Martin 6:30–8:30 p.m. | Bay Observatory Gallery 6:30–9:30 p.m. | Central Gallery 6:30–8:30 p.m. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2015 A Reflection on Mirrors Light Boxes and Anamorphic Mirrors The History of Mirrors 6:00—10:00 P.M. With Ron Hipschman With Explorables With Massimo Mazzotti 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. 7:00–10:00 p.m. | Central Gallery Main Level 8:30 p.m. Phyllis C. Wattis Webcast Studio BAR North Gallery MIRROR MIRROR The Mind’s Mirror FILMS SeaGlass 4 Restaurant 5 Outdoor Exhibits With Zarinah Agnew 7:30 p.m. | Kanbar Forum On Reflection East Gallery 9:00 p.m. | Kanbar Forum 4 Living Systems The History of Mirrors East With Massimo Mazzotti Corridor Contemplando la Ciudad (2005, 4 min.) Central Gallery 8:30 p.m. | Bay Observatory Gallery by Angela Reginato 5 3 Seeing & Listening Visions of a City (1978, 8 min.) by Lawrence Jordan A Reflection on Mirrors INSTALLATIONS BAR 3 With Ron Hipschman Suspended 2 (2005, 5 min.) by Amy Hicks Wattis 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. The Infinity Boxes Webcast Phyllis C. Wattis Webcast Studio Studio By Matt Elson Pier 15 (2013, 4 min.) by Michael Rudnick 6:00–10:00 p.m. | Central Gallery The Infinity Boxes By Matt Elson Visible Spectres 6:00–10:00 p.m. -

Nile Valley-Levant Interactions: an Eclectic Review

Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bar-Yosef, Ofer. 2013. Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review. In Neolithisation of Northeastern Africa, ed. Noriyuki Shirai. Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment 16: 237-247. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:31887680 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP In: N. Shirai (ed.) Neolithization of Northeastern Africa. Studies in Early Near Eastern: Production, Subsistence, & Environment 16, ex oriente: Berlin. pp. 237-247. Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review Ofer Bar-Yosef Department of Anthropology, Harvard University Opening remarks Writing a review of a prehistoric province as an outsider is not a simple task. The archaeological process, as we know today, is an integration of data sets – the information from the field and the laboratory analyses, and the interpretation that depends on the paradigm held by the writer affected by his or her personal experience. Even monitoring the contents of most of the published and online literature is a daunting task. It is particularly true for looking at the Egyptian Neolithic during the transition from foraging to farming and herding, when most of the difficulties originate from the poorly known bridging regions. A special hurdle is the terminological conundrum of the Neolithic, as Andrew Smith and Alison Smith discusses in this volume, and in particular the term “Neolithisation” that finally made its way to the Levantine literature. -

Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in Der Vormoderne Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 3 Wolfram Drews, Christian Scholl (Hrsg.) Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne ISBN 978-3-11-044483-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044548-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-044550-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2016 Walter De Gruyter GmbH Berlin/Boston Datenkonvertierung/Satz: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Druck und Bindung: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhaltsverzeichnis Wolfram Drews / Christian Scholl (Münster) Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne. Zur Einleitung — VII Transkulturelle Wahrnehmungsprozesse und Diskurse Roland Scheel (Göttingen) Byzanz und Nordeuropa zwischen Kontakt, Verflechtung und Rezeption — 3 Lutz Rickelt (Münster) Zum Franken geworden. Zum Franken gemacht? Der Vorwurf der ‚Frankophilie‘ im spätbyzantinischen Binnendiskurs — 35 Kristin Skottki (Rostock) Kolonialismus avant la lettre? Zur umstrittenen Bedeutung der lateinischen Kreuzfahrerherrschaften in der Levante -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

OAR Strategy (2020-2026)

OAR Strategy 2020-2026 Deliver NOAA’s Future OAR Strategic Plan | 1 2 | OAR Strategic Plan Contents 4 Introduction 5 Vision and Mission 5 Values 6 Organization 8 OAR’s Changing Operating Landscape 10 Strategic Approach 13 Goals and Objectives 14 Explore the Marine Environment 15 Detect Changes in the Ocean and Atmosphere 16 Make Forecasts Better 17 Drive Innovative Science 18 Appendix I: Strategic Mapping 19 Appendix II: Congressional Mandates OAR Strategic Plan | 3 Introduction Introduction — A Message from Craig McLean Message from Craig McLean The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created to include a major Line Office, Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), focused on determining the relationship between the atmosphere and the ocean. That task has been at the core of OAR’s work for the past half century, performed by federal and academic scientists and in the proud company of our other Line Offices of NOAA. Principally a research organization, OAR has contributed soundly to NOAA’s reputation as being among the finest government science agencies worldwide. Our work is actively improving daily weather forecasts and severe storm warnings, furthering public understanding of our climate future and the global role of the ocean, and helping create more resilient communities for a sound economy. Our research advances products and services that protect lives and livelihoods, the economy, and the environment. The research landscape of tomorrow will be different from that of today. There will likely be additional contributors to the sciences we study, including more involvement from the private sector, increased philanthropic participation, and greater academic integration. -

Oar Manual(PDF)

TABLE OF CONTENTS OAR ASSEMBLY IMPORTANT INFORMATION 2 & USE MANUAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS 3 ASSEMBLY Checking the Overall Length of your Oars .......................4 Setting Your Adjustable Handles .......................................4 Setting Proper Oar Length ................................................5 Collar – Installing and Positioning .....................................5 Visit concept2.com RIGGING INFORMATION for the latest updates Setting Inboard: and product information. on Sculls .......................................................................6 on Sweeps ...................................................................6 Putting the Oars in the Boat .............................................7 Oarlocks ............................................................................7 C.L.A.M.s ..........................................................................7 General Rigging Concepts ................................................8 Common Ranges for Rigging Settings .............................9 Checking Pitch ..................................................................10 MAINTENANCE General Care .....................................................................11 Sleeve and Collar Care ......................................................11 Handle and Grip Care ........................................................11 Evaluation of Damage .......................................................12 Painting Your Blades .........................................................13 ALSO AVAILABLE FROM -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

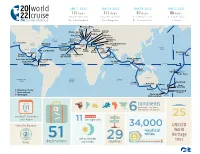

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa -

The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa

Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Introduction 20 The African archeological record of 43-28 ka as a comparison 21 A - The Aurignacian has no direct equivalent in Africa 21 B - Archaic hominins persist in Africa through much of the Late Pleistocene 24 C - High modification symbolic artifacts in Africa and Eurasia 24 Conclusions 26 Acknowledgements 26 References cited 27 To cite this article Tryon C. A. , 2015 - The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa, in White R., Bourrillon R. (eds.) with the collaboration of Bon F., Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe, Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University, P@lethnology, 7, 19-33. http://www.palethnologie.org 19 P@lethnology | 2015 | 19-33 Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Abstract The Aurignacian technocomplex in Eurasia, dated to ~43-28 ka, has no direct archeological taxonomic equivalent in Africa during the same time interval, which may reflect differences in inter-group communication or differences in archeological definitions currently in use. Extinct hominin taxa are present in both Eurasia and Africa during this interval, but the African archeological record has played little role in discussions of the demographic expansion of Homo sapiens, unlike the Aurignacian. Sites in Eurasia and Africa by 42 ka show the earliest examples of personal ornaments that result from extensive modification of raw materials, a greater investment of time that may reflect increased their use in increasingly diverse and complex social networks. -

Rocky Future for Somalia's Ancient Cave

Indian historical epic sweeps ‘Bollywood Oscars’ MONDAY, JUNE 27, 2016 37 Indian Muslims offer prayers on the third Friday of the holy fasting month of Ramadan in Lucknow, India. — AP Master of street fashion photography Bill Cunningham dead at 87 egendary New York Times fashion pho- mentary about Cunningham, Anna Wintour- Mayor Bill de Blasio’s office wrote on Twitter. Bantam Dell who was often photographed by tographer Bill Cunningham died the powerful editor of American Vogue and De Blasio added: “We will remember Bill’s Cunningham, first met the photographer LSaturday, according to the paper where one of the photographer’s muses-marveled at blue jacket and bicycle. But most of all we “many, many years ago” on a cold February he worked for nearly 40 years. He was 87. his ability to “see something, on the street or will remember the vivid, vivacious New York day during New York Fashion Week. Cunningham, whose watchful eye brought on the runway, that completely missed all of he captured in his photos.” Cunningham’s “I didn’t yet know him and he certainly did- images of New Yorkers-from the well-heeled us. And in six months’ time, that will be a “wealth of knowledge is absolutely stagger- n’t know me, but he did notice that I was inap- to unsuspecting trendsetters-to the public, trend!” Frank Rich, a former New York Times ing and he is self-effacing,” one of the found- propriately dressed for the blizzard-like condi- had been hospitalized recently after a stroke, columnist and executive producer of the HBO ing editors of InStyle magazine, Hal tions,” Cho told The Hollywood Reporter.