SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Equinor Environmental Plan in Brief

Our EP in brief Exploring safely for oil and gas in the Great Australian Bight A guide to Equinor’s draft Environment Plan for Stromlo-1 Exploration Drilling Program Published by Equinor Australia B.V. www.equinor.com.au/gabproject February 2019 Our EP in brief This booklet is a guide to our draft EP for the Stromlo-1 Exploration Program in the Great Australian Bight. The full draft EP is 1,500 pages and has taken two years to prepare, with extensive dialogue and engagement with stakeholders shaping its development. We are committed to transparency and have published this guide as a tool to facilitate the public comment period. For more information, please visit our website. www.equinor.com.au/gabproject What are we planning to do? Can it be done safely? We are planning to drill one exploration well in the Over decades, we have drilled and produced safely Great Australian Bight in accordance with our work from similar conditions around the world. In the EP, we program for exploration permit EPP39. See page 7. demonstrate how this well can also be drilled safely. See page 14. Who are we? How will it be approved? We are Equinor, a global energy company producing oil, gas and renewable energy and are among the world’s largest We abide by the rules set by the regulator, NOPSEMA. We offshore operators. See page 15. are required to submit draft environmental management plans for assessment and acceptance before we can begin any activities offshore. See page 20. CONTENTS 8 12 What’s in it for Australia? How we’re shaping the future of energy If oil or gas is found in the Great Australian Bight, it could How can an oil and gas producer be highly significant for South be part of a sustainable energy Australia. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Chapter 5: Biostratigraphy

1 • PETROLEUM GEOLOGY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Volume 5: Great Australian Bight Biostratigraphy R Morgan1, AI Rowett2 and MR White3 5INTRODUCTION . 2 TERTIARY . 21 REFERENCES . 31 MIDDLE JURASSIC TO CRETACEOUS . 2 Palynology . .21 PLATE Palynology . .2 Zonation . .21 5.1 Horologinella sp. A, B, C and D, History of zonation . .2 Wells . .21 Jerboa 1 cuttings, 2400–05 m . 12 Zonation framework . .5 Western Bight Basin: FIGURES Wells . .8 Eyre Sub-basin . .21 5.1. Major features and well locations, Great Western Bight Basin: Central Bight Basin: Australian Bight . 4 central Ceduna Sub-basin . .22 Eyre Sub-basin . .10 5.2 Middle Jurassic to Cretaceous North–central Bight Basin: Eastern Bight Basin: Duntroon and biostratigraphic zonation of the Madura Shelf . .13 eastern Ceduna Sub-basins . .22 Bight and Polda Basins. 7 Central Bight Basin: central Foraminifera . .25 5.3 Middle Jurassic to Cretaceous Ceduna Sub-basin . .14 Zonation . .25 biostratigraphy (and older stratigraphy) Polda Basin . .14 Wells . .25 of wells in the Bight and Polda Basins . 9 Eastern Bight Basin: Duntroon Western Bight Basin: 5.4 Tertiary biostratigraphic zonation of the and eastern Ceduna Sub-basins . .15 Eyre Sub-basin . 25 portion of the Eucla Basin which overlies North–central Bight Basin: Foraminifera . .18 the Bight Basin and Tertiary foraminiferal Madura Shelf . .28 events recognised in southern Australia. 26 Summary . .19 Central Bight Basin: central 5.5 Integrated microfossil and palynological Permian to Middle Jurassic . .19 Ceduna Sub-basin . .29 Tertiary biostratigraphy of wells Cretaceous . .19 Eastern Bight Basin: Duntroon and penetrating the Eucla and Bight Basins 27 eastern Ceduna Sub-basins . -

Report of Indonesia on World Country Exonyms

E/CONF.105/112/CRP.112 23 June 2017 Original: English Eleventh United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names New York, 8-17 August 2017 Item 11 of the provisional agenda* Exonyms Report of Indonesia on World Country Exonyms Submitted by Indonesia** * E/CONF.105/1 ** Prepared by Allan F. Lauder, Multamia RMT Lauder, and Rizka Windiastuti from Indonesia Overview Until recently, it has not been possible to put in place a single, standardized version for Indonesian exonyms. A priority has been to standardize the exonyms for country names. This is necessary because the use of names in school textbooks, in the media and publishing, and in other forms of communication in the public sphere demonstrate an unwanted level of variation. An examination of exonyms for country names up to the present reveals that they are formed from different types of construction. These are: Translation: The Indonesian exonym is a translation of the endonym. Example – New Zealand – Selandia Baru; Cote d’Ivoire – Pantai Gading. History: The Indonesian exonym emerged at some point in history from a variety of influences. Example – Netherland – Belanda; Nippon – Jepang. For the country names which did not have a standardized exonym, a new exonym was arrived at and approved by the Language Development and Fostering Agency (Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa), henceforth national Language Agency and the National Names Authority of Indonesia. The new exonyms mostly conform to the principle of adapting foreign names (either the endonym or the English exonym) to the phonetic rules of the Indonesian language. Examples: Ceska Republika (endonym) – Ceska; Misr (endonym) – Mesir; Seychelles (English exonym) – Seisel; Thailand – Tailandia; Kyrgyzstan (English exonym) – Kirgistan. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

EXONYMS and OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia As an Exonym in Some Languages

57-1-Special issue_acta49-1.qxd 5.5.2017 9:31 Page 99 Acta geographica Slovenica, 57-1, 2017, 99–107 EXONYMS AND OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia as an exonym in some languages. Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac, Exonyms and other geographical names Exonyms and other geographical names DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/10.3986/AGS.4891 UDC: 91:81’373.21 COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: Geographical names are proper names of geographical features. They are characterized by different meanings, contexts, and history. Local names of geographical features (endonyms) may differ from the foreign names (exonyms) for the same feature. If a specific geographical name has been codi - fied or in any other way established by an authority of the area where this name is located, this name is a standardized geographical name. In order to establish solid common ground, geographical names have been coordinated at a global level by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) since 1959. It is assisted by twenty-four regional linguistic/geographical divisions. Among these is the East Central and South-East Europe Division, with seventeen member states. Currently, the divi - sion is chaired by Slovenia. Some of the participants in the last session prepared four research articles for this special thematic issue of Acta geographica Slovenica . All of them are also briefly presented in the end of this article. KEY WORDS: geographical name, endonym, exonym, UNGEGN, cultural heritage This article was submitted for publication on November 15 th , 2016. ADDRESSES: Drago Perko, Ph.D. -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

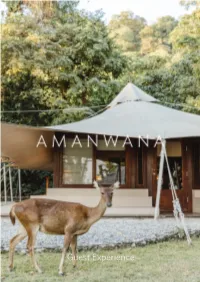

Guest Experience

Guest Experience Contents The Amanwana Experience 3 Spa & Wellness 29 During Your Stay 5 Amanwana Spa Facilities 29 A New Spa Language 30 Aman Signature Rituals 32 Amanwana Dive Centre 7 Nourishing 33 Grounding 34 Diving at Amanwana Bay 7 Purifying 35 Diving at the Outer Reefs 8 Body Treatments 37 Diving at Satonda Island 10 Massages 38 Night Diving 13 Courses & Certifications 14 Moyo Conservation Fund 41 At Sea & On Land 17 Island Conservation 41 Species Protection 42 Water Sports 17 Community Outreach & Excursions 18 Camp Responsibility 43 On the Beach 19 Trekking & Cycling 20 Amanwana Kids 45 Leisure Cruises & Charters 23 Little Adventurers 45 Leisure Cruises 23 Fishing 24 Charters 25 Dining Experiences 27 Memorable Moments 27 2 The Amanwana Experience Moyo Island is located approximately eight degrees south of the equator, within the regency of Nusa Tenggara Barat. The island has been a nature reserve since 1976 and measures forty kilometres by ten kilometres, with a total area of 36,000 hectares. Moyo’s highest point is 600 meters above the Flores Sea. The tropical climate provides a year-round temperature of 27-30°C and a consistent water temperature of around 28°C. There are two distinct seasons. The monsoon or wet season is from December to March and the dry season from April to November. The vegetation on the island ranges from savannah to dense jungle. The savannah land dominates the plateaus and the jungle the remaining areas. Many varieties of trees are found on the island, such as native teak, tamarind, fig, coral and banyan. -

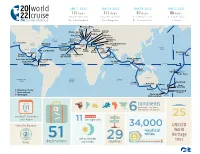

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa -

Exonyms – Standards Or from the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4

NO. 50 JUNE 2016 In this issue Preface Message from the Chairperson 3 Exonyms – standards or From the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4 Special Feature – Exonyms – standards standardization? or standardization? What are the benefits of discerning 5-6 between endonym and exonym and what does this divide mean Use of Exonyms in National 6-7 Exonyms/Endonyms Standardization of Geographical Names in Ukraine Dealing with Exonyms in Croatia 8-9 History of Exonyms in Madagascar 9-11 Are there endonyms, exonyms or both? 12-15 The need for standardization Exonyms, Standards and 15-18 Standardization: New Directions Practice of Exonyms use in Egypt 19-24 Dealing with Exonyms in Slovenia 25-29 Exonyms Used for Country Names in the 29 Repubic of Korea Botswana – Exonyms – standards or 30 standardization? From the Divisions East Central and South-East Europe 32 Division Portuguese-speaking Division 33 From the Working Groups WG on Exonyms 31 WG on Evaluation and Implementation 34 From the Countries Burkina Faso 34-37 Brazil 38 Canada 38-42 Republic of Korea 42 Indonesia 43 Islamic Republic of Iran 44 Saudi Arabia 45-46 Sri Lanka 46-48 State of Palestine 48-50 Training and Eucation International Consortium of Universities 51 for Training in Geographical Names established Upcoming Meetings 52 UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 50 June 2106 Page 1 UNGEGN Information Bulletin The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat is served by the Statistics Division (UNSD), Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. -

Atlantos D9.5. European Strategy for All Atlantic Ocean Observing System

European Strategy for All-Atlantic Ocean Observing System This report is a European contribution to the implementation of the All-Atlantic Ocean Observing System (AtlantOS). This report presents a forward look at the European capability in the Atlantic ocean observing and proposes goals and actions to be achieved by 2025 and 2030. Editors: Erik Buch, Sandra Ketelhake, Kate Larkin and Michael Ott Contributors: Michele Barbier, Angelika Brandt, Peter Brandt, Brad DeYoung, Dina Eparkhina, Vicente Fernandez, Rafael González-Quirós, Jose Joaquin Hernandez Brito, Pierre-Yves Le Traon, Glenn Nolan, Artur Palacz, Nadia Pinardi, Sylvie Pouliquen, Isabel Sousa Pinto, Toste Tanhua, Victor Turpin, Martin Visbeck, Anne-Cathrin Wölfl Design coordination: Dina Eparkhina The AtlantOS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 633211. This out- put reflects the views only of the authors, and the European Union cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of this information contained therein. 2 3 Contents Executive Summary 4 1. European strategy for the All-Atlantic Ocean Observing System (AtlantOS) 6 1.1 Why do we need a European strategy for Atlantic ocean observing? 7 1.2 Structure of this strategy 8 2. Meeting user needs: from requirement setting to product delivery 9 2.1 Recurring process of multi-stakeholder consultation for user requirements and co-design 9 2.2 The ‘blue’ value chain – products driven by user needs 10 2.3 European policy drivers 12 3. Existing and evolving observing networks and systems 13 3.1 Present capabilities and future targets 13 3.2 Role of observing networks and observing systems in the blue value chain 15 3.3 Advancing the observing system through new technology 17 4.