The Influence of Encapsulated Embryos on the Timing of Hatching in the Brooding Gastropod Crepipatella Dilatata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marine Fauna of New Zealand: the Molluscan Genera Cymatona and Fusitriton (Gastropoda, Family Cymatiidae)

ISSN 0083-7903, 65 (Print) ISSN 2538-1016; 65 (Online) The Marine Fauna of New Zealand: The Molluscan Genera Cymatona and Fusitriton (Gastropoda, Family Cymatiidae) by A. G. BEU New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 65 1978 NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH The Marine Fauna of New Zealand: The Molluscan Genera Cymatona and Fusitriton (Gastropoda, Family Cymatiidae) by A. G. BEU New Zealand Geological Survey, DSIR, Lower Hutt New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 65 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Citation according to ''World List of Scientific Periodicals" (4th edn.): Mem. N.Z. oceanogr. Inst. 65 Received for publication September 1973 © Crown Copyright 1978 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ CONTENTS Page Abstract . � 5 INTRODUCTION 5 4AXONOMY 10 Family CYMATIIDAE 10 Genus Cymatona 10 Cymatona kampyla 10 Cymatona kampyla kampyla 12 Cymatona kampyla tomlini . 18 Cymatona kampyla jobbernsi 18 Genus Fusitriton 18 Fusitriton cancellatus 22 Fusitriton cancellatus retiolus 22 Fusitriton cance/latus laudandus 23 ECOLOGY . 25 Benthic sampling programme of N.Z. Oceanographic Institute 25 Sampling methods 25 Distribution anomalies 25 Distribution 26 Distribution with depth 26 Distribution with latitude 27 Distribution with sediment type 27 Ecological conclusions 33 Dispersal times and routes of Fusitriton, and their effect on Cymatona 34 Dispersal and distribution 34 Ecological displacement of Cymatona kampyla kampyla 35 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 36 REFERENCES 36 APPENDIX 1: Station List 38 APPENDIX 2: Dimensions of Cymatona 41 APPENDIX 3: Dimensions of Fusitriton 42 INDEX 44 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. -

Auckland Shell Club Auction Lot List - 24 October 2015 Albany Hall

Auckland Shell Club Auction Lot List - 24 October 2015 Albany Hall. Setup from 9am. Viewing from 10am. Auction starts at noon. Lot Type Reserve 1 WW Many SMALL CYPRAEIDAE including the rare Rosaria caputdraconis from Easter Is. Mauritian scurra from Somalia, Cypraea eburnea white from from, New Caledonia, Cypraea chinensis from Solomon Is Lyncina sulcidentata from Hawaii and heaps more. 2 WW Many CONIDAE including rare Conus queenslandis (not perfect!) Conus teramachii, beautiful Conus trigonis, Conus ammiralis, all from Australia, Conus aulicus, Conus circumcisus, Conus gubernator, Conus generalis, Conus bullatus, Conus distans, and many more. 3 WW BIVALVES: Many specials including Large Pearl Oyster Pinctada margaritifera, Chlamys sowerbyi, Glycymeris gigantea, Macrocallista nimbosa, Pecten glaber, Amusiium pleuronectes, Pecten pullium, Zygochlamys delicatula, and heaps more. 4 WW VOLUTIDAE: Rare Teramachia johnsoni, Rare Cymbiolacca thatcheri, Livonia roadnightae, Zidona dufresnei, Lyria kurodai, Cymbiola rutila, Cymbium olia, Pulchra woolacottae, Cymbiola pulchra peristicta, Athleta studeri, Amoria undulata, Cymbiola nivosa. 5 WW MIXTURE Rare Campanile symbolium, Livonia roadnightae, Chlamys australis, Distorsio anus, Bulluta bullata, Penion maximus, Matra incompta, Conus imperialis, Ancilla glabrata, Strombus aurisdianae, Fusinus brasiliensis, Columbarium harrisae, Mauritia mauritana, and heaps and heaps more! 6 WW CYPRAEIDAE: 12 stunning shells including Trona stercoraria, Cypraea cervus, Makuritia eglantrine f. grisouridens, Cypraea -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

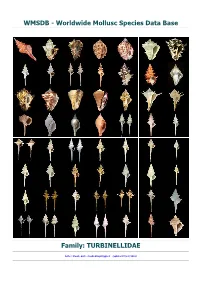

Turbinellidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINELLIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-MURICOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINELLIDAE Swainson, 1835 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=276, Genus=12, Subgenus=4, Species=91, Subspecies=13, Synonyms=155, Images=87 aapta , Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 acuminata, Turbinella acuminata L.C. Kiener, 1840 - syn of: Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) aequilonius, Fulgurofusus aequilonius A.V. Sysoev, 2000 agrestis, Turbinella agrestis H.E. Anton, 1838 - syn of: Nicema subrostrata (J.E. Gray, 1839) aldridgei , Vasum aldridgei G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969 - syn of: Attiliosa aldridgei (G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969) altocanalis , Coluzea altocanalis R.K. Dell, 1956 amaliae , Turbinella amaliae H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Hemipolygona amaliae (H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874) angularis , Coluzea angularis (K.H. Barnard, 1959) angularis , Turbinella angularis L.A. Reeve, 1847 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angularis riiseana , Turbinella angularis riiseana H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angulata , Turbinella angulata (J. Lightfoot, 1786) annulata, Syrinx annulata P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Pustulatirus annulatus (P.F. Röding, 1798) aptos , Columbarium aptos M.G. Harasewych, 1986 - syn of: Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 ardeola , Vasum ardeola A. Valenciennes, 1832 - syn of: Vasum caestus (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armatum , Vasum armatum (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armigera , Tudivasum armigera A. Adams, 1855 - syn of: Tudivasum armigerum (A. Adams, 1856) armigera , Turbinella armigera J.B.P.A. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

Arca Zebra (Mollusca Bivalvia: Arcidae) En Venezuela

Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras ISSN 0122-9761 “José Benito Vives de Andréis” Bulletin of Marine and Coastal Research Santa Marta, Colombia, 2018 47 (1), 45-66 Fauna asociada a la pesquería de Arca Zebra (Mollusca Bivalvia: Arcidae) en Venezuela Fauna associated with the fishing of Arca Zebra (Mollusca Bivalvia: Arcidae) in Venezuela Roberto Díaz-Fermín, Vanessa Acosta-Balbás Departamento de Biología, Laboratorio de Ecología. Escuela de Ciencias. Universidad de Oriente, Cumana, Venezuela. [email protected], [email protected] RESUMEN rca zebra, constituye uno de los recursos pesqueros de mayor impacto económico en el nororiente de Venezuela, ya que forma bancos de importancia comercial. Durante un periodo de nueve meses (mayo 2010- agosto 2011) se identificó, cuantificó y describió la estructura comunitaria de los organismos provenientes de la pesquería de arrastre efectuada por los pescadores de la zona; así mismo, se calculó la Abiomasa y abundancia de los diferentes grupos taxonómicos para realizar Curvas de Comparación Abundancia-Biomasa (ABC), con el objetivo de determinar el grado de afectación por la actividad de arrastre. En total se contabilizaron 3 249 organismos, pertenecientes a 130 especies, agrupadas en cinco Phylla: Mollusca, Annelida, Arthropoda, Echinodermata y Chordata. La diversidad total de Sanders fue de 122.9. Entre los taxones más diversos se encontraron los moluscos (70.87) y poliquetos (29.91). Los moluscos presentaron la mayor abundancia, seguidos de los poliquetos, crustáceos, equinodermos y ascidias. El mayor aporte en biomasa la mostraron los moluscos y equinodermos. Las especies constantes fueron: Mithraculus forceps, Phallucia nigra, Echinometra lucunter, Eunice rubra y Pinctada imbricata. -

Gastropods: of the Oligocene to Recent Genera and Description Of

Research 2006 Cainozoic , 4(1-2), pp. 71-96, February The Cantharus Group of Pisaniine Buccinid Gastropods: Review of the Oligocene to Recent Genera and Description of Some New Species of Gemophos and Hesperisternia ¹ Geerat+J. Vermeij ' Departmentof Geology, University ofCalifornia at Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA; e-mail: vermeij @geology,ucdavis. edu Received: 12 May 2004; revised version accepted 22 December 2004 The Cantharus of buccinid is in the Recent interval twelve of group pisaniine gastropods represented Oligocene to by genera, two which extinct. I review the and fossil record of these Anna 1826 are species composition, synonymy, characteristics, genera: Risso, (early Oligocene to Recent, eastern Atlantic); Cancellopollia Vermeij and Bouchet, 1998 (Recent, Indo-West Pacific); Cantharus Rdding, 1798 (Pliocene to Recent, Indo-West Pacific); Editharus Vermeij, 2001a (early Eocene to early Oligocene, Europe); Gemophos Olsson and Harbison, 1953 (late Miocene to Recent, tropical and subtropical America, one species in West Africa); Hes- peristernia Gardner, 1944 (late Oligocene to Recent, tropical and subtropical America); Pallia Gray in Sowerby, 1834 (early Mio- cene to Recent, Indo-West Pacific; one species in West Africa); Preangeria Martin, 1921 (early Miocene to Recent, Indo-West Pa- cific); Prodotia Dali, 1924 (?late Miocene to Recent, Indo-West Pacific); Pusio Gray in Griffith and Pidgeon, 1834 (?early and middle Miocene, late Miocene to Recent, eastern Pacific); Solenosteira Dali, 1890 (late Miocene to Recent, tropical America); and Zeapollia Finlay, 1927 (Oligocene to Pliocene, Australia and New Zealand). Besides many generic reassignments, I describe the basidentatus Pleistocene, Pliocene, following new species: Gemophos (early Florida); G. -

Benthic Infaunal Communities and Sediment Properties in Pile Fields Within the Hudson River Park Estuarine Sanctuary

Benthic Infaunal Communities and Sediment Properties in Pile Fields within the Hudson River Park Estuarine Sanctuary Final report to: New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program Hudson River Foundation Gary L. Taghon Rosemarie F. Petrecca Charlotte M. Fuller Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences New Brunswick, NJ 21 June 2018 Hudson Benthics Project Final report 7/11/2018 1 INTRODUCTION A core mission of the NY-NJ Harbor & Estuary Program, along with the Hudson River Foundation, is to advance research to facilitate the restoration of more, and better quality, habitat. In urban estuaries such as the NY-NJ Harbor Estuary, restoring shorelines and shallow waters to their natural or pre-industrial state is not an option in most cases because human activities have extensively modified the shorelines since the time of European contact (Squires 1992). Therefore, organizations that work to restore habitat need to dig deeper to find out what creates the most desirable habitat for estuarine wildlife. Pile fields are legacy piers that have lost their surfaces and exist as wooden piles sticking out of the sediment. Pile fields have been extolled as good habitat for fish. It is even written into the Hudson River Park Estuarine Sanctuary Management Plan that the Hudson River pile fields must be maintained for their habitat value. There is no definitive answer, however, as to why and how fish and other estuarine organisms use the pile fields. The project and results described in this report address a small portion of that larger question by assessing if the structure of the benthic community may have some bearing on how the pile fields are used as habitat. -

CHAPTER 2: Are Hypomesus Chishimaensis and H

MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE HOLARCTIC SMELT FAMILY OSMERIDAE (PISCES). by KATRIINA LARISSA ILVES B.Sc., The University of British Columbia, 2000 B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Zoology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 2007 © Katriina Larissa Ilves, 2007 ABSTRACT Biogeographers have long searched for common processes responsible for driving diversification in the Holarctic region. Although terrestrial flora and fauna have been well studied, much of the marine biogeographic work addresses patterns and processes occurring over a relatively recent timescale. A prerequisite to comparative biogeographic analysis requires well-resolved phylogenies of similarly distributed taxa that diverged over a similar timeframe. The overall aim of my Ph.D. thesis was to address fundamental questions in the systematics and biogeography of a family of Holarctic fish (Osmeridae) and place these results in a broad comparative biogeographic framework. With eight conflicting morphological hypotheses, the northern hemisphere smelts have long been the subjects of systematic disagreement. In addition to the uncertainty in the interrelationships within this family, the relationship of the Osmeridae to several other families remains unclear. Using DNA sequence data from three mitochondrial and three nuclear genes from multiple individuals per species, I reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships among the 6 genera and 15 osmerid species. Phylogenetic reconstruction and divergence dating yielded a well-resolved phylogeny of the osmerid genera and revealed several interesting evolutionary patterns within the family: (1) Hypomesus chishimaensis and H. nipponensis individuals are not reciprocally monophyletic, suggesting that they are conspecific and H. -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Molluscan marginalia: Serration at the lip edge in gastropods Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2mx5c6w9 Journal Journal of Molluscan Studies, 80(3) ISSN 0260-1230 Author Vermeij, GJ Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.1093/mollus/eyu020 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of The Malacological Society of London Molluscan Studies Journal of Molluscan Studies (2014) 80: 326–336. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu020 Advance Access publication date: 16 April 2014 Molluscan marginalia: serration at the lip edge in gastropods Geerat J. Vermeij Geology Department, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA Correspondence: G.J. Vermeij; e-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from (Received 5 September 2013; accepted 10 February 2014) ABSTRACT The shells of many marine gastropods have ventrally directed serrations (serial projections) at the edge http://mollus.oxfordjournals.org/ of the adult outer lip. These poorly studied projections arise as extensions either of external spiral cords or of interspaces between cords. This paper describes taxonomic, phylogenetic, architectural and func- tional aspects of serrations. Cord-associated serrations occur in cerithiids, strombids, the personid Distorsio anus, ocenebrine muricids and some cancellariids. Interspace-associated serrations are phylo- genetically much more widespread, and occur in at least 16 family-level groups. The nature of serration may be taxonomically informative in some fissurellids, littorinids, strombids and costellariids, among other groups. Serrated outer lips occur only in gastropods in which the apex points more backward than upward, but the presence of serrations is not a necessary byproduct of the formation of spiral sculp- tural elements. -

Mollusca, Gastropoda

Contr. Tert. Quatern. Geol. 32(4) 97-132 43 figs Leiden, December 1995 An outline of cassoidean phylogeny (Mollusca, Gastropoda) Frank Riedel Berlin, Germany Riedel, Frank. An outline of cassoidean phylogeny (Mollusca, Gastropoda). — Contr. Tert. Quatern. Geo!., 32(4): 97-132, 43 figs. Leiden, December 1995. The phylogeny of cassoidean gastropods is reviewed, incorporating most of the biological and palaeontological data from the literature. Several characters have been checked personally and some new data are presented and included in the cladistic analysis. The Laubierinioidea, Calyptraeoidea and Capuloidea are used as outgroups. Twenty-three apomorphies are discussed and used to define cassoid relations at the subfamily level. A classification is presented in which only three families are recognised. The Ranellidae contains the subfamilies Bursinae, Cymatiinae and Ranellinae. The Pisanianurinae is removed from the Ranellidae and attributed to the Laubierinioidea.The Cassidae include the Cassinae, Oocorythinae, Phaliinae and Tonninae. The Ranellinae and Oocorythinae are and considered the of their families. The third the both paraphyletic taxa are to represent stem-groups family, Personidae, cannot be subdivided and for anatomical evolved from Cretaceous into subfamilies reasons probably the same Early gastropod ancestor as the Ranellidae. have from Ranellidae the Late Cretaceous. The Cassidae (Oocorythinae) appears to branched off the (Ranellinae) during The first significant radiation of the Ranellidae/Cassidaebranch took place in the Eocene. The Tonninae represents the youngest branch of the phylogenetic tree. Key words — Neomesogastropoda, Cassoidea, ecology, morphology, fossil evidence, systematics. Dr F. Riedei, Freie Universitat Berlin, Institut fiir Palaontologie, MalteserstraBe 74-100, Haus D, D-12249 Berlin, Germany. Contents superfamily, some of them presenting a complete classifi- cation. -

Effects of Clam Aquaculture on Nektonic and Benthic Assemblages in Two Shallow-Water Estuaries

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2016 Effects Of Clam Aquaculture On Nektonic And Benthic Assemblages In Two Shallow-Water Estuaries Mark Luckenbach Virginia Institute of Marine Science JN Kraeuter D Bushek Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Luckenbach, Mark; Kraeuter, JN; and Bushek, D, Effects Of Clam Aquaculture On Nektonic And Benthic Assemblages In Two Shallow-Water Estuaries (2016). Journal Of Shellfish Research, 35(4), 757-775. 10.2983/035.035.0405 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 35, No. 4, 757–775, 2016. EFFECTS OF CLAM AQUACULTURE ON NEKTONIC AND BENTHIC ASSEMBLAGES IN TWO SHALLOW-WATER ESTUARIES MARK W. LUCKENBACH,1* JOHN N. KRAEUTER2,3 AND DAVID BUSHEK2 1Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William Mary, 1208 Greate Rd., Gloucester Point, VA 23062; 2Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory, Rutgers University, 6959 Miller Ave., Port Norris, NJ 08349; 3Marine Science Center, University of New England, 1-43 Hills Beach Rd., Biddeford, ME 04005 ABSTRACT Aquaculture of the northern quahog (¼hard clam) Mercenaria mercenaria (Linnaeus, 1758) is widespread in shallow waters of the United States from Cape Cod to the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Grow-out practices generally involve bottom planting and the use of predator exclusion mesh.