PLATFORM: Journal of Media and Communication Vol ??? Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Press Release Potsdam Declaration

Press Release Potsdam 19.10.2018 Potsdam Declaration signed by 21 public broadcasters from Europe “In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe.” A joint statement, emphasizing the inclusive rather than divisive mission of public broadcasting, will be signed on Friday 19th October 2018 in Potsdam. Cilla Benkö, Director General of Sveriges Radio and President of PRIX EUROPA, and representatives from 20 other European broadcasters are making their appeal: “The time to stand up for media freedom and strong public service media is now. Our countries need good quality journalism and the audiences need strong collective platforms”. The act of signing is taking place just before the Awards Ceremony of this year’s PRIX EUROPA, hosted by rbb in Berlin and Potsdam from 13-19 October under the slogan “Reflecting all voices”. The joint declaration was initiated by the Steering Committee of PRIX EUROPA, which unites the 21 broadcasters. Potsdam Declaration, 19 October 2018 (full wording) by the 21 broadcasters from the PRIX EUROPA Steering Committee: In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe. It has never been more important to carry on offering audiences a wide variety of voices and opinions and to look at complex processes from different angles. Impartial news and information that everyone can trust, content that reaches all audiences, that offers all views and brings communities together. Equally important: Public broadcasters make the joys of culture and learning available to everyone, regardless of income or background. -

Portionate Measure in Relation to the Objective to Be Achieved, in That The

OPINION OF MR WARNER — CASE 52/79 portionate measure in relation to the objective to be achieved, in that the prohibition in question is relatively ineffective in view of the existence of natural reception zones, or discrimination which is prohibited by the Treaty in regard to foreign broadcasters, in that their geographical location allows them to broadcast their signals only in the natural reception zone. Kutscher O'Keeffe Touffait Mertens de Wilmars Pescatore Mackenzie Stuart Bosco Koopmans Due Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 18 March 1980. A. Van Houtte H. Kutscher Registrar President OPINION OF MR ADVOCATE GENERAL WARNER DELIVERED ON 13 DECEMBER 1979 My Lords, Both raise questions of interpretation of Articles 59 to 66 of the EEC Treaty, relating to the free movement of services. Introduction Both have as their background the Of these two cases, one, Case 52/79, activities of undertakings providing comes to the Court by way of a television diffusion services in Belgium. reference for a preliminary ruling by the Essentially, such a service consists in Tribunal Correctionnel of Liège, the picking up by means of an aerial other, Case 62/79, by way of a reference television signals that have been for a preliminary ruling by the Cour broadcast over the air and distributing d'Appel of Brussels. the signals by cable to the television sets 860 PROCUREUR DU ROI v DEBAUVE of subscribers to the service. We were Counsel for the German Government, told that, from a technical point of view, but he did not press the point, nor would it is only the scale and professionalism of the overall picture have been much the operation (in particular, the size and altered if he had been right. -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Other Publications from the Center for Global Center for Global Communication Studies Communication Studies (CGCS) 4-2003 Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE Tarlach McGonagle Bethany Davis Noll Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGonagle, Tarlach; Davis Noll, Bethany; and Price, Monroe. (2003). Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE. Other Publications from the Center for Global Communication Studies. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE Abstract There are a large number of language-related regulations (both prescriptive and proscriptive) that affect the shape of the broadcasting media and therefore have an impact on the life of persons belonging to minorities. Of course, language has been and remains an important instrument in State-building and maintenance. In this context, requirements have also been put in place to accommodate national minorities. In some settings, there is legislation to assure availability of programming in minority languages.1 Language rules have also been manipulated for restrictive, sometimes punitive ends. A language can become or be made a focus of loyalty for a minority community that thinks itself suppressed, persecuted, or subjected to discrimination. Regulations relating to broadcasting may make language a target for attack or suppression if the authorities associate it with what they consider a disaffected or secessionist group or even just a culturally inferior one. -

Can Platforms Cancel Politicians?

MARTIN FERTMANN AND MATTHIAS C. KETTEMANN (EDS.) Can Platforms Cancel Politicians? How States and Platforms Deal with Private Power over Public and Political Actors: an Exploratory Study of 15 Countries GDHRNET WORKING PAPER SERIES #3 | 2021 „All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.“ Art. 1, sentence 1, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), GDHRNet Working Paper #3 2 EU COST Action – CA19143 – Global Digital Human Rights Can Platforms Cancel Politicians? How States and Platforms Deal with Private Power over Public and Political Actors: an Exploratory Study of 15 Countries edited by Martin Fertmann and Matthias C. Kettemann (LEIBNIZ INSTITUTE FOR MEDIA RESEARCH | HANS-BREDOW-INSTITUT, HAMBURG, GERMANY) Cite as: Martin Fertmann and Matthias C. Kettemann (eds.), Can Platforms Cancel Politicians? How States and Platforms Deal with Private Power over Political Actors: an Exploratory Study of 15 Countries (Hamburg: Verlag Hans- Bredow-Institut, 2021) This is GDHRNet Working Paper #3 in a series of publications in the framework of GDHRNet edited by Mart Susi and Matthias C. Kettemann. GDHRNet is funded as EU COST Action – CA19143 – by the European Union. All working papers can be downloaded from leibniz-hbi.de/GDHRNet and GDHRNet.eu CC BY SA 4.0 Publisher: Leibniz Institut für Medienforschung | Hans-Bredow-Institut (HBI) Rothenbaumchaussee 36, 20148 Hamburg Tel. (+49 40) 45 02 17-0, [email protected], www.leibniz-hbi.de Executive Summary - Terms-of-service based actions against political and state actors as both key subjects and objects of political opinion formation have become a focal point of the ongoing debates over who should set and enforce the rules for speech on online platforms. -

Jaaroverzicht 1978 Brt

BRT INSTITUUT DER NEDERLANDSE UITZENDINGEN JAAROVERZICHT 1978 BRT INSTITUUT DER NEDERLANDSE UITZENDINGEN JAAROVERZICHT 1978 TEN GELEIDE De rationalisatie van de BRT-structuren3 die in 1973 werd ingezet met de hervorming van de radio-organisatie 3 in 1975 gevolgd door de herstructurering van de televisie3 en voltooid dank zij de omroepwet van februari 1977 waar bij het Instituut van de Gemeenschappelijke Diensten (I.G.D.) werd opgeheven3 begon in 1978 volop vruchten af te werpen. Zo leidde de vlotte samenwerking tussen de cul turele en de technische diensten tot een aanzienlijke verbetering van de produktiviteit. Voor de eerste maal slaagden de financiële diensten erin de reële kostprijs van de onderscheidene radio- en televisie-produkties te berekenen; en de vergelijking met buitenlandse omroep- stations leidt tot de conclusie dat de BRT-kostprijzen aan de lage kant liggen. Bovendien kon de BRT dank zij het aandachtig volgen van de maandelijkse begrotingstoestand en ondanks een door de regering midden in het jaar opge legde besnoeiing van de toelage met ruim 2 %3 andermaal de balans 1978 met een ruim batig saldo afsluiten. Dit is ongetwijfeld het resultaat van de integrale autonomie die de BRT 3 tengevolge van de opheffing van het I.G.D.3 ook op technisch en administratief-financieel vlak ver worven heeft. De toenemende gevoeligheid voor de communautaire vraagstukken bracht de Voorzitter van de Raad van Beheer3 prof. dr . A. Verhuist3 ertoe op de persconferentie van oktober 1978 de aandacht van de openbare opinie te ves tigen op de wanverhouding tussen de opbrengst van het kijk- en luist erg eld in het Vlaamse landsgedeelte en de aan de BRT toegekende dotatie. -

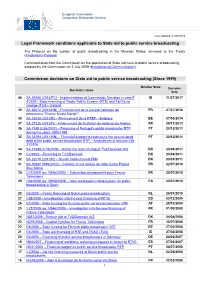

List of Public Broadcasting Decisions

European Commission Competition Directorate-General Last updated: 01/07/2019 Legal Framework conditions applicable to State aid to public service broadcasting The Protocol on the system of public broadcasting in the Member States, annexed to the Treaty (Amsterdam Protocol). Communication from the Commission on the application of State aid rules to public service broadcasting, adopted by the Commission on 2 July 2009 (Broadcasting Communication). Commission decisions on State aid to public service broadcasting (Since 1999) Member State Decision Decision name date 40 SA.39346 (2014/FC) - Implementation of Commission Decision in case E IE 11/07/2017 4/2005 - State financing of Radio Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) and Teilifís na Gaeilge (TG4) - Ireland 39 SA.36672 (2013/NN) - Financement de la société nationale de FR 27/07/2016 programme "France Media Monde" 38 SA.32635 (2012/E) – Financement de la RTBF – Belgique BE 07/05/2014 37 SA.37136 (2013/N) - Financement de la station de radio locale France FR 08/11/2013 36 SA.7149 (C85/2001) – Financing of Portugal's public broadcaster RTP PT 20/12/2011 during the years 1992-1998 35 SA.33294 (2011/NN) – Financial support to restructure the accumulated PT 20/12/2011 debt of the public service broadcaster RTP – Amendment of decision NN 31/2006 34 SA.27688 (C19/2009) - Aid for the restructuring of TV2/Danmark A/S DK 20/04/2011 33 C2/2003 – Financing of TV2/Danmark DK 20/04/2011 32 SA.32019 (2010/N) – Danish radio channel FM4 DK 23/03/2011 31 SA.30587 (N95/2010) – Création d’une station de radio locale France FR 22/07/2010 Bleu Maine 30 C27/2009 (ex. -

Service INFODOC De La RTBF Romain Dremiere

Service INFODOC de la RTBF Romain Dremiere To cite this version: Romain Dremiere. Service INFODOC de la RTBF. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. 2008. dumas-01731258 HAL Id: dumas-01731258 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01731258 Submitted on 14 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romain DREMIERE Master 1 - SID Juin 2008 Rapport de stage Service INFODOC de la RTBF rtbF- Université Charles de Gaulle Lille 3 UFR Information Documentation Information Scientifique et Technique M Master Sciences de l'Information, de la communication et du Document 1 SOMMAIRE REMERCIEMENTS p4 RESUME p5 INTRODUCTION p6 PARTIE I : Présentation du lieu de stage et des différentes missions p7 1.1 Présentation de la RTBF p7 1.2 Présentation du service INFODOC p8 1.3 Les missions réalisées plO PARTIE II : Le thésaurus plO 2.1 Aspects généraux des thésaurus pl 1 2.2 Règles générales d'indexation et de recherche avec un thésaurus pl 1 2.2.1 Définition et rôle de l'indexation. 2.3 Etapes de l'indexation pl3 2.3.1 Niveau conceptuel. 2.3.2 Niveau du langage naturel. -

Eurodoc Executive Meeting – an Exclusive Meeting Platform for Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors

EURODOC EXECUTIVE MEETING – AN EXCLUSIVE MEETING PLATFORM FOR DOCUMENTARY EXECUTIVES AND COMMISSIONING EDITORS Tuesday, 2nd of October 2018 Geneva, Eurodoc for Executives CHANGE IN PUBLIC SERVICE PLATFORM CURATING – MORE THAN ALGORHYTHM ? With Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, EBU Curation and algorithms as ways of enhancing our service are definitely something public service should take up (have taken up…), but it seems to be developing very slowly almost everywhere. The news of the planned "Alliance" of France Televisions, ZDF and RAI, or the planned joint streaming service of BBC, Channel4 and ITV make it very clear that also the European public service media have understood that the media landscape will be dominated by big international or global players. The survival for documentary programs and smaller players in this landscape will require co-operation and high quality of not only the content but also the service. We may find ourselves having to create and defend a position not within one national public service broadcaster but a conglomerate of many. LUNCH for Executives only 2.30 PM – 5 PM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION INPUT by Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, European Broadcasting Union EBU, Geneva, introducing to the « Alliance » of France Télévision, ZDF and RAI and other public initiatives followed by a discussion INTERNATIONAL CASE STUDYS by our participants from the different services such as ARTE, SRF, HBO etc. THE EURODOC EXECUTIVE’S MEETING Since 2013, Eurodoc also offers an exclusive opportunity to meet amongst Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors only. This exclusive meeting always takes place on the first day of the Eurodoc session and is curated by Anita Hugi (SRF) for Eurodoc. -

Mediawan Enters Into Exclusive Talks with on Kids & Family, the European Leader in Animation, with a View to Acquiring a Majority Stake

MEDIAWAN ENTERS INTO EXCLUSIVE TALKS WITH ON KIDS & FAMILY, THE EUROPEAN LEADER IN ANIMATION, WITH A VIEW TO ACQUIRING A MAJORITY STAKE • Mediawan and ON kids & family announce having entered into exclusive talks with a view to the former acquiring a 51% to 55% majority stake in the latter • A strategic operation for Mediawan, which will join forces with the European leader in the production of animated content with internationally reckoned global franchises like The Little Prince, Playmobil, Iron Man, Chaplin and, most recently, Miraculous Ladybug • The ON kids & family group’s co-founders, Aton Soumache and Dimitri Rassam, and the main shareholders, including Thierry Pasquet, will team up with Mediawan. Aton Soumache will also continue to manage the Group as ON kids & family’s CEO • Mediawan’s investment will be partly achieved through a capital increase allowing ON kids & family to accelerate its growth and its international positioning as a leading player in animation in Europe with worldwide recognition • ON kids & family produces major international audiovisual creations by developing emblematic brands with considerable commercial potential, and will continue to develop high-end content via the creation of powerful franchises and the management of world-renowned intellectual property Paris, December 17, 2017, 8 pm (CET) - Mediawan (Ticker: MWD – ISIN: FR0013247137), an independent European audiovisual content platform, is continuing its development by entering into exclusive talks with the shareholders of ON kids & family, a major European player in the production of animated content for children, with a view to acquiring a majority stake. Backed by a joint project and a shared vision of the Entertainment sector, Mediawan and ON kids & family want, via this strategic operation, to establish a very strong presence on the European and international markets. -

The Information of the Citizen in the Eu: Obligations for the Media and the Institutions Concerning the Citizen's Right to Be Fully and Objectively Informed

Directorate-General Internal Policies Policy Department C CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS THE INFORMATION OF THE CITIZEN IN THE EU: OBLIGATIONS FOR THE MEDIA AND THE INSTITUTIONS CONCERNING THE CITIZEN'S RIGHT TO BE FULLY AND OBJECTIVELY INFORMED STUDY ID. N°: IPOL/C/IV/2003/04/01 AUGUST 2004 PE 358.896 EN Thisstudy wasrequested by: the European Parliament'sCommittee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Thispaper ispublished in the following languages: EN (original) and DE Author: Deirdre Kevin, Thorsten Ader, Oliver Carsten Fueg, Eleftheria Pertzinidou, Max Schoenthal European Institute for the Media, Düsseldorf Responsible Official: Mr Jean-Louis ANTOINE-GRÉGOIRE Policy Unit Directorate C Remard 03 J016 - Brussels Tel: 42753 Fax: E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in August 2004. Paper copiescan be obtained through: - E-mail: [email protected] - Site intranet: http://ipolnet.ep.parl.union.eu/ipolnet/cms/pid/438 Brussels, European Parliament, 2005 The opinionsexpressed in thisdocument are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposesare authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher isgiven prior notice and sent a copy. 2 PE 358.896 EN Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Executive Summary 5 Part I Introduction 8 Part II: Country Reports Austria 15 Belgium 25 Cyprus 35 Czech Republic 42 Denmark 50 Estonia 58 Finland 65 France