CZAPSCY Czapscy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

153 AUKCJA QARRK Dobra A

1 AUKCJA DZIE¸A SZTUKI I ANTYKI 13 GRUDNIA 2007 DOM AUKCYJNY ul. Marsza∏kowska 34-50 00-554 Warszawa, tel. (22) 584 95 31 tel. (22) 584 95 24 fax (22) 584 95 26 [email protected] GALERIA GALERIA GALERIA MARSZA¸KOWSKA DESA MODERN STAROMIEJSKA ul. Marsza∏kowska 34-50 ul. Koszykowa 60/62 Rynek Starego Miasta 4/6 00-554 Warszawa 00-673 Warszawa 00-272 Warszawa tel. (22) 584 95 35 tel. (22) 621 96 56 tel. (22) 831 16 81 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] GALERIA GALERIA SALON DZIE¸ BI˚UTERII DAWNEJ NOWY ÂWIAT SZTUKI MARCHAND ul. Nowy Âwiat 48 ul. Nowy Âwiat 51 Pl. Konstytucji 2 00-363 Warszawa 00-042 Warszawa 00-552 Warszawa tel. (22) 826 44 66 tel. (22) 827 47 60 tel. (22) 621 66 69 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TERMINY NAJBLI˚SZYCH AUKCJI W 2007 ROKU: 15 grudnia – aukcja prezentów TERMINY AUKCJI W 2008 ROKU: Aukcja - Czwartek, 13 grudnia 2007, godz. 19 Auction - Thursday, December 13, 2007 at 7 pm Dzie∏a Sztuki i Antyki Sztuka Wspó∏czesna Galeria Domu Aukcyjnego Desa Unicum Desa Unicum Auction House Gallery 21 lutego 13 marca Warszawa, ul. Marsza∏kowska 34-50 Warsaw, Marsza∏kowska str. 34-50 24 kwietnia 29 maja Wystawa przedaukcyjna: Viewing: 19 czerwca 9 paêdziernika od 1 do 13 grudnia 2007 from 1 to 13 of December 11 wrzeÊnia 18 grudnia Godziny otwarcia galerii: Our gallery opening hours are: 23 paêdziernika 11-19 od poniedzia∏ku do piàtku 11am to 7pm between Monday and Friday 4 grudnia 11-16 w soboty 11am to 4pm on Saturday ok∏adka – Józef CHE¸MO¡SKI - Próba czwórki, 1878 r. -

'Politics of History'?

35 Professor Jan Pomorski Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland ORCID: 0000-0001-5667-0917 AD VOCEM WHAT IS ’POLITICS OF HISTORY’? CONCERNING POLAND’S RAISON D’ÉTAT* (ad vocem) Abstract The term ‘politics of history’ can be encountered in the narratives created by three distinct types of social practice: (1) the social practice of research (‘politics of history’ is the subject of the research, and not the practice); (2) the social practice of politics (‘politics of history’ is practiced, and may be either an instrument for gaining and retaining power, and/or an instrument for realising the state’s raison d’état); (3) the social practice of memory (where the practice of ‘politics of history’ also has a place, and is synonymous with ‘politics of memory’). The author argues that political raison d’état requires Poland to pursue an active politics of history which should be addressed abroad, and proposes that its guiding ideas should be based on three grand narratives: (1) the fundamental role of ‘Solidarity Poland’ in the peaceful dismantling of the post-Yalta system in Europe, (2) the Europe of the Jagiellonians, and (3) the Europe of the Vasas, as constructs simultaneously geopolitical and civilisational, in which Poland performed an agential function. Keywords: politics of history as a subject of research, politics of history as a subject of practice, politics of history as raison d’état Institute of National Remembrance 1/2019 36 “Whoever does not respect and value their past is not worthy of respect by the present, or of the right to a future.” Józef Piłsudski “Polishness – it is not Sarmatian-ness, it is not confined to the descent from pre-Lechite peasants and warriors; nor it is confined to what the Middle Ages made of them later. -

Starak Collection Vol. 1

Starak Collection Vol. 1 004 005 ROZMOWA Z ANNĄ I JERZYM STARAKAMI, Interview with Anna and Jerzy Starak, KOLEKCJONERAMI, FUNDATORAMI FUNDACJI collectors, founders of the Starak RODZINY STARAKÓW ORAZ Z ELŻBIETĄ Family Foundation and with Elżbieta DZIKOWSKĄ, PREZES FUNDACJI RODZINY Dzikowska, president of the Starak STARAKÓW Family Foundation – Rozmawiamy w budynku Spectra. To starannie przemyślany, – We are having this conversation in the Spectra building, which imponujący biurowiec, dostrzeżona przez znawców perełka is a carefully considered and impressive office building, an archi- architektoniczna. Dla Pana to ważne miejsce, które skupia jak tectural gem acknowledged by experts. For you it is an important w soczewce Pana dokonania, sukcesy i wybory, nie tylko bizne- place, which, like a lens, concentrates your achievements, suc- sowe. Co zadecydowało o umieszczeniu w tym miejscu części cesses and choices, not only the business ones. What was the Państwa prywatnej kolekcji? deciding factor in placing here a part of your private collection? Jerzy Starak: Przede wszystkim chciałem podzielić się moją Jerzy Starak: First and foremost, I was eager to share my kolekcją z ludźmi, z którymi na co dzień współpracuję, moimi collection with people with whom I work on a daily basis, my pracownikami, klientami biznesowymi. Mam świadomość, jak employees and business clients. I am aware of how essential it ważne dla każdego człowieka jest zachowanie równowagi is for everyone to maintain the work-life balance. Locating the między życiem osobistym i zawodowym. Umieszczenie kolekcji collection in this place creates friendly working conditions and, w tym właśnie miejscu stwarza przyjazne warunki pracy i oprócz apart from the traditional professional development, it stimulates tradycyjnego rozwoju zawodowego, pobudza kreatywność. -

A Farewell to Giedroyc

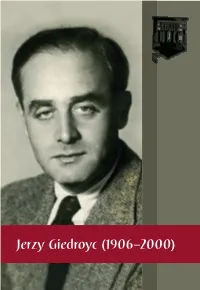

Warsaw, January 2017 A farewell to Giedroyc Katarzyna Pełczyńska-Nałęcz The plans for the future of TV Belsat presented by Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski are a good excuse for an overall reflection on Poland’s eastern policy as it is being conducted today. The proposal to drastically reduce Belsat’s funding and pass those savings on to funds for a new Polish-language channel to be broadcast abroad, including officially to Belarus, should not be seen as a one-off deci- sion. It is a symptom of a fundamental turn-around: the departure from the assumptions that have guided nearly 25 years of Poland’s policy towards its Eastern European neighbours. Symbolically, this change can be described as ‘a farewell to Giedroyc’. No free Poland without a free Ukraine Despite various twists and turns, the Third Republic’s eastern policy has constantly drawn on several fundamental principles1. The roots of these principles lay in the concept, formulated in the 1960s by Mieroszewski and Giedroyc, of how to approach Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus (ULB for short), which were then parts of the USSR2. These principles can be summarised as follows: Poland’s freedom is closely linked to the sovereignty (de facto independence from Russia) of our eastern neighbours. If Stefan Batory Foundation 1 In Polish historiography, periods of the statehood of the Republic of Poland (Pol. Rzeczpospolita Polska) are un- officially numbered as follows: the First Republic (Pol.I. Rzeczpospolita, from the mid-15th century until the final partition of 1795), the Second Republic (Pol. II. Rzeczpospolita, 1918–1945) and the Third Republic (Pol. -

Parisian Culture's Views on Eastern Europe As a Factor

POLISH POLITICAL SCIENCE VOL XXXIV 2005 PL ISSN 0208-7375 ISBN 83-7322-481-5 PARISIAN CULTURE’S VIEWS ON EASTERN EUROPE AS A FACTOR IN CONTEMPORARY POLISH FOREIGN POLICY by Iwona Hofman When analyzing events which unfolded in the Ukraine during the fi nal months of 2004 and the involvement of Polish politicians and public opinion in the strug- gle for the preservation of the democratic character of presidential elections, a question arises regarding the connection of their actions with the political projects of Jerzy Giedroyć, the founder and sole editor of an infl uential magazine and a centre of political thought, which was Culture , published in Maisons-Laffi tte, near Paris, in the years 1947–2000. Historians and political scientists rightly emphasize the fact that the „Eastern doctrine”, also known as the ULB doctrine (from the abbreviation of „Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus”), has been a constant element of Polish foreign policy since 1989. Generally speaking, Giedroyć was convinced that nationalist impulses would eventually destroy the Russian empire from within, and a sovereign Poland would gain three new neighbours in the East: Ukraine, Lithu- ania and Belarus. " is process was expected to take place in the near future, as foreseen by Culture contributors who called on the émigrés from Eastern Europe to work together in laying solid foundations for the future partnership. Restricted in his political activities, Jerzy Giedroyć believed that words could be translated into actions. He also realized that a magazine whose program is characterized by far-reaching visions based on dismantling the European order shaped in Yalta, must fi rst of all fi ght national prejudices and stereotypes, present true history and show the common fate of the then enslaved nations. -

Digitization of the Resources of the Literary Institute in Paris

Artykuły Kognitywistyka i Media w Edukacji 2018, nr 2 Ewelina Górka Digitization of the resources of the Literary Institute in Paris Abstrakt Digitalizacja zasobów Instytutu Literackiego w Paryżu Instytut Literacki został założony w 1946 r. w Rzymie. Jak wskazano w powołują- cym go rozkazie, głównym celem było prowadzenie akcji wydawniczej w dziedzinie kulturalnej, literackiej i społecznej, a także zbieranie dorobku piśmiennictwa pol- skiego. Inicjatorem tego przedsięwzięcia i redaktorem był Jerzy Giedroyc. W okre- sie funkcjonowania Instytutu Literackiego, tj. w latach 1947–2000, ukazało się 637 numerów miesięcznika „Kultura”, 171 numerów kwartalnika „Zeszyty Historyczne” oraz książki: 26 publikacji w latach 1947–1952 i 378 książek w serii „Biblioteka Kul- tury”. Oprócz wskazanych wyżej publikacji, w archiwum Instytutu Literackiego za- chowała się bardzo duża liczba innych książek, czasopism polskich i zagranicznych, wycinków prasowych oraz dokumentów, listów i fotografii. Ich zebranie i uporząd- kowanie, a także wykonanie wersji elektronicznej było możliwe m.in. dzięki projek- tom: „Inwentarz Archiwum Instytutu Literackiego Kultura” oraz „Digitalizacja Ar- chiwum Instytutu Literackiego”. W artykule została zwrócona uwaga na proces digitalizacji zasobów Instytutu Lite- rackiego. Cyfrowe wersje oryginalnych tekstów źródłowych mogą bowiem posłu- żyć dalszym badaniom na temat spuścizny Jerzego Giedroycia. Wskazany dostęp to także ułatwienie do podejmowania dalszych prac i ochrona dokumentów, zwłasz- cza rękopisów, w związku z niszczeniem i upływem czasu. Jako przykład ilustrują- cy tę tezę w artykule posłużono się przykładem Jerzego Pomianowskiego, jedne- go ze współpracowników paryskiej „Kultury”, wskazując sposoby przeprowadzania wstępnej kwerendy źródłowej, tak ważnej dla realizacji tematu badawczego. Słowa kluczowe: Instytut Literacki, Jerzy Giedroyc, digitalizacja Digitization of the resources of the Literary Institute in Paris 151 The Literary Institute was founded in 1946 in Rome. -

Univerzita Pardubice Fakulta Filozofická Kapisté. Polští Malíři Působící V Paříži Dvacátých Let 20. Století Bc. K

Univerzita Pardubice Fakulta filozofická Kapisté. Polští malíři působící v Paříži dvacátých let 20. století Bc. Kristýna Mertová Diplomová práce 2016 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámen s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Tallinnu dne 23. 6. 2016 Kristýna Mertová ANOTACE Komitet Paryski byl volným uskupením třinácti mladých polských umělců, kteří se pod vlivem profesora a malíře Józefa Pankiewicze vydali do Paříže roku 1924. Zde několik let studovali jak klasická, tak moderní malířství, které posléze přetvářeli v originální díla s vlastním rukopisem. Diplomová práce se zabývá celou skupinou i styly jednostlivých členů, inspirací, kterou během pobytu čerpali a nastiňuje jejich budoucí úspěch v malířské profesi. KLÍČOVÁ SLOVA Komitet Paryski, kapisté, Polsko, Paříž TITLE Kapists. Polish painters active in Paris in the 1920´s. ANNOTATION The Paris Committee was a group of thirteen polish painters, who went to Paris under influence of their professor Józef Pankiewicz in 1924. There they were studying classic and modern paintings which transformed into own original canvas. -

Speakers and Chairpersons

Speakers and Chairpersons Professor Urszula Augustyniak (born 1950) gained her Master’s, Doctoral and Habilitation degrees at the University of Warsaw in 1973, 1979 and 1988 respectively. She has taught at the Institute of History at the University of Warsaw since 1977, and has served inter alia as Pro-Dean and head of the Early Modern History section of the Institute of History, as well as head of the Lithuanistica Commission of the Polish Academy of Sciences. A specialist on the cultural, social, political and confessional history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, among her more recent publications are Wazowie i ‘królowie rodacy’. Studium władzy królewskiej w Rzeczypospolitej XVII wieku (1999), two monographs on Hetman Krzysztof II Radziwiłł (2001), Historia Polski 1572-1795 (2008, also published as History of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: State – Society – Culture, 2015) and Państwo świeckie czy księże? Spór o rolę duchowieństwa katolickiego w Rzeczypospolitej w czasach Zygmunta III Wazy. Wybór tekstów (2012). Katarzyna Błachowska is a habilitated doctor of the Institute of History of the University of Warsaw, where she heads the Didactic and Historiographical Section. Since 2002 she has been a member of the Polish-Ukrainian group ‘The Multicultural Historical Environment of Lwów/Lviv in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century’. Her research interests cover Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian historiography in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the history of Rus’ and the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Among her more important publications are (as Katarzyna Krupa) articles on the links of Lithuanian dukes with Novgorod the Great in the fifteenth century (published in Kwartalnik Historyczny and Przegląd Historyczny in 1993) and (as Katarzyna Błachowska) the books Emergence of the Empire. -

Polacy W Gruzji Poles in Georgia

Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych The Head Office of the State Archives Narodowe Archiwum Gruzji The National Archives of Georgia Stowarzyszenie „Wspólnota Polska” Association “Polish Community” Archiwum Państwowe m.st. Warszawy The State Archive of the Capital City of Warsaw POLACY W GRUZJI POLES IN GEORGIA Tbilisi, fot. Magda Będzińska, 2009 r. Tbilisi, photographs by Magda Będzińska, 2009. W archiwach gruzińskich zachowało się wiele inte - W Archiwum Narodowym Gruzji przechowywa - Celem wystawy jest przedstawienie Polaków miesz - resujących dokumentów na temat Polaków żyjących nych jest ponad 200 dokumentów odzwierciedlających kających w Gruzji w XIX i na początku XX wieku, ich na Kaukazie w XIX i na początku XX wieku. przyjacielskie stosunki między narodem polskim i gru - wkładu w rozwój gospodarczy i kulturalny kraju oraz W ostatnich latach polskie i gruzińskie archiwa na - zińskim. działalności polskich organizacji społeczno-kultural - wiązały ożywioną współpracę. Jesienią 2008 r. w uro - nych (Towarzystwo Dobroczynności i „Dom Polski”). czystych obchodach 200-lecia Archiwum Głównego W Oddziale Akt Dawnych Centralnego Archiwum Histo - W prezentowanej ekspozycji odnajdą Państwo wybit - Akt Dawnych uczestniczyła dyrektor Archiwum rycznego Gruzji przechowywany jest zespół Katolikosa nych architektów, artystów i przyrodników. Obok Narodowego Gruzji Teona Iaszwili. W 2009 r. z wi - Gruzji Kiriona II (1917-1918), zawierający rozmaite doku - nich pokazujemy materiały dotyczące osób mniej zna - zytą oficjalną w Gruzji przebywała zastępca Na - menty, w tym także sporządzone w języku polskim. nych – nauczycieli, lekarzy, rzemieślników. czelnego Dyrektora Archiwów Państwowych Barbara Berska i dyrektor Archiwum Państwo - Dokumenty XX-wieczne zawierają informacje Prezentowane na wystawie materiały archiwalne po - wego m.st. Warszawy Ryszard Wojtkowski. Wtedy o dniach kultury polskiej w Gruzji i kultury gruzińskiej chodzą z zasobu Archiwum Narodowego Gruzji i Gru - też zrodził się pomysł zorganizowania wystawy w Polsce. -

Jerzy Giedroyc (1906–2000)

Jerzy Giedroyc (1906–2000) Jerzy Giedroyc, Maisons-Laffitte, 1987 r. r. 1987 Maisons-Laffitte, Giedroyc, Jerzy Fot. © BohdanPaczowski Redaktor. Tak mówiono i pisano o Jerzym Giedroyciu naj- częściej. Był znany jako twórca i redaktor wydawanego od 1947 r. miesięcznika „Kultura” oraz założyciel Instytutu Li- terackiego. Podparyskie Maisons-Laffitte, gdzie mieściła się siedziba zarówno redakcji, jak i Instytutu, stało się symbolem polskiej kultury na emigracji po II wojnie światowej. To tu wy- chodziły nie tylko przekłady na język polski Geor ge’a Orwella Rczy Arthura Koestlera, lecz też dzieła Gustawa Herlinga-Gru- dzińskiego, Witolda Gombrowicza, Czesława Miłosza i wielu innych pisarzy, które nie mogły ukazać się drukiem w kraju po 1945 r. Bez Redaktora – często pisanego właśnie wielką literą – polska kultura byłaby prawdopodobnie uboższa o te i o wiele innych nazwisk. Jerzy Giedroyc to jednak nie tylko wydawca, lecz także ktoś, kto inspirował, przekonywał do spraw beznadziejnych, załatwiał rzeczy niemożliwe do załatwienia, zmieniał przeko- nania Polaków, a czasem również – ich sąsiadów. Książę Jerzy Giedroyc urodził się 27 lipca 1906 r. w Mińsku Li- tewskim. Był pierwszym z trzech synów aptekarza Ignacego Giedroycia i Franciszki ze Starzyckich. Jako dziesięciolatek został wysłany przez rodziców do gimnazjum w Moskwie. To miasto mogło się wydawać wtedy miejscem bezpiecz- niejszym niż Mińsk, bo położonym dalej od frontu. Nikt nie przypuszczał jednak, że już niedługo stolica Rosji pogrąży Jsię w chaosie rewolucji. Zanim to się stało, młody Giedroyc mieszkał na stancji i uczył się w gimnazjum Komitetu Pol- skiego. W 1917 r., kiedy skończył się rok szkolny, wyruszył do Petersburga, gdzie miał nadzieję spotkać swojego stry- ja. -

(1946-2000) (Association Institut Littéraire "Kultura") (Poland) Ref N° 2008-54

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Archives of the Literary Institute in PARIS (1946-2000) (Association Institut Littéraire "Kultura") (Poland) Ref N° 2008-54 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY ARCHIVES of THE LITERARY INSITUTE in PARIS (1946-2000) (Association Institut Littéraire “Kultura”) The Archives of the Literary Institute are the complete documentation of the Institute’s activities in the years 1946-2000. They are a unique collection, which depicts the work of an unparalleled emigration institution, which, thanks to the intellectual and political vision implemented for decades by its founders and leaders, played an extremely vital role in one of the most important historical events of the 20th century – the peaceful victory over the communist dictatorship and the division of the world into two hostile political blocs. The Institute significantly contributed to the success of the transformation of 1989-1990s by creating intellectual and political foundations, which, through a dialogue of the elites, allowed for reconciliation between the nations of Eastern and Central-Eastern Europe. The Institute also deserves recognition because it enabled the intellectuals of this part of Europe to participate in a wide international intellectual exchange in a period of an information blockade and censorship that lasted till the end of the 1980s. The Institute fulfilled the functions of: • the publishing house that produced the journal “Kultura” that inspired intellectuals from Central-Eastern Europe and fought against censorship in the countries under totalitarian rule, • a centre of independent political thought for emigrants from Eastern European countries, such as Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Baltic countries, • an organizer of support for authors, dissidents and independent organizations from countries behind the Iron Curtain in the 1950s and 1960s, especially for organizations that were established in the 1970s, like e.g. -

Dorota Sieroń-Galusek, Józef Czapski – About Learning and Teaching Art

RIHA Journal 0030 | 20 October 2011 Józef Czapski – about learning and teaching art Dorota Sieroń-Galusek Peer review and editing organized by" Międzynarodowe Centrum ultury, ra"#w / International Cultural Centre, rakow #evie ers" Maria Hussa"owska&'zy%zko, Janusz (ezda Polish version available at / Wersja polska dostępna pod: (RIHA Journal 0029) Abstract The subject of the article is the issues of intellectual and artistic formation. From the extremely rich life and intellectual background of Józef Czapski (1896–1993) – a painter and writer – the author selects the experiences he gained as a co-creator of the Kapiści group, that is a company of students who organised a trip to Paris under the supervision of Professor Józef Pankiewicz and was later transformed into a self-teaching group. Pankiewicz himself subsequently became an important figure for Czapski. Walks in the Louvre organised by Pankiewicz, not only for his students, were recorded by Czapski in a long interview published as a book. There is a likely connection between the Paris experience of the young painter and the situation when years later an émigré to Paris Józef Czapski introduced others into the world of painting, both through his essays and during walks modelled on those that Pankiewicz had invited him to. And it is this moment determining the fact that a student, consciously looking at his master, in his turn becomes a master for others, that forms the subject of these reflections. 3 4 Józef Czapski ( !"#$ ""%& $ a painter+ essayist and abo-e all a man 'hose almost century(long life 'as marked 'ith epoch(making experiences.