A Structural Assessment of the U.S. Counterespionage Vis-Ŕ-Vis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinabrief in a Fortnight

ChinaBrief Volume XIV s Issue 21 s November 7, 2014 VOLUME XIV s ISSUE 21 s NOVEMBER 7, 2014 In This Issue: IN A FORTNIGHT By Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga 1 CHINA’S ESPIONAGE AGAINST TAIWAN (PART I): ANALYSIS OF RECENT OPERATIONS By Peter Mattis 4 Chinese and Indian troops conduct a joint counter- REGIONAL MANEUVERING PRECEDES OBAMA-XI MEETING AT APEC SUMMIT terrorism exercise in 2008. By Richard Weitz 8 (Credit: Xinhua) A FAMILY DIVIDED: THE CCP’S CENTRAL ETHNIC WORK CONFERENCE By James Leibold 12 China Brief is a bi-weekly jour- SINO-INDIAN JOINT MILITARY EXERCISES: OUT OF STEP nal of information and analysis covering Greater China in Eur- By Sudha Ramachandran 16 asia. China Brief is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation, a private non-profit organization In a Fortnight based in Washington D.C. and is edited by Nathan Beauchamp- CHINA CYNICAL OVER U.S. MIDTERM ELECTIONS, BUT EXPECTS Mustafaga. POLICY CONTINUITY The opinions expressed in By Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga China Brief are solely those of the authors, and do not n Tuesday, November 4, the United States held its 2014 midterm elections necessarily reflect the views of The Jamestown Foundation. Oand voted the Republican Party into the majority in the U.S. Senate, giving them control of both houses in Congress and, as Chinese analysts noted, a major political victory. The overall Chinese response was cynical about the lack of real democracy in the elections and dismissive of U.S. President Barack Obama’s influence in the last two years of his presidency. Despite some concerns for U.S.- China relations with a more hawkish Republican Congress, Chinese commentators remain optimistic about the future of the bilateral relationship and look forward For comments and questions about China Brief, please con- to President Obama’s visit to Beijing for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation tact us at Summit (APEC) later this month (see “Regional Maneuvering” in this issue). -

CI TRENDS CI Trends: Espionage Related 1 Activity in Southern California Espionage Related Activity in Southern California, Part 2

COUNTERINTELLIGENCE AND CYBER NEWS AND VIEWS Corporate Headquarters 222 North Sepulveda Boulevard, Suite 1780 El Segundo, California 90245 (310) 536-9876 www.advantagesci.com COUNTERINTELLIGENCE AND CYBER NEWS AND VIEWS MARCH 2012 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Inside this Issue CI TRENDS CI Trends: Espionage Related 1 Activity in Southern California Espionage Related Activity in Southern California, Part 2 Suspect Counterfeit Electronic 2 In last month’s newsletter, we had only illustrative of one of the oldest techniques Parts Can Be Found on scraped the surface of espionage and used in espionage. The fine art of Front Companies: Who Is the 7 End User? national security related crimes occurring seduction has been used throughout DARPA’s Shredder Challenge 9 within the Los Angeles area. As one of the history to obtain classified information purposes of this newsletter includes serving from males and females. In the cases of Threats To Nanotechnology 10 as an educational tool, the use of actual Data Exfiltration and Output 11 Richard Miller and J.J. Smith, both were Devices - An Overlooked cases to illustrate how espionage has seduced, and then they betrayed the How spies used Facebook to 14 occurred in the past serves to meet this confidences placed in them by the U.S. steal Nato chiefs’ details purpose. Government. Extracts from Wikipedia pertaining to Miller and Smith (not a Retired agent suspected of 16 Everyone likes to hear “spy stories”, except Espionage spying for China: definitive source, but very illustrative for when they hit closest to home. Then the these two cases) follow: ARRESTS, TRIALS, 17 stories are not so fun to hear. -

Asian Americans: Collateral Damage in the New Cold War with China? Increasingly, the Media Has Reported on Warnings by Top U.S

NAPABA Conference - Chicago November 10, 2018 Moderator: Asian Aryani Ong Americans: Panelists: Collateral Mara Hvistendahl Damage in the Andrew Kim new Cold War Patrick Toomey with China? Sean Vitka Chinese American Scientists, Not Spies Dr. Wen Ho Lee Guoqing Cao (left front), Xiaorong Wang (left back), Sherry Chen (middle), Shuyi Li (right front), Xiaoxing Xi (right back) U.S. views on Chinese intelligence Thousand Grains of Sand Distributed View Multiple Chinese China targets government agencies, Chinese Americans actors. Independent actors incentivized by financial gain. 1990’s Present Day CLE Materials Compiled by Mara Hvistendahl . Changing views of Chinese intelligence . Paul Moore, “Chinese Culture and the Practice of ‘Actuarial’ Intelligence,” conference presentation from 1996 . Peter Mattis, “Beyond Spy vs. Spy: The Analytical Challenge of Understanding Chinese Intelligence Services,” Studies in Intelligence Vol. 56, No. 3 (September 2012) Economic Espionage Act cases,1996-2015 Study by Andrew Kim Published by Committee of 100 • # of EEA defendants with Chinese names tripled between 2009-2015, from 1996 to 2008 • 50% of EEA cases alleged theft of secrets for a US entity, 33% for China, none for Russia • Convicted defendants of Asian heritage received sentences twice as severe • 1 in 5 accused ”spies” of Asian heritage may be innocent CLE Materials Compiled by Andrew Kim . Prosecuting Chinese “Spies:” An Empirical Analysis of the Economic Espionage Act, Executive Summary Presented by Committee of 100, May 17, 2018, Washington, D.C. Authored by Andrew Kim . Economic Espionage and Trade Secrets: Asian Americans in the Crosshairs – Power point Presentation by Andrew Kim Xiaoxing Xi et al. v. United States et al. -

China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S

Order Code RL30143 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Updated February 1, 2006 Shirley A. Kan Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Summary This CRS Report discusses China’s suspected acquisition of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets, including that on the W88, the newest U.S. nuclear warhead. This serious controversy became public in early 1999 and raised policy issues about whether U.S. security was further threatened by China’s suspected use of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets in its development of nuclear forces, as well as whether the Administration’s response to the security problems was effective or mishandled and whether it fairly used or abused its investigative and prosecuting authority. The Clinton Administration acknowledged that improved security was needed at the weapons labs but said that it took actions in response to indications in 1995 that China may have obtained U.S. nuclear weapon secrets. Critics in Congress and elsewhere argued that the Administration was slow to respond to security concerns, mishandled the too narrow investigation, downplayed information potentially unfavorable to China and the labs, and failed to notify Congress fully. On April 7, 1999, President Clinton gave his assurance that partly “because of our engagement, China has, at best, only marginally increased its deployed nuclear threat in the last 15 years” and that the strategic balance with China “remains overwhelmingly in our favor.” On April 21, 1999, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) George Tenet, reported the Intelligence Community’s damage assessment. -

Preventing Loss of Academic Research

COUNTERINTELLIGENCE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP FBI INTELLIGENCE NOTE (S PIN) SPIN - 15- 006 J U N E 2 0 1 5 Preventing Loss of Academic Research INTRODUCTION US Colleges and Universities are known for innovation, collaboration, and knowledge-sharing. These qualities help form the bedrock of US economic success. These same qualities also make US universities prime targets for theft of patents, trade secrets, Intellectual Property (IP), research, and sensitive information. Theft of patents, designs and proprietary informa- tion have resulted in the bankruptcy of US businesses and loss of research funding to US universities in the past. When a foreign company uses stolen data to create products, at a reduced cost, then compete against American products, this can have direct harmful conse- quences for US universities that might receive revenue through patents and technology trans- fer. Foreign adversaries and economic competitors can take advantage of the openness and col- laborative atmosphere that exists at most learning institutions in order to gain an economic and/or technical edge through espionage. Espionage tradecraft is the methodology of gathering or acquiring such information. Most foreign students, professors, researchers, and dual-nationality citizens studying or working in the United States are in the US for legitimate reasons. Very few of them are actively working at the behest of another government or competing organiza- tion. However, some foreign governments pressure legitimate students and expatriates to report valuable information to intel- ligence officials, often using the promise of favors or threats to family members back home. The goal of this SPIN is to provide an overview of the threats economic espionage poses to the academic and business com- munities. -

Pluralist Universalism

Pluralist Universalism Pluralist Universalism An Asian Americanist Critique of U.S. and Chinese Multiculturalisms WEN JIN The Ohio State University Press | Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jin, Wen, 1977– Pluralist universalism : an Asian Americanist critique of U.S. and Chinese multiculturalisms / Wen Jin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1187-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9288-4 (cd) 1. Multiculturalism in literature. 2. Cultural pluralism in literature. 3. Ethnic relations in literature. 4. Cultural pluralism—China. 5. Cultural pluralism—United States. 6. Multicul- turalism—China. 7. Multiculturalism—United States. 8. China—Ethnic relations. 9. United States—Ethnic relations. 10. Kuo, Alexander—Criticism and interpretation. 11. Zhang, Chengzhi, 1948—Criticism and interpretation. 12. Alameddine, Rabih—Criticism and inter- pretation. 13. Yan, Geling—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PN56.M8J56 2012 810.9'8951073—dc23 2011044160 Cover design by Mia Risberg Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Mate- rials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Jin Yiyu Zhou Huizhu With love and gratitude CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Bridging the Chasm: A Survey -

William "Bill" Cleveland Jr., (Accessed Jan

1/7/2021 "parlor Maid" - Chronology | From China With Love | FRONTLINE | PBS WATCH SCHEDULE TOPICS ABOUT FRONTLINE SHOP TEACHER CENTER SUPPORT PROVIDED BY [ William "Bill" Cleveland Jr., (Accessed Jan. 07, 2012). From China With Love, Chronology of FBI-Chinese double agent Katrina Leung aka "Parlor Maid." PBS WOSU Frontline. ] A chronological outline of the "Parlor Maid" story, drawn from the government's court filings in the cases against Katrina Leung] and J.J. Smith. 1969 Bill Cleveland begins working for the FBI In the early 1970s, Cleveland, the son of an assistant director of the FBI, begins working in the FBI's San Francisco office. He eventually becomes the San Francisco office's supervisory special agent for Chinese counterintelligence. RECENT STORIES November 18, 2015 / 5:27 October 1970 J.J. Smith begins working for the FBI pm In Fight Against He begins his career in the FBI's Salt Lake City office and is transferred to the Los Angeles office one year later. ISIS, a Lose-Lose In October 1978, J.J. is assigned to the foreign counterintelligence squad focused on the People's Republic of China. He remains in the Los Angeles office and works Chinese counterintelligence until his retirement in Scenario Poses November 2000. Challenge for West November 17, 2015 / 6:13 Late 1970s Katrina Leung is contacted by the FBI pm According to sources close to Katrina, she is first recruited by the FBI while living in ISIS is in Chicago, where she was obtaining an MBA at the University of Chicago. Afghanistan, But Who Are They Really? November 17, 2015 / 1:59 pm 1979 "Tiger Trap" investigation begins “The Most Risky … Job Ever.” A source in China allegedly provides the U.S. -

Advanced Technology Acquisition Strategies of the People's Republic

Advanced Technology Acquisition Strategies of the People’s Republic of China Principal Author Dallas Boyd Science Applications International Corporation Contributing Authors Jeffrey G. Lewis and Joshua H. Pollack Science Applications International Corporation September 2010 This report is the product of a collaboration between the Defense Threat Reduction Agency’s Advanced Systems and Concepts Office and Science Applications International Corporation. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Report Number ASCO 2010-021 Contract Number DTRA01-03-D-0017, T.I. 18-09-03 The mission of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) is to safeguard America and its allies from weapons of mass destruction (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high explosives) by providing capabilities to reduce, eliminate, counter the threat, and mitigate its effects. The Advanced Systems and Concepts Office (ASCO) supports this mission by providing long-term rolling horizon perspectives to help DTRA leadership identify, plan, and persuasively communicate what is needed in the near-term to achieve the longer-term goals inherent in the Agency’s mission. ASCO also emphasizes the identification, integration, and further development of leading strategic thinking and analysis on the most intractable problems related to combating weapons of mass destruction. For further information on this project, or on ASCO’s broader research program, please contact: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office 8725 John J. -

Fbi Tampa Ci Strategic Partnership Newsletter

FBI TAMPA CI STRATEGIC PARTN ERSHIP NEWSLETTER June 1, 2011 Volume 3 Issue 6 Federal Bureau of Investigation 11000 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 1700 Los Angeles, California 90024, 310.477.6565 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: NOTE: In 2 COUNTERINTELLIGENCE TRENDS accordance with Title 17 2 The Insider Threat; Safeguarding Trade Secrets Proprietary Information and U.S.C. Section Research 107, this material is distributed 12 ARRESTS, TRIALS AND CONVICTIONS without profit 12 China's spying seeks secret US info or payment for 19 Sailor pleads guilty to espionage charges in Norfolk non-profit news reporting 21 Former L-3 Worker Indicted For Data Breach and 22 THREE INDIVIDUALS AND TWO COMPANIES INDICTED FOR CONSPIRING TO educational EXPORT MILLIONS OF DOLLARS WORTH OF COMPUTER-RELATED EQUIPMENT TO purposes only. IRAN Use does not reflect official 25 Broomfield man charged with giving defense data to South Korea endorsement 26 California man gets 25 years for missile-smuggling plot by the FBI. 27 Fired Gucci Network Engineer Charged for Taking Revenge on Company Reproduction for private use 28 Belgians charged with smuggling aircraft parts or gain is subject 29 TECHNIQUES, METHODS, TARGETS to original copyright 29 How a networking immigrant became a spy restrictions. 35 Shriver Case Highlights Traditional Chinese Espionage Individuals 42 Condé Nast got hooked by $8 million spear-phishing scam interested in 44 Exclusive: Inside Area 51, the Secret Birthplace of the U2 Spy Plane subscribing to this 47 Helping an Attorney Prove an Employee Theft/Theft of Trade -

Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: Chinese Human Intelligence Operations Against the United States

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: Chinese Human Intelligence Operations against the United States Peter Mattis Fellow, The Jamestown Foundation June 9, 2016 China’s intelligence services are among the world’s most active against the United States, but the Chinese approach to human intelligence (HUMINT) remains misunderstood. Observers have conflated the operations of the intelligence services with the amateur clandestine collectors (but professional scientists/engineers/businesspeople) who collect foreign science and technology. The Chinese intelligence services have a long professional history, dating nearly to the dawn of the Chinese Communist Party, and intelligence has long been the province of professionals. The intelligence services were not immune to the political purges and the red vs. expert debates, and the Cultural Revolution destroyed much of the expertise in clandestine agent operations.1 As China’s interests abroad have grown and the blind spots created by the country’s domestic-based intelligence posture have become more acute, the Chinese intelligence services are evolving operationally and becoming more aggressive in pursuit of higher-quality intelligence. * * * The principal intelligence services conducting HUMINT operations, both clandestine and overt, against the United States are the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and Joint Staff Department’s Intelligence Bureau (JSD/IB) in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Prior to the military reforms announced in November 2015, the latter was known as the General Staff Department’s Second Department (commonly abbreviated 2PLA). Because the full ramifications of the PLA’s reform effort have unclear implications for intelligence, the testimony below will reflect what was known about 2PLA rather than the JSD/IB, unless specifically noted. -

Scholars Or Spies: Foreign Plots Targeting America's Research and Development

SCHOLARS OR SPIES: FOREIGN PLOTS TARGETING AMERICA’S RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT & SUBCOMMITTEE ON RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 11, 2018 Serial No. 115–54 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 29–781PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HON. LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas DANA ROHRABACHER, California ZOE LOFGREN, California MO BROOKS, Alabama DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois SUZANNE BONAMICI, Oregon BILL POSEY, Florida AMI BERA, California THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ELIZABETH H. ESTY, Connecticut JIM BRIDENSTINE, Oklahoma MARC A. VEASEY, Texas RANDY K. WEBER, Texas DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Virginia STEPHEN KNIGHT, California JACKY ROSEN, Nevada BRIAN BABIN, Texas JERRY MCNERNEY, California BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia PAUL TONKO, New York RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, Louisiana BILL FOSTER, Illinois DANIEL WEBSTER, Florida MARK TAKANO, California JIM BANKS, Indiana COLLEEN HANABUSA, Hawaii ANDY BIGGS, Arizona CHARLIE CRIST, Florida ROGER W. MARSHALL, Kansas NEAL P. DUNN, Florida CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, LOUISIANA, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma DONALD S. BEYER, Jr., Virginia BILL POSEY, Florida JERRY MCNERNEY, California THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas ROGER W. MARSHALL, Kansas CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas SUBCOMMITTEE ON RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY HON. -

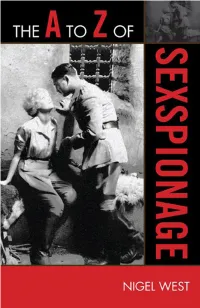

Nigel West, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19.