Unconventional Spies: the Counterintelligence Threat from Non-State Actors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CI TRENDS CI Trends: Espionage Related 1 Activity in Southern California Espionage Related Activity in Southern California, Part 2

COUNTERINTELLIGENCE AND CYBER NEWS AND VIEWS Corporate Headquarters 222 North Sepulveda Boulevard, Suite 1780 El Segundo, California 90245 (310) 536-9876 www.advantagesci.com COUNTERINTELLIGENCE AND CYBER NEWS AND VIEWS MARCH 2012 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Inside this Issue CI TRENDS CI Trends: Espionage Related 1 Activity in Southern California Espionage Related Activity in Southern California, Part 2 Suspect Counterfeit Electronic 2 In last month’s newsletter, we had only illustrative of one of the oldest techniques Parts Can Be Found on scraped the surface of espionage and used in espionage. The fine art of Front Companies: Who Is the 7 End User? national security related crimes occurring seduction has been used throughout DARPA’s Shredder Challenge 9 within the Los Angeles area. As one of the history to obtain classified information purposes of this newsletter includes serving from males and females. In the cases of Threats To Nanotechnology 10 as an educational tool, the use of actual Data Exfiltration and Output 11 Richard Miller and J.J. Smith, both were Devices - An Overlooked cases to illustrate how espionage has seduced, and then they betrayed the How spies used Facebook to 14 occurred in the past serves to meet this confidences placed in them by the U.S. steal Nato chiefs’ details purpose. Government. Extracts from Wikipedia pertaining to Miller and Smith (not a Retired agent suspected of 16 Everyone likes to hear “spy stories”, except Espionage spying for China: definitive source, but very illustrative for when they hit closest to home. Then the these two cases) follow: ARRESTS, TRIALS, 17 stories are not so fun to hear. -

China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S

Order Code RL30143 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Updated February 1, 2006 Shirley A. Kan Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Summary This CRS Report discusses China’s suspected acquisition of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets, including that on the W88, the newest U.S. nuclear warhead. This serious controversy became public in early 1999 and raised policy issues about whether U.S. security was further threatened by China’s suspected use of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets in its development of nuclear forces, as well as whether the Administration’s response to the security problems was effective or mishandled and whether it fairly used or abused its investigative and prosecuting authority. The Clinton Administration acknowledged that improved security was needed at the weapons labs but said that it took actions in response to indications in 1995 that China may have obtained U.S. nuclear weapon secrets. Critics in Congress and elsewhere argued that the Administration was slow to respond to security concerns, mishandled the too narrow investigation, downplayed information potentially unfavorable to China and the labs, and failed to notify Congress fully. On April 7, 1999, President Clinton gave his assurance that partly “because of our engagement, China has, at best, only marginally increased its deployed nuclear threat in the last 15 years” and that the strategic balance with China “remains overwhelmingly in our favor.” On April 21, 1999, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) George Tenet, reported the Intelligence Community’s damage assessment. -

Pluralist Universalism

Pluralist Universalism Pluralist Universalism An Asian Americanist Critique of U.S. and Chinese Multiculturalisms WEN JIN The Ohio State University Press | Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jin, Wen, 1977– Pluralist universalism : an Asian Americanist critique of U.S. and Chinese multiculturalisms / Wen Jin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1187-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9288-4 (cd) 1. Multiculturalism in literature. 2. Cultural pluralism in literature. 3. Ethnic relations in literature. 4. Cultural pluralism—China. 5. Cultural pluralism—United States. 6. Multicul- turalism—China. 7. Multiculturalism—United States. 8. China—Ethnic relations. 9. United States—Ethnic relations. 10. Kuo, Alexander—Criticism and interpretation. 11. Zhang, Chengzhi, 1948—Criticism and interpretation. 12. Alameddine, Rabih—Criticism and inter- pretation. 13. Yan, Geling—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PN56.M8J56 2012 810.9'8951073—dc23 2011044160 Cover design by Mia Risberg Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Mate- rials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Jin Yiyu Zhou Huizhu With love and gratitude CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Bridging the Chasm: A Survey -

William "Bill" Cleveland Jr., (Accessed Jan

1/7/2021 "parlor Maid" - Chronology | From China With Love | FRONTLINE | PBS WATCH SCHEDULE TOPICS ABOUT FRONTLINE SHOP TEACHER CENTER SUPPORT PROVIDED BY [ William "Bill" Cleveland Jr., (Accessed Jan. 07, 2012). From China With Love, Chronology of FBI-Chinese double agent Katrina Leung aka "Parlor Maid." PBS WOSU Frontline. ] A chronological outline of the "Parlor Maid" story, drawn from the government's court filings in the cases against Katrina Leung] and J.J. Smith. 1969 Bill Cleveland begins working for the FBI In the early 1970s, Cleveland, the son of an assistant director of the FBI, begins working in the FBI's San Francisco office. He eventually becomes the San Francisco office's supervisory special agent for Chinese counterintelligence. RECENT STORIES November 18, 2015 / 5:27 October 1970 J.J. Smith begins working for the FBI pm In Fight Against He begins his career in the FBI's Salt Lake City office and is transferred to the Los Angeles office one year later. ISIS, a Lose-Lose In October 1978, J.J. is assigned to the foreign counterintelligence squad focused on the People's Republic of China. He remains in the Los Angeles office and works Chinese counterintelligence until his retirement in Scenario Poses November 2000. Challenge for West November 17, 2015 / 6:13 Late 1970s Katrina Leung is contacted by the FBI pm According to sources close to Katrina, she is first recruited by the FBI while living in ISIS is in Chicago, where she was obtaining an MBA at the University of Chicago. Afghanistan, But Who Are They Really? November 17, 2015 / 1:59 pm 1979 "Tiger Trap" investigation begins “The Most Risky … Job Ever.” A source in China allegedly provides the U.S. -

Advanced Technology Acquisition Strategies of the People's Republic

Advanced Technology Acquisition Strategies of the People’s Republic of China Principal Author Dallas Boyd Science Applications International Corporation Contributing Authors Jeffrey G. Lewis and Joshua H. Pollack Science Applications International Corporation September 2010 This report is the product of a collaboration between the Defense Threat Reduction Agency’s Advanced Systems and Concepts Office and Science Applications International Corporation. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Report Number ASCO 2010-021 Contract Number DTRA01-03-D-0017, T.I. 18-09-03 The mission of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) is to safeguard America and its allies from weapons of mass destruction (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high explosives) by providing capabilities to reduce, eliminate, counter the threat, and mitigate its effects. The Advanced Systems and Concepts Office (ASCO) supports this mission by providing long-term rolling horizon perspectives to help DTRA leadership identify, plan, and persuasively communicate what is needed in the near-term to achieve the longer-term goals inherent in the Agency’s mission. ASCO also emphasizes the identification, integration, and further development of leading strategic thinking and analysis on the most intractable problems related to combating weapons of mass destruction. For further information on this project, or on ASCO’s broader research program, please contact: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office 8725 John J. -

Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: Chinese Human Intelligence Operations Against the United States

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: Chinese Human Intelligence Operations against the United States Peter Mattis Fellow, The Jamestown Foundation June 9, 2016 China’s intelligence services are among the world’s most active against the United States, but the Chinese approach to human intelligence (HUMINT) remains misunderstood. Observers have conflated the operations of the intelligence services with the amateur clandestine collectors (but professional scientists/engineers/businesspeople) who collect foreign science and technology. The Chinese intelligence services have a long professional history, dating nearly to the dawn of the Chinese Communist Party, and intelligence has long been the province of professionals. The intelligence services were not immune to the political purges and the red vs. expert debates, and the Cultural Revolution destroyed much of the expertise in clandestine agent operations.1 As China’s interests abroad have grown and the blind spots created by the country’s domestic-based intelligence posture have become more acute, the Chinese intelligence services are evolving operationally and becoming more aggressive in pursuit of higher-quality intelligence. * * * The principal intelligence services conducting HUMINT operations, both clandestine and overt, against the United States are the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and Joint Staff Department’s Intelligence Bureau (JSD/IB) in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Prior to the military reforms announced in November 2015, the latter was known as the General Staff Department’s Second Department (commonly abbreviated 2PLA). Because the full ramifications of the PLA’s reform effort have unclear implications for intelligence, the testimony below will reflect what was known about 2PLA rather than the JSD/IB, unless specifically noted. -

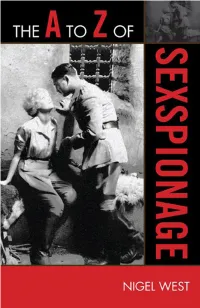

Nigel West, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

Clandestine HUMINT Asset Recruiting

Clandestine HUMINT asset recruiting From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is a subset article under Human Intelligence. For a complete hierarchical list of articles, see the intelligence cycle management hierarchy. Concepts here are also associated with counterintelligence. This article deals with the recruiting of human agents. For more general descriptions of human intelligence techniques, see the article on Clandestine HUMINT operational techniques. This article contains instructions, advice, or how-to content. The purpose of Wikipedia is to present facts, not to train. Please help improve this article either by rewriting the how-to content or by moving it to Wikiversity or Wikibooks. (September 2009) This article is written like a personal reflection or essay and may require cleanup. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (May 2008) This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Please consider splitting content into sub-articles and using this article for a summary of the key points of the subject. (September 2009) This section deals with the recruiting of human agents who work for a foreign government, or other targets of intelligence interest. For techniques of detecting and "doubling" host nation intelligence personnel who betray their oaths to work on behalf of a foreign intelligence agency, see counterintelligence. The term spy refers to human agents that are recruited by intelligence officers of a foreign intelligence agency. The popular use of the term in the media is at variance with its use in a professional context. Spies are not intelligence officers. Spies are recruited by intelligence officers to betray their country and to engage in espionage in favor of a foreign power. -

A Review of the FBI's Handling and Oversight of FBI Asset Katrina Leung

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General i • . | m ............. i A Review of the FBI's Handling and Oversight of FBI Asset Katrina Leung. (U) Unclassified Executive Summary Office of the Inspector General May 2006 EXECUTI_ SUMMARY I. Introduction In May 2000, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) receiw_d credible information that Katrina Leung, one of the FBI's most highly paid assets, was actively spying for the People's Republic of China (PRC) against the United States. 1 A year later, the FBI began an investigation that led to the discovery that Leung had been involved in an intimate romantic relationship witZh her handler of 18 years, Special Agent James ,J. Smith, who retired from the FBI in November 2000, The investigation also revealed that Leung had been involved in a sporadic affair with William Clevdand, another highly regarded FBI Special Agent, who retired from the FBI in 1993. The FBI's investigation further established that over theyears, FBI officials had lea:reed of several incidents indicating that Leung had provided classified U.S. government information to the PRC without FBI authorization. During the 18 years Leung was an asset, the FBI paid her over $1.7 million in services and expenses. In April 2003, Smith and Leung were arrested. FBI Director Robert Mueller asked the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) to reviewthe FBI's handling of Leung and the performance and management isSues relating to her case, and to recommend changes to improve FBI procedures and •practices where necessary. The OIG's investigation revealed that the FBI did little or nothing to resolve the numerous counterintelligence concerns that arose during Smith's handling of Leung. -

Too Many Resources? It's Unclear Why the Situation in Upstate New York Is

Too Many Resources? It's unclear why the situation in upstate New York is more serious than in other parts of the country, including areas with high border traffic volumes, like Detroit and northeastern Washington State. Some university officials and immigration lawyers suspect that Customs and Border Protection's Rochester station has been given more resources than it knows what to do with, reportedly expanding from seven to 27 agents since May 2008. There are no ports of entry in its jurisdiction, which lacks a land boundary with Canada. "Basically they have nothing to do, so they've come up with a really easy way to arrest a lot of people through internal enforcement," says Nancy Morawetz, ofthe New York University School ofLaw, who has represented individuals caught up in the sweeps and procured arrest information from Customs and Border Protection via the Freedom of Information Act. The records have shown that less than 1 percent of those arrested on buses and trains in the Rochester area had entered the country within the past three days, and that none of them could be shown to have entered from Canada, she says. "I think that data is incredibly powerful," Ms. Morawetz says, "because it shows that all this aggravation and hardship has essentially nothing to do with the Border Patrol mission" of securing the border. "In a country where 5 percent of the population lacks status, it's not hard to pick up bodies by going into any crowded station and asking people where they were born," she says. "This isn't about securing our borders. -

Third Raleigh International Spy Conference

Third Raleigh International Spy Conference It’s a pleasure to be with you this Friday morning to discuss China and the threat it poses to the national security of the United States. That threat is not of the future, but is increasingly being recognized as a current threat that must be dealt with sooner, not later, though it isn’t clear that we, as a nation, are prepared to do just that. I should tell you that I do not consider myself to be an expert on China. I have had the privilege of meeting a few over the years and frankly, they are few and far between. China is simply too large in size, too populous, too ethnically diverse, too complicated politically and socially to allow for a full understanding. To be conversant, about Beijing and Shanghai is not to be knowledgeable about China as a whole. What about Guangzhou and Shenyang and Fujian Province and the Yangtze River? Those regions too, play an important role in the huge land mass we simply call “China.” This is Zhongguo, what the Chinese call their country, meaning literally, “Middle Country” for they are, in their minds, the geographical center of the universe and of course, the cultural center of the world as well. But I’ve had some experiences, I’ve had some observations and, of course, I have some opinions that I am willing to share with you about China and the intelligence threat it poses to the United States. But let us look at China and how it got where it is. -

Katrina Leung Was a Temptress, Beguiled by the World of Intrigue, but Was She an Agent of Influence for Beijing, As Prosecutors Now Charge?

U.S.News & World Report CHINA DOLL Katrina Leung was a temptress, beguiled by the world of intrigue, but was she an agent of influence for Beijing, as prosecutors now charge? By Chitra Ragavan explained: A Chinese-American woman working as an intelligence asset for an fbi agent in Los Angeles had hen I. C. Smith and Bill Cleveland tipped off the mss about their trip. Smith was dumb- stepped off the plane in Beijing on Nov. founded. But he put the matter aside, assuming the fbi 30, 1990, nothing prepared them for would can the woman for the security breach: “I as- the reception they were about to re- sumed she would be closed as a source.” W ceive. The two fbi agents had been dis- She wasn’t. It was not until more than 12 years later, patched to assess security at the American Embassy, in fact—in April of this year—that the source of the leak a low-profile assignment. But from the moment they was finally arrested. According to the fbi, she is Kat- arrived, Smith and Cleveland were placed under heavy rina Leung, a prominent Chinese-American bookstore surveillance by the Ministry of State Security, China’s owner, business consultant, and Republican fundrais- kgb. “They were covering me,” Smith recalls, “like er. The fbi now says that Leung, in addition to her a blanket.” many other accomplishments, was a top-drawer Chi- It was as if the mss knew who the agents were. Smith nese spy. A key source of the secrets Leung allegedly finally understood why five months later, when Cleve- purveyed to her Chinese handlers, prosecutors allege, land called him from San Francisco.