Understanding Escape: the Development of the British-Led Escape Organisation, the Pat Line, 1940-1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Room Leaflet

Guest room locations Locations: Bield, Hanover (Scotland) & Trust Please find a list of the locations where guest bedrooms are available. For booking, and for specific details of the accommodation and facilities provided at each location, please contact the individual development. Telephone Council Area Development number Landlord Aberdeen Aberdeen - Ashley Grove, Great Western Road, AB10 6WE 01224 575 159 Hanover Aberdeen - Bridge of Dee Court, Holburn Street, AB10 7HG 01224 572 741 Hanover Aberdeen - Rosewell Gardens, AB15 6HZ 01224 324 089 Hanover Aberdeen - Strachan Mill Court, Leadside Road, AB25 1TX 01224 647 515 Hanover Aberdeenshire Banchory - Hanover Court, Station Road, AB31 5ZA 01330 822 921 Hanover Banff - Airlie Gardens, Low Street, AB45 1AZ 01261 815 796 Hanover Banff - Doo'cot View, St Combs Court, AB45 1GD 01261 815 946 Hanover Huntly - Granary Street, AB54 8AR 01466 793 728 Hanover Inverbervie - Hanover Court, DD10 0TR 01561 361 188 Hanover Inverurie - Hanover Court, Cuninghill Road, AB51 3WD 01467 624 179 Hanover Lumsden - Hanover Court, Main Street, AB54 4JF 01464 861 796 Hanover Macduff - Doune Court, Church Street, AB44 1UR 01261 832 906 Hanover Peterhead - Strawberry Bank, Eden Drive, AB42 2AA 01779 479 918 Hanover Stonehaven - Hanover Court, David Street, AB39 2FD 01569 764 595 Hanover Stonehaven - Turners Court, Ironfield Lane, AB39 2AE 01569 765 595 Hanover Tarves - Hanover Court, New Road, AB41 7LG 01651 851 559 Hanover Angus Brechin - South Port, Union Street, DD9 6HS 01356 624247 Bield Forfar - Kirkriggs Court, -

L'ancien Dirigeant Nationaliste Corse François Santoni a Été Assassiné

DIX NOUVELLES POUR L’ÉTÉ a « Les sandales », un texte inédit de Jorge Semprun www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17592 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE -- SAMEDI 18 AOÛT 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI L’assassinat de Santoni fragilise la paix en Corse b Ancien homme fort du FLNC, François Santoni a été tué, vendredi peu après 1 heure, dans un village de Corse-du-Sud b Ses assassins l’ont abattu d’une rafale de fusil d’assaut à la sortie d’un mariage b Soupçonné d’avoir créé Armata Corsa, il s’opposait aux nouveaux dirigeants nationalistes b Sa mort relance la polémique sur le processus de Matignon LE NATIONALISTE corse Fran- des « militaires » sur les « politi- çois Santoni, ancien chef d’A Cun- ques », François Santoni se savait colta Naziunalista, vitrine du menacé. Il passait pour avoir été à FLNC-canal historique, a été assas- l’origine de la création d’Armata siné, vendredi 17 août au matin, Corsa, groupe clandestin s’oppo- PHILIPPE GAUCKLER peu après 1 heure, dans le village sant au processus de Matignon. de Monacia-d’Aullène (Corse-du- Depuis sa création, en juin 1999, TECHNOLOGIE Sud). Ce meurtre, qui n’avait pas Armata Corsa a revendiqué trois été revendiqué à la mi-journée, fra- assassinats et une vingtaine d’at- gilise le processus de négociations tentats en Corse. Peut-on aimer politiques en cours en Corse. L’assassinat de François Santoni Agé de quarante et un ans, Fran- survient un an après celui de son çois Santoni a essuyé une rafale de ami Jean-Michel Rossi (tué le un robot ? fusil d’assaut de calibre 7,62, alors 7 août 2000 à L’Ile-Rousse, en qu’il sortait du mariage d’un ami et Haute-Corse). -

SHOP: HOUSING OPTIONS List of Developments Definitions of Housing Type

SHOP: HOUSING OPTIONS List of Developments Definitions of Housing Type Introduction most benefit from full central heating, good Anyone aged 16 and over is free to apply for any insulation, and have security and safety features type of housing, however, some types of housing such as good locks and protective design, are designed for the special needs of specific including smoke alarms. As there are no ‘on site’ groups, such as older people, and will be staff, amenity housing is more suitable for people allocated in accordance with the landlords’ who are able to live independently. However allocations policies. properties are linked to an emergency call system which gives 24 hour access through a call centre. General Needs General needs housing will accommodate a range Sheltered Housing of applicants – single people, couples or families, Sheltered housing provides a range of services and varies in design and house size. However and facilities designed to meet the needs of general needs housing is not specifically tenants. The three SHOP landlords generally designed to suit specialised physical needs. provide sheltered housing for older people aged 60 years and above. However younger people Amenity Housing who demonstrate a need for it may sometimes Amenity housing is aimed at people with be accommodated in sheltered housing if it is particular needs however the three SHOP considered that they would benefit from the landlords predominately provide amenity housing services, for example, because of a medical for older people aged 60 years and above. Most condition or physical disability. Personal care and amenity houses are self-contained with living support to tenants is not provided by the SHOP room, bedroom, kitchen and bathroom or shower- landlords, but can be provided by the local room. -

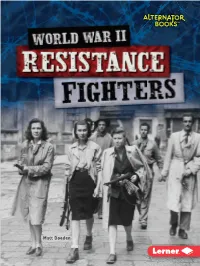

Matt Doeden THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Matt Doeden

DOEDEN Matt Doeden THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Matt Doeden Lerner Publications Minneapolis Content consultant: Eric Juhnke, Professor of History, Briar Cliff University Copyright © 2018 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Doeden, Matt, author. Title: World War II resistance fighters / by Matt Doeden. Description: Minneapolis : Lerner Publications, [2018] | Series: Heroes of World War II | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grades 4–6. | Audience: Ages 8–12. Identifiers: LCCN 2017010790 (print) | LCCN 2017011941 (ebook) | ISBN 9781512498196 (eb pdf) | ISBN 9781512486414 (lb : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Anti-Nazi movement—History—20th century—Juvenile literature. | Anti-Nazi movement—Europe—Biography—Juvenile literature. | Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Juvenile literature. | Germany— History—1933–1945—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC DD256.3 (ebook) | LCC DD256.3 .D58 2018 (print) | DDC 940.53/1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010790 Manufactured in the United States of America 1-43465-33205-6/14/2017 CONTENTS Introduction Teenage Terror 4 Chapter 1 Acts of Sabotage 8 Chapter 2 Knowledge Is Power 14 Chapter 3 Rescue Operations 18 Chapter 4 Rising Up 22 Timeline 28 Source Note 30 Glossary 30 Further Information 31 Index 32 INTRODUCTION TEENAGE TERROR Eighteen-year-old Si mone Se gouin stayed low. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Palestine in Irish Politics a History

Palestine in Irish Politics A History The Irish State and the ‘Question of Palestine’ 1918-2011 Sadaka Paper No. 8 (Revised edition 2011) Compiled by Philip O’Connor July 2011 Sadaka – The Ireland Palestine Alliance, 7 Red Cow Lane, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Ireland. email: [email protected] web: www.sadaka.ie Bank account: Permanent TSB, Henry St., Dublin 1. NSC 990619 A/c 16595221 Contents Introduction – A record that stands ..................................................................... 3 The ‘Irish Model’ of anti-colonialism .................................................................... 3 The Irish Free State in the World ........................................................................ 4 The British Empire and the Zionist project........................................................... 5 De Valera and the Palestine question ................................................................. 6 Ireland and its Jewish population in the fascist era ............................................. 8 De Valera and Zionism ........................................................................................ 9 Post-war Ireland and the State of Israel ............................................................ 10 The UN: Frank Aiken’s “3-Point Plan for the Middle East” ................................ 12 Ireland and the 1967 War .................................................................................. 13 The EEC and Garret Fitzgerald’s promotion of Palestinian rights ..................... 14 Brian Lenihan and the Irish -

American Airmen Shot Down Over Europe Had a Sophisticated Web Of

USAF photo emember: Do Nothing. Say Nothing. Write Nothing Which “ Could Betray Our Friends.” This notice, posted for American airmen shot down over aircrew during World War II, Rreminded them of a reassuring secret: Europe had a sophisticated web of If they were shot down over France, Resistance networks were ready and eager supporters for attempts to avoid the to hide them from the Germans. Nazis and reach freedom. There was good reason to be optimistic. The Resistance enabled more than 3,000 Allied airmen to disguise their identities and walk out of German-occupied Western Europe. Airmen shot down in France and Belgium had especially good chances of making it out. Future American ace and test pilot legend Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager was shot down by Focke-Wulf 190s on a mission over France on March 5, 1944. “Before I had gone 200 feet, half a dozen Frenchmen ran up to me,” Yeager later reported. They brought him a change of clothes and hid him in a barn. Under the care of the Resistance, Yeager was transported to southern France, hiked into Spain on March 28, reached the British fortress at Gibraltar on May 15, and was in England by May 21, 1944. Yeager’s speedy trip was made possible by years of effort to build networks for moving airmen from the moment they landed in their parachutes to the moment they reached friendly or neutral territory. The evading airman’s journey always began with immediate concealment. Then they sheltered with families, often in several locations. Next they traveled in cars and trucks, bicycled, and even rode A B-24 crash-lands near Eindhoven, Holland. -

1815, WW1 and WW2

Episode 2 : 1815, WW1 and WW2 ‘The Cockpit of Europe’ is how Belgium has understatement is an inalienable national often been described - the stage upon which characteristic, and fame is by no means a other competing nations have come to fight reliable measure of bravery. out their differences. A crossroads and Here we look at more than 50 such heroes trading hub falling between power blocks, from Brussels and Wallonia, where the Battle Belgium has been the scene of countless of Waterloo took place, and the scene of colossal clashes - Ramillies, Oudenarde, some of the most bitter fighting in the two Jemappes, Waterloo, Ypres, to name but a World Wars - and of some of Belgium’s most few. Ruled successively by the Romans, heroic acts of resistance. Franks, French, Holy Roman Empire, Burgundians, Spanish, Austrians and Dutch, Waterloo, 1815 the idea of an independent Belgium nation only floated into view in the 18th century. The concept of an independent Belgian nation, in the shape that we know it today, It is easy to forget that Belgian people have had little meaning until the 18th century. been living in these lands all the while. The However, the high-handed rule of the Austrian name goes back at least 2,000 years, when Empire provoked a rebellion called the the Belgae people inspired the name of the Brabant Revolution in 1789–90, in which Roman province Gallia Belgica. Julius Caesar independence was proclaimed. It was brutally was in no doubt about their bravery: ‘Of all crushed, and quickly overtaken by events in these people [the Gauls],’ he wrote, ‘the the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. -

129 2020.Pdf

THETHE COVERTCOVERT WORLDWORLD OFOF ESPIONAGEESPIONAGE ® INTELLIGENCE MAGAZINE £4.25 NUMBER 129 2020 •MOSSAD & UNIT 8200 •EDWARD SNOWDEN • COZY BEAR CYBER MENACE •UAE-ISRAEL ACCORDS •RUSSIA INTERFERENCE •MI9 WWII OPERATIONS •WEAPONISING SPACE •FBI COUNTER-ESPIONAGE STING •IRAN SPY GAMES THE MI6 SPYMASTER COVID-19 VACCINE 13 GRU Cyber Group APT28 - Cozy Bear - in Worldwide Hunt for Advanced Research 18 Richard Moore CHASING THE HOLY GRAIL UK Foreign Intelligence Service - New Chief EXTREME PREJUDICE HOUSE OF SPIES 48 26 New Novichok Sanction Intelligence hands behind attempted CHINA INTEL FOCUS assassination of Kremlin critic Navalny WIZARDS OF FEAR 52 56 THE A-Z LANGUAGE OF SPIES The secret Kremlin intel programme targeting US troops in Afghanistan EDWARD SNOWDEN THE INSPECTOR White House 71 Opens Gateway to America for NSA Leaks More rogue Russian satellite activity Man monitored by West 31 2 EYE SPY INTELLIGENCE MAGAZINE 129 2020 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ “Russia poses the greatest military and geopolitical threat to European EYE SPY 129 security. China is increasingly authoritarian and assertive. It poses the greatest threat to world order...” ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ VOLUME XVII NUMBER ONE 2020 (ISSUE 129) Lt. General Hockenhull, UK Chief of Defence Intelligence ISSN 1364 8446 publication date: SEPT/OCT 2020 FRONT COVER MAIN IMAGE: GETTY CHINA AND RUSSIA: ESPIONAGE, INFLUENCE & PROPAGANDA Established December 2000 Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic continues to cause major disruption, distress and sorrow around the world, the great game of espionage is still being played. Intelligence is a 24-hour-a-day highly specialised field that for a multitude of reasons will always remain active, though here too agencies have had to alter work practices and put a hold on planned operations - though not all. -

New Document Releases MI5 Files Introduction These Pages Offer A

New Document Releases MI5 Files Introduction These pages offer a brief overview and description of some of the most interesting files within the latest release of Security Service records. This is the seventh and largest Security Service release, consisting of approximately 200 files, bringing the total number of MI5 records in the Public Record Office to 919. As with previous releases, the bulk of records are personal files, relating to agents, double agents, intelligence officers and renegades, or those under suspicion of being so, the large proportion of which relate to Germany during the period 1939-45. However, this release does include a number of files under new categories, including refugees (KV 2/469- 482), pre-war Soviet intelligence officers (KV 2/483) and agents (KV 2/484- 485), right-wing extremists (KV 2/486-497), communists, communist sympathizers and communist front organisations (KV 2/498-513). There are also a number of policy and subject files. Highlights of the release described in these pages include: • Double agent SNOW (KV 2/444-453) • Double agent GW (KV 2/468) • Double agent ZIG ZAG (KV 2/455-463) • Double agent TREASURE (KV 2/464-466) • Eamon De Valera (KV 2/514-515) • Leon Trotsky (KV 2/502-505) • Grigori Zinoviev (KV 2/501) • Harold Cole (KV 2/415-417) - A British soldier who betrayed Allied escape lines, resulting in the deaths of over 50 people. • Otto Skorzeny (KV 2/403) - SS officer who liberated Mussolini in September 1943 and trained a group of special agents. • Kurt Wieland (KV 2/400-402) - Leader of a small German/Arab paratroop subversive group directed against Jews in Palestine. -

It's Official! Acommander for Clan Baird

It's official! ACommander for Clan Baird Dr. Debra Baird, FSA Scot President, Clan Baird Society Worldwide, Inc. On August 5'h'2019, Carrick Pursuivant, Sir Richard Holman Baird and foxhounds George Way of Plean, heard the arguments for Clan tion during the meeting. They were Andrew Baird of Baird to have a Commander named and after a three- Newbyth, Sir James Baird of Saughtonhall, and Ri- hour council with 73 Bairds from around the wor1d, chard Holman-Baird of Rickarton, Ury and as well as several by ZOOM video conference, Rich- Lochwood. ard Holman-Baird of Rickarton, Ury and Lochwood, After the voting, the new Commander, Richard was elected overwhelmingly. Holman-Baird, asked all the named Chieftains of Clan Joseph Later in August, the Lord Lyon, Dr. Baird Society Worldwide, to help him bring al1 the The Morrow, commissioned Richard as our leader. family lines together and work together. were in attendance at the photograph is ofthose who I hope that his plea is heeded by a1l ofus and Family Convention. There were three nominees who stood for elec- Continued on page 29 lf you have genealogicaf ties to the surnarne Keith (lncluding alternate spellings such as Keeth.) @!" any of Glan Keith's Sept family names! you were born into the Clan Keithl Associated Family Surnannes (Septs) with NMac on lMc prefixes and spelling variants include: Septs and spellings inclulde: Atlstin, Cate(s), Dick, Dickie, Dicken, Dickson, Dicson, Dixon, Dixson, Faleoner, Faulkner, Harvey, Harvie, Hackston, Haxton, f'larvey, Hervey, Hurrie, Hurry, Keath, Keech, Keeth, Keith, Keitch, Keithan, Keyth, Kite, Lum, Lumgair, lMarshall, Urie, Urry. -

Confidence Men the Mediterranean Double-Cross System, 1941-45 By

Confidence Men The Mediterranean Double-Cross System, 1941-45 by Brett Edward Lintott A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © Copyright by Brett Edward Lintott, 2015 Abstract Confidence Men The Mediterranean Double-Cross System, 1941-45 Brett Edward Lintott Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto, 2015 This dissertation provides an analysis of the Mediterranean double-cross system of the Second World War, which was composed of a number of double agents who were turned by the Allies and operated against their ostensible German spymasters. Utilizing many freshly released archival materials, this study assesses how the double-cross system was constructed, why it was an effective instrument, and how it contributed to Allied success in two areas: security and counter-intelligence, and military deception. The focus is thus on both organization and operations. The chapters cover three chronological periods. In the first — 1941-42 — the initial operational usage of a double agent is assessed, along with the development of early organizational structures to manage and operate individual cases as components of a team of spies. The second section, covering 1943, assesses three issues: major organizational innovations made early that year; the subsequent use of the double agent system to deceive the Germans regarding the planned invasion of Sicily in July; and the ongoing effort to utilize double agents to ensure a stable security and counter-intelligence environment in the Mediterranean theatre. The third and final section analyzes events in 1944, with a focus on double-cross deception in Italy and France, and on the emergence of more systematic security and counter-intelligence double-cross operations in Italy and the Middle East.