Jean Françaix, 1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

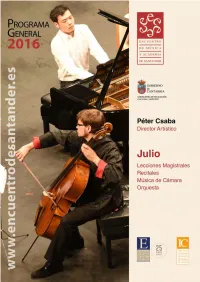

Programa2016.Pdf

l Encuentro de Música y Academia cumple un año más el reto de superarse a sí mismo. La programación de 2016 combina a la perfección la academia, la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los más grandes, como el maestro Krzysztof Penderecki, con la frescura, las ganas y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos Eparticipantes en esta cita ineludible cada verano en Cantabria. Más de 50 conciertos en los escenarios del Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, en el Palacio de La Magdalena y en otras 22 localidades acercarán la Música con mayúsculas a todos los rincones de la Comunidad Autónoma para satisfacer a un público exigente y siempre ávido de manifestaciones culturales. Para esta tierra, es un privilegio la oportunidad de engrandecer su calendario cultural con un evento de tanta relevancia nacional e internacional. Así pues, animo a todos los cántabros y a quienes nos visitan en estas fechas estivales a disfrutar al máximo de los grandes de la música y a aportar con su presencia la excelente programación que, un verano más, nos ofrece el Encuentro de Música y Academia. Miguel Ángel Revilla Presidente del Gobierno de Cantabria esde hace ya 16 años, el Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander sigue fielmente las líneas maestras que lo han convertido en un elemento muy prestigioso del verano musical europeo. En Santander —que es una delicia en el mes de julio— se reúnen jóvenes músicos seleccionados uno a uno mediante audición en las escuelas de mayor prestigio Dde Europa, incluida, naturalmente, la Reina Sofía de Madrid. Comparten clases magistrales, ensayos y conciertos con una serie igualmente extraordinaria de profesores, los más destacados de cada instrumento en el panorama internacional. -

Kosten Los 1-Mal KOSTENLOS Für Summerwinds-Gäste! Ganz Nah ! Rufen Sie Einfach an (Tel.: 02 51.41 32-213) Oder Senden Sie Eine Mail an [email protected]

Kosten los 1-mal KOSTENLOS für Summerwinds-Gäste! ganz nah ! Rufen Sie einfach an (Tel.: 02 51.41 32-213) oder senden Sie eine Mail an [email protected] Der Westfalenspiegel wünscht hülsta woodwinds TALENT IST WIE EIN JUNGER BAUM – MIT HINGABE GEPFLEGT, Ihnen schöne Hörerlebnisse! International Woodwind Competition ÜBERRASCHT ES UNS DURCH SEINE EINZIGARTIGKEIT. „hülsta woodwinds“-Preisträger beim Internationalen Holzbläser Festival „summerwinds“: 27.07.2012 | 20:00 Uhr | Bartek Dus´ , Saxofon | Lüdinghausen | Burg Vischering 25.08.2012 | 18:00 Uhr | Zeynep Köylüoglu, Fagott | Rheine | Kloster Bentlage www.huelsta.de IRGENDWANN MUSS ES HÜLSTA SEIN. 12-ardey-2-anzeige-summerwinds.indd 1 17.04.12 11:00 Liebe Musik- und Kulturfreundinnen und -freunde, Wind und Atem, Hauch und Geist sind schon seit biblischen Zeiten Ich danke allen Förderpartnern und Sponsoren und all unseren en- verbunden im hebräischen „ruach“, im griechischen „pneuma“ und gagierten Kooperationspartnern vor Ort für die unkomplizierte und nach dem großen Erfolg der Erstausgabe von „summerwinds“ vor zwei Jahren im lateinischen „spiritus“. Im Wind ist Jahwe, ist der christliche Gott. beglückende Zusammenarbeit. freuen wir uns auf ein Wiederaufleben der Winde in diesem Sommer, einen Atem ist Metapher für Seele und Leben, für ein Unsichtbares, das un- tiefblauen Himmel mit leuchtenden Stars und hell aufgehenden Sternen, die greifbar und unbegreiflich bleibt. So auch bei SUMMER SINGS, Ihnen, liebe Gäste von nah und fern, wünsche ich, auch im Namen mitnehmen auf inspirierende Reisen durch die Zeiten und die Welten „zwi- dem offenen Singen für alle. Und bei INSPIRIERT geht‘s wort- aller unserer Partner, einen zweiten wunderwindigen Sommer. schen dem Garten Eden und dem Himmlischen Jerusalem“. -

Mei 2019 Eerste Communie Derde Zondag in De Paastijd

Elke week Muziek in Sint-Paulus 1 01/5 - Koorhappening: uitgesteld 2 05/5 - Eerste Communie 3 12/5 - Solistenmis 4 19/5 - Gregoriaanse koormis 12 26/5 - Orgelmis 14 26/5 - Concert: Un viaggio particolare 15 30/5 - Solistenmis O.L.H. Hemelvaart 16 De Sint-Paulusparochie viert haar pastoor 18 Utopia Festivaldag 2019 20 Steunfonds Artistieke Werking 24 Muziek in Sint-Paulus Elke week muziek in de Antwerpse Sint-Pauluskerk Raadpleeg onze nieuwe jaarkalender indien u op de hoogte wenst te blijven van de muzikale invulling van de vieringen in Sint-Paulus. U vindt een exemplaar bij het verlaten van de kerk, op de tafel aan de uitgang Sint-Paulusstraat of aan de balie bij de uitgang Veemarkt. U merkt dat we niet enkel de traditie van de orkestmissen hoog houden maar dat er elke week een boeiend muzikaal-liturgisch gebeuren is in Sint-Paulus. Naast de 9 orkestmissen zijn er ook 12 solistenmissen met vooraanstaande musici, mooi verdeeld in 6 vocale en 6 instrumentale missen. Er zijn ook 5 Gregoriaanse missen, diverse koormissen en natuurlijk de orgelmissen die door onze titularis-organist virtuoos worden ingevuld. Elke maand wacht er bovendien een nieuwe brochure op u waarin u het aanbod gedetailleerd voorgesteld vindt. Alle informatie vindt u ook op onze website: www.muziekinsintpaulus.be Of raadpleeg en like onze facebookpagina: Muziek in Sint-Paulus (www.facebook.com/MuziekInSintPaulus) I KOORHAPPENING De koorhappening van 1 mei – kennismaking met de Messe Brève nr 7 van Charles Gounod – werd UITGESTELD wegens onvoorziene omstandigheden uitgesteld naar latere datum. Meer nieuws daarover in onze juni editie. -

IFPI Norges Årsrapport

Musikkåret 2017 IFPI Norges årsrapport SIGRID Foto: Petroleum Records Design: Anagramdesign . no Innhold årsrapport 2017 Innledning ................... 3 KYGO ....................... 5 Sammendrag av musikk- undersøkelsen 2017 ........... 6 Statistikk..................... 7 Fornyelse av opphavsretten i Norge og Europa – del 2 ..... 10 Cezinando ................... 11 Spellemann 2017 ............ 12 Astrid S..................... 14 United Screens – Topplista.... 15 Hkeem & Temur ............. 16 FORSIDE: Alan Walker ................. 17 Streaming topp20 2017 ...... 18 Streaming, norsk topp20 2017 19 SIGRID Album topp20 2017......... 20 Norges nye popkomet tok oss med storm Radio topp20 2017 .......... 21 Totalsalget av innspilt med låten «Don’t Kill My Vibe» i 2017. Hun fikk mye oppmerksomhet internasjo- Gabrielle .................... 22 musikk i Norge går opp nalt og var både på «The Tonight Show Seeb ....................... 23 2,1 % fra 2016 til 2017 starring Jimmy Fallon» og «The Late Late Troféoversikt 2017 ........... 24 Show with James Cordon». Etter flere kon- og streaming står nå serter både i Norge og i utlandet, har hun IFPI Insight 2017............. 26 for hele 85 % av salget. også vært opptatt med å lage sin debut Vidar Villa................... 27 album som forhåpentligvis kommer ut Dagny ...................... 28 i 2018. Hun var nominert til to priser under Spellemann 2017 og vant prisen for Årets IFPI Norge .................. 29 Nykommer & Gramostipend. 2 Innledning 2017 var et nytt godt år i norsk musikkindustri og nordmenn fortsetter å streame musikk som aldri før. Totalsalget av innspilt musikk i Norge er opp 3,7 % fra 2016 til 2017 og streaming står nå for hele 85 % av salget av innspilt musikk i Norge. Årstallene for 2017 viser at det ble solgt Det totale fysiske salget (CD, vinyl osv.) innspilt musikk for hele kr. -

Instructions for Authors

Journal of Science and Arts Supplement at No. 2(13), pp. 157-161, 2010 THE CLARINET IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE 20TH CENTURY FELIX CONSTANTIN GOLDBACH Valahia University of Targoviste, Faculty of Science and Arts, Arts Department, 130024, Targoviste, Romania Abstract. The beginning of the 20th century lay under the sign of the economic crises, caused by the great World Wars. Along with them came state reorganizations and political divisions. The most cruel realism, of the unimaginable disasters, culminating with the nuclear bombs, replaced, to a significant extent, the European romanticism and affected the cultural environment, modifying viewpoints, ideals, spiritual and philosophical values, artistic domains. The art of the sounds developed, being supported as well by the multiple possibilities of recording and world distribution, generated by the inventions of this epoch, an excessively technical one, the most important ones being the cinema, the radio, the television and the recordings – electronic or on tape – of the creations and interpretations. Keywords: chamber music of the 20th century, musical styles, cultural tradition. 1. INTRODUCTION Despite all the vicissitudes, music continued to ennoble the human souls. The study of the instruments’ construction features, of the concert halls, the investigation of the sound and the quality of the recordings supported the formation of a series of high-quality performers and the attainment of high performance levels. The international contests organized on instruments led to a selection of the values of the interpretative art. So, the exceptional professional players are no longer rarities. 2. DISCUSSIONS The economic development of the United States of America after the two World Wars, the cultural continuity in countries with tradition, such as England and France, the fast restoration of the West European states, including Germany, represented conditions that allowed the flourishing of musical education. -

Do You Believe in Heather? an Energizing Vitality

Ståle Kleiberg is often called a “modern romantic”, and for good reason. We encounter a distinctive and highly individual alloy of modern and romantic elements in his music, whether it is characterized by a still, meditative lyricism or Do You Believe in Heather? an energizing vitality. His String Quartet no. 3 encompasses this entire range of — chamber music by Ståle Kleiberg expression. The music speaks of summer. It is imbued with joie de vivre, and was composed with a full command of the genre and with considerable virtuosity. The flute-viola-harp ensemble is less common, but by no means unknown. Following Debussy’s Sonata, several trios have been composed for this ensemble, and Kleiberg’s Trio Luna is a fine and most welcome addition. The work’s three movements capture the mood of three dissimilar outer and inner landscapes, all of them bathed in moonlight, albeit at different times of day and night. The Light Smith is also a trio; it is a song cycle for mezzo-soprano, clarinet and piano, and is chamber music on a very high level of inspiration. Both The Light Smith and Do You Believe in Heather? are settings of poetry by the distinguished Norwegian poet Helge Torvund. These poems engage with such archetypal themes as light, quietude, love, death and nature, but they treat these themes as real, everyday experiences, rather than abstract concepts. While the theme of The Light Smith centres on the beginnings, growth and culmination of life, it is autumn and winter we meet in Do You Believe in Heather? Marianne Beate Kielland, Ida Kateraas, Ole Christian Haagenrud, Atle Sponberg, Anders Larsen, Ole Wuttudal, Øyvind Gimse, Annika Nordstrøm, Jan Petter Hilstad, Ruth Potter 152 EAN13: 7041888524427 q e 5.1 surround and stereo recorded in DXD 24bit/352.8kHz 2L-152-SACD 20©19 Lindberg Lyd AS, Norway 7 041888 524427 literary image in “The Light Smith” unquestionably falling into this category. -

John Bruce Yeh

Vol. 48 • No. 1 December 2020 JOHN BRUCE YEH ICA Plays On! Anna Hashimoto Clarinet Works by Black Composers Krzysztof Penderecki’s Clarinet Works TO DESIGN OUR NEW CLARINET MOUTHPIECE WE HAD TO GO TO MILAN “I am so happy to play the Chedeville Umbra because it is so sweet, dark, so full of colors like when you listen to Pavarotti. You have absolutely all kind of harmonics, you don’t have to force or push, and the vibration of the reed, the mouthpiece, the material, it’s connected with my heart.” Milan Rericha – International Soloist, Co-founder RZ Clarinets The New Chedeville Umbra Clarinet Mouthpiece Our new Umbra Bb Clarinet Mouthpiece creates a beautiful dark sound full of rich colors. Darker in sound color than our Elite model, it also has less resistance, a combination that is seldom found in a clarinet mouthpiece. Because it doesn’t add resistance, you will have no limits in dynamics, colors or articulation. Each mouthpiece is handcrafted at our factory in Savannah Georgia Life Without Limits through a combination of new world technology and old world craftsmanship, and to the highest standards of excellence. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] hope this finds you well and staying safe as we continue EDITORIAL BOARD to navigate these truly extraordinary times. I also hope Diane Barger, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, that you are finding or creating opportunities to make Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder music, whether it be on your own, socially distanced MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR Iwith others or through a computer screen. -

Gustav Mahler Symphonie N° 6 « Tragique »

MARDI 27 AVRIL – 20H Ludwig van Beethoven Concerto pour piano n° 5 « L’Empereur » entracte Gustav Mahler Symphonie n° 6 « Tragique » Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio Suédoise Daniel Harding, direction Nicholas Angelich, piano Fin du concert vers 22h20. 2704 ANGELICH A5.indd 1 27/04/10 14:42 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Concerto pour piano et orchestre n° 5 en mi bémol majeur op. 73 « L’Empereur » Allegro Adagio un poco mosso Rondo. Allegro ma non troppo Composition : 1809. Création : le 28 novembre 1811 à Leipzig par Johann Schneider. Effectif : 1 flûte, 2 hautbois, 2 clarinettes, 2 bassons – 2 cors, 2 trompettes – timbales – cordes – piano solo. Durée : environ 40 minutes. Le dernier et le plus célèbre des concertos beethovéniens pour piano a été surnommé L’Empereur, sans doute par J. B. Cramer, et après la mort du compositeur ; probablement a-t-il voulu souligner la grandeur de l’ouvrage. En réalité, on sait que Beethoven n’aimait pas trop les têtes couronnées, et ce n’est certainement pas à Napoléon qu’il adressait son concerto : il a même dû en interrompre l’écriture à cause des bombardements français qui pleuvaient sur Vienne. Tapi au fond d’une cave avec des coussins sur la tête, le maître maugréait contre l’envahisseur : « Dommage que je ne sois pas aussi fort en stratégie qu’en musique : je le battrais ! » Bien que sur ses esquisses le compositeur ait noté : « Chant de triomphe pour le combat ! Attaque ! Victoire ! », ce concerto ne présente pratiquement aucun trait militaire ; il brille plutôt par son autorité naturelle, qui en fait le chef de file des concertos romantiques à venir. -

BOOKLET NOTES: BJØRN KRUSE / FREDRIK FORS Film, Theatre, Jazz, Opera and Classical Music

BJØRN KRUSE CHRONOTOPE CONCERTO FOR CLARINET AND ORCHESTRA FREDRIK FORS – CLARINET OSLO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CHRISTIAN EGGEN – CONDUCTOR BJØRN KRUSE Samarbeidet mellom solisten Fredrik Fors, BJØRN KRUSE The collaborative efforts of soloist Fredrik OM CHRONOTOPE dirigenten Christian Eggen og Oslo Filhar- ABOUT CHRONOTOPE Fors, conductor Christian Eggen and the Oslo moniske Orkester (OFO) sørger på optimal Philharmonic Orchestra excellently work in Tittelen Chronotope er et begrep som den måte for å få frem verkets konseptuelle in- The title Chronotope is a term used by the bringing out the work’s conceptual intention russiske språkfilosofen Mikhail Bakhtin tensjon og musikalske karakter. Fredrik opp- Russian literary philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin and musical character. Fredrik embodies all (1895-1975) benyttet for å betegne hvor- fyller alt jeg kunne ønske meg av en solist. (1895-1975) to describe how an awareness of that I could ever wish for in a soloist. He pos- dan forestillinger om tid og rom (chronos Han har en blendende teknikk og en vakker, time and space (chronos and topos) is repre- sesses a perfect virtuoso technique along og topos) oppstår i språk og oppleves i lyrisk klang, og forener begge disse egen- sented in language and discourse. I find that with a beautiful, lyrical clarinet sound; he fus- samtale. Jeg synes begrepet også kan an- skapene i et sterkt og intenst uttrykk som the term also naturally applies as a model to es these qualities into a powerful and intense vendes på musikk og musikalsk opplevelse, bærer verket videre utover min egen inten- the experience of temporal and spatial di- expression that elevates the work beyond my hvor minnet om noe som umiddelbart var, sjon, og gjør det også til sitt. -

Årsberetning 2012.Indd

Oslo Filharmoniske Orkester Årsrapport 2012 Årsrapport for Stiftelsen Oslo-Filharmonien 2012 Side 3 INNHOLD ÅRSRAPPort FOR STIFTELSEN OSLO-FILHARMONIEN 2012 KUNSTNERISK VIRKSOMHET SIDE 03 SPILLEROM SIDE 04 ARRANGementsoversikt SPILLEROM SIDE 06 PresseomtALER OSLO-FILHARMONIEN ER SAMFUNNSEIE, OG ALLE konserter ER FOR ALLE. SAMTIDIG vet VI AT TERSKELEN ER HØYERE FOR NOEN ENN FOR ANDRE. SPILLEROM TAR SPESIELT sikte PÅ Å SENKE TERSKELEN. SIDE 09 TURNEER OG GJestesPILL SIDE 11 KAmmerkonserter Store gratiskonserter på Rådhusplassen og Myraløkka I august ble konserten på Rådhusplassen arrangert for fjerde gang, nå med et besøk på ca. 25 000. I juni arrangerte vi SIDE 12 RADIO, FJERNSYN OG streAMING for første gang friluftskonsert på Myraløkka i Bydel Sagene med et besøk på ca. 5 000. På Rådhusplassen var det denne gang Eivind Aadland som dirigerte Beethovens 9. symfoni, og det sammensatte og populære programmet på Myraløkka SIDE 13 UTGIVELSER 2012 ble presentert av trompetist Tine Thing Helseth og dirigent Rolf Gupta, til stor jubel. SIDE 14 DIRIGENTER, SOLister OG ANDRE MEDVIRKENDE Sommerfestival Sagene sommerkonsert på Myraløkka inngikk i den festivalhelgen som også omfattet konserter i Freiasalen og på Park- SIDE 15 FREMFØrte VERK teatret. I 2013 blir festivalen utvidet med konserter også på Månefisken (Sagene), Riksscenen (Schous kulturbryggeri) Grünerløkka og Caféteatret (Grønland). SIDE 16 KORET Furuset og Alna bydel SIDE 17 PUBLikum I samarbeid med bydelen har forestillingen Patty og ulven (se under) vært satt opp på Rommen scene. Det er i 2012 også inngått avtale med bydelen om orkesterets medvirkning på Furusetdagene fra 2014. SIDE 18 H.M. DRONNING SONJA Star Wars-konserter SIDE 19 STØTTESPILLERE OG SAMARBEIDSPARTNERE John Williams’ musikk til Star Wars er svært populær hos alle aldersklasser, og de to konsertene i januar var helt full- satte. -

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH and BALTIC CONCERTOS from the 19Th Century to the Present a Discography of Cds and Lps Prepared by Michael

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH AND BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JĀNIS IVANOVS (1906-1983, LATVIA) Born in Riga. He studied conducting with Georg Schnéevoigt and composition with Jazeps Vitols at the Latvian Conservatory. He taught composition and orchestration at his former school (now known as the Latvian Academy of Music). In addition, he worked as a sound engineer for Latvian Radio and later became its artistic director. As a composer, his output centers around orchestral music, including 20 Symphonies, but he has also written chamber music, piano pieces, songs and film scores. Piano Concerto in G minor (1959) Konstantin Blumenthal (piano)/Edgars Tons/Latvian Radio Symphony Orchestra MELODIYA D7267-8 (LP) (1960) Nikolai Federovskis (piano)/Centis Kriķis//Latvian Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + 3 Sketches for Piano) MELODIYA SM 02743-4 (LP) (1971) Igor Zhukov (piano)/Vassily Sinaisky/Latvian National Television and Radio) Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 14 and 20) LMIC 035 (2013) (original LP release: MELODIYA S10-11829-30) (1980) Violin Concerto in E minor (1951) Juris Svolkovskis (violin)/Edgars Tons/Latvian Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Cello Concerto and Andante) MELODIYA 33S 01475-6) LP) (1967) Valdis Zarins (violin)Vassily Sinaisky/Latvian National (Television and Radio) Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1976) ( + Sibelius: Violin Concerto and Sallinen: Violin Concerto) CAMPION CAMEO CD 2004 (1997) (original LP release: MELODIYA S10-11829-30) (1980) Cello Concerto in B minor (1938) Ernest Bertovskis (cello)/Edgars Tons/Latvian Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Cello Concerto and Andante MELODIYA 33S 01475-6) LP) (1967) Ernest Bertovskis(cello)/Leonids Vigners/Latvian Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Vitols: Latvian Rustic Serenade and Valse Caprice) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 Scandinavian, Finnish & Baltic Concertos I-P MELODIYA ND1891-2 (LP) (1954) Mâris Villerušs (cello)/Leonids Vigners/Latvian National Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Sesongprogram 2017−2018

Oslo Filharmonien −+ Sesongen 2017–2018 Høytid – hver uke 2016 ble nok et år med billettsalgsrekord for Oslo-Filharmonien. Onsdagsserien «Kort og klassisk» (én-times konserter uten pause) har størst økning og treffer særlig mange av dem som liker å gå alene på konsert, eller som bare ønsker litt musikalsk påfyll på vei hjem fra jobb. Men mangfoldet i opplevelsene vi tilbyr når i det hele tatt stadig flere publikumsgrupper. «Målet er at barna skal trygle om å få gå på klassisk konsert», sa Sigurd Slåttebrekk til Aftenposten, da prosjektet Musikkfabrikken ble lansert i 2015. Slåttebrekk, som både er klassisk konsertpianist © Trygve Indrelid og barne-tv-skaper, har laget en av sesongens familieforestillinger sammen med orkestret, med det digitale universet som en integrert del. Premieren i oktober 2017 er intet mindre enn en musikalsk oppdagelsesferd for barn. Opplev også en av verdens mest enestående pianister, Leif Ove Andsnes, ikke bare i én produksjon, men som sesongens artist med tre produksjoner, samlet i et eget abonnement. Fordyp deg i Schumanns fantastiske musikk i vår egen Schumann-festival, og opplev mektige symfonier, splitter nye verk og storslåtte kor- produksjoner i Oslo Konserthus, samt lekne kammerkonserter på Munchmuseet. Mange har som tradisjon at de feirer høytidene sammen med Oslo-Filharmonien. Billettene til jule-, nyttårs- og påske- konsertene rives bort. Men opplevelser som løfter, utfordrer og inspirerer kan nytes mye oftere enn dét. Ja, hvorfor ikke unne deg et par timers høytid – hver uke? Velkommen til Oslo-Filharmoniens 98. sesong! Ingrid Røynesdal Administrende direktør 3 Star Wars S. 27 Vi feirer filmhistoriens mektigste og mest berømte lydspor live og med fullt symfoniorkester.