Bram Fischer Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Suppression of Communism, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Instrumentality of Fear During Apartheid

THE SUPPRESSION OF COMMUNISM, THE DUTCH REFORMED CHURCH, AND THE INSTRUMENTALITY OF FEAR DURING APARTHEID. SAMUEL LONGFORD: 3419365 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR PARTICIA HAYES i A mini-thesis submitted for the degree of MA in History University of the Western Cape November 2016. Supervisor: Professor Patricia Hayes DECLARATION I declare that The Suppression of Communism, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Instrumentality of Fear during apartheid is my own work and has not been submitted for any degree or examination in any other university. All the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by complete references. NAME: Samuel Longford: 3419365 DATE: 11/11/2016. Signed: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. This mini-thesis has been carried out in concurrence with a M.A. Fellowship at the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR), University of the Western Cape (UWC). I acknowledge and thank the CHR for providing the funding that made this research possible. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CHR. Great thanks and acknowledgement also goes to my supervisor, Prof Patricia Hayes, who guided me through the complicated issues surrounding this subject matter, my partner Charlene, who put up with the late nights and uneventful weekends, and various others who contributed to the workings and re-workings of this mini-thesis. iii The experience of what we have of our lives from within, the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves in order to account for what we are doing, is fundamentally a lie – the truth lies outside, in what we do.1 1 Slavoj Zizek¸ Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (London: Profile Books, 2008): 40. -

2O PRICE South Africa and High Commission Territories

a. A a. A SBmmmmo S a 0, SA 3ao-&?2o PRICE South Africa and High Commission Territories: 10 cents. Elsewhere in Africa: Is. All other countries, Is. 6d, or equivalent in local currency ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (4 ISSUES) Africa, 40 cents (or 4s.) post free. All other countries, 6s. (U.S. $1) or equivalent. Airmail, 15s. (U.S., $2.50) AGENTS Usual trade discount (one-third of retail price) to bookshops and sellers ordering 12 or more copies EDITORIAL Articles, letters, material for articles and comment are invited on all themes of African interest, but payment is by prior arrangement only ADDRESS All letters, subscriptions and other correspondence must be sent to the distributor: Ellis Bowles, 52 Palmerston Road, London, S.W.14, England THE AFRICAN COMMUNIST Published quarterly in the interests of African solidarity, gxd as a forum for Marxist-Leninist thought throughout our Continent, by the South African Communist Party No 22 Third Quarter 1965 Contents S THE SOUTH AFRICAN PEOPLE WILL WIN THEIR FREEDOM! CENTRAL COMMITTEE, SOUTH AFRICAN COMMUNIST PARTY 13 EDITORIAL NOTES THE PLEDGE IS BINDING No EASY WALK ALGERIAN EVENTS 23 EAST AFRICAN TRENDS KENYA 'AFRICAN SOCIALISM' PAPER Sol Dubula TANZANIA FIVE YEAR PLANS A. Langa 46 THE 'FISCHER' TRIAL Z. Nkosi 56 AFRICA NOTES ON CURRENT EVENTS 61 WALLACE-JOHNSON-A TRIBUTE Bankole Akpata 65 AFRICA AND DEMOCRACY-A DISCUSSION Alex Chima A. Chukuka Eke 75 FACTS ON ANGOLA ANGOLAN STUDY CENTRE 85 BOOK REVIEWS Jack Cohen, Peter Mackintosh, F. Azad. 101 DOCUMENTS RALLY AND UNITE ANTI-IMPERIALIST FORCES THE SOUTH AFRICAN PEOPLE WILL WIN THEIR FREEDOM ! A Statement by the Central Committee of the South African Communist Party Although the key to the liberation of South Africa is in reorganization and intensification of revolutionary struggle inside the country, the freedom-loving people of South Africa deeply value and set great store on supporting solidarity actions, especially those which can cut off the Verwoerd regime from its economic and military bases in the imperialist countries. -

Ss That He Is an Accomplice

«*> 209. HLAPANE. BARTHOLOMEU MORU HLAPANE, (s.s.) BY THE COURT:Tell the witness that he is an accomplice. He is bound to answer questions which might incriminate him, but if he answers all questions to the satisfaction of the Court, the Court has the right to declare him immune from prosecution. Such a finding then is binding on the Prosecution. EXAMINATION BY STATE PROSECUTOR: You are at present a detainee under the lQO day Clause? --- That is correct, your Worship. And were you a member of the South African Commu nist Party? --- Yes, your Worship. When did you become a member? -- During the year 1955. At whose instigation? --- Joe Slovo. And were you placed in a cell? ---- That is correct. With Whites or non-Whites? ---- Non-Whites. And how long did you remain in'this cell? --- From the year 1955 to 1959 And what happened then? --- I was then transferred to the area committee. Also in the townships? ---- That is correct, your Worship. Did you serve on the area for some years? ---- Until 1961. What happened to you then? --- I was then placed on the district committee. Was the district committee a higher body than the area committee? --- That is so, yes, your Worship. And when you were placed on the district committee, were you assigned any special duties? Yes 210. HLAPANE What was that? ---- I was then full time organiser of the district committee. What did that work involve? --- To watch the area committees, if they were functioning properly, and also the cells. Did you have any duties in regard to recruiting members?---- That is so. -

("ARM"), 1960- 1964 Sabotage and the Question of the Ideological Subject Andries Du Toit Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the M.A

The National Committee for The National Committee for Liberation ("ARM"), 1960- 1964 Sabotage and the Question of the Ideological Subject Andries du Toit Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the M.A. degree in History at the University of Cape Town For my Parents "All of us are living and thinking subjects. What I react against is the fact that there is a breach between social history and the history of ideas. Social historians are supposed to describe how people act without thinking, and historians of ideas are supposed to describe how people think without acting. Everybody both thinks and acts." Michel Foucault "To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it 'the way it really was' (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger." Walter Benjamin Abstract Title The National Committee for Liberation ("ARM") 1960 - 1964: sabotage and the question of the ideological subject. Subject Matter The dissertation gives an account of the history of the National Committee for Liberation (NCL), an anti- apartheid sabotage organisation that existed between 1960 and 1964. The study is aimed both at narrating its growth and development in the context of South Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, and explaining its strategic and political choices. In particular, the reasons for its isolation from the broader struggle against Apartheid and its inability to transcend this isolation are investigated. Sources Discussion of the context of the NCL's development depended on secondary historical works by scholars such as Tom Lodge, Paul Rich, C. -

Jrýk, Msolkw Olm. Oo R. Mix~ P 4 La Going W, 11 Ill M Ii

wo wo 21 ~ ;k!, . .... .... Yt W:j . 2: mamew~ ,jrýk, msolkw Olm. oo r. mix~ p 4 la going W, 11 ill M Ii. immel hell .1m"dmgdmgdmdwmawaw . ... ... ...... ..... im ljniffi alibi: Nwalm, Offi . ..... Offi Offi 1160.1 00 i Wi 001.1 Ni .......... iw ........... .... ~New~ .1mall 0 111 all . ........ ....... AP AÅL- A SURVEY OF RACE RELATIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA 1964 Compiled by MURIEL HORRELL Research Officer South African Institute of Race Relations SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS P.O. Box 97 JOHANNESBURG 1965 ACKNOWLEDGEM ENTS Again Dr. Ellen Hellmann checked the manuscript of this Survey, made invaluable suggestions for its improvement, contributed material to fill various gaps, and gave constant encouragement. Dr. Hellmann's help was appreciated more than ever this year because the writer had been overseas for five months and out of close touch with the South African scene. During this period Miss Mary Draper of the Institute's staff spent a great deal of time collecting material for the Survey, analysing legislation, and summarizing official documents. She was assisted by Miss Lesley Cawood and Miss Brenda Adams. Very sincere appreciation is expressed to them for their contributions. Mr. Quintin Whyte and Mr. F. J. van Wyk kindly checked certain sections of the manuscript. Mr. Stanley Osler generously allowed the writer to make use of educational material he had obtained. Numerous Government and Provincial Departments furnished information. The writer is indebted, too, to Mrs. Merle Stoltenkamp and Mrs. M. Dickson, who did the typing; to Mr. L. Hotz and Mrs. A. Honeywill, who saw the manuscript through the Press; to the staff of the Institute's library; and to the printers, The Natal Witness (Pty.) Ltd. -

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Sixteen On Trial State versus Abram Fischer and Thirteen Others The change from being a 90-day detainee under solitary confinement to an awaiting trial prisoner was bewildering and the transition unexpectedly confusing. In “solitary” I was unable to communicate with family, fellow-detainees or legal counsel, write letters or talk! As an awaiting trial prisoner I could “enjoy” all these facilities but the effects of solitary detention lingered. Fear of further interrogation and solitary confinement left me wary of everything connected with the police and prisons and the prolonged imposition of silence was contrasted by an endless need to talk. I remained in solitary confinement from the first week in July 1964 until the third week in August, approximately 54 days after my arrest on 3 July. After being charged with membership of the South African Communist Party and furthering the aims of Communism, I was held with the other male detainees at the old Fort in Johannesburg.1 Our cells in the men’s section of the prison were constructed of steel, painted a dark gray, with lighter metal inner gates twisted in the shape of chicken wire. At night the “cages” were closed by a heavier metal outer door, but although the ambiance was chaotic, noisy and disorganized, it was a complete antidote to the silence we had experienced under solitary confinement. A part of the section still stands in the grounds of the Constitutional Court in Johannesburg, where the Fort once stood, probably viewed today by visitors as a quaint relic of the old regime. -

Published by the Anti-Apartheid Movement June 1965 Number 5

Published by the Anti-ApartheidMovement June1965 number5 pricesixpence Published by the Anti-ApartheidMovement June1965 number5 pricesixpence Uy Emi and the White i problem David Enhals, MP, write s The prssure for the British GoI ment to act to warn would-be emigrants to South Africa of ch conditions which exist ther is ing. At the end of May the na conference of the United Natio Association passed i resolution on the Government actively to dcourage emigration to South The flow of emigrants hrn Bn. und the assited passaec sehe s steadily increasing (12,612 we vearl and the determinatio o tile Verwoerd Goverment to step up the tempo a wn by the lavish advertising campaign i recent week They are especially anxious to tMp skilled workers and telhnicians. When the TSR-2 project was cancelled South A rceived a diately ook steps pt ira i facingredundancytotakejobsin S the South African aircraft industry They claimed that more than et00 applications had been received aind o testhat500hauslmctedimmigrahe tees neito demonrate form.....dappliedforjobs. neonn andn part coner asteteaa t togIt llh an eneas a good wayof doing it. Mostofthosenowsigningtheo 0ultimateluutworrkablitise Afr oulat ia ont w hbouriS Thirdly, parties might ulk to .ei h rider haveouth b frin b don't the w hatkie to , its a lutiton a tern stathe position of the High Commission theyloe andta- if hey ei t Thoughthelidmaybetight futum n territories. If on o.be demonstrate fstecraritydeeaisthtaioa themonthwienindpiclearlythatapartheid is wrong and wag es.. Bt athey re eo thatndb too greatand there wiflbe an conference' ulmatey ... ..kable it i s essen.ti ll agescan outio he epeneo to o explosion. -

Ntate Andrew Mokete Moeti Mlangeni

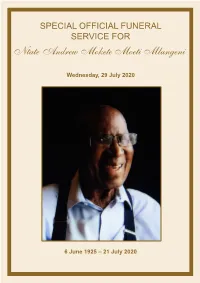

SPECIAL OFFICIAL FUNERAL SERVICE FOR Ntate Andrew Mokete Moeti Mlangeni Wednesday, 29 July 2020 6 June 1925 – 21 July 2020 Obituary of Ntate Andrew Mokete Moeti Mlangeni Upbringing Ntate Andrew Mokete Moeti Mlangeni was born on 6 June 1925 in Matoding (later renamed Maynhartfontein farm) outside Bethlehem in the then Boer Republic of Orange Free State (now Free State Province). He is the ninth of 12 children of Ntate Matia and Mama Aletta Mlangeni, and belonged to one of the three sets of twins by the couple. His parents were farm labour tenants. His father passed on when he was six years old and he was brought up by his mother, with the assistance of his elder brothers. In 1934 his family moved from the farm to rented accommodation in Bethlehem. He moved with his mother to Johannesburg in 1941. In Johannesburg, Ntate Mlangeni stayed with his elder brother, Sekila, in Pimville, Soweto and later at a makeshift settlement in present-day Orlando township before he found his current house in Dube in 1954, which became his home until his death. He met June Johanna Ledwaba in 1948 and they married in 1950. They were blessed with four children – two girls, Maureen and Sylvia, and two boys, Sello and Aubrey, who has since passed on. Education He started school at the age of 11 in Bethlehem when he enrolled himself at a local church-run school and passed Standard 4 in 1941. He later enrolled for Standard 5 at Pimville Government School in 1942 and passed Standard 6 in 1943. -

Conditions and Resistance of Women in Apartheid South Africa

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES ^For their triumphs and for their teafS WOMEN IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA HILDA BERNSTEIN pn International Defence and Aid Fund l&J Price 50p Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/fortheirtriumphsOObern FOR THEIR TRIUMPHS AND FOR THEIR TEARS Conditions and Resistance of Women in Apartheid South Africa by Hilda Bernstein Remember all our women in thejails Remember all our women in campaigns Remember all our women over manyfighting years Remember all our womenfor their triumphs, andfor their tears (from 'Women's Day Song') INTERNATIONAL DEFENSE & AID FOND for Southern Africa P.O. BOX 17 CAMBRIDGE, MA. 02138 m International Defence & Aid Fund 104 Newgate Street EC1 August 1975 ISBN 904759 06 7 CONTENTS An explanation and some essential information Part One : THE FRAMEWORK 1. Women under Apartheid 2. Migrant Labour 3. Forced Removals Part Two: THE CONDITIONS 4. Women in the Reserves 18 5. Women in the Towns 25 6. Family Life 29 7. Women at Work ... 36 Illustrations following page 32 Part Three: RESISTANCE 8. Women in the Political Struggle 40 9. The Struggle Continues 50 10. Looking Forward 56 Brief Biographies 61 Illustrations following page 64 Appendix 66 Women who have been imprisoned, banned, etc. for their opposition to apartheid 69 References 72 An Explanation and Some Essential Information The language of apartheid is a totally necessary part of its ideology. Without the special words and phrases that have been created, the ideology would disappear, because it is not a theory constructed on the basis of reason, but an expedient ieveloped to disguise the truth and erected on the basis of a special language. -

Hitler's Typewriter Released from SA Bank Vault

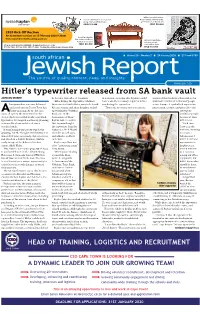

William Joseph Kentridge, Chester Silver 4-piece tea set, maker Notes Towards A Model Opera, George Nathan & Ridley Hayes giclee print on archival paper SOLD R12,000 SOLD R30,000 2020 Kick-Of Auction Art & antiques auction on 15 February 2020 9:30am Mont Blanc Agatha Items wanted for forthcoming auctions Christie limited edition Victorian 2-tier bufet fountain pen, boxed with pierced and View upcoming auction highlights at www.rkauctioneers.co.za SOLD R13,000 carved foliate back 011 789 7422 • 011 326 3515 • 083 675 8468 • 12 Allan Road, Bordeaux, Johannesburg SOLD R15,000 south african n Volume 24 – Number 2 n 24 January 2020 n 27 Tevet 5780 The source of quality content, news and insights t www.sajr.co.za Hitler’s typewriter released from SA bank vault JORDAN MOSHE he became chancellor of Germany. in question, stressing that Snyman would as part of the machinery that lead to the “After buying the typewriter, Matzner have made the necessary enquiries before systematic murder of millions of people heavy wooden crate was delivered then came to South Africa, married a South purchasing the typewriter. across Europe. It symbolised oppression, and pried open in Forest Town last African woman, and their daughter ended “There was no reason not to accept its persecution, torture, and genocide – the Friday morning. As the lid came up working for Volkskas attempt to away,A all eyes in the room fixed on the Bank, one of the annihilate people, object which sat nestled inside: a jet-black forerunners of Absa,” because of their typewriter, its complex machinery gleaming Bayliss says. -

JEWISH AFFAIRS, the SA Jewish Board of Deputies Aims to Produce a Cultural Forum Which Caters for a Wide Variety of Interests in the Community

1 MISSION In publishing JEWISH AFFAIRS, the SA Jewish Board of Deputies aims to produce a cultural forum which caters for a wide variety of interests in the community. JEWISH AFFAIRS aims to publish essays of scholarly research on all subjects of Jewish interest, with special emphasis on aspects of South African Jewish life and thought. It will promote Jewish cultural and creative achievement in South Africa, and consider Jewish traditions and heritage within the modern context. It aims to provide future researchers with a window on the community’s reaction to societal challenges. In this way the journal hopes critically to explore, and honestly to confront, problems facing the Jewish community both in South Africa and abroad, by examining national and international affairs and their impact on South Africa. In keeping with the provisions of the National Constitutional, the freedom of speech exercised in this journal will exclude the dissemination of the propaganda, personal attacks or invective, or any material which may be regarded as defamatory or malicious. In all such matters, the Editor’s decision is final. EDITORIAL BOARD EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Saks SA Jewish Board of Deputies ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD Suzanne Belling Author and Journalist Dr Louise Bethlehem Hebrew University of Jerusalem Marlene Bethlehem SA Jewish Board of Deputies Cedric Ginsberg University of South Africa Professor Marcia Leveson Naomi Musiker Archivist and Bibliographer Gwynne Schrire SA Jewish Board of Deputies Dr Gabriel A Sivan World Jewish Bible Centre Professor Gideon Shimoni Hebrew University of Jerusalem Professor Milton Shain University of Cape Town The Hon. Mr Justice Ralph Zulman © South African Jewish Board of Deputies Permission to reprint material from JEWISH AFFAIRS should be applied for from The South African Jewish Board of Deputies Original, unpublished essays of between 1000 and 5000 words are invited, and should be sent to: The Editor, [email protected] 2 JEWISH AFFAIRS Vol. -

Sechaba, Vol. 24, No. 9

Sechaba, Vol. 24, No. 9 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 38 Alternative title Sechaba Author/Creator African National Congress (Lusaka, Zambia) Publisher African National Congress (Lusaka, Zambia) Date 1990-09 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1990 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Rights By kind permission of the African National Congress (ANC). Format extent 36 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 38 SECHABASEPTEMBER 1990official organ of the african national