AN EXAMINATION of the CELWYDD GOLAU Presented For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Letters to the Reverend Elias Owen, (NLW MS 12645C.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 08, 2017 Printed: May 08, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/letters-to-reverend-elias-owen archives.library .wales/index.php/letters-to-reverend-elias-owen Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Letters to the Reverend Elias Owen, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 5 - Tudalen | Page 2 - NLW MS 12645C. Letters to the Reverend Elias Owen, Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information -

Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Thomas Edward Ellis Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 4 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pwyntiau -

Hysbysebwch Yn Pethe Penllyn

CYFRES NEWYDD: 287 Pris: 60c MAI 2021 Cynnal traddodiad ... YN Y RHIFYN HWN 2 Cynnal Traddodiad/Clwb 200 3 'Beic amdani!' gynulleidfa yn canu emyn Huw Derfel, ‘Y Gŵr a fu gynt 4 'Yma ac acw o'r Sarnau' [EP] o dan hoelion ...’ yn nyddiau hen bafiliwn Llandderfel 5 Cyrraedd 1m cyn 2050? a godwyd ym 1927. Disgwylir y bydd Eisteddfod 6 Y Gornel Greadigol [GE] Llandderfel, un o wyliau pwysig y Llannau, ynghyd â 7 Garddio Gwyrdd [R]/Rysáit y mis Y Llanuwchllyn a Llanfachreth (Llangwm, yn anffodus, 8 Cofeb Bob Tai'r Felin wedi darfod bellach) yn dal ei thir pan ddaw bywyd yn 9 Cofio Carys Puw Williams ôl i ryw fath o drefn. Bydd wynebau rhai o'r gynulleidfa'n 10 'Canmolwn ...' Huw Cae Llwyd gyfarwydd, mae'n siŵr. Pwy oedd y delynores, tybed ... 11 [yn parhau] 12 Taith Edward Llwyd neu'r arweinydd? Rydym ni'n tybio mai un o ’steddfodau'r 13 Gwaith pren cerfiedig 1950au sydd yma. Yden ni'n iawn? Rhowch wybod. 14 Yr Urdd/ Cymrorth Cristnogol Er gwaethaf y cyfnod clo eleni, aethpwyd ati i gynnal 15 Teyrnged i Pat Jones, Llandderfel y traddodiad yma ... yn rhithiol, gan rai o drigolion 16 Llun cynnar o'r Bala / Croesair 287 Llandderfel. Darllenwch yr hanes ar dudalen 2. PETHE MEHEFIN ERTHYGLAU YNG NGOFAL CLWB 200 TÎM golygyDDOL COFIWCH LLANDRILLO Mae enwau Gellir gweld PETHE PENLLYN ar-lein erbyn i’w cyflwyno erbyn hyn. Cliciwch ar y ddolen yma i gael mynediad enillwyr Mai 10fed o Fai i'r safle perthnasol: Ar werth o'r 30ain o Ebrill bro.360.cymru/papurau-bro ar dudalen 2 PETHE PENLLYN–RHIFYN 287–MAI 2021 TÎM GolygyDDOL LLANDDERFEL FU’N GYFRIFOL AM GASGLU’R Cadw Traddodiad ERTHYGLAU A’R LLUNIAU AR GYFER Y RHIFYN HWN r gwaetha’r COVID19 a’r ffaith am yr ail waith yn olynol nad oedd Eisteddfod y Groglith yn cael ei chynnal yn Llandderfel eleni, mi lwyddwyd i gadw un traddodiad pwysig sy’n berthnasol iawn i Landderfel ac i’r Eisteddfod, sef SWYDDOGION: canu emyn Huw Derfel – y Cyfamod Disigl a hynny yn rithiol. -

Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, (GB 0210 ROBEVS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors- records-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors-records-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 5 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Welsh Folk-Lore Is Almost Inexhaustible, and in These Pages the Writer Treats of Only One Branch of Popular Superstitions

: CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Library Cornell UnlverBlty GR150 .095 welsh folMore: a co^^^^ 3 1924 029 911 520 olin Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029911520 : Welsh Folk=Lore T A COI/LEGTION OF THE FOLK-TALES AND LEGENDS OF NOKTH WALES Efffl BEING THB PRIZE ESSAY OP THE NATIONAL EISTEDDFOD, 1887, BT THE Rev. ELIA.S QWEN, M.A., F.S.A. REVISED AND ENLARGED BY THE AUTHOR. OSWESTRY AND WREXHAM ; PRINTED AND PITBLISHKD BY WOODALL, MIKSHALL, AND 00. PREFACE. To this Essay on the " Folk-lore of North Wales," was awarded the first prize at the Welsh National Eisteddfod, held in London, in 1887. The prize consisted of a silver medal, and £20. The adjudicators were Canon Silvan Evans, Professor Rhys, and Mr Egerton PhiHimore, editor of the Gymmrodor. By an arrangement with the Eisteddfod Committee, the work became the property of the pubHshers, Messrs. Woodall, Minshall, & Co., who, at the request of the author, entrusted it to him for revision, and the present Volume is the result of his labours. Before undertaking the publishing of the work, it was necessary to obtain a sufficient number of subscribers to secure the publishers from loss. Upwards of two hundred ladies and gentlemen gave their names to the author, and the work of pubhcation was commenced. -

Chapter VIII Witchcraft As Ma/Efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, the Third Phase of the Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft

251. Chapter VIII Witchcraft as Ma/efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, The Third Phase of The Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases were concerned specifically with the practice of witchcraft, cases in which a woman was brought to court charged with being a witch, accused of practising rna/efice or premeditated harm. The woman was not bringing a slander case against another. She herself was being brought to court by others who were accusing her of being a witch. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in early modem Wales were completely different from those witchcraft as words cases lodged in the Courts of Great Sessions, even though they were often in the same county, at a similar time and heard before the same justices of the peace. The main purpose of this chapter is to present case studies of witchcraft as ma/efice trials from the various court circuits in Wales. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in Wales reflect the general type of early modern witchcraft cases found in other areas of Britain, Europe and America, those with which witchcraft historiography is largely concerned. The few Welsh cases are the only cases where a woman was being accused of witchcraft practices. Given the profound belief system surrounding witches and witchcraft in early modern Wales, the minute number of these cases raises some interesting historical questions about attitudes to witches and ways of dealing with witchcraft. The records of the Courts of Great Sessions1 for Wales contain very few witchcraft as rna/efice cases, sometimes only one per county. The actual number, however, does not detract from the importance of these cases in providing a greater understanding of witchcraft typology for early modern Wales. -

Celtic Folklore Welsh and Manx

CELTIC FOLKLORE WELSH AND MANX BY JOHN RHYS, M.A., D.LITT. HON. LL.D. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH PROFESSOR OF CELTIC PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, OXFORD VOLUME II OXFORD CLARENDON PRESS 1901 Page 1 Chapter VII TRIUMPHS OF THE WATER-WORLD Une des légendes les plus répandues en Bretagne est celle d’une prétendue ville d’ls, qui, à une époque inconnue, aurait été engloutie par la mer. On montre, à divers endroits de la côte, l’emplacement de cette cité fabuleuse, et les pecheurs vous en font d’étranges récits. Les jours de tempéte, assurent-ils, on voit, dans les creux des vagues, le sommet des fléches de ses églises; les jours de calme, on entend monter de l’abime Ie son de ses cloches, modulant l’hymne du jour.—RENAN. MORE than once in the last chapter was the subject of submersions and cataclysms brought before the reader, and it may be convenient to enumerate here the most remarkable cases, and to add one or two to their number, as well as to dwell at some- what greater length on some instances which may be said to have found their way into Welsh literature. He has already been told of the outburst of the Glasfryn Lake and Ffynnon Gywer, of Llyn Llech Owen and the Crymlyn, also of the drowning of Cantre’r Gwaelod; not to mention that one of my informants had something to say of the sub- mergence of Caer Arianrhod, a rock now visible only at low water between Celynnog Fawr and Dinas Dintte, on the coast of Arfon. -

Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire THE CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire R J Silvester, C H R Martin and S E Watson March 2014 Report for Cadw The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 www.cpat.org.uk © CPAT 2014 CPAT Report no. 1257 Historic Settlements in Denbighshire, 2014 An introduction............................................................................................................................ 2 A brief overview of Denbighshire’s historic settlements ............................................................ 6 Bettws Gwerfil Goch................................................................................................................... 8 Bodfari....................................................................................................................................... 11 Bryneglwys................................................................................................................................ 14 Carrog (Llansantffraid Glyn Dyfrdwy) .................................................................................... 16 Clocaenog.................................................................................................................................. 19 Corwen ...................................................................................................................................... 22 Cwm ......................................................................................................................................... -

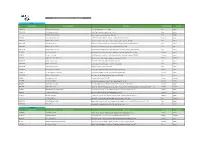

Permit Applications Determined - August 2017

Permit Applications Determined - August 2017 Waste Permit Number Permit Holder Name Site Address Type of Application Decision PAN-001718 ByProduct Recovery Limited Cefn Naw Clawdd Dolgellau LL40 2SG New Issued PAN-001730 Wales Environmental Ltd Dyffryn Farm Llangoedmor Llangoedmor SA43 2LS New Issued ByProduct Recovery Limited Cosmeston Farm Lavenock Rd Penarth CF64 5UP New Refused JB3593HA Coastal Oil And Gas Limited St. Nicholas Un-named Rd between the A4266 and Duffryn Duffryn CF5 6SU Surrender Issued PAN-001808 ByProduct Recovery Limited Great Pool Hall Great Pool Hall Llanvetherine Abergavenny Monmouthshire NP7 8NN New Issued PAN-001735 Whites Recycling Ltd Grosmont Wood Farm Grosmont Wood Farm Grosmont Abergavenny Monmouthshire NP7 8LB New Issued PAN-001795 ByProduct Recovery Limited Crossways Crossways Llanvapley Abergavenny Monmouthshire NP7 8SP New Issued PAN-001796 ByProduct Recovery Limited Emmasfield Farm Emmasfield Farm Llanddewi Rhydderch Abergavenny Monmouthshire NP7 8BP New Issued FP3894SZ Kier Services Limited Brynmenyn Civic Amenity Site Brynmenyn Ind Est Brynmenyn Bridgend Glamorgan CF32 9TQ Variation Issued FP3894LX Kier Services Limited Heol Ty Gwyn Civic Amenity Site Heol Ty Gwyn Ind Est Maesteg Bridgend Glamorgan CF34 0BQ Variation Issued AB3090CC Derwent Renewable Power Ltd Argoed Farm AD Facility Argoed Trefeglwys Caersws Powys SY17 5QT Transfer Withdrawn PAN-001738 ByProduct Recovery Ltd Hafod Farm Hafod Ferwig Cardigan Ceredigion SA43 1PU New Issued PAN-001790 ByProduct Recovery Ltd Llaethwryd Llaethwryd Cerrigydrudion Corwen Conwy LL21 0SF New Issued PAN-001729 Wales Environmental Ltd Rhydymaen Velindre Crymych SA41 3XH New Issued XB3393HM Project Red Recycling Limited Project Red Recycling Heol Creigiau Efail Isaf Pontypridd CF38 1BG Transfer Issued XB3393HM Tom Prichard Contracting Limited Project Red Recycling Heol Creigiau Efail Isaf Pontypridd CF38 1BG Variation Issued PAN-001745 ByProduct Recovery Limited Dros Y Mor Farm St. -

Denbighshire Record Office

GB 0209 DD/W Denbighshire Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 30234 The National Archives CLWYD RECORD OFFICE WREXHAM SOLICITORS' MSS. (Schedule of documen^sdeposited indefinite loan bvM Bff and Wrexham. 26 November 1976, 28 September 1977, 15 February 1980). (Ref: DD/W) Clwyd Record Office, 46, Clwyd Street, A.N. 376, 471, 699 RUTHIN December 1986 WREXHAM SOLICITORS MSS. CONTENTS A.N. 471 GROVE PARK SCHOOL, WREXHAM: Governors 1-5 General 6-56 Miscellaneous 57 65 ALICE PARRY'S PAPERS 66 74 DENBIGHSHIRE EDUCATION AUTHORITY 75 80 WREXHAM EDUCATION COMMITTEE 81-84 WREXHAM AREA DIVISIONAL EXECUTIVE 85 94 WREXHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL: Treasurer 95 99 Medical Officer's records 100 101 Byelaws 102 Electricity 103 - 108 Rating and valuation 109 - 112 Borough extension 113 - 120 Miscellaneous 121 - 140 WREXHAM RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL 140A DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL 141 142 CALVINISTIC METHODIST RECORDS: SeioSeionn CM.Chapel,, RegenRegentt StreeStreett 143 - 153 CapeCapell yy M.CM.C.. Adwy'Adwy'rr ClawdClawddd 154 - 155 Henaduriaeth Dwyrain Dinbych 156 - 161 Henaduriaeth Dyffryn Clwyd 162 - 164 Henaduriaeth Dyffryn Conwy 165 Cyfarfod misol Sir Fflint 166 North Wales Association of the 167 - 171 Presbyterian Church Cymdeithasfa chwaterol 172 - 173 Miscellaneous 174 - 180 PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF WALES: Lancashire, Cheshire, Flintshire and 181 - 184 Denbighshire Presbyterian Church Lancashire and Cheshire Presbytery 185 - 186 Cheshire, Denbighshire -

Lighting Plan

Exterior Lighting Master Plan Ver.05 -2015 Snowdonia National Park – Dark Sky Reserve External Lighting Master Plan Contents 1 Preamble 1.1.1 Introduction to Lighting Master Plans 1.1.2 Summary of Plan Policy Statements 1.2 Introduction to Snowdonia National Park 1.3 The Astronomers’ Point of View 1.4 Night Sky Quality Survey 1.5 Technical Lighting Data 1.6 Fully Shielded Concept Visualisation 2 Dark Sky Boundaries and Light Limitation Policy 2.1 Dark Sky Reserve - Core Zone Formation 2.2 Dark Sky Reserve - Core Zone Detail 2.3 Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E0's 2.4 Energy Saving Switching Regime (Time Limited) 2.5 Dark Sky Reserve – Buffer Zone 2.5.1 Critical Buffer Zone 2.5.2 Remainder of Buffer Zone 2.6 Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E1's 2.7 Environmental Zone Roadmap in Core and Critical Buffer Zones 2.8 External Zone – General 2.9 External Zone – Immediate Surrounds 3 Design and Planning Requirements 3.1 General 3.2 Design Stage 3.2.1 Typical Task Illuminance 3.2.2 Roadmap for Traffic and Residential Area lighting 3.3 Sports Lighting 3.4 Non-photometric Recipe method for domestic exterior lighting 4 Special Lighting Application Considerations 5 Existing Lighting 5.1 Lighting Audit – General 5.2 Recommended Changes 5.3 Sectional Compliance Summary 5.4 Public Lighting Audit 5.5 Luminaire Profiles 5.6 Public Lighting Inventory - Detail Synopsis Lighting Consultancy And Design Services Ltd Page - 1 - Rosemount House, Well Road, Moffat, DG10 9BT Tel: 01683 220 299 Exterior Lighting Master Plan Ver.05 -2015 APPENDICES -

FOLK-LORE and FOLK-STORIES of WALES the HISTORY of PEMBROKESHIRE by the Rev

i G-R so I FOLK-LORE AND FOLK-STORIES OF WALES THE HISTORY OF PEMBROKESHIRE By the Rev. JAMES PHILLIPS Demy 8vo», Cloth Gilt, Z2l6 net {by post i2(ii), Pembrokeshire, compared with some of the counties of Wales, has been fortunate in having a very considerable published literature, but as yet no history in moderate compass at a popular price has been issued. The present work will supply the need that has long been felt. WEST IRISH FOLK- TALES S> ROMANCES COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION By WILLIAM LARMINIE Crown 8vo., Roxburgh Gilt, lojC net (by post 10(1j). Cloth Gilt,3l6 net {by posi 3lio% In this work the tales were all written down in Irish, word for word, from the dictation of the narrators, whose name^ and localities are in every case given. The translation is closely literal. It is hoped' it will satisfy the most rigid requirements of the scientific Folk-lorist. INDIAN FOLK-TALES BEING SIDELIGHTS ON VILLAGE LIFE IN BILASPORE, CENTRAL PROVINCES By E. M. GORDON Second Edition, rez'ised. Cloth, 1/6 net (by post 1/9). " The Literary World says : A valuable contribution to Indian folk-lore. The volume is full of folk-lore and quaint and curious knowledge, and there is not a superfluous word in it." THE ANTIQUARY AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF THE PAST Edited by G. L. APPERSON, I.S.O. Price 6d, Monthly. 6/- per annum postfree, specimen copy sent post free, td. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. FOLK-LORE AND FOLK- STORIES OF WALES BY MARIE TREVELYAN Author of "Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character," " From Snowdon to the Sea," " The Land of Arthur," *' Britain's Greatness Foretold," &c.