The Faculty of Language: What's Special About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Has the Decline of Violence Reversed Since the Better Angels of Our Nature Was Written?

Has the Decline of Violence Reversed since The Better Angels of Our Nature was Written? Steven Pinker Many journalists, citing recent violence in Syria, Iraq, Gaza, and Ukraine, have asked me whether the decline of violence has gone into reverse since The Better Angels of Our Nature was written. The question betrays the same statistical misconceptions that led me to write Better Angels in the first place. People always think that violence has increased because they reason from memorable examples rather than from global data. If at any time you cherry-pick the most violent place in the world, then you’ll discover that yes, it’s violent. That has nothing to do with overall rates or trends in violence. The basic problem is that journalism is a systematically misleading way to understand the world. News is about things that happen, not about things that don’t happen. You never see a reporter standing on the streets of Angola, Sri Lanka, or Vietnam saying “I’m here reporting that a war has not broken out today.” It’s only by looking at data on the world as a whole that you get an accurate picture of the trends. Objectively, there has indeed been an uptick in war deaths in 2013 compared to 2012 (it’s too early to have data for 2014), mostly due to the war in Syria. But the overall level of deaths is still far below those of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, when the world was a far more dangerous place. Even putting aside the obvious examples (such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the 3- million-death war in Vietnam), one sees that the conflicts of today are far less damaging than those of past decades. -

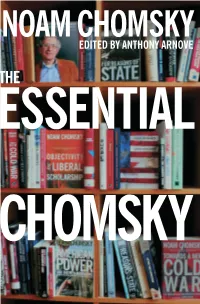

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

In Defense of Massive Modularity

3 In Defense of Massive Modularity Dan Sperber In October 1990, a psychologist, Susan Gelman, and three anthropolo- gists whose interest in cognition had been guided and encouraged by Jacques Mehler, Scott Atran, Larry Hirschfeld, and myself, organized a conference on “Cultural Knowledge and Domain Specificity” (see Hirsch- feld and Gelman, 1994). Jacques advised us in the preparation of the conference, and while we failed to convince him to write a paper, he did play a major role in the discussions. A main issue at stake was the degree to which cognitive development, everyday cognition, and cultural knowledge are based on dedicated do- main-specific mechanisms, as opposed to a domain-general intelligence and learning capacity. Thanks in particular to the work of developmental psychologists such as Susan Carey, Rochel Gelman, Susan Gelman, Frank Keil, Alan Leslie, Jacques Mehler, Elizabeth Spelke (who were all there), the issue of domain-specificity—which, of course, Noam Chomsky had been the first to raise—was becoming a central one in cognitive psychol- ogy. Evolutionary psychology, represented at the conference by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, was putting forward new arguments for seeing human cognition as involving mostly domain- or task-specific evolved adaptations. We were a few anthropologists, far from the main- stream of our discipline, who also saw domain-specific cognitive pro- cesses as both constraining and contributing to cultural development. Taking for granted that domain-specific dispositions are an important feature of human cognition, three questions arise: 1. To what extent are these domain-specific dispositions based on truly autonomous mental mechanisms or “modules,” as opposed to being 48 D. -

The Adaptive Significance of Human Language

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Senior Thesis Projects, 1993-2002 College Scholars 2000 The Adaptive Significance of Human Language Nathan Oesch Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_interstp2 Recommended Citation Oesch, Nathan, "The Adaptive Significance of Human Language" (2000). Senior Thesis Projects, 1993-2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_interstp2/52 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the College Scholars at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Thesis Projects, 1993-2002 by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Adaptive Significance of Human Language Nathan Oesch Department of Psychology University of Tennessee, Knoxville noesch @ utk. edu Abstract Many experts have argued that human language is fundamentally incompatible with the principles of traditional Darwinian evolutionary theory. According to conventional Darwinian explanations, specific traits evolved among species according to gradual and incremental genetic changes, each of which that were in some way so favorable to the survival and reproduction of ancestral generations that they were ultimately preserved within successive generations of those species. Human language, it has been said, is simply to complex to be explained as a result of Darwinian explanations, since each successive step in the evolution of language would confer no obvious survival benefits to its recipients. According to this idea, language is such an "all-or none system," that it could not possibly have existed in any immediately beneficial intermediate forms and thus could not have evolved according to conventional Darwinian modes of explanation. -

Balanced Biosocial Theory for the Social Sciences

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2004 Balanced biosocial theory for the social sciences Michael A Restivo University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Restivo, Michael A, "Balanced biosocial theory for the social sciences" (2004). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1635. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/5jp5-vy39 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALANCED BIOSOCIAL THEORY FOR THE SOCIAL SCIENCES by Michael A. Restivo Bachelor of Arts IPIoridkijSjlarrhcIJiuAHsrsity 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillm ent ofdœnxpnnnnenkfbrthe Master of Arts Degree in Sociology Departm ent of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas M ay 2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1422154 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Throughout His Career, Whether Studying Language

Throughout his career, whether studying language, advocating a realistic biology of mind, or examining the human condition through the lens of humanistic Enlightenment ideas, psychologist Steven Pinker has embraced and championed a naturalistic understanding of the universe and the computational theory of mind. He is perhaps the first internationally recognized public intellectual whose recognition is based on the advocacy of empirically based thinking about language, mind, and human nature. “Just as Darwin made it possible for a thoughtful observer of the natural world to do without creationism,” he says, “Turing and others made it possible for a thoughtful observer of the cognitive world to do without spiritualism.” In the debate about AI risk, he argues against prophecies of doom and gloom, noting that they spring from the worst of our psychological biases—exemplified particularly by media reports: “Disaster scenarios are cheap to play out in the probability-free zone of our imaginations, and they can always find a worried, technophobic, or morbidly fascinated audience.” Hence, over the centuries: Pandora, Faust, the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Frankenstein, the population bomb, resource depletion, HAL, suitcase nukes, the Y2K bug, and engulfment by nanotechnological grey goo. “A characteristic of AI dystopias,” he points out, “is that they project a parochial alpha-male psychology onto the concept of intelligence. History does turn up the occasional megalomaniacal despot or psychopathic serial killer, but these are products of a history of natural selection shaping testosterone-sensitive circuits in a certain species of primate, not an inevitable feature of intelligent systems.” In the present essay, he applauds Wiener’s belief in the strength of ideas vis-à-vis the encroachment of technology. -

The Strange Survival and Apparent Resurgence of Sociobiology

This is a repository copy of The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118157/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Dennis, A. orcid.org/0000-0003-4625-1123 (2018) The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. History of the Human Sciences, 31 (1). pp. 19-35. ISSN 0952- 6951 https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695117735966 Dennis A. The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. History of the Human Sciences. 2018;31(1):19-35. Copyright © 2017 The Author(s). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695117735966. Article available under the terms of the CC- BY-NC-ND licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology Abstract A recent dispute between Richard Dawkins and Edward O. Wilson concerning fundamental concepts in sociobiology is examined. -

Redundancy As a Phonological Feature in the English Language

International Journal of English Language and Communication Studies Vol. 4 No.2 2018 ISSN 2545 - 5702 www.iiardpub.org Redundancy as a Phonological Feature in the English Language Shehu Muhammed Department of GSE School of Education Aminu Saleh College of Education, Azare, Bauchi State Nigeria [email protected] Msuega Ahar Department of Languages and Linguistics, Benue State University, Makurdi [email protected] Daniel Benjamin Saanyol Department of Psychology, School of Education, Aminu Saleh College of Education Azare, Bauchi State [email protected] Abstract The study critically examines redundancy as a phonological feature in the English Language. It establishes that it is an integral aspect of the English phonology. The study adopts a survey method using structuralist approach. The study was conducted among the speakers of English language in Benue State University, Makurdi. The sample size of about 60 respondents were taken from a selected number of departments: Languages and linguistics, Mass communication, Religion and Philosophy, Theatre Arts, English language and the Political Science undergraduate students who ranged from 16 - 35 years. The study used the following instruments: oral interviews, personal observations and discussion group to obtain data for the study. The findings reveal that redundancy must be understood and given space in the daily practice of the language. This will enhance effective communication and understanding among speaker of English Language. In fact, failure in speaking the language with a consistent agreement to the entire phonological system (including the redundant features) will sometimes amount to communication breakdown and misinterpretation of the meaning. A close observation has shown that many speakers of English language lack a good knowledge of its phonological system. -

The Idea of Universality in Linguistics and Human Rights

The Idea of Universality in Linguistics and Human Rights SPEAKER: Noam Chomsky Institute Professor; Professor of Linguistics SPEAKER: Elizabeth S. Spelke Professor of Psychology Co- Director, Mind, Brain, and Behavior Inter-faculty Initiative, Harvard University. The Idea of SPEAKERS: Universality in Noam Chomsky: Institute Professor; Professor of Linguistics Linguistics and Human Rights Elizabeth S. Spelke: Professor of Psychology Co-Director, Noam Chomsky Mind, Brain, and Behavior Inter-faculty Initiative, Harvard March 15,2005 University. Time 00:57:13 ABOUT THE LECTURE: If humans have a common, in-born capacity for language, and Audio Only: for such complex behaviors as morality, might the faculties be QuickTime – 28MB somehow linked? Noam Chomsky perceives a mere thread of MP3 - 70MB a connection. At breakneck speed, Chomsky leads us through Audio and Video: a history of language theory, concluding with the revolutionary QuickTime - 371MB model he championed: a universal grammar underpinning all WindowsMedia - 313MB languages that corresponds to an innate capacity of the human RealVideo - 101MB brain. While scientists may now have a “clearer grasp of the universals of language,” says Chomsky, notions of universality grow murky as we move “into domains of will, choice and judgment.” Chomsky cites the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights as one example of “broad cross-cultural consensus.” But he brandishes examples of how “our moral and intellectual culture….forcefully rejects universal moral judgments” -- such as continued U.S. -

Report Concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein's Connections to Harvard University

REPORT CONCERNING JEFFREY E. EPSTEIN’S CONNECTIONS TO HARVARD UNIVERSITY Diane E. Lopez, Harvard University Vice President and General Counsel Ara B. Gershengorn, Harvard University Attorney Martin F. Murphy, Foley Hoag LLP May 2020 1 INTRODUCTION On September 12, 2019, Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow issued a message to the Harvard Community concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein’s relationship with Harvard. That message condemned Epstein’s crimes as “utterly abhorrent . repulsive and reprehensible” and expressed “profound[] regret” about “Harvard’s past association with him.” President Bacow’s message announced that he had asked for a review of Epstein’s donations to Harvard. In that communication, President Bacow noted that a preliminary review indicated that Harvard did not accept gifts from Epstein after his 2008 conviction, and this report confirms that as a finding. Lastly, President Bacow also noted Epstein’s appointment as a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Psychology in 2005 and asked that the review address how that appointment had come about. Following up on President Bacow’s announcement, Vice President and General Counsel Diane E. Lopez engaged outside counsel, Martin F. Murphy of Foley Hoag, to work with the Office of General Counsel to conduct the review. Ms. Lopez also issued a message to the community provid- ing two ways for individuals to come forward with information or concerns about Epstein’s ties to Harvard: anonymously through Harvard’s compliance hotline and with attribution to an email ac- count established for that purpose. Since September, we have interviewed more than 40 individu- als, including senior leaders of the University, staff in Harvard’s Office of Alumni Affairs and Development, faculty members, and others. -

The Language Instinct Steven Pinker June 18

The Language Instinct Steven Pinker June 18 - June 26, 2004 Mans uniqeuness in the universe has during recent history suffered many setbacks, the latest of them being the contention that not even his language ability sets him apart from his biological cousins - the Apes. Pinker easily debunks such claims as so much media- hype and wishful thinking. Clearly if the apes would have the potential for language, they would have discovered it and exploited it for their own purposes a long time ago. In fact in actual experiments deaf observers noted far fewer incidents of true handsigning then the more guillable normal-hearers, who charitably tended to interpret any movement of the hands as imbued with intentional symbolism. True, apes do communicate with each other, by sound as well as signs in the wild, but the purported incidents of language use, were invariably repetitive and shallow, no match to the sophistication of toddlers. Man learns to walk and talk without any explict instruction. So remarkable and so universal is the effortlessness of the acquisition that it is natural to consider it as instinctive. When it comes to locomotion such claims are uncontroversial, while when loquaciousness is concerned it is more disputable. Pinker presents as evidence for an innate language ability the phenomena of pidgin and creole. When people are thrown together with no common language, a pidgin inevitably emerges. This is a primitive and provisional language, using tidbits of vocabulary from ambient tongues pasted together using a rudimentary make- shift syntax. Young children exposed to pidgin instinctively make a real language out of it, imposing syntactic rules and thus rendering it expressive. -

How to Understand Conjugation in Japanese, Words That Form the Predicate, Such As Verbs and Adjectives, Change Form According to Their Meaning and Function

How to Understand Conjugation In Japanese, words that form the predicate, such as verbs and adjectives, change form according to their meaning and function. This change of word form is called conjugation, and words that change their forms are called conjugational words. Yōgen (用言: roughly verbs and adjectives) Complex Japanese predicates can be divided into several “words” when one looks at formal characteristics such as accent and breathing. (Here, a “word” is almost equivalent to an accent unit, or the smallest a unit governed by breathing pauses, and is larger than the word described in school grammar.) That is, the Japanese predicate does not consist of one word; rather it is a complex of yōgen, made up of a series of words. Each of the “words” that make up the predicate (i.e., yōgen complex) undergoes word form change, and words in a similar category may be strung together in a row. Therefore, altogether there is quite a wide variety of forms of predicates. Some people do not divide the yōgen complex into words, however. They treat the predicate as a single entity, and call the entire variety of changes conjugation. Some try to integrate all variety of such word form change into a single chart. This chart not only tends to be enormous in size, but also each word shows the same inflection cyclically. There is much redundancy in this approach. When dealing with Japanese, it will be much simpler if one separates the description of the order in which the components of the predicate (yōgen complex) appear and the description of the word form change of individual words.