The Future of the Federation T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Losing an Empire, Losing a Role?: the Commonwealth Vision, British Identity, and African Decolonization, 1959-1963

LOSING AN EMPIRE, LOSING A ROLE?: THE COMMONWEALTH VISION, BRITISH IDENTITY, AND AFRICAN DECOLONIZATION, 1959-1963 By Emily Lowrance-Floyd Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chairperson Dr. Victor Bailey . Dr. Katherine Clark . Dr. Dorice Williams Elliott . Dr. Elizabeth MacGonagle . Dr. Leslie Tuttle Date Defended: April 6, 2012 ii The Dissertation Committee for Emily Lowrance-Floyd certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: LOSING AN EMPIRE, LOSING A ROLE?: THE COMMONWEALTH VISION, BRITISH IDENTITY, AND AFRICAN DECOLONIZATION, 1959-1963 . Chairperson Dr. Victor Bailey Date approved: April 6, 2012 iii ABSTRACT Many observers of British national identity assume that decolonization presaged a crisis in the meaning of Britishness. The rise of the new imperial history, which contends Empire was central to Britishness, has only strengthened faith in this assumption, yet few historians have explored the actual connections between end of empire and British national identity. This project examines just this assumption by studying the final moments of decolonization in Africa between 1959 and 1963. Debates in the popular political culture and media demonstrate the extent to which British identity and meanings of Britishness on the world stage intertwined with the process of decolonization. A discursive tradition characterized as the “Whiggish vision,” in the words of historian Wm. Roger Louis, emerged most pronounced in this era. This vision, developed over the centuries of Britain imagining its Empire, posited that the British Empire was a benign, liberalizing force in the world and forecasted a teleology in which Empire would peacefully transform into a free, associative Commonwealth of Nations. -

British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55

School of History University of New South Wales Equivocal Empire: British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55 Daniel Kark A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales, Australia 2008 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. Date …………………………………………….............. For my parents, Vanessa and Adrian. For what you forfeited. Abstract This thesis resituates the Community Development programme as the key social intervention attempted by the British Colonial Office in Africa in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A preference for planning, growing confidence in metropolitan intervention, and the gradualist determination of Fabian socialist politicians and experts resulted in a programme that stressed modernity, progressive individualism, initiative, cooperative communities and a new type of responsible citizenship. Eventual self-rule would be well-served by this new contract between colonial administrations and African citizens. -

1TEWS NEWS Ffews HEWS from the South African Institute of Race Relations (Inc.) NUUS NUUS NUUS Van Die Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut Vir Rasseverhoudings (Ingelyf) NUUS

1TEWS NEWS ffEWS HEWS from the South African Institute of Race Relations (Inc.) NUUS NUUS NUUS van die Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut vir Rasseverhoudings (Ingelyf) NUUS P.O. Box 97 Johannesburg Poshus 97 RR.19/62 NOT TO BE RELEASED BEFORE 4 P.M. ON WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 17, 1962 CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE FEDERATION OF NYASALAND^ SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN RHODESIA. The refusal of a white minority to face the fact that Africa was rapidly ohanging, still less to keep in step with change, has always marked all constitutional advance in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The story of such constitutional advance has "been a tragic one of last-ditch heroics that real statesmanship would have foreseen, and avoided. This was the view taken hy Mr. Maurice Webb in delivering his well- reasoned and concise survey of constitutional developments in the territories concerned yesterday at the 1962 Council meeting of the S.A. Institute o± Race Relations in Port Elizabeth. Mr. Webb described Southern Rhodesia as the "coy lady of the Federation" in connection with her rejection of the proposed 1916'alliance w^Lth Northern Rhodesia and her subsequent rejection of the Union's advances in 1922. Only Northern Rhodesia's copper had finally weighted the scales in favour of her ultimate alliance. From the outset* Mr. Webb declared, the three territories* Nyasaland, Southern and Northern Rhodesia were "an ill-assorted menage", Southern Rhodesia was a British Crown Colony with responsible government, an all- White parliament and a very nearly a11-White electorate: Northern Rhodesia was a British Protectorate with a Legislative Council of a fractional more multi-racial character, made up of officials and nominated and eleoted members, with a White electorates Nyasaland, also a British Protectorate, had a Legislative Council of officials and nominated members, with no elected members or voters. -

EAP942: Preserving Nyasaland African Congress Historical Records

EAP942: Preserving Nyasaland African Congress historical records Mr Clement Mweso, National Archives of Malawi 2016 award - Pilot project £6,158 for 4 months Archival partner: National Archives of Malawi This pilot project surveyed Nyasaland African Congress records in selected districts in Malawi in order to assess the state of records, their storage conditions, and to determine the extent as well as their preservation needs. The project created this survey of holdings and digitised a small sample of these records. Further Information You can contact the EAP team at [email protected] ENDANGERED ARCHIVES PROGRAMME EAP 942 PRESERVING NYASALAND AFRICAN CONGRESS HISTORICAL RECORDS SURVEY REPORT ALEKE KADONAPHANI BANDA BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Aleke Kadonaphani Banda was born in 1939, was educated in Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia) and at the age of 14 in 1953, he ascended to the position of district secretary for Nyasaland African Congress in Que-Que, Zimbabwe. He returned to Malawi to join the Nyasaland African Congress and actively participated in the struggle for independence. When the Nyasaland African Congress was outlawed in 1959 due to the state of emergency, he was among a few congress politicians who were not in detention and he together with Kanyama Chiume and Orton Chirwa formed the Malawi Congress Party on 30th September 1959 to replace the now Banned Nyasaland African Congress. He served the MCP as its publicity secretary, secretary general and when other congress leaders were released from detention he became very close to Kamuzu Banda. In July 1960, he was part of the delegation to the Lancaster House Constitutional Conference in London, where the country’s first constitution was drafted. -

Rhodesia Accuses.Pdf

"In these pages I ask you — you people of the United Kingdom, you people of the older Dominions, you people of by the United States of America, you people of Europe — and the A.J.A. Peck respective governments of each one of you ... are you not, per haps, even as I write, now guilty ofj and contemplating yet, the perpetration of that final treason: the unconscious further ing of the ends of evil in the name of all that is most holy?" That is the question asked in this book. — Is it a question that the West can afford to ignore? A THREE SISTERS SPECIAL www.rhodesia.nl CONTENTS Preface Chapter 1. Introduction .. .. .. .. ... 7 2. A Letter to The Times 11 3. Reactions to "The Times" Letter .. .. 15 4. Ethical Insanity menaces Central Africa .. 19 5. The Good Faith of Mr. Macmillan's Govern ment 25 6. The Seeds of Bitterness: Rhodesia's 1961 Constitution 31 7. The "Sins" of the Rhodesians 52 8. The "Freedom" of African Nationalism .. 76 9. Todd and Whitehead 103 10. Ethical Insanity in Action 125 11. Thoughts concerning a Solution .. .. 144 12. Postscript .. 159 Appendix: The Middle Road—an Election Manifesto .. 165 PREFACE The letter reprinted here as Chapter 2 was origi nally published by The Times of London on the 19th November, 1965. It was reprinted in its entirety six days later by the East Africa and Rhodesia, a. weekly periodical published in London; it was quoted in The Rhodesia Herald, a Salisbury daily newspaper; and, after a further three weeks, it was re-published in full by a Salisbury weekly newspaper, The Citizen. -

Central Africa Editor PHILIP MURPHY Part I CLOSER

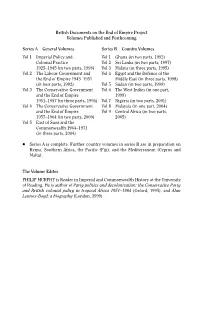

00-Central Africa-Blurb-cpp 7/10/05 6:53 AM Page 1 British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming Series A General Volumes Series B Country Volumes Vol 1 Imperial Policy and Vol 1 Ghana (in two parts, 1992) Colonial Practice Vol 2 Sri Lanka (in two parts, 1997) 1925–1945 (in two parts, 1996) Vol 3 Malaya (in three parts, 1995) Vol 2 The Labour Government and Vol 4 Egypt and the Defence of the the End of Empire 1945–1951 Middle East (in three parts, 1998) (in four parts, 1992) Vol 5 Sudan (in two parts, 1998) Vol 3 The Conservative Government Vol 6 The West Indies (in one part, and the End of Empire 1999) 1951–1957 (in three parts, 1994) Vol 7 Nigeria (in two parts, 2001) Vol 4 The Conservative Government Vol 8 Malaysia (in one part, 2004) and the End of Empire Vol 9 Central Africa (in two parts, 1957–1964 (in two parts, 2000) 2005) Vol 5 East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (in three parts, 2004) ● Series A is complete. Further country volumes in series B are in preparation on Kenya, Southern Africa, the Pacific (Fiji), and the Mediterranean (Cyprus and Malta). The Volume Editor PHILIP MURPHY is Reader in Imperial and Commonwealth History at the University of Reading. He is author of Party politics and decolonization: the Conservative Party and British colonial policy in tropical Africa 1951–1964 (Oxford, 1995), and Alan Lennox-Boyd: a biography (London, 1999) 01A-Map of Africa 7/10/05 6:56 AM Page 2 GABON R. -

Monckton and Cleopatra Patrick Keatley

63 MONCKTON AND CLEOPATRA PATRICK KEATLEY Commonwealth Correspondent of * The Guardian* WHEN Dr. Nkrumah and his friends use that evocative phrase, "the African Personality", I often wonder if they are including in their thoughts that most remarkable African of them all, Cleopatra. I thought of her myself, recently, in a rather odd context. I had just put down the 17^-page British Government Blue Book which bears the title "Report of the Advisory Commission on the Review of the Constitution of Rhodesia and Nyasaland." The world knows it simply as the Monckton Report. It has made world headlines; it is the basic working paper of the Federal Constitutional Review in London; it has produced —in the course of a couple of months—almost as many columns of comment as has the Queen of Egypt, in all her glory, down the centuries. There are other resemblances in the situation: we can only guess at the cost of Antony's expedition to Africa; but we know the cost of Walter Monckton's exactly. It is recorded in a careful footnote on page two (as we might expect of the chairman of one of Britain's largest banks) and it came to precisely £128,899. Certainly, in at least three respects Antony's African affair and the recent adventures of the Monckton Commissioners are remarkably the same. Both enterprises required Afro-European co-operation; in both cases Europeans came to learn much more than they had known previously about Africans and to respect them. And in both episodes, whether the onlookers approved or disapproved of what took place, it is a plain fact of history that the world could never afterwards be quite the same place again. -

Biographical Notes

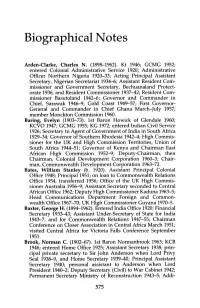

Biographical Notes Arden-Oarke, Charles N. (1898-1962). Kt 1946; GCMG 1952; entered Colonial Administrative Service 1920; Administrative Officer Northern Nigeria 1920-33; Acting Principal Assistant Secretary, Nigerian Secretariat 1934-6; Assistant Resident Com- missioner and Government Secretary, Bechuanaland Protect- orate 1936, and Resident Commissioner 1937-42; Resident Com- missioner Basutoland 1942-6; Governor and Commander in Chief, Sarawak 1946-9, Gold Coast 1949-57; First Governor- General and Commander in Chief Ghana March-July 1957; member Monckton Commission 1960. Baring, Evelyn (1903-73). 1st Baron Howick of Glendale 1960; KCVO 1947; GCMG 1955; KG 1972; entered Indian Civil Service 1926; Secretary to Agent of Government of India in South Africa 1929-34; Governor of Southern Rhodesia 1942-4; High Commis- sioner for the UK and High Commission Territories, Union of South Africa 1944-51; Governor of Kenya and Chairman East African High Commission 1952-9; Deputy-Chairman, then Chairman, Colonial Development Corporation 1960-3; Chair- man, Commonwealth Development Corporation 1963-72. Bates, William Stanley (b. 1920). Assistant Principal Colonial Office 1948; Principal 1951; on loan to Commonwealth Relations Office 1954, transferred 1956; Office of the UK High Commis- sioner Australia 1956-9; Assistant Secretary seconded to Central African Office 1962; Deputy High Commissioner Kaduna 1963-5; Head Communications Department Foreign and Common- wealth Office 1967-70; UK High Commissioner Guyana 1970-5. Baxter, George H. (1894-1962). Entered India Office 1920; Financial Secretary 1933-43; Assistant Under-Secretary of State for India 1943-7, and for Commonwealth Relations 1947-55; Chairman Conference on Closer Association in Central Africa March 1951; visited Central Africa for Victoria Falls Conference September 1951. -

Rhodesian UDI

Rhodesian UDI edited by Michael D. Kandiah ICBH Oral History Programme Rhodesian UDI The ICBH gratefully acknowledges the support of the Public Record Office and the Institute of Historical Research for this event ICBH Oral History Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2001 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS ISBN: 1 871348 70 6 Rhodesian UDI Held 6 September 2000 at the Public Record Office, London Chaired by Robert Holland Papers by Richard Coggins and Sue Onslow Seminars edited by Michael Kandiah Institute of Contemporary British History Contents List of Contributors 9 Citation Guidance 11 The British Government and Rhodesian UDI Richard Coggins 13 The Conservative Party and Rhodesian UDI Sue Onslow 23 Seminar Session I: Labour Government and Party 29 edited by Michael Kandiah Seminar Session II: Conservatives and UDI 49 edited by Michael Kandiah Commentary Colin Legum 69 Document: Unilateral Declaration of Independence 73 Chronology 75 Contributors Editor: MICHAEL D. KANDIAH Director of the Witness Seminar Programme, Institute of Contemporary British History Session 1 Labour Government and Party Chair: ROBERT HOLLAND Institute of Commonwealth Studies Paper-giver: RICHARD COGGINS The Queen’s College, Oxford Witnesses: GEORGE CUNNINGHAM Commonwealth Relations Office 1956-63. -

Northern Rhodesia 1961

IJ\ n)\Ò\A NORTHERN RHODESIA 1961 LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE SIX SHILLINGS NET COLONIAL OFFICE REPORT ON NORTHERN RHODESIA FOR THE YEAR I96I CONTENTS PART I Review of 1961 page 3 PART II Chapter 1 Population . .12 2 Occupations, Wages and Labour Organisations . 13 3 Public Finance and Taxation 19 4 Currency and Banking ...... 21 5 Commerce ........ 23 6 Production ........ 25 7 Social Services ....... 32 8 Legislation ........ 43 9 Justice, Police and Prisons ..... 44 10 Public Utilities and Public Works .... 50 11 Communications 61 12 Press, Broadcasting, Films and Government Informa¬ tion Services ....... 65 13 General ........ 71 14 Cultural and Social Activities ..... 82 PART III Chapter 1 Geography and Climate . .91 2 History ........ 96 3 Administration 101 4 Reading List 107 Appendices 121 A map will be found facing the last page PRINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, LUSAKA, NORTHERN RHODESIA 1962 PART I Review of 1961 Copper mining is the economic mainstay of the Territory and has, from the earliest days, been the principal support of the Northern Rhodesia economy. The economy measures taken by the Government in 1958, 1959 and 1960, in consequence of the reduced price of copper, were maintained in 1961. Expansion was very strictly controlled and was restricted to essential services. The average price of copper for the month of January, 1961, was £220 per ton. The average monthly price during the year varied between an upper limit of £242 per ton and a lower limit of £220 per ton and the year closed with a price for December of £230 per ton. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Federation to New Nationhood The Development of Nationalism in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1950-64 Power, Robert William Leonard Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Federation to New Nationhood The Development of Nationalism -

CHAPTER 16 January 1960 Brought a Visit to the Territory by the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan1, Fresh From

CHAPTER 16 January 1960 brought a visit to the Territory by the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan1, fresh from his "Winds of Change" speech to the South African Parliament. The African nationalist parties staged demonstrations for his benefit. MacMillan handled the demonstrators well at Livingstone Airport, walking a little towards them and waving as if, according to one report, "he was receiving an ovation from his constituents". The crowd loved it and there was much cheering and good humour. On 15 February 1960 the 26-member Advisory Commission on the future of the Federation, known after its chairman as the Monckton Commission, assembled at Victoria Falls. Lord Monckton of Brenchley2 had been an adviser to King Edward VIII at the time of the Abdication crisis and to the Nizam of Hyderabad when that prince was attempting to avoid his state's absorption into the Republic of India. Prospects for the future of the Federation were not good! The Northern Rhodesia Police escorted members of the Commission who toured the Territory taking evidence from all who cared to approach them. The Commissioner of Police gave evidence of intimidation and violence by the African nationalist movements, particularly by the United National Independence Party, of which Kenneth Kaunda had become president on his release from prison in January. Kaunda and his followers declared that the Monckton Commission was biased in favour of Sir Roy Welensky, the Federal Prime Minister. UNIP boycotted the Commission raising the slogan "Independence by October". They got it in October, but four years later. The Monckton Commission left Northern Rhodesia on 21 March and on the 27th Ian Macleod, the newly appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies, landed at Lusaka Airport3.