Post-Insurgency Rural Development Strategies in Mizoram: a Critical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Lunglei District

DISTRICT AGRICULTURE OFFICE LUNGLEI DISTRICT LUNGLEI 1. WEATHER CONDITION DISTRICT WISE RAINFALL ( IN MM) FOR THE YEAR 2010 NAME OF DISTRICT : LUNGLEI Sl.No Month 2010 ( in mm) Remarks 1 January - 2 February 0.10 3 March 81.66 4 April 80.90 5 May 271.50 6 June 509.85 7 July 443.50 8 August 552.25 9 September 516.70 10 October 375.50 11 November 0.50 12 December 67.33 Total 2899.79 2. CROP SITUATION FOR 3rd QUARTER KHARIF ASSESMENT Sl.No . Name of crops Year 2010-2011 Remarks Area(in Ha) Production(in MT) 1 CEREALS a) Paddy Jhum 4646 684716 b) Paddy WRC 472 761.5 Total : 5018 7609.1 2 MAIZE 1693 2871.5 3 TOPIOCA 38.5 519.1 4 PULSES a) Rice Bean 232 191.7 b) Arhar 19.2 21.3 c) Cowpea 222.9 455.3 d) F.Bean 10.8 13.9 Total : 485 682.2 5 OIL SEEDS a) Soyabean 238.5 228.1 b) Sesamum 296.8 143.5 c) Rape Mustard 50.3 31.5 Total : 585.6 403.1 6 COTTON 15 8.1 7 TOBACCO 54.2 41.1 8 SUGARCANE 77 242 9 POTATO 16.5 65 Total of Kharif 7982.8 14641.2 RABI PROSPECTS Sl.No. Name of crops Area covered Production Remarks in Ha expected(in MT) 1 PADDY a) Early 35 70 b) Late 31 62 Total : 66 132 2 MAIZE 64 148 3 PULSES a) Field Pea 41 47 b) Cowpea 192 532 4 OILSEEDS a) Mustard M-27 20 0.5 Total of Rabi 383 864 Grand Total of Kharif & Rabi 8365 15505.2 WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURE LAND DEVELOPMENT (WRC) HILL TERRACING PIGGERY POULTRY HORTICULTURE PLANTATION 3. -

5000 Ha Project Cost : 750.00 Lakhs Sesawm, Laisawral, Marpara

AREA : 5000 Ha Project Cost : 750.00 Lakhs Sesawm, Laisawral, Marpara ‘S’ Prepared by PIA Lunglei District, Mizoram 1 INDEX CHAPTER Page No. 1. Introduction ------------------------------------------- 3 2. Project Profile ------------------------------------------- 8 3. History of Project Villages & ------------------------------------------- 12 Basic Information 4. Participatory Rural Appraisal ------------------------------------------- 18 5. Problem Typology ------------------------------------------- 19 6. Project Intervention Plan ------------------------------------------- 22 7. DPR Plan Abstract ------------------------------------------- 23 8. Watershed Development Work (Phy. & Fin.) and Other Activities.------- 24 9. Preparatory Phase. ------------------------------------------- 26 10. Work Plan Details ------------------------------------------- 27 11. Consolidation and Withdrawal Phase. ----------------------------------- 54 12. Capacity Building Institute Identified ----------------------------------- 55 13. Institutional & Capacity building Plan ----------------------------------- 56 14. Basic Profile of the project location -------- ---------------------------58 15. Maps of the project ----------------------------------- 59 16. Institutional mechanism& Agreements. ----------------------------------- 63 17. SWOT Analysis of PIA. ----------------------------------- 64 18. PIA & Watershed Committee details. ----------------------------------- 65 19. Convergence Plans. ----------------------------------- 66 20. Expected Outcomes. -

Political Movements of the Hmars in Mizoram: a Historical Study

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Vol IV Issue 1, June 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 Political Movements of the Hmars in Mizoram: A Historical Study Vanlalliena Pulamte* Abstract This article studies political movement of the Hmar people and situation leading to the formation of Hmar National Union, Hmar Peoples’ Convention and Hmar Peoples’ Convention (Democratic). An analytical study of political problems of the Hmars in North Mizoram and various issues concerning Hmars’ political empowerment is undertaken. Keywords: Hmar, Mizo, Movement, People, Government Genesis of Hmar Movement Union, in Lushai Hills, the Hmars of The Hmar are scattered over Manipur, Manipur formed a voluntary association Mizoram, Cachar and North Cachar Hill known as ‘The Hmar Association’ by the districts of Assam. They are the original educated Hmars and elite groups to inhabitants of northern portion of preserve their customs, tradition, Mizoram and the present south-western language, culture, practice and identity. parts of Manipur. The Hmars themselves When the Mizo Union party was formed claim that historically and culturally they in the Lushai Hills, the Hmars Association were different from other tribes and they expected a lot of things from it and worked have a distinct language. Such claim is in collaboration with it (Pudaite Rosiem, more pronounced among the Hmars who 2002). live in the border areas or outside The main objective of the Mizo Union Mizoram (Lalsiamhnuna, 2011). The party was to preserve the socio-cultural Hmars are one of the Mizo groups and ethos of the Mizo people and maintain the they are attracted by the Mizo Union and Mizo identity. -

Gazette· Publish�D by Authority

P.egd. No. NE. 907 .... ' Mizoram· The - Gazette· Publish�d by Authority Vol. XVII' Aizaw1. Friday 10. 6. '198�. !ya'stha 20, SE 1910 Issue No. 24 Governmentaf'Mizoram , PA'RT I Appointments,.Postings. Transfers. Powers•. Leave and other Personal Notices and Orders. O!WERSBY GOVERNOR . N 0 T.l F I CAT I IJ N Mizoram No.A. 1901li50/86-PeFS (D), the. 8th JlUle,. 1988. The. Governor of is f pleased to grant extension of 76 (seventy SIX) days' earned leave with effect �om 9.5.1987 to 23.7.1987 and 8 (eight) days' Half Pay Leave with effect from 24.7.87 to 31.7.�7 to Pu J.M. Chowdhury, l.F.S., Conservator of Forests under the AIS (Leave) Rules, 1955 a, amended from time to time. r.ce During the·.,,'e of Pu I.M. Chowdhury, I.F.S. on leave, Pu C. Thang I.F.S. will lianal Deputy Conservator of Forests continue to look after works of Pu Ma Ch�wdhury, in addition to his own duties. �. 11 the interesLoC l' o.A.19013/2/80-APT(Aj, the 6th June,J988 ... .In public .eryice, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to order extension of the servic� of Pu J. 'Mal'Sawrna, MCS, Director. of AdminlstratiYe., Training Institute.�, I\!i.izoram for � period of 3 (thret) days with effect from 1.3.1988 (AN) while_he was pr0ceeding. CSR. on superannuation cpollsioll under Vol-II Article 459.. i �f' Consequen · UPOll-- the extension S�vi��"_Of Pu -1.,'M�l�w'ma, .\fCS,. -

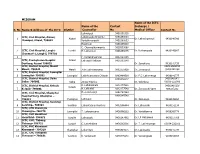

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

Telephone Directory

G EN ER AL E L EC TI ON T O L OC AL C O UN CI L S UN DE R M UN IC IP A L CO UN CI L & G EN ER AL E L EC TI ON T O V IL LA GE C OU N CI LS W IT HI N AIZAWL , L UNGLEI, S ER CHHIP , CHAM PHAI, K OLASIB, MAM IT DIST RICTS (NON-SI XTH SCHEDULE AREAS) 2 0 1 5 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY STATE ELECTION COMMISSION MIZORAM STATE ELECTION COMMISSION MIZORAM Website : www.sec.mizoram.gov.in Email : [email protected] Telefax : 0389 - 2300379 TABLE OF CONTENT SL. NO. NAME PAGE NO. 1. SEC OFFICERS & STAFF - 1 2. RAJ BHAVAN - 2 3. CHIEF MINISTER’S OFFICE - 2 4. CHIEF SECRETARY - 2 5.OBSERVERS - 2 6. LAD (Secretariat) - 3 Secretary, Addl. Secretary, Under Secretary, Superintendent. 7. LAD - Directorate - 3 8. GAD - Secretary, Addl. Secretary, - 3 Under Secretary 9. Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation - 3 9.DC/DEOs -4 10. EOs - 4 11. SDO(S)/SDO(C)/BDO - 4 - 6 12.POLICE -6 13. POLITICAL PARTIES - 6 14. ELECTRONIC MEDIA/ NEWS AGENCY - 6 STATE ELECTION COMMISSION, MIZORAM Officers & Staff Sl. Office/Fax/ Name Designation Address Mobile No. Res 2300378(O) 1 State Election Lower L. Tochhong 2300180(F) 9436142581 Commissioner Zarkawt 2321396 (R) P.A to G. Laldinthari Dawrpui West - 9862404704 Commissioner P.A to Ramhlun C. Lalrinkimi - 9862948329 Commissioner Venglai 2 H. Darzika, MCS 2300380(O) Secretary Durtlang 9436154514 (Retd.) 2300180(F) P.A to C. Lalremruati Khatla - 9862373009 Secretary H.D Lalpekmawia, Under 3 Chhinga Veng 2300475(O) 8974189546 MCS Secretary 4 Vanlalmuana Superintendent Laipuitlang 2300401(O) 9436195736 5 Zolianzuali Assistant Tuikhuahtlang - 9436354347 6 Judy M.S Dawngliani U.D.C Tuikual South - 9862587769 H.S Lenny Mission 7 D.E Operator - 9862017124 Vanlalmuana Vengthlang Bungkawn 9862312936/ 8 R. -

MIZORAM Email: [email protected]

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN EDUCATION AIZAWL : : MIZORAM www.iasemz.edu.in email: [email protected]. No. 8794002542 Fax: 0389-2310565 PB.No.46 No.J.14011/2/2021-EDC(IASE) Dated 19th July, 2021 LIST OF CANDIDATES ELIGIBLE FOR PERSONAL INTERVIEW (B.ED.) FOR THE ACADEMIC SESSION 2021-2023 Sl. Registered NAME Father’s/Mother’s/Guardian’s Address No. Sl. No. Name 1 2 ABRAHAM C.Thanhranga Electric Veng,Lawngtlai VANLALMALSAWMTLUANGA CHINZAH 2 3 AKASH KUSUM CHAKMA Basak Chandra Chakma Kamalanagar, Chawngte 3 4 ALBERT LALLAWMSANGA R.Lalmuanchhana Kawnveng,Darlawn 4 5 ALICE MALSAWMTHANGI H.Lalngaizuala Chaltlang Lily Veng 5 8 AMAR JYOTI CHAKMA Basak Chandra Chakma Kamalanagar Iv, Chawngte 6 9 AMITA RANI ROY Kartik Roy Raj Bhawan,Aizawl 7 11 ANDREW F LALRINSANGA F.Lalhmingliana Upper Kanan 8 17 ANNETTE MALSAWMZUALI Lalsanglura Phq, Khatla, Aizawl 9 18 ANTHONY SAIDINGPUIA Stephen Lalzirliana Anthony Saidingpuia 10 21 R. VANLALHMUNMAWII R. Lalsawma Hnahthial Bazar Veng 11 28 BABY LALBIAKSANGI T.Lalnunmawia Salem Veng 12 30 BABY LALRUATSANGI R.Laltanpuia Kawnpui 13 31 BARBARA LALRUATDIKI T.Vanlalpara Darlawn 14 34 BEIHNIARILI SYUHLO Bl Syuhlo College Vaih-I, Siaha 15 36 BENJAMIN LALRINAWMA K. Vanlalmuanpuia N. E. Khawdungsei 16 46 BRENDA TLAU Lalchungnunga Ramhlun Vengthlang Aizawl 17 47 BRIGIT RAMENGMAWII Joseph Dawngliana 4/63 A Kulikawn, Aizawl 18 50 C. LALMALSAWMA C. Zohmingthanga Durtlang Mualveng, Aizawl 19 51 C. LALREMRUATA Lalzemawia Dinthar Veng, Serchhip 20 57 C.LALAWMPUII C.Lalnidenga Bungkawn Dam Veng 21 59 C. LALCHHANCHHUAHI C. Rammawia Zohmun 22 61 C LALCHHUANMAWII C Lalhmachhuana H-48zemabawk Zokhawsang Veng 23 62 C. -

Traditional Anti-Malarial Drugs from Serchhip and Lunglei Districts of Mizoram

Current Trends in Pharmaceutical Research Vol. 6, Issue 1, 2019 ISSN: 2319-4820 © Dibrugarh University www.dibru.ac.in/ctpr Research article TRADITIONAL ANTI-MALARIAL DRUGS FROM SERCHHIP AND LUNGLEI DISTRICTS OF MIZORAM Laldinsanga, Himangshu Sarma, Taslima Jahan, Ashis Kumar Goswami, Hemanta Kumar Sharma* Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh- 786004, Assam, India Abstract Background: Traditional or folk or indigenous medicine concerns the health practices, knowledge and faith of different indigenous communities. It is the application of a single or combination of parts of plants, animals and mineral-based medications to diagnose, cure, mitigate or prevent illnesses or diseases. The traditional medicine has a wide application even today, especially in developing countries, where modern health services are limited. Objective: The objective of this survey was to identify the medicinal plants used by different tribal communities as a folk remedy to cure malaria and fever in rural Mizoram, a state of North-East India. Methods: An ethnobotanical survey was carried in between January 2012 to April 2012 by interviewing traditional healers of Mizoram. The survey was carried out in the south and central part of Serchhip and Lunglei Districts of Mizoram. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Laldinsanga et al. Results and Discussion: Based on the exhaustive interviews with the local healers practicing indigenous system of medicine a detailed list of plants were prepared. The list was prepared taking into consideration the information obtained from books related to traditional medicinal plants. The list consists of 52 plant species from 36 families, which claim ethnomedical indication to treat malaria and fever. -

SIAHA DISTRICT PROFILE History: Siaha District Is One of the Eight

SIAHA DISTRICT PROFILE History: Siaha District is one of the eight districts of Mizoram state in India. The district is bounded on the north and northwest by Lunglei district, on the west by Lawngtlai District and on the south and east by Myanmar. The district occupies an area of 1399.9 km². Siaha town is the administrative headquarters of the district. The population had decreased from 60,823 (in 2001 census) to 56,574 (in 2011 census). It is the least populous district of Mizoram (out of 8) Siaha District was formerly part of Chhimtuipui District. In 1998 when Chhimtuipui District was split in half, the half that became Siaha District was briefly called by the old name Chhimtuipui District. Siaha (official name given by the Mara Autonomous District Council, popularly known as Saiha) is a census town in Siaha district in the Indian north- eastern state of Mizoram. It is the Headquarters of the Mara Autonomous District Council, one of the three autonomous district councils within Mizoram. It is located in the South Central part of the state. The word 'Siaha' in the local Mara language comes from 'Sia' for Masia which means elephant and 'ha' meaning tooth - An elephant tooth. It was a place where a large amount of elephant teeth were found. Though the local people name the town as Siaha, Mizos called it by the name 'Saiha', which is purely a translated term in Mizo language. Siaha is a commercial hub for Mara people. Area : The district occupies an area of 1399.9 km² Population : 56,366 (as per 2011 census) Literacy rate : 90.01% , Male - 21,685, Female - 20,232 (as per 2011 census) Number of Blocks : There are two (2) Blocks (Siaha RD and Tipa RD) Divisions : There are two (2) Divisions (Siaha and Tipa) Villages : There are 92 Villages in the District Police Station : There are three (3) Police Stations within the District. -

CEA Aizawl & Serchhip-Graduate & Tech

NO.B.13011/11/2019-WB (LESDE) GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM MIZORAM BUILDING & OTHER CONSTRUCTION WORKERS’ WELFARE BOARD Dated Aizawl, the 11 th December 2019 SANCTION ORDER Sanction is hereby accorded to an amount of Rs.5,28,000 /- (Rupees Five Lakh Twenty Eight Thousand only) from Mizoram Building & Other Construction Workers’ Welfare Scheme in favour of Children Educational Assistance 2019-2020 of Graduate/Technical Course for 132 students from Aizawl & Serchhip District as listed below: SL.NO HMING NU/PA HMING VENG/KHUA REG.NO AMNT ACCOUNT.NO IFSC 1 LALHMINGMAWIA DENGHMINGLIANI ARMED VENG 5209/2018(A) 4000 901820010451 SBINORRMIGB 2 LALLIANSANGPUII LIANZELI BAKTAWNG VENGLAI 5268(A)2019 4000 25020017787 SBINORRMIGB 3 LALTHIANGHLIMI PC VANLALFAKA BETHLEHEM MB&OCWWB(A)2018 4000 110182001329 YESBOMAB002 4 C ZONUNSANGI C LALMAWIZUALA BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 14461(A)2019 4000 25053054710 SBINORRMIGB 5 LALRUATPUIA LALMUANPUII BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 14512(A)2019 4000 25002049722 SBINORRMIGB 6 H LALCHHANHIMI H LALNUNMAWII BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 1588/RN(A)2019 4000 97003447831 SBINORRMIGB 7 LALHUNMAWII A LALREMSIAMA BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 1806/RN(A)2019 4000 97000703218 SBINORRMIGB 8 LALTLANKIMA A LALREMSIAMA BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 1806/RN(A)2019 4000 97000703218 SBINORRMIGB 9 VANLALCHHANDAMA B LALRAMZAUVA BETHLEHEM VENGTHLANG 3163/RN(A)2018 4000 97003851437 SBINORRMIGB 10 NANCY VANHLUPUII LALRINAWMI BUANGPUI 4244(S)2019 4000 25028040152 SBINORRMIGB 11 LALHMINGSANGI LALSIAMLIANI CHALTLANG 14705(A)2019 4000 97009376780 SBINORRMIGB 12 RODINGPUII R ZOSIAMLIANA CHANMARI -

Town Survey Report Lunglei, Part XB, Series-31, Mizoram

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 PART-XB SERIES 31 MIZORAM TOWN SURVEY REPORT LUNGLEI B.SATYANARAYANA Deputy Director Directorate of Census Operations MIZORAM ~J.a. LIST OF MAps AND PHOTOGRAPHS (ii) FOREWORD (iii) .. PREFACE . (v)-(vi) NOTIONAL MAP OF LUNGLBI TOWN (vii) CHAPTER I Introduction • 1-8 IlHAPlER II History and Growth of the TOWB 9-11 CHAPTER III Amenities and Services-History of Growth and the Present Positi"n • 12-1k CHAPTER IV Economic Life of the Town 19-34. CHAPTER V Ethnic and Selected Socio-Demograpkic C.laara~tori8tici oftke PopulatioR 35-42 CHAPTER VI Migration and Settlement of Families • 43-51 CHAPTER VII Neighbourhood Pattern • 54-56 CHAPTER vm Family Life in the Tows • • • CHAPTER IX Housing and Material Culture • • 63-72 CHAPTER X Slums, Blighted and other Areas with Sub-standard Living Conditions. 73 CHAPTER XI Organisation of Power and Prestige • • 74-82 CHAPTER XII Leisure and Recreation, Social ParticipatioJl, Social Awareness, Religion and Crime • 83-93 OHAPTER XIII Linkages and ContiJl1la • • • • 94-98 CONOLUSION • • • • 99-100 6LOSSARY • 101 LIST OF MAPS'·~ PMOrOGRAPHS Facing Page . , , Notional Map of Lunglei town (vii) Baptist Church Serkawn 4 Stteet (one of the business streets of Lunglei Town) ". '. 5 B.s Station (MST) 6 Memorial Stone erected for the memory of the first Baptist Church founded in Mizoram 7, T~ First Ba.ptist Church BuHdingin Mjz()ralp .. .. " ... " 8 Stone Bridge over Sipai Lui ~O Circuit House 11 Post Office ' 1~ Government High School " 16 Government College 16 Serkawn Christian High School 17'1 Civil Hospital 18 Christian Hospital Serkawn 19<' R;'f.P. -

A Study of Correlation Between the Mnf And

© 2018 JETIR August 2018, Volume 5, Issue 8 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) TRACING THE FLINCH OF INSURGENCY (A STUDY OF CORRELATION BETWEEN THE MNF AND ‘MAUTAM’ FAMINE IN MIZORAM) Dr Sakhawliana Assistant Professor, Department of Public Administration Government Kamalanagar College, Mizoram ABSTRACT Insurgency is causes, basically by political unwillingness of the administration. It is the call of the nations that the political track of different party’s should ensure nation building, and fixing the socio-economic menace of the general public. The prototyped imperialist, of premeditated coercive security and control of administration might not be viable to all sorts of establishments. Experience on the vital effects of the morale and psychology of the people can be seen in Mizoram, one of the North eastern states of India. This state has been under the profanity of insurgency for barely 20 years (1996-1986). It was said that after the famine cause by bamboo flowering, the philanthropic organisation of Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF) rechristened to form new political party of the Mizo National Front (MNF) and thrive for independence movement from the Indian Union. The hostility was brought by Mizo National Front (MNF) alias Mizo National Army (MNA), as its underground army wing, from one side and the Indian Army on the other. Over the year, the Indian Army and the MNA fought in tactical guerrilla warfare by using most sophisticated weapons of the 21st century. Therefore, it is impetus to unveil the insight of insurgency, in general, and the birth of the MNF for secession movement, in particular.