Economic Co-Operation and Elite Complementarity in the Nest Indies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

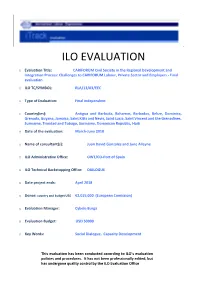

Challenges to CARIFORUM Labour, Private Sector and Employers - Final Evaluation

ILO EVALUATION o Evaluation Title: CARIFORUM Civil Society in the Regional Development and Integration Process: Challenges to CARIFORUM Labour, Private Sector and Employers - Final evaluation o ILO TC/SYMBOL: RLA/13/03/EEC o Type of Evaluation: Final independent o Country(ies): Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Dominican Republic, Haiti o Date of the evaluation: March-June 2018 o Name of consultant(s): Juan David Gonzales and June Alleyne o ILO Administrative Office: DWT/CO-Port of Spain o ILO Technical Backstopping Office: DIALOGUE o Date project ends: April 2018 o Donor: country and budget US$ €2,015,000 (European Comission) o Evaluation Manager: Cybele Burga o Evaluation Budget: USD 50000 o Key Words: Social Dialogue, Capacity Development This evaluation has been conducted according to ILO’s evaluation policies and procedures. It has not been professionally edited, but has undergone quality control by the ILO Evaluation Office FINAL EVALUATION REPORT I Executive Summary Background and context In October 2008, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Dominican Republic, being members of the Forum of the Caribbean Group of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (CARIFORUM), signed the CARIFORUM-EU Economic Partnership Agreement -

February 2010 with Updates SJ.P65

February 2010 (Revised Edition) Decent work a priority for Belize Government launches region’s second Decent Work Country Programme The Government of Belize officially October, 2009. The launch follows Trade Union Congress and other launched the region’s second Decent Cabinet’s approval of the Programme on stakeholders, at a national workshop Work Country Programme on 29 14 July 2009. By concluding a Decent convened on 26-28 January 2009, in Work Country Programme (DWCP), the collaboration with the ILO. The Belize Government commits to working with the DWCP will focus on the following three social partners and priority areas: other stakeholders to (i) modernization and promote the Decent harmonization of Work Agenda in their national labour national development legislation in line with strategies. international labour The International Labour The Decent Work standards and Organization (ILO) is the United Agenda focuses on CARICOM Model Nations agency devoted to ways in which creating Labour Laws; advancing opportunities for women jobs, while promoting (ii) improvement of and men to obtain decent and respect for rights, skills and employability productive work in conditions of social protection, and (particularly for women freedom, equity, security and consensus-building and youth) and the human dignity. through social development of a Its main aims are to promote rights dialogue, can be made supportive labour at work, encourage decent central to social and market information employment opportunities, enhance economic system; and social protection and strengthen development. (iii)institutional dialogue in handling work-related issues. The DWCP was strengthening of the developed by the The Hon. Gabriel A. Martinez, social partners. -

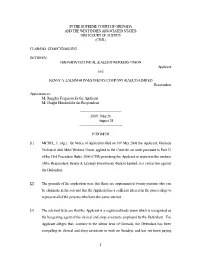

Grenada Technical and Allied Workers Union V Kenny Lalsingh Investments

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GRENADA AND THE WEST INDIES ASSOCIATED STATES HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE (CIVIL) CLAIM NO. GDAHCV2008/0292 BETWEEN: GRENADA TECHNICAL & ALLIED WORKERS UNION Applicant and KENNY A. LALSINGH INVESTMENTS COMPANY (KALICO) LIMITED Respondent Appearances: Mr. Ruggles Ferguson for the Applicant Mr. Dwight Horsford for the Respondent --------------------------------------- 2009: May 26 August 28 ---------------------------------------- JUDGMENT [1] MICHEL, J. (Ag.): By Notice of Application filed on 16th May 2008 the Applicant, Grenada Technical And Allied Workers Union, applied to the Court for an order pursuant to Part 21 of the Civil Procedure Rules 2000 (CPR) permitting the Applicant to represent the workers of the Respondent, Kenny A. Lalsingh Investments (Kalico) Limited, in a civil action against the Defendant. [2] The grounds of the application were that there are approximately twenty persons who can be claimants in the suit and that the Applicant has a sufficient interest in the proceedings to represent all of the persons who have the same interest. [3] The relevant facts are that the Applicant is a registered trade union which is recognised as the bargaining agent of the clerical and shop assistants employed by the Defendant. The Applicant alleges that, contrary to the labour laws of Grenada, the Defendant has been compelling its clerical and shop assistants to work on Sundays and has not been paying 1 them overtime for so doing. The Applicant therefore seeks the Court’s permission to institute proceedings against the Defendant on behalf of the affected employees to right the alleged wrong. [4] The matter first came before the Judge in Chambers on 31st October 2008 and was adjourned to 28th November 2008. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, M Ichigan

71^8621 MURRAY, Winston Churchill, 19 34- LABOR, POLITICS AMD SOCIAL LEGISLATION IN THE BRITISH WEST INDIES 1834-1970. The American University, Ph.D., 1970 History, modern University Microfilms,A XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan 0 1971 WINSTON CHURCHILL MURRAY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LABOR, POLITICS AND SOCIAL LEGISLATION TI1E BRITISH WEST INDIES 1034-1970 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School The American University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Winston C. Hurray June 1970 a h s t h a c t Statement of the Problem. It is the purpose o£ this study (1) to ascertain how social legislation has affected the evolution of political trade unionism in the West Indies; (2) to determine how social legisla tion In the 1930's and after independence In 19G2 by native politicians contributed to the political style and culture orientation of labor vis-a-vis the employer. The author has made two assumptions: (1) the assumption on wages; and (2) the assumption on taxation. This study assumes that wage policy and wage movements in colonial society were influenced by the level of economic activity in an agricultural society and that wages of the worker were not far removed from the subsistence level. Therefore, such wages wore employed as a form of social control by the dominant planting aris tocracy over a weak but numerically stronger laboring class. It is asaumcd that taxes (direct and indirect) were not instituted to foster economic growth and national development. This historical research leads to four basic conclusionsi (1) that prior to 1937, social legislation imposed on the weaker segment of the society denied the laboring blacks the fundamental rights of suffrage and collective bargaining, (2) that the denial of the right to participate in the society coupled with the social plight of the worker contributed to the politicization of West Indian labor after 1937; (3) that West Indian laboringmen are the. -

Maurice Bishop’S Speeches, 1979-I983 : a Memorial Volume

(l()NIIMl'()lH\lJV Hl‘»l()HY NOBODY S BACKYARD Muurico Bishop's Spee<:lu~r. 1‘)/‘) 1983 A l\/lOfT\Ofl(1l Volume l\/1/\lll\’l( ll lllf>ll( )l’ llt Nnhmly'ri Htltiltyilltl l'- .1 lllI"lt|t>ll.ll \tlllllllI‘ ill '.|><‘1-1 ll-~n In, ll!" l.ll" lllllllt‘ l\/lnnult-i (ll l|ll‘lI.ltl.l -llltl l1‘.I<lt‘l 1-l lln-1.1--ii.nl.i ll1"\iillllll1ll l\/l.ll|I|t 1' lll'.lni|i l'l|ll|ln] |i.|tl|t lll.|l '.lt|-'.x Itll lllI' '.|n'I‘I llI"- til ll|~' l.l‘.I l\/Vllflllllill yt'.||'.til lll‘,llll', llll‘»l1llll|lll'll4‘l|'.l\4‘ I lllll'l lltlll |‘r.| llllllllt‘ l()ll1l‘ltllll1..lllll‘»|llltll|till-lllll-|ll.ll\“.l'. lllV\lll(ll lllt>lllt‘l lll‘-ll l'1|\,/‘I l‘Xl)ll"v‘»|()ll l\/ltlllllllt,‘ lliulniii ~. ‘-lllllllll .int 1- 11111". l.n lH'\llllll 1 ilI‘ll.|tl.l -lllll lll‘- ltlt'.|‘. lll lll1?(,t)lll1).lll\/(ll other lll|ltlV\/tlllll lll.lll‘,'l'.l|l~1‘/\lli*l|rlI{ t .ilii.il {l1l(ll\/l()l1<llt|l1t' V\/Ill ll\/1' (lll lriiit; .|l1t-| hi-. lll‘.llll llllll l‘|lll‘ll t|l\/\/<l\'- l()(’(/l/(‘t){(', lie§.|>t~.'|l\:. not llllll In (il1‘ll.|tll.lll‘-tllltl \N~--.I |iirli.ni-., lllll tn all black <'lll(lW()ll<lll1] l)t'(l[llt‘-llltl lln'rititiii~-.'.t-il (ll lln' lhinl Wllllll By turns illlillylltiill, moving], .'iinii:;int;, his lllllll\lllt_] i.in<_;t". -

Slavery and the British Country House

Slavery and the British Country House Edited by Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann Slavery and the � British Country House � Edited by Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann Published by English Heritage, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH www.english-heritage.org.uk English Heritage is the Government’s lead body for the historic environment. © Individual authors 2013 The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and not necessarily those of English Heritage. Figures 2.2, 2.5, 2.6, 3.2, 3.16 and 12.9 are all based on Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100024900. First published 2013 ISBN 978 1 84802 064 1 Product code 51552 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. � The right of the authors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. � All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Application for the reproduction of images should be made to English Heritage. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and we apologise in advance for any unintentional omissions, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition of this book. For more information about images from the English Heritage Archive, contact Archives Services Team, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH; telephone (01793) 414600. -

Company List

COMPANY_CODE COMPANY_NAME ADDRESS 256455 ATTACH A LEG GRENADA MT.MORITZST.GEORGE ID623249GD TESSIL MODESTE-LEWIS GOUYAVEST. JOHN 0000001494 GRENADA CAR RENTALS [C.D.F ENTERPRISES LIMITED]GRAND ANSEST.GEORGE 0000001914 GRENLAS MANAGEMENT GRENADA POINT SALINESP.O. BOX386 0000001955 S & N SUPERMARKET SETON BROWN STREETGREMVILLEST. ANDREWS 00000040000001 DONAVON,CONSTANCE CROSS STREETST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 0000004494 GRENADA CAR RENTALS [C.D.F ENTERPRISES LIMITED]GRAND ANSEST.GEORGE 00000050000002 COBB-SIMON,JOAN A ST. PAUL'SST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000060000101 AUGUSTINE,BENEDICT MARIANST. GEORGE 00000070000007 ANTOINE,TREVOR MT. GAYST. GEORGE 00000090000008 ALEXIS,MARY HARVEY VALECARRIACOU 00000130000011 ALFRED,MAUDLYN MELVILLE STREETST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000140000013 ALEXANDER,RENWICK ST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000150000090 CORION,GARVEY O L'ESTERREST. ANDREW 00000180000015 ANDALL,PETER RIVER ROADST. GEORGE 00000180001951 ANDALL,PETER ST. PAULSST. GEORGE 00000180001952 ANDALL,PETER RIVER ROADST. GEORGE 00000180001953 ANDALL,PETER ST. JOHNSST. ANDREW 00000180001954 ANDALL,PETER GRENVILLEST. ANDREW 00000180002419 ANDALL,PETER SPRINGSST. GEORGE 00000200000019 ADAMS,SHEREE-ANN LANCE AUX EPINESST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000220000094 CONNAUGHT,SHEILA J VICTORIA STREETVICTORIAST. MARK 00000230000005 DUNCAN,MARY LAGOON ROADST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000240000006 ARNOLD,NORBERT ARCHIBALD AVENUEST. GEORGE 00000250000010 DRAGON,FABIAN E. GRENVILLE STREETST. GEORGE'SST. GEORGE 00000260000012 CLYNE,MICHAEL O WESTERHALLWESTERHALLST. DAVID 00000270000014 -

Training Conducted the ILO Subregional Office for the Caribbean February 2005 – May 2010 Table of Contents

Training conducted the ILO Subregional Office for the Caribbean February 2005 – May 2010 Table of contents 2005 HIV/AIDS focal point training workshop HIV/AIDS focal point training workshop HIV/AIDS focal point training workshop Government focal point training (HIV/AIDS) Behaviour change communication strategy development workshop (HIV/AIDS) ILO subregional workshop for Caribbean employers’ organizations on small and medium enterprises in the informal sector Behaviour change communication strategy development workshop (HIV/AIDS) Focal point training workshop (HIV/AIDS) Occupational Safety and Health Inspection Systems Behaviour change communication strategy development workshop (HIV/AIDS) HIV/AIDS focal point training – trade unions Behaviour change communication strategy development workshop (HIV/AIDS) Caribbean subregional training workshop on labour and occupational health inspectors/officers in agriculture Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Trade union seminar on information technology and the creation of world wide Websites 2006 Peer education training (HIV/AIDS) Peer refresher training (HIV/AIDS) Peer refresher training (HIV/AIDS) Behaviour change communication (HIV/AIDS) Peer refresher training (HIV/AIDS) Workers’ organization and member-representatives workplace policy development (HIV/AIDS) Peer Refresher Training (HIV/AIDS) Training of trainers workshop -

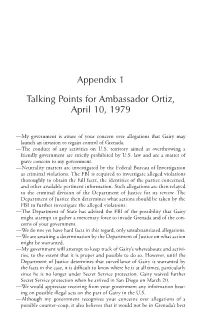

Appendix 1 Talking Points for Ambassador Ortiz, April 10, 1979

Appendix 1 Talking Points for Ambassador Ortiz, April 10, 1979 —My government is aware of your concern over allegations that Gairy may launch an invasion to regain control of Grenada. —The conduct of any activities on U.S. territory aimed at overthrowing a friendly government are strictly prohibited by U.S. law and are a matter of grave concern to my government. —Neutrality matters are investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as criminal violations. The FBI is required to investigate alleged violations thoroughly to obtain the full facts, the identities of the parties concerned, and other available pertinent information. Such allegations are then relayed to the criminal division of the Department of Justice for its review. The Department of Justice then determines what actions should be taken by the FBI to further investigate the alleged violations. —The Department of State has advised the FBI of the possibility that Gairy might attempt to gather a mercenary force to invade Grenada and of the con- cerns of your government. —We do not yet have hard facts in this regard, only unsubstantiated allegations. —We are awaiting a determination by the Department of Justice on what action might be warranted. —My government will attempt to keep track of Gairy’s whereabouts and activi- ties, to the extent that it is proper and possible to do so. However, until the Department of Justice determines that surveillance of Gairy is warranted by the facts in the case, it is difficult to know where he is at all times, particularly since he is no longer under Secret Service protection. -

Government of Grenada Gender Equality Policy and Action

2014 - 2024 MINISTRY OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING GOVERNMENT OF GRENADA GOVERNMENT OF GRENADA GENDER EQUALITY POLICY AND ACTION PLAN (GEPAP) 2014 - 2024 APPROVED BY THE CABINET OF GRENADA JUNE 10, 2014 FOR IMPLEMENTATION BY GOVERNMENT MINISTRIES AND DEPARTMENTS LEAD AGENCY DIVISION OF GENDER AND FAMILY AFFAIRS MINISTRY OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING DEVELOPED WITH SUPPORT FROM UNITED NATIONS ENTITY FOR GENDER EQUALITY AND THE EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN (UN WOMEN) AND PARTNERSHIP FOR THE GRENADA COUNTRY GENDER ASSESSMENT WITH CARIBBEAN DEVELOPMENT BANK (CDB) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The preparation of this national Gender Equality Policy and Action Plan (GEPAP) 2014–2024 has been led by the Division of Gender and Family Affairs, Ministry of Social Development and Housing (MoSDH), Government of Grenada. Thanks are expressed to the many organisations and individuals in government, civil society and the private sector who have contributed to the development of the GEPAP. Hon. Delma Thomas, Minister of Social Development and Housing (MoSDH); Mrs. Elizabeth Henry- Greenidge, Permanent Secretary and Ms. Barbara Charles, Acting Permanent Secretary, MoSDH; and Mr. Timothy Antoine, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance and Energy, Economic Development, Trade, Planning and Cooperatives played leadership roles in the process. Ms. Elaine Henry-McQueen, Senior Programme Officer, Division of Gender and Family Affairs (DGFA), MoSDH performed leadership and technical functions in developing GEPAP. Staff members of the DGFA played a critical role in the process of developing GEPAP, among whom Ms. Jicinta Alexis who was the local counterpart to the Consultant, Ms. Alice Victor, Mr. Maurice Cox and Mr Kwesi Davidson deserve special mention. Government senior officials and technical staff, both individually and collectively, contributed statistical data and critical feedback at various stages of the process. -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications the GRENADIAN REVOLUTION, 1979-1983; the POLITICAL ECONOMY of Ftn ATTEMPT at REVOLUTIONARY TRANSFORMATION in a CARIBBEAN

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/108795/ Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE GRENADIAN REVOLUTION, 1979-1983; THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ftN ATTEMPT AT REVOLUTIONARY TRANSFORMATION IN A CARIBBEAN MINI-STATE. Fitzroy Ambursley, B.A. of the req uir e m e n t s of the u e r s i t y of W a r w i c k , Uiest Midlands Department of Sociology. January 1985. University of Warwick Library, Coventry AUTHOR DEGREE DATE OF DEPOSIT TITLE I agree that this thesis shall be available in accordance with the regulations governing the University of Warwick theses. I agree that the summary of this thesis may be submitted for publication. Any proposal to restrict access to the thesis and/or publication of the summary (normally only up to three years from the date of the deposit) must be made by the candidate in writing to the Postgraduate Section, Academic Office at the earliest opportunity. See paragraphs 9 and 11 of "Requirements for the Presentation of Research Theses". I agree that the thesis may be photocopied (single copies for study purposes only) YES/NO (The maximum period of restricted access to be granted should not normally exceed three years, although further extensions of up to a maximum of five years will be considered.) Author's Signature User's Declaration (i) I undertake not to quote or make use of any information from this thesis without making acknowledgment to the author.