In Defense of Intelligent Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospects for Theistic Science

Dialogue: Article Prospects for Theistic Science Prospects for Theistic Science Roy Clouser This article first tackles the issue of defining what counts as a religious belief, and shows why obtaining such a definition opens the way to discovering a deeper level of interaction between divinity beliefs and the scientific enterprise than the prevailing views of the science/religion relation allow for. This deeper level of interaction is illustrated by applying it to twentieth- century atomic physics. It is then shown why this level of interaction implies a distinctive anti-reductionist perspective from which theists should do science, a perspective in which belief in God acts as a regulative presupposition. Finally, reduction as a strategy for explanation is critiqued and found bankrupt. Roy Clouser mong theists, the most popular view positive content for virtually every science. I [think that] A of the engagement between science And some theists have proposed still other and religion (henceforth the S/R rela- ideas of thicker engagement. For example, religious belief tion) is a minimalist one. They see the role of recent writers have claimed that theism’s religious belief to science as primarily nega- positive contribution to science is not so much engages science tive such that any theory can be acceptable that of providing actual content to theories to a theist so long as it does not outright con- as it is that religious ideas inspire scientific in a way that tradict any revealed truth of Faith. On this ideas. There are permutations on these views, view, conflict between science and religion of course, and a number of mix-and-match is not merely is not only possible but is the only (or the combinations of them are possible. -

Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals

UNDERSTANDING THE INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONIST MOVEMENT: ITS TRUE NATURE AND GOALS A POSITION PAPER FROM THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY OFFICE OF PUBLIC POLICY AUTHOR: BARBARA FORREST, Ph.D. Reviewing Committee: Paul Kurtz, Ph.D.; Austin Dacey, Ph.D.; Stuart D. Jordan, Ph.D.; Ronald A. Lindsay, J. D., Ph.D.; John Shook, Ph.D.; Toni Van Pelt DATED: MAY 2007 ( AMENDED JULY 2007) Copyright © 2007 Center for Inquiry, Inc. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the Center for Inquiry, Inc. Table of Contents Section I. Introduction: What is at stake in the dispute over intelligent design?.................. 1 Section II. What is the intelligent design creationist movement? ........................................ 2 Section III. The historical and legal background of intelligent design creationism ................ 6 Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) ............................................................................ 6 McLean v. Arkansas (1982) .............................................................................. 6 Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) ............................................................................. 7 Section IV. The ID movement’s aims and strategy .............................................................. 9 The “Wedge Strategy” ..................................................................................... -

Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R

Author Exchange Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R. Venema A Reply to Meyer Dennis R. Venema Weizsäcker’s book The World View of Physics is still keeping me very busy. It has again brought home to me quite clearly how wrong it is to use God as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat. We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know; God wants us to realize his presence, not in unsolved problems but in those that are solved. Dietrich Bonhoeffer1 am thankful for this opportunity to nature, is the result of intelligence. More- reply to Stephen Meyer’s criticisms over, this assertion is proffered as the I 2 of my review of his book Signature logical basis for inferring design for the in the Cell (hereafter Signature). Meyer’s origin of biological information: if infor- critiques of my review fall into two gen- mation only ever arises from intelli- eral categories. First, he claims I mistook gence, then the mere presence of Signature for an argument against bio- information demonstrates design. A few logical evolution, rendering several of examples from Signature make the point my arguments superfluous. Secondly, easily: Meyer asserts that I have failed to refute … historical scientists can show that his thesis by not providing a “causally a presently acting cause must have adequate alternative explanation” for the been present in the past because the origin of life in that the few relevant cri- proposed candidate is the only known tiques I do provide are “deeply flawed.” cause of the effect in question. -

Comments on Clouser's Claims for Theistic Science

Dialogue: Response Comments on Clouser’s Claims for Theistic Science Comments on Clouser’s Claims for Theistic Science Hans Halvorson n “Prospects for Theistic Science,” Roy First, Clouser claims that theists and I Clouser sketches a framework for the atheists alike believe that there is a privi- relationship between religious and sci- leged class of self-existent (or “divine”) entific beliefs. In particular, he develops— beings; they differ only on which beings building on previous work1—a neo-Calvin- they identify as divine. Clouser also claims ist view, according to which religious belief that religious beliefs regulate scientific theo- is a presupposition of, and is relevant to, rizing because a scientist will attempt to Hans Halvorson any other body of beliefs. reduce everything to (or, explain everything in terms of) what she takes to be the self- According to Clouser, we should expect existent beings. But this proposal comes into religious beliefs to play a “regulative,” rather tension with Clouser’s claim that the theist than a “constitutive” role with regard to sci- should be a nonreductionist. In particular, entific theorizing. (Indeed, Clouser indicates if Clouser is correct that a scientist will try Clouser’s that religious beliefs do, in fact, regulate to explain everything in terms of what she scientific theorizing—whether or not we are thinks are the self-existent beings, then will proposal aware of it.) That is, while we should not not the theistic scientist attempt to explain typically expect religious beliefs to provide everything in terms of his divinity, viz., the content of scientific theories, we should holds out God? If this is so, then in what sense is the expect religious beliefs to provide a method- theist different from the atheist? In what ological framework within which scientific the promise sense is the theist a nonreductionist? theories are developed and evaluated. -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

Arguments from Design

Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Victoria S. Harrison University of Glasgow This is an archived version of ‘Arguments form Design: A Self-defeating Strategy?’, published in Philosophia 33 (2005): 297–317. Dr V. Harrison Department of Philosophy 69 Oakfield Avenue University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8LT Scotland UK E-mail: [email protected] Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Abstract: In this article, after reviewing traditional arguments from design, I consider some more recent versions: the so-called ‘new design arguments’ for the existence of God. These arguments enjoy an apparent advantage over the traditional arguments from design by avoiding some of Hume’s famous criticisms. However, in seeking to render religion and science compatible, it seems that they require a modification not only of our scientific understanding but also of the traditional conception of God. Moreover, there is a key problem with arguments from design that Mill raised to which the new arguments seem no less vulnerable than the older versions. The view that science and religion are complementary has at least one significant advantage over other positions, such as the view that they are in an antagonistic relationship or the view that they are so incommensurable that they are neither complementary nor antagonistic. The advantage is that it aspires to provide a unified worldview that is sensitive to the claims of both science and religion. And surely, such a worldview, if available, would seem to be superior to one in which, say, scientific and religious claims were held despite their obvious contradictions. -

Discussion on Application for Interior Space Design and the Application of Interior Design Style

3rd International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2016) Discussion on Application for Interior Space Design and the Application of Interior Design Style Xiaodong Zhang Institute of Environmental art design, Hebei Institute of Fine Art, Shijiazhuang hebei, 050700, China Keywords: interior design, psychological space, design style Abstract. Interior design is the essence of the interior space design, including physical space design and psychological space design two levels. Interior design style is an important issue for interior designers and owners. Through analysis and Research on the relationships between design and interior design style of interior space, summed up the "interior space design to create a style of interior design" and "interior design style shape the psychological space two obvious characteristics. Interior Space Design and Its Content The Meaning of Interior Space Design. Interior space design is a creative activity of human transformation of living space, through the interior space design can make human living environment become more comfortable [1]. Although the "interior space design" theory is not a long time, but has been constantly being human practice. Since ancient times, human beings have been in the pursuit of the security of living space. Full, comfortable and beautiful. People in the primitive society in the cave laying leaves, weeds and skins and in the walls of the cave with color drawing lines and patterns, and so on for living space transformation, which all belong to the indoor space design. Interior space design is not only focused on solving the relationship between people and nature, but also more and more focus on solving the problem of the relationship between people and society, so that people in the community better work and life. -

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space Martin Kilian Niloy J. Mitra Helmut Pottmann Vienna University of Technology Figure 1: Geodesic interpolation and extrapolation. The blue input poses of the elephant are geodesically interpolated in an as-isometric- as-possible fashion (shown in green), and the resulting path is geodesically continued (shown in purple) to naturally extend the sequence. No semantic information, segmentation, or knowledge of articulated components is used. Abstract space, line geometry interprets straight lines as points on a quadratic surface [Berger 1987], and the various types of sphere geometries We present a novel framework to treat shapes in the setting of Rie- model spheres as points in higher dimensional space [Cecil 1992]. mannian geometry. Shapes – triangular meshes or more generally Other examples concern kinematic spaces and Lie groups which straight line graphs in Euclidean space – are treated as points in are convenient for handling congruent shapes and motion design. a shape space. We introduce useful Riemannian metrics in this These examples show that it is often beneficial and insightful to space to aid the user in design and modeling tasks, especially to endow the set of objects under consideration with additional struc- explore the space of (approximately) isometric deformations of a ture and to work in more abstract spaces. We will show that many given shape. Much of the work relies on an efficient algorithm to geometry processing tasks can be solved by endowing the set of compute geodesics in shape spaces; to this end, we present a multi- closed orientable surfaces – called shapes henceforth – with a Rie- resolution framework to solve the interpolation problem – which mannian structure. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

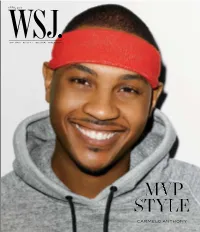

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Intelligent Design Is Not Science” Given by John G

An Outline of a lecture entitled, “Intelligent Design is not Science” given by John G. Wise in the Spring Semester of 2007: Slide 1 Why… … do humans have so much trouble with wisdom teeth? … is childbirth so dangerous and painful? Because a big, thinking brain is an advantage, and evolution is imperfect. Slide 2 Charles Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea His book changed the world. All life forms on this planet are related to each other through “Descent with modification over generations from a common ancestor”. Natural processes fully explain the biological connections between all life on the planet. Slide 3 Darwin’s Idea is Dangerous (from the book of the same title by Daniel Dennett) If we have evolution, we no longer need a Creator to create each and every species. Darwinism is dangerous because it infers that God did not directly and purposefully create us. It simply states that we evolved. Slide 4 Intelligent Design Attempts to Counter Darwin “Intelligent Design” has been proposed as way out of this dilemma. – Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, and Michael Behe (to name a few). They attempt to redefine science to encompass the supernatural as well as the natural world. They accept Darwin’s evolution, if an Intelligent Designer is (sometimes) substituted for natural selection. Design arguments are not new: − 1250 - St. Thomas Aquinas - first design argument − 1802 - Natural Theology - William Paley – perhaps the best(?) design argument Slide 5 What is Science? A specific way of understanding the natural world. Based on the idea that our senses give us accurate information about the Universe. -

Polanyi Review Committee Report

THE EXTERNAL REVIEW COMMITTEE REPORT BAYLOR UNIVERSITY The External Review Committee was convened to review the status of the Michael Polanyi Center at Baylor University, which was established a year ago with the primary aim of advancing the understanding of the sciences. In the early summer, members of the Committee received copies of books and articles relevant to the work of the Center. On September 8 and 9, 2000, the Committee met to discuss what they had read, to hear from persons who addressed matters about which the Committee was concerned, and to formulate a response to the charge the Committee had been given. The vigorous discussions about the issues contained in the charge reflected the variety in the backgrounds and perspectives of the Committee members. The outcome of these discussions was a thorough and even- handed review of the concerns before the Committee. It is important from the outset to emphasize that the sciences at Baylor University are the inheritors of a long and distinguished tradition. For many years, undergraduate instruction in the sciences at Baylor has been conducted in an exciting and effective manner. The graduate and research programs are solid and well respected throughout the scientific community. Not only have students and faculty been active in the mainstream of scientific disciplines, but they have also pursued initiatives in new areas and directions. Baylor’s heritage, in this regard, is clearly one of which it can be proud. The relationship of the sciences to other academic fields is a further responsibility that Baylor seeks to address. Relationships between the sciences and the humanities, as well as issues relating to the environment and public policy, are matters of real concern to the Baylor community. -

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution a Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused by Dr

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution A Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused By Dr. Mike Webster, Dept. of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University ([email protected]); February 2010 The current debate over evolution and “intelligent design” (ID) is being driven by a relatively small group of individuals who object to the theory of evolution for religious reasons. The debate is fueled, though, by misunderstandings on the part of the American public about what evolutionary biology is and what it says. These misunderstandings are exploited by proponents of ID, intentionally or not, and are often echoed in the media. In this booklet I briefly outline and explain 10 of the most common (and serious) misunderstandings. It is impossible to treat each point thoroughly in this limited space; I encourage you to read further on these topics and also by visiting the websites given on the resource sheet. In addition, I am happy to send a somewhat expanded version of this booklet to anybody who is interested – just send me an email to ask for one! What are the misunderstandings? 1. Evolution is progressive improvement of species Evolution, particularly human evolution, is often pictured in textbooks as a string of organisms marching in single file from “simple” organisms (usually a single celled organism or a monkey) on one side of the page and advancing to “complex” organisms on the opposite side of the page (almost invariably a human being). We have all seen this enduring image and likely have some version of it burned into our brains.