Matthew Dupuis Department of Art History F Ulfilment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Huguenots and Art, C. 1560–1685*

chapter 7 The Huguenots and Art, c. 1560–1685* Andrew Spicer 1 Introduction At an extraordinary meeting of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris on 10 October 1681, the president Charles Le Brun read a command from the king’s minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. On the orders of Louis xiv, those who were members of the Religion Prétendue Reformée were to be deprived of their positions within the Academy; their places were to be taken by Catholics, and membership in the future was to be restricted to this confes- sion. The measure particularly targeted seven men: Henri Testelin (1616–95), Secretary of the Academy; Jean Michelin (1623–96), Assistant Professor; Louis Ferdinand Elle, père (1612–89), Samuel Bernard (1615–87), Jacques Rousseau (1630–93), council members; Mathieu Espagnandel (1616–89) and Louis Ferdinand Elle fils (1648–1717), academicians. The secretary, Testelin, who had painted several portraits of the young king during the 1660s, acquiesced to the royal order but requested that the Academy recognize that he was deprived of his position not due to any personal failings concerning his honesty and good conduct. The academicians acknowledged this to be the case and similarly noted that the other Huguenots present—Bernard, Ferdinand Elle and Michelin—had acquitted their charge with probity and to the satisfaction of the company.1 The following January, the names of Jacob d’Agard and Nicolas Eude were struck from the Academy’s registers because they had both sought refuge in England.2 The expulsion of these artists and sculptors from this learned society was part of the increasing personal and religious restrictions imposed on the Huguenots by Louis xiv, which culminated in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in October 1685. -

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles Thomasf

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles ThomasF. Hedin It was Pierre Francastel who christened the most famous the west (Figs. 1, 2, both showing the expanded zone four program of sculpture in the history of Versailles: the Grande years later). We know the northern end of the axis as the Commande of 1674.1 The program consisted of twenty-four Allee d'Eau. The upper half of the zone, which is divided into statues and was planned for the Parterre d'Eau, a square two identical halves, is known to us today as the Parterre du puzzle of basins that lay on the terrace in front of the main Nord (Fig. 2). The axis terminates in a round pool, known in western facade for about ten years. The puzzle itself was the sources as "le rondeau" and sometimes "le grand ron- designed by Andre Le N6tre or Charles Le Brun, or by the deau."2 The wall in back of it takes a series of ninety-degree two artists working together, but the two dozen statues were turns as it travels along, leaving two niches in the middle and designed by Le Brun alone. They break down into six quar- another to either side (Fig. 1). The woods on the pool's tets: the Elements, the Seasons, the Parts of the Day, the Parts of southern side have four right-angled niches of their own, the World, the Temperamentsof Man, and the Poems. The balancing those in the wall. On July 17, 1664, during the Grande Commande of 1674 was not the first program of construction of the wall, Le Notre informed the king by statues in the gardens of Versailles, although it certainly was memo that he was erecting an iron gate, some seventy feet the largest and most elaborate from an iconographic point of long, in the middle of it.3 Along with his text he sent a view. -

OF Versailles

THE CHÂTEAU DE VErSAILLES PrESENTS science & CUrIOSITIES AT THE COUrT OF versailles AN EXHIBITION FrOM 26 OCTOBEr 2010 TO 27 FEBrUArY 2011 3 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles CONTENTS IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... 5 FOrEWOrD BY JEAN-JACqUES AILLAGON 7 FOrEWOrD BY BÉATrIX SAULE 9 PrESS rELEASE 11 PArT I 1 THE EXHIBITION - Floor plan 3 - Th e exhibition route by Béatrix Saule 5 - Th e exhibition’s design 21 - Multimedia in the exhibition 22 PArT II 1 ArOUND THE EXHIBITION - Online: an Internet site, and TV web, a teachers’ blog platform 3 - Publications 4 - Educational activities 10 - Symposium 12 PArT III 1 THE EXHIBITION’S PArTNErS - Sponsors 3 - Th e royal foundations’ institutional heirs 7 - Partners 14 APPENDICES 1 USEFUL INFOrMATION 3 ILLUSTrATIONS AND AUDIOVISUAL rESOUrCES 5 5 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... DISSECTION OF AN Since then he has had a glass globe made that ELEPHANT WITH LOUIS XIV is moved by a big heated wheel warmed by holding IN ATTENDANCE the said globe in his hand... He performed several experiments, all of which were successful, before Th e dissection took place at Versailles in January conducting one in the big gallery here... it was 1681 aft er the death of an elephant from highly successful and very easy to feel... we held the Congo that the king of Portugal had given hands on the parquet fl oor, just having to make Louis XIV as a gift : “Th e Academy was ordered sure our clothes did not touch each other.” to dissect an elephant from the Versailles Mémoires du duc de Luynes Menagerie that had died; Mr. -

Fw ^Ifjljtlintii \^Jfflti4rij the METROPOLITAN MUSEUM of ART

4 awfw ^ifjljtLintii \^Jfflti4rij THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Succeeding the majesty of the Sun King's reign, the courts oi Louis XV and XVI turned artistic canons from splendid pomp to the quintessence of grace. Charming refinements ruled manners and tastes throughout the eighteenth cen tury until, with the monarchy, they were overthrown and re placed by the austere classicism of Napoleon's Empire. Eighteenth-century art ists, many of whom de pended upon royal pa tronage, were masters at recording and popu larizing the balls and banquets, the theatrical per formances, the hunts and picnics that were the daily distractions of a pleasure-hungry court. Highly creative and receptive to a wide range of subject matter these artists found inspiration as readily on OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Mount Olympus as in the shepherd's bower or the rococo drawing room. A shift in interest from the lives of gods and heroes to the pleasures of contemporary life, particularly the delights of the privileged classes, is evident in the estampes galantes, elaborately engraved after designs by Moreau Le Jeune, Baudouin, and Lavreince. They are the most illuminating documents of aristocratic manners, of costume, and of the decoration of houses and palaces. These documents of not acquire original drawings. And reproduc worldly pleasures were complemented by a tions of paintings were produced by skilled pro vigorous academic tradition concerned with fessional engravers to meet the demands of an large-scale historical and mythological paint increasingly avid public. ing, splendidly exemplified in this exhibition Etching, a process more rapid and free by Carle Van Loo's large drawn model for a than engraving and in many ways akin to picture painted for Frederick the Great of drawing, provides some of the most interesting Prussia (no. -

The Portrait of the Sovereign

The Portrait of the Sovereign Painting as Hegemonic Practice in the Work and Discourse of Charles Le Brun and the Académie Royale de Peinture. Student: Nuno Atalaia Student Number: 1330004 Specialization: ResMA Arts and Culture Supervisor: Prof. dr. Frans-Willem Korsten Second Reader: Prof. dr.Yasco Horsman 1 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Painting as hegemonic practice ...................................................................................................... 4 Expanding discourse ........................................................................................................................ 6 Absolutism and Social Collaboration ............................................................................................. 11 The king’s portrait as icon ............................................................................................................. 14 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 17 Chapter I – Hegemony and Academic Strategy................................................................................. 19 Academic ambitions ...................................................................................................................... 21 Academic discourse ...................................................................................................................... -

Dossier Pédagogique | Charles Le Brun Created with Sketch

DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE 1 Exposition : Crédits photographiques : Commissariat : BÉNÉDICTE GADY, collaboratrice scientifique, département des Arts graphiques, musée du Louvre et h = haut Sommaire NICOLAS MILOVANOVIC, conservateur en chef, b = bas département des Peintures, musée du Louvre. g = gauche d = droite Directeur de la publication : m = milieu LUC PIRALLA, directeur par intérim, musée du Louvre-Lens Texte pédagogique : Charles Le Brun. Le peintre du Roi-Soleil Couverture : © Musée du Louvre / Marc Jeanneteau P. 4 : © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux Responsable éditoriale : P. 6 (h) : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado THÈME 1 : LE BRUN : PROTÉGÉ DES PUISSANTS 4 JULIETTE GUÉPRATTE, chef du service des Publics, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 6 (b) : © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin P. 7 : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Martine Beck-Coppola I. UN JEUNE ARTISTE DISTINGUÉ PAR SÉGUIER ET RICHELIEU 4 Coordination : P. 8 : © De Agostini Picture Library / G. Dagli Orti/Bridgeman Images EVELYNE REBOUL, en charge des actions éducatives, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 9 : © Collection du Mobilier national / Philippe Sébert II. LES PREMIÈRES ARMES AU SERVICE DE FOUQUET 5 P. 10 : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Droits réservés III. DE COLBERT À LOUIS XIV 6 Conception : P. 11 : © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Martine Beck-Coppola ISABELLE BRONGNIART, conseillère pédagogique en arts visuels, missionnée au P. 12 : © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski musée du Louvre-Lens P. 13 : © Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy / Bridgeman Images FLORENCE BOREL, médiatrice au musée du Louvre-Lens P. 15 (h) : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux THÈME 2 : LE BRUN : ARTISTE D’ENVERGURE 8 PEGGY GARBE, professeur d’arts plastiques au collège Henri Wallon de P. -

Jacques-Louis David: in Quest of a Hero

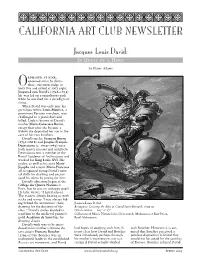

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER Jacques-Louis David: In Quest of a Hero by Elaine Adams rphaned at nine, esteemed artist by thirty- Othree, execution judge at forty-five and exiled at sixty-eight; Jacques-Louis David’s (1748–1825) life was led on a tumultuous path while he searched for a paradigm of virtue. When David was only nine his garrulous father, Louis-Maurice, a prominent Parisian merchant, was challenged to a pistol duel and killed. Little is known of David’s mother Marie-Geneviève Buron, except that after she became a widow she deposited her son in the care of her two brothers. David’s uncles, François Buron (1731–1818) and Jacques-François Desmaisons (c. 1720–1789) were both master masons and architects; Desmaisons was a member of the Royal Academy of Architecture and worked for King Louis XVI. His uncles, as well as his aunt Marie- Josephe and cousin Marie-Francoise all recognized young David’s natu- ral skills for drawing and encour- aged his talent by posing for him. David’s education began at the Collège des Quatre Nations in Paris, but he was an unhappy pupil. He later wrote, “I hated school. The masters always beating us with sticks and worse. I was always hid- ing behind the instructors’ chair, Jacques-Louis David drawing for the duration of the Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard, 1800-01 class.” David’s uncles decided to Oil on canvas 103Љ ϫ 87Љ send him to the medieval painter’s Collection of Musée National des Châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau, guild Académie de Saint-Luc for Reuil-Malmaison drawing classes. -

Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis Xiv

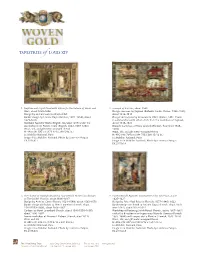

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: December 1, 2015 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Amy Hood Getty Communications (310) 440-6427 [email protected] GETTY MUSEUM PRESENTS WOVEN GOLD: TAPESTRIES OF LOUIS XIV Exhibition is the first major tapestry show in the Western U.S. in four decades Woven Gold amongst a series of exhibitions and special installations at the Getty marking the 300th anniversary of the death of Louis XIV December 15, 2015 – May 1, 2016 at the Getty Center Autumn, before 1669, Gobelins Manufactory (French, 1662 - present). Cartoon attributed to Beaudrin Yvart (French, 1611 - 1690), after Charles Le Brun (French, 1619- 1690). Tapestry, wool, silk and gilt metal-wrapped thread. Le Mobilier National, France. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis LOS ANGELES – The art of tapestry weaving in France blossomed during the reign of Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715). Three hundred years after the death of France’s so-called “Sun King,” the J. Paul Getty Museum will showcase 14 monumental tapestries from the French royal collection, revealing the stunning beauty and rich imagery of these monumental works of art. Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV, exclusively on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center from December 15, 2015 through May 1, 2016, will be the first major museum exhibition of tapestries in the western United States in four decades. -more- Page 2 “Under Louis XIV, tapestry production flourished in France as never before, with the Crown’s tapestry collection growing to be the greatest in early modern Europe,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. -

Press Image Sheet

1. Neptune and Cupid Plead with Vulcan for the Release of Venus and 2. Triumph of Bacchus, about 1560 Mars, about 1625–1636 Design overseen by Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio, Italian, 1483–1520), Design by an Unknown Northern Artist about 1518–1519 Border design by Francis Cleyn (German, 1582–1658), about Design and cartoon by Giovanni da Udine (Italian, 1487–1564) 1625–1628 in collaboration with other artists from the workshop of Raphael, Mortlake Tapestry Works (English, founded 1619) under the about 1518–1520 ownership of Sir Francis Crane (English, about 1579–1636) Brussels workshop of Frans Geubels (Flemish, flourished 1545– Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread 1585) H: 440 x W: 585 cm (173 1/4 x 230 5/16 in.) Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread Le Mobilier National, Paris H: 495 x W: 764 cm (194 7/8 x 300 13/16 in.) Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis Le Mobilier National, Paris EX.2015.6.3 Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis EX.2015.6.4 3. The Chariot of Triumph Drawn by Four Piebald Horses (also known 4. Constantius [I] Appoints Constantine as his Successor, about as The Golden Chariot), about 1606–1607 1625–1627 Design by Antoine Caron (French, 1521–1599), about 1563–1570 Design by Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), 1622 Border design attributed to Henri Lerambert (French, about Border design attributed to Laurent Guyot (French, about 1575– 1540/1550–1608), about 1606–1607 after 1644), about 1622–1623 Cartoon by Henri Lerambert (French, about 1540/1550–1608), Workshop of Faubourg Saint-Marcel (French, active 1607–1661) about 1606–1607 under the direction of entrepreneurs Marc de Comans (Flemish, Louvre workshop of Maurice I Dubout (French, died 1611) 1563–1644) and François de La Planche (Flemish, 1573–1627) Wool and silk Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread H: 483 x W: 614 cm (190 3/16 x 241 3/4 in.) H: 458 x W: 407 cm (180 5/16 x 160 1/4 in.) Le Mobilier National, Paris Le Mobilier National, Paris Image © Le Mobilier National. -

Artistes, Collections Et Musees Un Hommage a Antoine Schnapper

Centre André Chastel, Paris-Sorbonne Centre André Chastel, Paris-Sorbonne Centre André Chastel, Paris-Sorbonne ARTISTES, COLLECTIONS ET MUSEES INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES UN HOMMAGE A ANTOINE SCHNAPPER INHA, SALLE VASARI Galerie Colbert, 2 rue Vivienne, 75002 Paris. Artistes, collections et musées. Le propos de ce colloque est de Métro Palais-Royal, Bourse, Pyramides (L. 1, 3, 7 et 14) rendre hommage, en étudiant l’actualité de sa démarche historique, à la carrière scientifique d’Antoine Schnapper (1933-2004), professeur d’histoire de l’art moderne à Paris IV Sorbonne. Les principaux sujets qu’aborderont tant ses anciens collègues et disciples que des chercheurs attentifs aux mêmes thèmes que lui toucheront aux domaines de l’histoire de l’Art qu’il a le plus contribué à développer ou à renouveler. Deux sessions seront consacrées à l’histoire des collections qu’il a enrichie de deux ouvrages, devenus des classiques, sur les e collections françaises du XVII siècle, Le géant, la licorne et la tulipe, Flammarion, 1988 et Curieux du Grand Siècle, Flammarion, 1994 (rééd. Champs, 2005). Plusieurs contributions se situent dans la lignée de son dernier ouvrage, Le métier de peintre au Grand Siècle, Gallimard, 2004, et aborderont le fonctionnement de la production artistique comme l’économie de l’art. Une CENTRE ANDRE CHASTEL session spécifique permettra de faire le point sur les nouvelles Laboratoire de recherche sur le patrimoine français et l’histoire de l’art découvertes et approches de l’œuvre peint et dessiné de occidental (Université de Paris-Sorbonne - CNRS - MCC). Jacques-Louis David depuis sa grande monographie sur l’artiste Institut national d’histoire de l’art, (1980) et l’exposition rétrospective (1989) dont il fut l’un des 2 rue Vivienne, Galerie Colbert, deux commissaires. -

Exhibition Checklist Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis Xiv

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST WOVEN GOLD: TAPESTRIES OF LOUIS XIV At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center December 15, 2015 – May 1, 2016 In the hierarchy of court art, tapestry was regarded, historically, as the preeminent expression of princely status, erudition, and aesthetic sophistication. Extraordinary resources of time, money, and talent were allocated to the creation of these works meticulously woven by hand with wool, silk, and precious- metal thread, after designs by the most esteemed artists. The Sun King, Louis XIV of France (born 1638; reigned 1643–1715), formed the greatest collection of tapestries in early modern Europe. By the end of his reign, the assemblage was staggering, totaling some 2,650 pieces. Though these royal hangings were subsequently dispersed, the largest, present repository of Louis’s holdings is the Mobilier National of France. With rare loans from this prestigious institution, Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV explores and celebrates this spectacular accomplishment. This exhibition was organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum in association with the Mobilier National et les Manufactures Nationales des Gobelins, de Beauvais et de la Savonnerie. We gratefully acknowledge the Hearst Foundations, Eric and Nancy Garen, and the Ernest Lieblich Foundation for their generous support. Catalogue numbers refer to Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV by Charissa Bremer-David, published by The J. Paul Getty Museum numbers refer to the GettyGuide® audio tour Louis XIV as Collector, Heir, Patron By the end of Louis XIV’s reign, the French Crown’s impressive holdings of tapestries had grown by slow accumulation over centuries and by intense phases of opportunistic acquisition and strategic patronage. -

Louis XIII (1610-1643) Richelieu As Chief Minister

French Monarchy – Dynastic change from Valois to Bourbon 16th Century – French Wars of Religion 1562-1589 sons of Henry II and Catherine de Medici become the last of the Valois Kings of France 1589 – Wars of Religion end with victory of Henry IV, Bourbon Prince of Navarre 1589-1610 (assassinated) start of the Bourbon dynasty (through French Revolution) married to Marie de Medici, who becomes Regent for son Louis XIII (1610-1643) Richelieu as Chief Minister Louis XIV (1643-1715) Mazarin as Chief Minister (died 1661) then personal rule of the King Louis XIII in 1611 After his father’s death in 1610 Cardinal Richelieu 1637 Chief minister to Louis XIII Armand Jean du Plessis Portrait by Phillipe de Champaigne Richelieu 1640 Triptych Bust of Cardinal Richelieu by Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1641 Louis XIII 1610-1643 Phillipe de Champaigne The Fronde (1648 -1653) The Fronde Fronde (slingshot) was the name given to that faction; I will give you the etymology of it….. Someone once said, in jest, that the Parlement of Paris acted like the schoolboys, who fling stones, and run away when they see the constable, but meet again as soon as he turns his back. This was thought a very apt comparison. It came to be a subject for ballads, and, upon the peace between the King and Parlement, it was revived and applied to those who still did not agree with the Court …. We therefore resolved that night to wear hatbands made in the form of a sling, and had a great number of them made ready to be distributed….