Points of Transition: Ritual Remaking of Religious, Ecological, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

An Observation and Analysis of Mongolia's

Saldarriaga 1 Spirituality in Limbo: An Observation and Analysis of Mongolia’s Modern Religious Climate Dustin Saldarriaga Academic Director: Ulziijargal Sanjaasuren Hirgis Munkh-Ochir (Advisor) School for International Training: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Fall 2004 Saldarriaga 2 Dedicated to Mom, Al, and Jason for giving me the curiosity, courage, and opportunity to travel across the world to a country they had heard of only in legends. Saldarriaga 3 I would like to thank… Delgermaa for her wonderful and consistent work as my translator who never hesitated to share Tsetserleg with me. The various individuals throughout the semester who shared their homes with me and made my experience truly unique and amazing. A special “thank you” goes to Tomorbaatar, Enkhtuya, and Bilguun for sharing their beautiful home and putting up with me for well over a month in UB. Bat-Gerel and Pastor Bayraa, who shared with me the passion and love behind the religions to which they dedicated their lives—a simple “thank you” is just not enough. Dashzeveg and Bulganchimeg, who made my time in Tsetserleg possible through their time and help. It was comforting to know they were always just a phone call away. Professor Munkh-Ochir, who always gave me new ideas or perspectives to consider, whether through his lectures, readings, or advice. Mom Ulzii, Pop Ulzii, Baatar, Saraa, Ariuna, TJ, and Inghe, who provided me with wonderful assistance, preparations, and opportunities. It’s not appropriate to try to summarize in a tiny paragraph the assistance and contributions you all shared over the course of the semester. I am grateful, to say the least. -

Mongolian Cultural Orientation

Table of Contents Chapter 1: Profile ............................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 Geography ................................................................................................................................... 6 Area ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Climate .................................................................................................................................... 7 Geographic Divisions and Topographic Features ................................................................... 8 Rivers and Lakes ..................................................................................................................... 9 Major Cities ............................................................................................................................... 10 Ulaanbaatar ............................................................................................................................ 10 Erdenet ................................................................................................................................... 11 Darhan .................................................................................................................................. -

Nature, Culture, and Shamanism in Inner Mongolia, PRC

EnviroLab Asia Volume 3 Issue 3 Mongolia Article 2 2-2020 Afterthoughts: Nature, Culture, and Shamanism in Inner Mongolia, PRC Hao Huang Scripps College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia Part of the Asian History Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Geography Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Huang, Hao (2019) "Afterthoughts: Nature, Culture, and Shamanism in Inner Mongolia, PRC," EnviroLab Asia: Vol. 3: Iss. 3, Article 2. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia/vol3/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in EnviroLab Asia by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Huang: Nature, Culture, and Shamanism in Inner Mongolia, PRC Afterthoughts: Nature, Culture, Music, and Shamanism in Inner Mongolia, PRC Hao Huang1 Introduction The autonomous region of Inner Mongolia in northern China encompasses nearly half a million square miles and is inhabited by about twenty five million people. It is a narrow strip of land that stretches 1500 miles from west to east, and 1000 miles north to south, bordering both Mongolia and Russia. Indigenous Mongolians make up about 18 per cent of the population, which is predominantly Han Chinese. Although three quarters of the Mongolian population live in cities, the grasslands endure as symbols of traditional Mongolian values. Yurts (gers in Mongolian language), traditionally made of felt cloth over a wooden framework, persist as nostalgic icons of nomadic Mongolian lifestyle. -

Research on Economic Corridor Mongolia- Russia-China

“RESEARCH ON ECONOMIC CORRIDOR MONGOLIA- RUSSIA-CHINA” Possibility to advance the economic corridor program implementation THE MONGOLIAN INSTITUTE FOR SINOLOGY DEVELOPMENT “RESEARCH ON ECONOMIC CORRIDOR MONGOLIA-RUSSIA-CHINA” Possibility to advance the economic corridor program implementation 2020 The Mongolian Institute for Sinology Development 2019 The Mongolian Institute for Sinology development #407, Tanan center, 14192 Ulaanbaatar Telephone: 976-99070579 Email: [email protected] EU – Trade Related Assistance for Mongolia Project (EU TRAM) Peace Avenue-7A, Ulaanbaatar 14210, Mongolia Tel: (976)-70008160, 70008162 e-mail: [email protected] www.tram-mn.eu EU Disclaimer The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the Consultant and in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This project is funded by the European Union. Acknowledgements A research report entitled “Opportunities to push forward the implementation of the Economic Corridor Program” has been prepared at the initiative of T.Battsetseg, Deputy Director of the Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia. This research report has been compiled by B.Indra, Ph.D., founder and researcher of the Mongolian Institute for the Sinology Development, Ts.Davaadorj, Ph.D., researcher, and B.Dulguun, researcher. Our deepest gratitude and thanks go to Carmen Fratita, Team Leader of the European Union Trade Related Assistance for Mongolia (TRAM), as well as the entire project team for their support in preparation of this research report. We would also like to thank the staff of the Department of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia for their continuous support and cooperation in guiding and collecting the information necessary for the preparation of the research report. -

Chinggis Khan: Ancestor, Buddha Or Shaman? Isabelle Charleux

Chinggis Khan: Ancestor, Buddha or Shaman? Isabelle Charleux To cite this version: Isabelle Charleux. Chinggis Khan: Ancestor, Buddha or Shaman?: On the uses and abuses of the portrait of Chinggis Khan. Mongolian studies, The Mongolian society, Bloomington (Indiana, Etats- Unis), 2009, 31, pp.207-258. halshs-00613828 HAL Id: halshs-00613828 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00613828 Submitted on 6 Aug 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isabelle Charleux, «Chinggis Khan: Ancestor, Buddha or Shaman? » Author’s own file, not the published version. Please see the published version, Mongolian Studies , 31 (2009), 207-258 Chinggis Khan: Ancestor, Buddha or Shaman? On the uses and abuses of the portrait of Chinggis Khan 1 Isabelle Charleux CNRS, Groupe Religions, Sociétés, Laïcités Paris, France The perception of Chinggis Khan by Mongols, Chinese, Central Asians and Europeans has already been discussed by several scholars, 2 but the visual representations corresponding to the different narratives developed by them have not yet attracted much attention. However, studying the visual images of Chinggis Khan can tell us much about the nature of his cult and the messages the various authorities that manipulated it aimed to convey. -

Normative Research on English Translation of Tourist Attractions in Inner Mongolia

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 2, Issue 11: 01-07, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2020.021101 Normative Research on English Translation of Tourist Attractions in Inner Mongolia Yaoyao Gao Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot 010010, China ABSTRACT. At present, the standardized development of tourist attractions in China is not mature enough. Taking the normative situation of English translation of tourist attractions in Inner Mongolia as an example, some English translation anomies appear. Moreover, many tourist attractions in Inner Mongolia are endowed with profound Mongolian culture. The translation in the English version is not obvious, and even brings tourists a difficult and incomprehensible feeling, from which it is difficult to understand the characteristic ethnic culture and folk customs contained in the tourist attractions in Inner Mongolia. Based on this, in this article, the author will summary some differentiations of the tourist attractions in the English translation, taking the skopos theory as the theoretical foundation and the tourist attractions in Inner Mongolia autonomous region as the case study to hope that customs and cultures in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region has spread far and wide, and promoted the overall development level of tourism in Inner Mongolia. KEYWORDS: Tourist attractions, English translation, Normative translation, Skopos theory, Amplification, Omission 1. Introduction The English translation of tourist attractions is not only the introduction of tourist attractions, but the publicity of tourist attractions, tourist signs, folk customs, explanations and other aspects. In the process of translation, it is not only necessary to convey the information of the original text, but more importantly, to effectively convey the information of the original text to the readers of the target language in an easy-to-understand language. -

The Making of Mongol Buddhist Art and Architecture Isabelle Charleux

The Making of Mongol Buddhist Art and Architecture Isabelle Charleux To cite this version: Isabelle Charleux. The Making of Mongol Buddhist Art and Architecture: Artisans in Mongolia from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Elvira Eevr Djaltchinova-Malets. Meditation. The art of Zanabazar and his school, catalogue trilingue (polonais, anglais, mongol) de exposition éponyme organisée au Asia and Pacific Museum, The Asia and Pacific Museum, p. 59-105, 2010. halshs- 00702140 HAL Id: halshs-00702140 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00702140 Submitted on 10 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isabelle Charleux, « The Making of Mongol Buddhist Art and Architecture: Artisans in Mongolia from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century » - Author’s own file, not the published version. Please see the published version in Meditation. The Art of Zanabazar and his School, Elvira Eevr Djaltchinova-Malets (ed.), Varsovie, Varsovie : The Asia and Pacific Museum, 2010, p. 59-105. The Making of Mongol Buddhist Art and Architecture: Artisans -

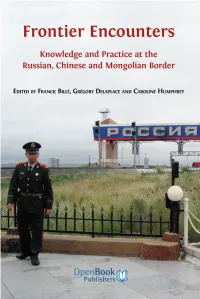

Frontier Encounters: Knowledge and Practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/139 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. The Russia-China-Mongolia border FRONTIER ENCOUNTERS Knowledge and Practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border Edited by Franck Billé, Grégory Delaplace and Caroline Humphrey http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Franck Billé, Grégory Delaplace and Caroline Humphrey (contributors retain copyright of their work). Version 1.1. Minor edits made, July 2013. This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Billé, Franck, Delaplace, Grégory and Humphrey, Caroline (eds.) Frontier Encounters: Knowledge and Practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2012. DOI: 10.11647/ OBP.0026 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781906924874 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-906924-88-1 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-906924-87-4 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-906924-89-8 ISBN Digital ebook (epub version): 978-1-906924-90-4 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi version): 978-1-906924-91-1 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0026 Cover image: Chinese frontier guard at the Manzhouli-Zabaikalsk border by John S.Y. -

The Revival of Mongolian Shamanism in China’S Inner Mongolia

International JournalRevival of China of Mongolian Studies Shamanism in China’s Inner Mongolia 319 Vol. 11, No. 2, December 2020, pp. 319-343 Healing Practices Regenerate Local Knowledge: The Revival of Mongolian Shamanism in China’s Inner Mongolia Saijirahu Buyanchugla* Inner Mongolia University for the Nationalities, Tongliao, China Abstract Shamanistic healing practices, including divination, have coexisted with other religious and medical practices in modern Inner Mongolia and China for many years. However, scholarly research has yet to investigate the effectiveness of shamanic healing and its physical and psychological benefits. This paper discusses the practice of shamanic activities, including healing rituals, on the boundaries between the spiritual communities and the masses in Eastern Inner Mongolia, and how the contrasts between the perspectives of healers or practitioners and the lay people’s more fluid understanding of the practices impact health, illness, and ethnic/cultural identity. Why is it that shamanistic healing is not included in any of the official healing systems, despite its importance as a health resource and as a factor in identity formation in Inner Mongolia. This study will show that shamanistic healing is not included in the official healing systems due to several historical forces and geopolitical events, such as the invasion of exotic cultures and China’s ban on religious activities during and after the 1940s, when land reform, socialist trans- formation policies, and the Cultural Revolution took hold in Inner Mongolia. In addition, the official recognition of Mongolian medicine as a national medicine in the 1960s left no room for other local healing practices, including shamanistic healing. -

Mongolian Buddhists Protecting Nature

Mongolian Buddhists Protecting Nature Mongolian Buddhists Protecting Nature A Handbook on Faiths, Environment and Development by Urantsatsral Chimedsengee, Amber Cripps, Victoria Finlay, Guido Verboom, Ven Munkhbaatar Batchuluun, Ven Da Lama Byambajav Khunkhur This publication was funded by NEMO (Netherlands Mongolia Trust Fund on Environmental Reform-II) at the World Bank, and was created by ARC (Alliance of Religion and Conservation) in partnership with Gandan Tegchenling Monastery, MNET, (Mongolian Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism), and TTF (The Tributary Fund). It was produced and translated into Mongolian by Gandan Tegchenling Monastery (the Centre of Mongolian Buddhism), supported by MNET, Mongolia. Published in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia First printing January 2009 This edition is also published in Mongolian Mongolian Buddhists Protecting Nature DDC 294.337 V-59 © The Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC) The House Kelston Park Bath BA1 9AE UK Telephone 44 1225 758004 Internet www.arcworld.org Rights and permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. However, the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC) encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to The Alliance of Religions and Conservation, The House, Kelston Park, Bath BA1 9AE, UK, or email to -

Copy of Iams News

January 2019 Volume 1 IAMS NEWS LATEST NEWS ON MONGOL STUDIES January 2019 LATEST NEWS ON MONGOL STUDIES Volume 2 “GENGHIS KHAN” EXHIBITION OPENS IN MOBILE CITY, ALABAMA, THE USA January 25, 2019- April 26, 2019 “Chinggis Khaan: The Great Civilizer” As the exhibit strikingly portrays, exhibition, which demonstrates Chinggis Genghis’s reputation as the greatest Khaan and the Mongol Empire, was conqueror is well-deserved – he launched in the City of Mobile, Alabama, dominated three times more land in his US. lifetime than either Julius Caesar or Curated and developed by dinosaur Alexander the Great, a conquest expert Don Lessem, the exhibition attested to by the formidable array of features more than 300 spectacular swords, bows, arrows, saddles and objects on display, including rare and armor included on display in Genghis sophisticated weapons, costumes, jewels, Khan. In fact, the historic exhibition ornaments, instruments and numerous showcases hundreds of artifacts from other fascinating relics and elaborate Genghis’s 13th century Empire, the artifacts from 13th-century Mongolia. largest such collection ever to tour. Experience life in 13th-century Mongolia, Visitors will experience the exhibition entering the tents, battlegrounds and through the eyes of a Mongolian marketplaces of a vanished world that resident, receiving a civilian identity card was once the largest land empire in at the beginning of their journey. From history. Explore Genghis Khan’s life and warrior to spy to princess, they will those of his sons and grandsons during follow this character’s life throughout the formation, peak and decline of the the rise of the great Mongol Empire Mongol Empire.