A Preliminary Revision of the Sino-Himalayan Whitebeams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury

DETECTING SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE INJURY TRAINING GUIDE Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury TRAINING GUIDE Jozef Ric1, Peter de Groot2, Ben Gasman3, Mary Orr3, Jason Doyle1, Michael T Smith4, Louise Dumouchel3, Taylor Scarr5, Jean J Turgeon2 1 Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation 2 Natural Resources Canada - Canadian Forest Service 3 Canadian Food Inspection Agency 4 United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service 5 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources We dedicate this guide to our spouses and children for their support while we were chasing this beetle. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury : Training / Jozef Ric, Peter de Groot, Ben Gasman, Mary Orr, Jason Doyle, Michael T Smith, Louise Dumouchel, Taylor Scarr and Jean J Turgeon © Her Majesty in Right of Canada, 2006 ISBN 0-662-43426-9 Cat. No. Fo124-7/2006E 1. Asian longhorned beetle. 2. Trees- -Diseases and pests- -Identification. I. Ric, Jozef II. Great Lakes Forestry Centre QL596.C4D47 2006 634.9’67648 C2006-980139-8 Cover: Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) adult. Photography by William D Biggs Additional copies of this publication are available from: Publication Office Plant Health Division Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Canadian Food Inspection Agency Great Lakes Forestry Centre Floor 3, Room 3201 E 1219 Queen Street East 59 Camelot Drive Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario CANADA P6A 2E5 CANADA K1A 0Y9 [email protected] [email protected] Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre: Détection des signes et symptômes d’attaque par le longicorne étoilé : Guide de formation. -

Choosing the Right Tree to Plant

Prunus / Cherry flower Choosing the right tree to plant Choosing what tree to plant can be difficult with the buildings, shading, overhanging roads and footpaths number of different species, cultivars and varieties that etc.? It may not be sensible to replace a large forest are currently available. There are a number of useful type tree in a small domestic garden with another one books and websites, but if you are still unsure it may be unless you are prepared to remove it before it outgrows useful to visit a garden or arboretum. There are some its situation. basic points that should be considered as follows. Benefits - as well as having obvious ornamental Soil - will the tree grow well in the soil in which is to be attributes, trees provide shelter, reduce temperature planted? Acidity, drainage and the type of soil will all extremes and produce oxygen. have a bearing. Some tree species are more specific than others as to their requirements. Once you have decided on your tree, the next step is to purchase it. Please bear in mind that if you have Local distinctiveness - what species grow naturally in removed a protected tree (that is one growing in a the area already? Native species are usually best for conservation area or subject to a tree preservation wildlife and ‘fit in’ with the landscape character and are order) there may either be a duty (as in the case of normally preferable to ornamental species. dead or dangerous trees) or a condition (in the case of a tree preservation order application) requiring the Available space - is the tree able to reach its full planting of a replacement tree. -

Fruits: Kinds and Terms

FRUITS: KINDS AND TERMS THE IMPORTANT PART OF THE LIFE CYCLE OFTEN IGNORED Technically, fruits are the mature ovaries of plants that contain ripe seeds ready for dispersal • Of the many kinds of fruits, there are three basic categories: • Dehiscent fruits that split open to shed their seeds, • Indehiscent dry fruits that retain their seeds and are often dispersed as though they were the seed, and • Indehiscent fleshy fruits that turn color and entice animals to eat them, meanwhile allowing the undigested seeds to pass from the animal’s gut We’ll start with dehiscent fruits. The most basic kind, the follicle, contains a single chamber and opens by one lengthwise slit. The columbine seed pods, three per flower, are follicles A mature columbine follicle Milkweed seed pods are also large follicles. Here the follicle hasn’t yet opened. Here is the milkweed follicle opened The legume is a similar seed pod except it opens by two longitudinal slits, one on either side of the fruit. Here you see seeds displayed from a typical legume. Legumes are only found in the pea family Fabaceae. On this fairy duster legume, you can see the two borders that will later split open. Redbud legumes are colorful before they dry and open Lupine legumes twist as they open, projecting the seeds away from the parent The bur clover modifies its legumes by coiling them and providing them with hooked barbs, only opening later as they dry out. The rattlepods or astragaluses modify their legumes by inflating them for wind dispersal, later opening to shed their seeds. -

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar SORBUS FAJKELETKEZÉS TRIPARENTÁLIS HIBRIDIZÁCIÓVAL A KELET- ÉS DÉLKELET- EURÓPAI TÉRSÉGBEN (Nothosubgenus Triparens) Doktori (PhD) értekezés Németh Csaba BUDAPEST 2019 A doktori iskola megnevezése: Kertészettudományi Doktori Iskola tudományága: Növénytermesztési és kertészeti tudományok vezetője: Zámboriné Dr. Németh Éva egyetemi tanár, DSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Gyógy- és Aromanövények Tanszék Témavezető: Dr. Höhn Mária egyetemi docens, CSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Növénytani Tanszék és Soroksári Botanikus Kert A jelölt a Szent István Egyetem Doktori Szabályzatában előírt valamennyi feltételnek eleget tett, az értekezés műhelyvitájában elhangzott észrevételeket és javaslatokat az értekezés átdolgozásakor figyelembe vette, azért az értekezés védési eljárásra bocsátható. .................................................. .................................................. Az iskolavezető jóváhagyása A témavezető jóváhagyása 2 Édesanyám emlékének. 3 4 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK RÖVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE .......................................................................................................... 7 1. BEVEZETÉS ÉS CÉLKITŰZÉS .................................................................................................. 9 2. IRODALMI ÁTTEKINTÉS ..................................................................................................... 11 2.1. A Sorbus nemzetség taxonómiai vonatkozásai .................................................................... -

The Buffer Handbook Plant List

THE BUFFER HANDBOOK PLANT LIST Originally Developed by: Cynthia Kuhns, Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates With funding provided by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Maine Department of Environmental Protection,1998. Revised 2001 and 2009. Publication #DEPLW0094-B2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 1 Introductory Information Selection of Plants for This List 1 Plant List Organization & Information 3 Terms & Abbreviations 4 Plant Hardiness Zone Map 5 General Tree & Shrub Planting Guidelines 5 Tips for Planting Perennials 7 Invasive Plants to Avoid 7 Plant Lists TREES 8 (30 to 100 ft.) SHRUBS 14 Small Trees/Large Shrubs 15 (12 to 30 ft.) Medium Shrubs 19 (6 to 12 ft.) Small Shrubs 24 (Less than 6 ft.) GROUNDLAYERS 29 Perennial Herbs & Flowers 30 Ferns 45 Grasses 45 Vines 45 References 49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Original Publication: This plant list was published with the help of Clean Water Act, Section 319 funds, under a grant awarded to the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District and with help from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Graphics and ‘clip-art’ used in this document came from the University of Wisconsin-Extension and from Microsoft Office 97(Small Business Edition) and ClickArt 97 (Broderbund Software, Inc). This publication was originally developed by Cynthia Kuhns of Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates. Substantial assistance was received from Phoebe Hardesty of the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District. Valuable review and advice was given by Karen Hahnel and Kathy Hoppe of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. Elizabeth T. Muir provided free and cheerful editing and botanical advice. -

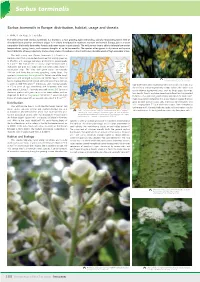

Sorbus Torminalis

Sorbus torminalis Sorbus torminalis in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats E. Welk, D. de Rigo, G. Caudullo The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a fast-growing, light-demanding, clonally resprouting forest tree of disturbed forest patches and forest edges. It is widely distributed in southern, western and central Europe, but is a weak competitor that rarely dominates forests and never occurs in pure stands. The wild service tree is able to tolerate low winter temperatures, spring frosts, and summer droughts of up to two months. The species often grows in dry-warm and sparse forest habitats of low productivity and on steep slopes. It produces a hard and heavy, durable wood of high economic value. The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a medium-sized, fast-growing deciduous tree that usually grows up to 15-25 m with average diameters of 0.6-0.9 m, exceptionally Frequency 1-3 < 25% to 1.4 m . The mature tree is usually single-stemmed with a 25% - 50% distinctive ash-grey and scaly bark that often peels away in 50% - 75% > 75% rectangular strips. The shiny dark green leaves are typically Chorology 10x7 cm and have five to nine spreading, acute lobes. This Native species is monoecious hermaphrodite, flowers are white, insect pollinated, and arranged in corymbs of 20-30 flowers. The tree Yellow and red-brown leaves in autumn. has an average life span of around 100-200 years; the maximum (Copyright Ashley Basil, www.flickr.com: CC-BY) 1-3 is given as 300-400 years . -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Native Woodland.Indd

Scottish Borders NATIVE WOODLAND HABITAT ACTION PLAN NATIVE WOODLAND in the Scottish Borders The status and ecology of native Native woodlands have, for the woodland in the Borders purposes of classification and assessment by government agencies The principle aim of the Scottish Borders such as SNH, been divided into a HAP for native woodlands is to maintain, number of different categories: enhance and expand in area the native woodlands of the Scottish Borders. 1. Ancient woodland - woodland present on maps pre 1750 Native woodlands are defined as 2. Long established woodland - ‘woodlands composed wholly or largely woodland present on maps pre 1850 of the tree species which occur naturally 3. Semi-natural woodland - woodland in the Scottish Borders; including both that has developed through self woodlands with a continuous history seeding of natural regeneration and those where either the current or a previous Semi-natural woodland in the Borders generation of trees has been planted is sparse and totals approximately within their natural range’. 6,790ha. The distribution of ancient and semi-natural woodland within Throughout Great Britain there has been the Borders is interesting: Berwickshire a gradual decline in the remaining contains the largest hectarage of native woodland, with a reduction of ancient and semi-natural woodland approximately 30 - 40% over the last 60 with 298ha (0.4% of land area), Ettrick years. This decline has mostly been due and Lauderdale contain 225ha (0.2% of to: land area), Roxburgh has 180ha (0.1%of land area) and Tweeddale has only 1. The conversion of native woodland to 35ha (<0.1% of land area) (Walker & agricultural land Badenoch 1988, 1989 and 1991). -

Plant Anatomy Lab 13 – Seeds and Fruits

Plant Anatomy Lab 13 – Seeds and Fruits In this (final) lab, you will be observing the structure of seeds of gymnosperms and angiosperms and the fruits of angiosperms. Much of the work will be done with a dissecting microscope, but a few prepared slides will also be used. A set of photocopied images from the plant anatomy atlas will be available as a handout. You can use the handout to help you identify the various structures we will be looking at in seeds and fruits. Also, a fruit key is available as a separate handout. Remember that we will be considering only a small fraction of the structural diversity present among seeds of gymnosperms and the seeds and fruits of angiosperms. Seeds Gymnosperms Obtain a prepared slide of an immature pine ovule and of a mature pine ovule. You will be able to tell them apart from the following observations. • Looking at the immature ovule, you will see a megagametophyte with one or more archegonia at the end near the micropyle. The egg inside may or may not have been fertilized. • Also find the nucellus and integument tissues. Next look at a slide of a mature ovule. Instead of the megagametophyte, you will find a developing embryo. As part of this embryo, find the • cotyledons, • the radicle (embryonic root), and the • shoot apical meristem. Depending on its age, you may also notice procambial strands running between the embryonic root and the shoot apex. Points to consider: We might say that gymnosperms and angiosperms have seeds but only angiosperms have fruits - Why is that? Why don’t we consider the seed cone of a pine tree a fruit? Angiosperms Dicot Obtain a bean pod. -

Landscaping Without Harmful Invasive Plants

Landscaping without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation Landscaping charity Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are without less likely to cause problems to the environment harmful should they escape from your planting area. Even the most careful land managers cannot invasive ensure that their plants do not escape and plants establish in nearby habitats (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. A few popular landscaping plants can cause problems for you / your clients and the environment. These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they comprise a small Under the Wildlife and Countryside minority of the 70,000 or so plant varieties available, the Act, it is an offence to plant, or cause to damage they can do is extensive and may be irreversible. grow in the wild, a number of invasive ©Trevor Renals ©Trevor non-native plants. Government also has powers to ban the sale of invasive Some invasive non-native plants might be plants. At the time of producing this straightforward for you (or your clients) to keep in booklet there were no sales bans, but check if you can tend to the planted area often, but it is worth checking on the websites An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a in the wider countryside, where such management river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can below to fi nd the latest legislation is not feasible, these plants can establish and cause cause water to appear as solid ground. -

Tically Expands Our Understanding on Virosphere in Temperate Forest Ecosystems

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 21 June 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202106.0526.v1 Review Towards the forest virome: next-generation-sequencing dras- tically expands our understanding on virosphere in temperate forest ecosystems Artemis Rumbou 1,*, Eeva J. Vainio 2 and Carmen Büttner 1 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, Albrecht Daniel Thaer-Institute of Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Ber- lin, Germany; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Natural Resources Institute Finland, Latokartanonkaari 9, 00790, Helsinki, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Forest health is dependent on the variability of microorganisms interacting with the host tree/holobiont. Symbiotic mi- crobiota and pathogens engage in a permanent interplay, which influences the host. Thanks to the development of NGS technol- ogies, a vast amount of genetic information on the virosphere of temperate forests has been gained the last seven years. To estimate the qualitative/quantitative impact of NGS in forest virology, we have summarized viruses affecting major tree/shrub species and their fungal associates, including fungal plant pathogens, mutualists and saprotrophs. The contribution of NGS methods is ex- tremely significant for forest virology. Reviewed data about viral presence in holobionts, allowed us to address the role of the virome in the holobionts. Genetic variation is a crucial aspect in hologenome, significantly reinforced by horizontal gene transfer among all interacting actors. Through virus-virus interplays synergistic or antagonistic relations may evolve, which may drasti- cally affect the health of the holobiont. Novel insights of these interplays may allow practical applications for forest plant protec- tion based on endophytes and mycovirus biocontrol agents. -

Tree Planting and Management

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION Tree Planting and Management Breadth of Opportunity The spread of the Commission's responsibilities over some 148 countries in temperate, mediterranean, tropical and desert climates provides wonderful opportunities to experiment with nature's wealth of tree species. We are particularly fortunate in being able to grow many interesting and beautiful trees and we will explain how we manage them and what splendid specimens they can make. Why Plant Trees? Trees are planted for a variety of reasons: their amenity value, leaf shape and size, flowers, fruit, habit, form, bark, landscape value, shelter or screening, backcloth planting, shade, noise and pollution reduction, soil stabilisation and to encourage wild life. Often we plant trees solely for their amenity value. That is, the beauty of the tree itself. This can be from the leaves such as those in Robinia pseudoacacia 'Frisia', the flowers in the tropical tree Tabebuia or Albizia, the crimson stems of the sealing wax palm (Cyrtostachys renda), or the fruit as in Magnolia grandiflora. above: Sealing wax palms at Taiping War Cemetery, Malaysia with insert of the fruit of Magnolia grandiflora Selection Generally speaking the form of the left: The tropical tree Tabebuia tree is very often a major contributing factor and this, together with a sound knowledge of below: Flowers of the tropical the situation in which the tree is to tree Albizia julibrissin be grown, guides the decision to the best choice of species. Exposure is a major limitation to the free choice of species in northern Europe especially and trees such as Sorbus, Betula, Tilia, Fraxinus, Crataegus and fastigiate yews play an important role in any landscape design where the elements are seriously against a wider selection.