CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2002*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Chemistry LD

Physical Chemistry LD Electrochemistry Chemistry Electrolysis Leaflets C4.4.5.2 Determining the Faraday constant Aims of the experiment To perform an electrolysis. To understand redox reactions in practice. To work with a Hoffman electrolysis apparatus. To understand Faraday’s laws. To understand the ideal gas equation. The second law is somewhat more complex. It states that the Principles mass m of an element that is precipitated by a specific When a voltage is applied to a salt or acid solution, material amount of charge Q is proportional to the atomic mass, and is migration occurs at the electrodes. Thus, a chemical reaction inversely proportional to its valence. Stated more simply, the is forced to occur through the flow of electric current. This same amount of charge Q from different electrolytes always process is called electrolysis. precipitates the same equivalent mass Me. The equivalent mass Me is equal to the molecular mass of an element divid- Michael Faraday had already made these observations in the ed by its valence z. 1830s. He coined the terms electrolyte, electrode, anode and cathode, and formulated Faraday's laws in 1834. These count M M = as some of the foundational laws of electrochemistry and e z describe the relationships between material conversions In order to precipitate this equivalent mass, 96,500 Cou- during electrochemical reactions and electrical charge. The lombs/mole are always needed. This number is the Faraday first of Faraday’s laws states that the amount of moles n, that constant, which is a natural constant based on this invariabil- are precipitated at an electrode is proportional to the charge ity. -

The Laby Experiment

Anna Binnie The Laby Experiment Abstract After J.J. Thomson demonstrated that the atom was not an indivisible entity but contained negatively charged corpuscles, the search for the determination of magnitude of this fundamental unit of electric charge commenced. This paper will briefly discuss the different attempts to measure this quantity of unit charge e. It will outline the progress of these attempts and will focus on the little known work of Australian, Thomas Laby, who attempted to reconcile the value of e determined from two very different approaches. This was probably the last attempt to measure e and was made at a time that most of the scientific world was busy with other issues. The measurement of the unit electric charge e, by timing the fall of charged oil drops is an experiment that has been performed by generations of undergraduate physics students. The experiment is often termed the Millikan oil drop experiment after R.A. Millikan (1868-1953) who conceived and performed it during the period 1907-1917. This experiment was repeated in 1939-40 by V.D. Hopper (1913b), lecturer in Natural Philosophy at Melbourne University and T.H. Laby (1880-1946) who was Professor. As far as we know this was the last time that the experiment was performed “seriously”, i.e. performed carefully by professional physicists and fully reported in major journals. The question arises who was Laby and why did he conduct this experiment such along time after Millikan has completed his work? Thomas Laby was born in 1880 at Creswick Victoria. In 1883 the family moved to New South Wales where young Thomas was educated. -

New Best Estimates of the Values of the Fundamental Constants

ing a vicious cycle in of the base units of our system of measurement, such which developing as the kilogram, metre, second, ampere, and kelvin— countries that lag in the base units of the SI, the International System of S&T capacity fall fur- units. The Consultative Committee for Units (of the ther behind, as International Committee on Weights and Measures, industrialized BIPM/CCU) advises the Comité International des nations with financial Poids et Mesures on defining (or redefining) each of resources and a the base units of the SI in terms of the fundamental trained scientific constants rather than in terms of material artefacts or work force exploit time intervals related to the rotation of the earth. new knowledge and Today, some, but not all, of the base units of the SI are technologies more defined in this way, and we are working on the quickly and inten- remainder. sively. These deficits can leave entire developing In December 2003, new best estimates of the fun- economies behind. And when nations need to damental constants were released. These are com- respond to diseases such as HIV or SARS, or make piled and published with the authority of a CODATA decisions about issues such as stem-cell research or committee that exists for this purpose, but in practice genetically modified foods, this lack of S&T infrastruc- they are produced (on this occasion) by Barry Taylor ture can breed unfounded fear and social discord. and Peter Mohr at the U.S. National Institute for The report asserts that there is no reason why, in an Standards and Technology (NIST), in Gaithersburg, era in which air travel and the Internet already tightly MD. -

Experiment 21A FARADAY's

Experiment 21A FV 11/15/11 FARADAY’S LAW MATERIALS: DPDT (double pole/double throw) switch, digital ammeter, J-shaped platinum electrode and holder, power supply, carbon electrode, electrical lead, 10 mL graduated cylinder, 100 mL beaker, 400 mL beaker, buret, thermometer, starch solution, 0.20 M KI, 1 M H2SO4, 0.0200 M Na2S2O3. PURPOSE: The purpose of this experiment is to determine values for the Faraday constant and Avogadro’s number. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: By the end of this experiment, the student should be able to demonstrate the following proficiencies: 1. Construct an electrolytic cell from a diagram. 2. Determine the number of moles of products formed in a redox reaction from experimental data. 3. Determine the total charge that has passed through an electrolytic cell. 4. Calculate values for the Faraday constant and Avogadro’s number from experimental data. DISCUSSION: Forcing an electrical current through an electrolytic cell can cause a nonspontaneous chemical reaction to occur. For example, when direct current is passed through a solution of aqueous potassium iodide, KI, the following reactions occur at the electrodes: − − anode: 2 I (aq) → I2 (aq) + 2 e (oxidation) − − cathode: 2 H2O (l) + 2 e → H2 (g) + 2 OH (aq) (reduction) − − overall redox: 2 I (aq) + 2 H2O (l) → I2 (aq) + H2 (g) + 2 OH (aq) Electrons can be treated stoichiometrically like the other chemical species in these reactions. Thus, the number of moles of products formed is related to the number of moles of electrons that pass through the cell during the electrolysis. Iodine is formed at the anode in this electrolysis and dissolves in the solution upon stirring.1 Hydrogen gas is formed at the cathode and will be collected in an inverted graduated cylinder by displacement of water. -

Problem-Solving Tactics

17.26 | Electrochemistry PROBLEM-SOLVING TACTICS (a) Related to electrolysis: Electrolysis comprises of passing an electric current through either a molten salt or an ionic solution. Thus the ions are “forced” to undergo either oxidation (at the anode) or reduction (at the cathode). Most electrolysis problems are really stoichiometry problems with the addition of some amount of electric current. The quantities of substances produced or consumed by the electrolysis process is dependent upon the following: (i) Electric current measured in amperes or amps (ii) Time measured in seconds (iii) The number of electrons required to produce or consume 1 mole of the substance (b) To calculate amps, time, coulombs, faradays and moles of electrons: Three equations related these quantities: (i) Amperes × time = Coulombs (ii) 96,485 coulombs = 1 Faraday (iii) 1 Faraday = 1 mole of electrons The through process for interconverting amperes and moles of electrons is: Amps and time Coulombs Faradays Moles of electrons Use of these equations are illustrated in the following sections. (c) To calculate the quantity of substance produced or consumed: To determine the quantity of substance either produced or consumed during electrolysis, given the time a known current flowed: (i) Write the balanced half-reactions involved. (ii) Calculate the number of moles of electrons that were transferred. (iii) Calculate the number of moles of substance that was produced/consumed at the electrode. (iv) Convert the moles of substance to desired units of measure. (d) Determination of standard cell potentials: A cell’s standard state potential is the potential of the cell under standard state conditions, and it is approximated with concentrations of 1 mole per liter (1 M) and pressures of 1 atmosphere at 25ºC. -

P3.2.5.1 Conducting Electricity by Means of Electrolysis

LD Electricity Physics Fundamentals of electricity Leaflets P3.2.5.1 Conducting electricity by means of electrolysis Determining the Faraday constant Objects of the experiments Producing hydrogen by means of electrolysis and measuring the volume V of the hydrogen. Measuring the electrical work W required at a fixed voltage U0. Calculating the Faraday constant F. Principles In electrolysis, current flow is accompanied by chemical Inserting the number of moles n for the quantity of substance deposition. The quantity of substance deposited is propor- deposited and taking into account the valence z of the ions tional to the charge Q which has flowed through the electrolyte. deposited, one obtains the relation that determines the charge The charge transported can be calculated with the help of the transported: Faraday constant F. This universal constant is related to the Q = n ⋅ F ⋅ z (II). elementary charge e via the Avogadro number NA: F = N ⋅ e (I). In this experiment, the Faraday constant is determined by A producing a certain quantity of hydrogen by means of elec- This means, the Faraday constant F is the charge quantity of trolysis. The hydrogen gas formed in the electrolysis is col- 1 mole of electrons. lected at an external pressure p and a room temperature T. Then its volume V is measured. The number of moles n1 of hydrogen molecules produced is calculated with the ideal gas equation: pV n = (III) 1 RT J with R = 8.314 (general gas constant) mole ⋅ K Each H+ ion is neutralized by an electron from the electrolytic current, that is, the valence z of hydrogen ions is equal to 1. -

State Standard of Electrical Resistance on the Basis of Von Klitzing Constant

URN (Paper): urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2014iwk-149:8 58th ILMENAU SCIENTIFIC COLLOQUIUM Technische Universität Ilmenau, 08 – 12 September 2014 URN: urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2014iwk:3 STATE STANDARD OF ELECTRICAL RESISTANCE ON THE BASIS OF VON KLITZING CONSTANT Bohdan Stadnyk, Svyatoslav Yatsyshyn Lviv Polytechnic National University, Information-measuring technology department, 12, Bandera Street, 79013, Lviv, Ukraine Phone/Fax: (+380) 32-258-23-15 ABSTRACT In this work we discuss the development problem of the high-precision reference standards. We propose to develop the state Ukrainian standard of electrical resistance based on a permanence of an inverse of conductance quantum or von Klitzing constant. Its numerical value is determined by two physical constants of substance. Therefore there exist some discussed and solved problems of numerical value of aforementioned quantity implementation to the performance of current state standard of electric resistance. Index Terms – State standard of electrical resistance, von Klitzing constant, Hamon network. 1. INTRODUCTION In this work we discuss the problem of implementation of the high-precision reference standards just as it was regarded by participants of Royal Society Discussion Meeting, for instance by [1]. We consider the state standard of electrical resistance. This standard is proposed to develop by applying the latest nanotechnology achievements, such as research of electrical conductivity of carbon nanotubes. 2. STATE OF PROBLEM According to the state primary standard unit of electrical resistance, physical value or range of values of a physical quantity that is realized by standard is equal to 1 ohm and 100 ohms. State primary standard provides storage, verification and supervision of the mentioned unit -8 with standard deviation measurement result Sm not exceeding 3·10 ohm at 10 independent observations. -

Combinatorial Synthesis and High-Throughput Characterization of Multinary Vanadate Thin-Film Materials Libraries for Solar Water Splitting’ Supervisors: Prof

Combinatorial Synthesis and High- Throughput Characterization of Multinary Vanadate Thin-Film Materials Libraries for Solar Water Splitting Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor-Ingenieurin der Fakultät für Maschinenbau der Ruhr-Universität Bochum von Swati Kumari aus Begusarai, India Bochum 2020 The presented work was carried out from August 2016 to April 2020 at the chair of Materials Discovery and Interfaces (MDI) under the supervision of Prof. Dr.-Ing. Alfred Ludwig in the Institute for Materials, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany. Dissertation eingereicht am: 21.04.2020 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 27.05.2020 Vorsitz: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Andreas Kilzer Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Alfred Ludwig Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Wolfgang Schuhmann “Child-like curiosity – seeking, questioning, and understanding – is the basis of knowledge that opens up new avenues that we call progress.” – Klaus von Klitzing – Abstract Solar water splitting using a photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) is an attractive route for the generation of clean and renewable fuels. PEC cell converts solar energy into an intermediate chemical energy carrier such as molecular hydrogen and oxygen. The solar-driven oxygen evolution at photoanode is limited due to the lack of materials with suitable optical, electronic properties, and operational stability. In this thesis, combinatorial synthesis and high- throughput characterization methods were used to investigate the suitability of multinary vanadium-based material systems for PEC application. Multinary ternary (M-V-O) and quaternary (M1-M2-V-O) metal vanadium oxide photoanodes: Fe-V-O, Cu-V-O, Ag-V-O, W-V-O, Cr-V-O, Co-V-O, Cu-Fe-V-O, and Ti-Fe-V-O materials libraries were synthesized using combinatorial reactive magnetron sputtering with a continuous composition and thickness gradients. -

Quantitative Electrochemistry

Quantitative Electrochemistry Introduction SCIENTIFIC What is the relationship between the quantity of electricity and the extent of a chemical reaction in an electrochemical process? Concepts • Electrolysis • Current (amperes) • Electrical charge (coulombs) • Faraday constant (coulombs per mole) Background The principles governing the amount of product obtained in electrolysis were developed by Michael Faraday in his 1834 paper entitled “On Electrical Decomposition.” The terms he defined are still used today to describe electrochemical cells (electrode, cathode, anode, electrolyte, etc.). Michael Faraday also laid out the mathematical relationship between the quantity of electricity and the amount of a substance produced in electrolysis. • The amount of a substance deposited on each electrode in an electrolytic cell is directly proportional to the quantity of elec- tricity passed through the cell. • The quantity of an element deposited by a given amount of electricity depends on its chemical equivalent weight. Faraday’s work in electrochemistry has been honored in the name of the Faraday constant, a fundamental physical constant corresponding to the charge in coulombs of one mole of electrons. In this experiment, the value of the Faraday constant will be determined by measuring the amount of copper obtained in an electroplating reaction. Electroplating is the process of depositing a metal on the surface of a conductor by passing electricity through a solution of metal ions. Figure 1 shows a basic diagram of an electrolytic cell for a “copper-plating” reaction. The electrodes are copper metal. Oxidation of copper metal to copper(II) ions occurs at the anode, and reduction of copper(II) ions to copper metal occurs at the cathode. -

Electrical Engineering Units and Constants

268" U.S. Department of Commerce NBS Misc. Publ. National Bureau of Standards Issued June 1%5 Washington, D.C. 20234 Price 10?; S6.2o per 100 ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING UNITS AND CONSTANTS As adopted by NBS 1 Symbols and Units Quantity Symbol Unit Symbol charge Q coulomb current I ampere voltage, potential v volt difference electromotive force e resistance R onm 0 mh<i conductance c mhu A/V, ( (Siemens) (Si reactance x ohm n susceptance B mhu A/V, or mho impedance z ohm n admittance ) mho A/V, or mho capacitance c farad F inductance L henry H energy, work w joule J power p watt w resistivity p ohm -meter Dm conductivity mho per meter mho/ in electric displacement D coulomb per sq C/'nr meter Y/m electric field strength E volt per meter permittivity labsolute € farad per meter F/m relative permittivity € r (numeric! magnetic flux <t> weber Wh magnetomotive force ampere (ampere A turn* reluctance •ft ampere per A/W b weber permeance & weber per Wb/A ampere |uverl Reprinted from NBS Technical New* Bulletin. May 1965. •For sale bv the Superintendent of D> nts. I S. Government Printing Office. Washington. D.C. 20402 nre 10<: S6.2.S per 100 ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING UNITS AND CONSTANTS Symbols and Units — Continued Quantity Symbol Unit Si m bol magnetic flux density B tesla T magnetic field strength 11 ampere per A/m meter permeability (absolute) henry per meter H/m relative permeability (numeric! length / meter m mass m kilogram kg time t second s frequency f hertz Hz angular frequency- radian per rad/s second force F newton N pressure P newton per sq. -

Physical Units, Constants and Conversion Factors

Physical Units, Constants and Conversion Factors Here we regroup the values of the most useful physical and chemical constants used in the book. Also some practical combinations of such constants are provided. Units are expressed in the International System (SI), and conversion to the older CGS system is also given. For most quantities and units, the practical definitions currently used in the context of biophysics are also shown. © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 609 F. Cleri, The Physics of Living Systems, Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-30647-6 610 Physical units, constants and conversion factors Basic physical units (boldface indicates SI fundamental units) SI cgs Biophysics Length (L) meter (m) centimeter (cm) Angstrom (Å) 1 0.01 m 10−10 m Time (T) second (s) second (s) 1 µs=10−6 s 1 1 1ps=10−12 s Mass (M) kilogram (kg) gram (g) Dalton (Da) −27 1 0.001 kg 1/NAv = 1.66 · 10 kg Frequency (T−1) s−1 Hz 1 1 Velocity (L/T) m/s cm/s µm/s 1 0.01 m/s 10−6 m/s Acceleration (L/T2) m/s2 cm/s2 µm/s2 1 0.01 m/s2 10−6 m/s2 Force (ML/T2) newton (N) dyne (dy) pN 1kg· m/s2 10−5 N 10−12 N Energy, work, heat joule (J) erg kB T (at T = 300 K) (ML2/T2) 1kg· m2/s2 10−7 J 4.114 pN · nm 0.239 cal 0.239 · 10−7 cal 25.7 meV 1C· 1V 1 mol ATP = 30.5 kJ = 7.3 kcal/mol Power (ML2/T3) watt (W) erg/s ATP/s 1kg· m2/s3 =1J/s 10−7 J/s 0.316 eV/s Pressure (M/LT2) pascal (Pa) atm Blood osmolarity 1 N/m2 101325˙ Pa ∼ 300 mmol/kg 1 bar = 105 Pa ∼300 Pa = 3 · 10−3 atm Electric current (A) ampere (A) e.s.u. -

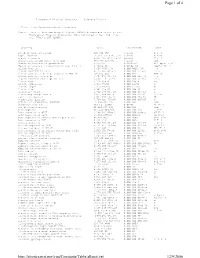

Physical Constants --- Complete Listing

Page 1 of 4 Fundamental Physical Constants --- Complete Listing From: http://physics.nist.gov/constants Source: Peter J. Mohr and Barry N. Taylor, CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2002, published in Rev. Mod. Phys. vol. 77(1) 1-107 (2005). Quantity Value Uncertainty Unit ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ speed of light in vacuum 299 792 458 (exact) m s^-1 magn. constant 12.566 370 614...e-7 (exact) N A^-2 electric constant 8.854 187 817...e-12 (exact) F m^-1 characteristic impedance of vacuum 376.730 313 461... (exact) ohm Newtonian constant of gravitation 6.6742e-11 0.0010e-11 m^3 kg^-1 s^-2 Newtonian constant of gravitation over h-bar c 6.7087e-39 0.0010e-39 (GeV/c^2)^-2 Planck constant 6.626 0693e-34 0.000 0011e-34 J s Planck constant in eV s 4.135 667 43e-15 0.000 000 35e-15 eV s Planck constant over 2 pi times c in MeV fm 197.326 968 0.000 017 MeV fm Planck constant over 2 pi 1.054 571 68e-34 0.000 000 18e-34 J s Planck constant over 2 pi in eV s 6.582 119 15e-16 0.000 000 56e-16 eV s Planck mass 2.176 45e-8 0.000 16e-8 kg Planck temperature 1.416 79e32 0.000 11e32 K Planck length 1.616 24e-35 0.000 12e-35 m Planck time 5.391 21e-44 0.000 40e-44 s elementary charge 1.602 176 53e-19 0.000 000 14e-19 C elementary charge over h 2.417 989 40e14 0.000 000 21e14 A J^-1 magn.