Translating Non-Standard Language: Andrea Camilleri in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download a Reference Grammar of Modern Italian

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF MODERN ITALIAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Maiden,Cecilia Robustelli | 512 pages | 01 Jun 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780340913390 | Italian | London, United Kingdom A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian PDF Book This Italian reference grammar provides a comprehensive, accessible and jargon-free guide to the forms and structures of Italian. This rule is not absolute, and some exceptions do exist. Parli inglese? Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia , as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has many inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e. An instance of neuter gender also exists in pronouns of the third person singular. Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Retrieved 7 August Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. For a group composed of boys and girls, ragazzi is the plural, suggesting that -i is a general plural. Book is in Used-Good condition. Story of Language. A history of Western society. It formerly had official status in Albania , Malta , Monaco , Montenegro Kotor , Greece Ionian Islands and Dodecanese and is generally understood in Corsica due to its close relation with the Tuscan-influenced local language and Savoie. -

When Latin Gets Sick: Mocking Medical Language in Macaronic Poetry

JAHR Vol. 4 No. 7 2013 Original scientific article Šime Demo* When Latin gets sick: mocking medical language in macaronic poetry ABSTRACT Macaronic poetry is a curious cultural phenomenon, having originated in classical antiquity and taken its standard form in the 15th century in northern Italy. Its basic feature is mixing of linguistic varieties for a humorous effect. In this paper, connections between macaronic poetry and the language of medicine have been observed at three levels. Firstly, starting with the idea of language as a living organism, in particular Latin (Renaissance language par excellence), its illness, from a humanist point of view, brought about by uncontrolled contamination with vernacular, serves as a stimulus for its parodying in macaronic poetry; this is carried out by sys- tematically joining together stable, "healthy", classical material with inconsistent, "contagious" elements of the vernacular. Secondly, a macaronic satire of quackery, Bartolotti’s Macharonea medicinalis, one of the earliest macaronic poems, is analysed. Finally, linguistic expressions of anatomical and pathological matter in macaronic poetry are presented in some detail, as in, for example, the provision of a disproportionately high degree of scatological and obscene content in macaronic texts, as well as a copious supply of lively metaphors concerning the body, and parodical references to medical language that abound. Furthermore, anatomical representations and descriptions of pathological and pseudo-pathological conditions and medical procedures are reviewed as useful as displays of cultural matrices that are mirrored in language. Linguistic mixing, be it intentional or inadvertent, exists wherever linguistically distinct groups come into contact.1 As a rule, linguistic varieties do not have the same social value because the groups that use them are socially different. -

Crime Fiction

└ Index CRIME FICTION Please note that a fund for the promotion of Icelandic literature operates under the auspices of the Icelandic Ministry Forlagid of Education and Culture and subsidizes translations of literature. Rights For further information please write to: Icelandic Literature Center Hverfisgata 54 | 101 Reykjavik Agency Iceland Phone +354 552 8500 [email protected] | www.islit.is crime fiction · 1 · CRIME FICTION crime fiction UA MATTHIASDOTTIR [email protected] VALGERDUR BENEDIKTSDOTTIR [email protected] · 3 · CRIME FICTION crime Arnaldur Indridason Arni Thorarinsson fiction Oskar Hrafn Thorvaldsson Ottar M. Nordfjord Solveig Palsdottir Stella Blomkvist Viktor A. Ingolfsson rights-agency · 3 · └ Index CRIME FICTION ARNALDUR INDRIDASON (b.1961) has the rare distinction of having won the Nordic Crime Novel Prize two years running. He is also the winner of the highly respected and world famous CWA Gold Dagger Award for the top crime novel of the year in the English language, Silence of the Grave. Indridason’s novels have sold over ten million copies worldwide, in 40 languages. Oblivion Kamp Knox, crime novel, 2014 On the Reykjanes peninsula in 1979, a body is “One of the most compelling found floating in a lagoon created by a geother- detectives anyone has mal power station. The deceased seems to be linked with the nearby American military base, written anywhere.” but authorities there have little interest in work- CRIME TIME, UK ing with the Icelandic police. While Erlendur and Marion Briem pursue their leads, Erlendur has his mind on something else as well: a young girl Sold to: who disappeared without a trace around one of UK/Australia/New Zealand/South Africa (Random House/Harvill Secker); USA/Philippines Reykjavik’s most notorious neighbourhoods, a (St. -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

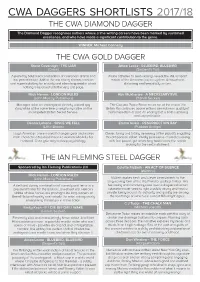

Cwa Daggers Shortlists 2017/18

CWA DAGGERS SHORTLISTS 2017/18 THE CWA DIAMOND DAGGER The Diamond Dagger recognises authors whose crime writing careers have been marked by sustained excellence, and who have made a significant contribution to the genre. WINNER: Michael Connelly THE CWA GOLD DAGGER Steve Cavanagh - THE LIAR Attica Locke - BLUEBIRD, BLUEBIRD (Orion) (Serpent's Tail) A perfectly balanced combination of courtroom drama and Police attitudes to Texas killings reveal the still rampant fast-paced action. Add to the mix strong characterisation racism of the American justice system. Atmospheric, and superb plotting for a twisty and absorbing read in which disturbing and beautifully written. nothing is resolved until the very last page. Mick Herron - LONDON RULES Abir Mukherjee - A NECESSARY EVIL (John Murray Publishers) (Harvill Secker) Manages to be an exciting and cleverly plotted spy The Calcutta Police Force series set at the end of the story while at the same time a very funny satire on the British Raj continues apace with no diminution in quality of incompetent British Secret Service. characterisation or plot. An ending that is both surprising and unpredictable. Dennis Lehane - SINCE WE FELL Emma Viskic - RESURRECTION BAY (Little Brown) (Pushkin Vertigo) Tough American crime novelist changes gear and makes Clever, funny and totally deserving of the plaudits engulfing main character a troubled insecure woman who kills her this antipodean début. Vividly persuasive characters along husband. Guns give way to deep psychology. with fast-paced, gut-wrenching twists leave the reader craving for the next instalment. THE IAN FLEMING STEEL DAGGER Sponsored by Ian Fleming Publications Ltd. Colette McBeth - AN ACT OF SILENCE (Wildfire) Mick Herron - LONDON RULES (John Murray Publishers) McBeth makes fresh and clever amendments to the long-serving form of the Westminster political thriller. -

Intrinsic Motivation

Reading and the Native American Learner Research Report Dr. Terry Bergeson State Superintendent of Public Instruction Andrew Griffin, Ed.D. Director Higher Education, Community Outreach, and Staff Development Denny Hurtado, Program Supervisor Indian Education/Title I Program This material available in alternative format upon request. Contact Curriculum and Assessment, 360/753-3449, TTY 360/664-3631. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction complies with all federal and state rules and regulations and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, age, or marital status. June 2000 ii This report was prepared by: Joe St. Charles, M.P.A. Magda Costantino, Ph.D. The Evergreen Center for Educational Improvement The Evergreen State College In collaboration with the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Office of Indian Education With special thanks to the following reviewers: Diane Brewer Sally Brownfield William Demmert Roy DeBoer R. Joseph Hoptowit Mike Jetty Acknowledgement to Lynne Adair for her assistance with the project. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................3 THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION ................................................................... 9 SOURCES OF EDUCATIONAL DIFFICULTIES -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

The Role of Italy in Milton's Early Poetic Development

Italia Conquistata: The Role of Italy in Milton’s Early Poetic Development Submitted by Paul Slade to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in December 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract My thesis explores the way in which the Italian language and literary culture contributed to John Milton’s early development as a poet (over the period up to 1639 and the composition of Epitaphium Damonis). I begin by investigating the nature of the cultural relationship between England and Italy in the late medieval and early modern periods. I then examine how Milton’s own engagement with the Italian language and its literature evolved in the context of his family background, his personal contacts with the London Italian community and modern language teaching in the early seventeenth century as he grew to become a ‘multilingual’ poet. My study then turns to his first published collection of verse, Poems 1645. Here, I reconsider the Italian elements in Milton’s early poetry, beginning with the six poems he wrote in Italian, identifying their place and significance in the overall structure of the volume, and their status and place within the Italian Petrarchan verse tradition. -

Two Introductory Texts on Using Statistics for Linguistic Research and Two Books Focused on Theory

1. General The four books discussed in this section can be broadly divided into two groups: two introductory texts on using statistics for linguistic research and two books focused on theory. Both Statistics for Linguists: A Step-by-Step Guide for Novices by David Eddington and How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis by Natalia Levshina offer an introduction to statistics and, more specifically, how it can be applied to linguistic research. Covering the same basic statistical concepts and tests and including hands- on exercises with answer keys, the textbooks differ primarily in two respects: the choice of statistical software package (with subsequent differences reflecting this choice) and the scope of statistical tests and methods that each covers. Whereas Eddington’s text is based on widely used but costly SPSS and focuses on the most common statistical tests, Levshina’s text makes use of open-source software R and includes additional methods, such as Semantic Vector Spaces and making maps, which are not yet mainstream. In his introduction to Statistics for Linguists, Eddington explains choosing SPSS over R because of its graphical user interface, though he acknowledges that ‘in comparison to SPSS, R is more powerful, produces better graphics, and is free’ (p. xvi). This text is therefore more appropriate for researchers and students who are more comfortable with point-and-click computer programs and/or do not have time to learn to manoeuvre the command-line interface of R. Eddington’s book also has the goal of being ‘a truly basic introduction – not just in title, but in essence’ (p. -

MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, and LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

BILINGUAL NAVAJO: MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, AND LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte C. Schaengold, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Brian Joseph, Advisor Professor Donald Winford ________________________ Professor Keith Johnson Advisor Linguistics Graduate Program ABSTRACT Many American Indian Languages today are spoken by fewer than one hundred people, yet Navajo is still spoken by over 100,000 people and has maintained regional as well as formal and informal dialects. However, the language is changing. While the Navajo population is gradually shifting from Navajo toward English, the “tip” in the shift has not yet occurred, and enormous efforts are being made in Navajoland to slow the language’s decline. One symptom in this process of shift is the fact that many young people on the Reservation now speak a non-standard variety of Navajo called “Bilingual Navajo.” This non-standard variety of Navajo is the linguistic result of the contact between speakers of English and speakers of Navajo. Similar to Michif, as described by Bakker and Papen (1988, 1994, 1997) and Media Lengua, as described by Muysken (1994, 1997, 2000), Bilingual Navajo has the structure of an American Indian language with parts of its lexicon from a European language. “Bilingual mixed languages” are defined by Winford (2003) as languages created in a bilingual speech community with the grammar of one language and the lexicon of another. My intention is to place Bilingual Navajo into the historical and theoretical framework of the bilingual mixed language, and to explain how ii this language can be used in the Navajo speech community to help maintain the Navajo language. -

Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate

Zohar Shavit “Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate ABSTRACT “Hebraization” was a project of nation building—the building of a new Hebrew nation. Intended to forge a population comprising numerous lan- guages and cultural affinities into a unified Hebrew-speaking society that would actively participate in and contribute creatively to a new Hebrew- language culture, it became an integral and vital part of the Zionist narrative of the period. To what extent, however, did the ideal mesh with reality? The article grapples with the unreliability of official assessments of Hebrew’s dominance, and identifies and examines a broad variety of less politicized sources, such as various regulatory, personal, and commercial documents of the period as well as recently-conducted oral interviews. Together, these reveal a more complete—and more complex—portrait of the linguistic reality of the time. INTRODUCTION The project of making Hebrew the language of the Jewish community in Eretz-Israel was a heroic undertaking, and for a number of reasons. Similarly to other groups of immigrants, the Jewish immigrants (olim) who came to Eretz-Israel were required to substitute a new language for mother tongues in which they were already fluent. Unlike other groups Israel Studies 22.1 • doi 10.2979/israelstudies.22.1.05 101 102 • israel studies, volume 22 number 1 of immigrants, however, they were also required to function in a language not yet fully equipped to respond to all their needs for written, let alone spoken, communication in the modern world. -

Adjectives That Start with M: a List of 790+ Words with Examples

PDF Version In English, over 790 adjectives start with the letter M. Use these words in your speech and writing to express exactly what you see and feel and to boost your vocabulary! Table Of Contents: Adjectives That Start with MA (201 Words) Adjectives That Start with ME (162 Words) Adjectives That Start with MI (132 Words) Adjectives That Start with MO (183 Words) Adjectives That Start with MU (88 Words) Adjectives That Start with MY (24 Words) Other Lists of Adjectives Adjectives That Start with MA (201 Words) Shockingly repellent; inspiring horror The mood set by the music macabre appeals to many who enjoy the strange and macabre. Of or containing a mixture of latin words and vernacular words macaronic jumbled together How is a patois compared or contrasted to the concept of a macaronic language Of or relating to macedonia or its inhabitants Work on the macedonian macedonian standard language. macerative Accompanied by or characterized by maceration Of or relating to machiavelli or the principles of conduct he machiavellian recommended Coercive power is machiavellian in nature and is the opposite of reward power. machinelike Resembling the unthinking functioning of a machine Used of men; markedly masculine in appearance or manner macho Contrast the male characters with the often macho male leads of shonen comics. GrammarTOP.com macrencephalic Having a large brain case macrencephalous Having a large brain case Very large in scale or scope or capability Rather, it was addressing macro the macro issue. Of or relating to the theory or practice of macrobiotics Foods such macrobiotic as these are used in a macrobiotic way of eating.