Spike Lee's She's Gotta Have It (1986), up by a Distributor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Daly, Timothy Michael (2016) Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books. Doctoral thesis (PhD), Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/617237/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly PhD 2016 Towards a fugitive press: materiality and the printed photograph in artists’ books Tim Daly A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy MIRIAD Manchester Metropolitan University June 2016 Contents a. Abstract 1 b. Research question 3 c. Field 5 d. Aims and objectives 31 e. Literature review 33 f. Methodology 93 g. Practice 101 h. Further research 207 i. Contribution to knowledge 217 j. Conclusion 220 k. Index of practice conclusions 225 l. References 229 m. Bibliography 244 n. Research outputs 247 o. Appendix - published research 249 Tim Daly Speke (1987) Silver-gelatin prints in folio A. Abstract The aim of my research is to demonstrate how a practice of hand made books based on the materiality of the photographic print and photo-reprography, could engage with notions of touch in the digital age. We take for granted that most artists’ books are made from paper using lithography and bound in the codex form, yet this technology has served neither producer nor reader well. As Hayles (2002:22) observed: We are not generally accustomed to thinking about the book as a material metaphor, but in fact it is an artifact whose physical properties and historical usage structure our interactions with it in ways obvious and subtle. -

ADKINS-DOCUMENT-2016.Pdf

Copyright Alexander Adkins 2016 ABSTRACT Postcolonial Satire in Cynical Times by Alexander Adkins Following post-1945 decolonization, many anticolonial figures became disenchanted, for they witnessed not the birth of social revolution, but the mere transfer of power from corrupt white elites to corrupt native elites. Soon after, many postcolonial writers jettisoned the political sincerity of social realism for satire—a less naïve, more pessimistic literary genre and approach to social critique. Satires about the postcolonial condition employ a cynical idiom even as they often take political cynicism as their chief object of derision. This dissertation is among the first literary studies to discuss the use of satire in postcolonial writing, exploring how and why some major Anglophone global writers from decolonization onward use the genre to critique political cynicisms affecting the developing world. It does so by weaving together seemingly disparate novels from the 1960s until today, including Chinua Achebe’s sendup of failed idealism in Africa, Salman Rushdie’s and Hanif Kureishi’s caricatures of Margaret Thatcher’s enterprise culture, and Aravind Adiga’s and Mohsin Hamid’s parodies of self-help narratives in South Asia. Satire is an effective form of social critique for these authors because it is equal opportunity, avoiding simplistic approaches to power and oppression in the postcolonial era. Satire often blames everyone—including itself—by insisting on irony, hypocrisy, and interdependence as existential conditions. Postcolonial satires ridicule victims and victimizers alike, exchanging the politics of blame for messiness, association, and implication. The satires examined here emphasize that we are all, to different degrees, mutually implicated subjects, especially in the era of global capitalism. -

Sweet Honey in the Rock Been Unprovoked by the 30 Pieces of Silver

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS ABOUT THE ARTISTS Sunday, May 6, 2012, 7pm “I have always believed that art is the conscience each other, our fellow creatures who share this Zellerbach Hall of the human soul, and that artists have the planet, and the planet itself. responsibility not only to show life as it is but Sweet Honey’s 20th CD release, to show life as it should be. … Sweet Honey In Experience…101, was a 2008 Grammy Award The Rock has withstood the onslaught. She has nominee. The excitement continued as Sweet Sweet Honey In The Rock been unprovoked by the 30 pieces of silver. Her Honey was asked to compose new material songs lead us to the well of truth that nourishes in celebration of Alvin Ailey Dance Theater’s the will and courage to stand strong. She is the 50th anniversary. Together, these two artistic keeper of the flame.” treasures of the African American experience Harry Belafonte performed this once-in-a-lifetime collaboration throughout the United States. The music for the collaboration was released on a CD entitled Go ounded by bernice johnson reagon in Grace. Fin 1973 (with Mie, Carol Maillard and On February 18, 2009, Sweet Honey gave a Louise Robinson) at the D.C. Black Repertory concert at the White House at the invitation of Theater Company, Sweet Honey In The Rock, President and Mrs. Barack Obama. the internationally renowned a cappella ensem- The following year saw the release of a CD and ble, has been a vital and innovative presence in video in response to Arizona Law SB-1070, and the music culture of Washington, D.C., and in the creation of a tribute concert, “Remembering communities of conscience around the world. -

The Nothing Hanif Kureishi

JUNE 2018 Into the Night Sarah Bailey The riveting follow-up to The Dark Lake, acclaimed debut novel and international bestseller. Description 'The Dark Lake is a stunning debut that gripped me from page one and never eased up. Dark, dark, dark--but infused with insight, pathos, a great sense of place, and razor-sharp writing. It's going to be big and Sarah Bailey needs to clear a shelf for awards.' C. J. Box, #1 New York Times bestselling author Sarah Bailey's acclaimed debut novel The Dark Lake was a bestseller around the world and Bailey's taut and suspenseful storytelling earned her fitting comparisons with Gillian Flynn and Paula Hawkins. Into the Night is her stunning new crime novel featuring the troubled and brilliant Detective Sergeant Gemma Woodstock. This time Gemma finds herself lost and alone in the city, broken-hearted by the decisions she's had to make. Her new workplace is a minefield and the partner she has been assigned is uncommunicative and often hostile. When a homeless man is murdered and Gemma is put on the case, she can't help feeling a connection with the victim and the lonely and isolated life he led despite being in the middle of a bustling city. Then a movie star is killed in bizarre circumstances on the set of a major in the middle of aon the set of a major film shoot, and Gemma and her partner Detective Sergeant Nick Fleet have to put aside their differences to unravel the mysteries surrounding the actor's life and death. -

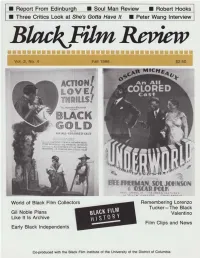

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

S^Sts4r Jissti^^U E

AMERICAN LEGION NEWS SERVICE NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS |_^ WASHINGTON HEADQUARTERS P.O. Box 1055 1608 K St., N.W. Indianapolis, Indiana 46206 Washington, D.C. 20006 MEIrose 5-8411 Executive 3-4814 JAMES C. WATKINS, Director ROD ANDERSON, Asst. Director FRANK X. KELLY, Asst. Director C. D. "Peke" DeLOACH, Chairman Washington, D.C. Indianapolis, Indiana Washington, DC. Washington, D.C. [repared And Distributed By THE AMERICAN LEGION National Public Relations Division AMERICAN LEGION NEWS BRIEFS FOR WEEK ENDING 12-2-66 THe American Legion has passed th«jhJUT-W marK in ItjWW ■^S."SSTS. ments also surpassed their nationally-assigned target for the date. * * * I The American Legion Department of Hawaii ^"JL"*1" f gf ^^^t^lne. centage tasis '--—*4 of £■£ « ^0^!^^ £^L S« to thein s^stscomparison with rthe jissti^^usame date last year. E-Hawaii -i^r^aTeaisrsLSVers: talked up a healtnyx<+ P with 2,^8 members transmitted by Nov. 18, as compared with 1,697 last year, * * * ~ „ v TV. nf vi Tinrado Ark., a leader in The American Legion ana its^Sriilf Serf ^tiJiSerS^ £.** or indies .stained in an automobile accident ten days earlier. * * * 4- „* mhp /imprican Lesion have reached their quotas in the sale of e f h ■»,. JrSan SBrntor y," oyTaJmon4 X. Jr. They are Maeama, California, Panama and Utah. * * * I JacK Williams, veteran adjutant of The American Legion Department of Nortb^ota, St T^IoTt D. nf^IranierTtS^from ^ind^oiifvA Hospital hy air amnulance Nov. 21. * * * Oscar Hrovn, the 1963 »inner of ^^.J^^^SJ^^Jit^i^ In SS^^SraSiT^r^^^cfS: Atlanta Bra^ farm team at va*ima, Wash., (Northwest League) this past season. -

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

Congratulations to Marla Gibbs for Her Star Unveiled Later Today on The

Congratulations to Marla Gibbs for Her Star Unveiled Later Today on the Hollywood Walk of Fame But Hollywood Chamber Continues to "Pass Over" the Installation of the Star Awarded to "Thanks for the Memory" Lyricist 31 Years Ago Yet Never Installed SHERMAN OAKS, CA / ACCESSWIRE / July 20, 2021 / Leo Robin Music congratulates actress Marla Gibbs, who will have her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame unveiled at a ceremony later this morning. She is probably best known for her role as the sassy maid Florence Johnston on "The Jeffersons." She is an honoree from the Hollywood Walk of Fame Class of 2021 and was awarded the star in the television category. Each year, Leo Robin Music awaits with great interest the release of the annual announcement by the Hollywood Chamber of the new class of honorees to have their stars unveiled and installed on the Hollywood Walk of Fame to see if the star awarded to lyricist Leo Robin 31 years ago but never installed finally appears on this list. For Leo Robin, this annual ritual is known as 'Pass Over.' Charlie Parker performing "f I Should Lose You," composed by Ralph Rainger with lyrics by Leo Robin, on his Charlie Parker With Strings album in 1949 and Marla Gibbs singing "Easy Living," composed by Ralph Rainger with lyrics by Leo Robin, in the style of Billie Holiday on the NBC sitcom 227 episode entitled "Blues" The contributions Leo Robin has made to The Great American Songbook are celebrated time and again with contemporary covers by artists including regularly by those appearing on the annual list of honorees. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

Mediaguide.Pdf

American Legion Baseball would like to thank the following: 2017 ALWS schedule THURSDAY – AUGUST 10 Game 1 – 9:30am – Northeast vs. Great Lakes Game 2 – 1:00pm – Central Plains vs. Western Game 3 – 4:30pm – Mid-South vs. Northwest Game 4 – 8:00pm – Southeast vs. Mid-Atlantic Off day – none FRIDAY – AUGUST 11 Game 5 – 4:00pm – Great Lakes vs. Central Plains Game 6 – 7:30pm – Western vs. Northeastern Off day – Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Mid-South, Northwest SATURDAY – AUGUST 12 Game 7 – 11:30am – Mid-Atlantic vs. Mid-South Game 8 – 3:30pm – Northwest vs. Southeast The American Legion Game 9 – Northeast vs. Central Plains Off day – Great Lakes, Western Code of Sportsmanship SUNDAY – AUGUST 13 Game 10 – Noon – Great Lakes vs. Western I will keep the rules Game 11 – 3:30pm – Mid-Atlantic vs. Northwest Keep faith with my teammates Game 12 – 7:30pm – Southeast vs. Mid-South Keep my temper Off day – Northeast, Central Plains Keep myself fit Keep a stout heart in defeat MONDAY – AUGUST 14 Game 13 – 3:00pm – STARS winner vs. STRIPES runner-up Keep my pride under in victory Game 14 – 7:00pm – STRIPLES winner vs. STARS runner-up Keep a sound soul, a clean mind And a healthy body. TUESDAY – AUGUST 14 – CHAMPIONSHIP TUESDAY Game 15 – 7:00pm – winner game 13 vs. winner game 14 ALWS matches Stars and Stripes On the cover Top left: Logan Vidrine pitches Texarkana AR into the finals The 2017 American Legion World Series will salute the Stars of the ALWS championship with a three-hit performance and Stripes when playing its 91st World Series (92nd year) against previously unbeaten Rockport IN.