Chinese Women's Migration to Southeast Asia Since 1978

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symptoms and Survivorship

SYMPTOMS AND SURVIVORSHIP 12000 Oral Abstract Session, Fri, 8:00 AM-11:00 AM Multisite randomized trial of integrated palliative and oncology care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Areej El-Jawahri, Thomas William LeBlanc, Alison Kavanaugh, Jason Webb, Vicki A. Jackson, Toby Christopher Campbell, Nina O’Connor, Selina M. Luger, Ellin Gafford, Jillian Gustin, Bhavana Bhatnagar, Amir Tahmasb Fathi, Gabriela Hobbs, Julia Foster, Showly Nicholson, Debra M. Davis, Hilena Addis, Dagny Vaughn, Nora K. Horick, Jennifer Temel; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Duke University, Durham, NC; University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, Madison, WI; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH; Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Division of Hematology, Columbus, OH; Massachu- setts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, NC; Massachusetts General Hospital Biostatistics Center, Boston, MA Background: Patients with AML receiving intensive chemotherapy experience substantial decline in their quality of life (QOL) and mood during their hospitalization for induction chemotherapy and often receive aggressive care at the end of life (EOL). We sought to examine the effect of integrated palliative and oncology care on QOL, mood, post-traumatic stress (PTSD) symptoms, and EOL outcomes in patients with AML. Methods: We conducted a multi-site randomized trial of integrated palliative and oncology care (n = 86) versus usual oncology care (n = 74) for patients with AML undergoing intensive chemotherapy. Patients assigned to the intervention were seen by palliative care clinicians at least twice per week during their hospitalization for induction chemotherapy and all subsequent hospital- izations. -

120 China Minzhong Food Corporation Limited

CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CORPORATION LIMITED CORPORATION FOOD MINZHONG CHINA CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CORPORATION LIMITED CORPORATION LIMITED (Company Registration Number: 200402715N) National Leading Dragon Head Enterprise 229 Mountbatten Road #02-05 Mountbatten Square Singapore 398007 Tel : (65) 6346 7506 2015 REPORT ANNUAL Fax : (65) 6346 0787 Web : www.chinaminzhong.com Email : [email protected] AN 015 NUAL REPORT 2 CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors Head Office Mr. Lin Guo Rong Sanshan Village, Xitianwei Town (Executive Chairman and Chief Executive Officer) Licheng District, Putian City Mr. Siek Wei Ting Fujian Province (Executive Director and Chief Financial Officer) People’s Republic of China (Postal Code 351131) Mr. Hendra Widjaja (Non-Executive and Non-Independent Director) Solicitors Mr. Kasim Rusmin Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP (Alternate Director to Mr. Hendra Widjaja) 9 Battery Road #25-01 Mr. Goh Kian Chee The Straits Trading Building (Non-Executive and Independent Director) Singapore 049910 Mr. Lim Yeow Hua (Non-Executive and Independent Director) External Auditors Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Crowe Horwath First Trust LLP (Non-Executive and Independent Director) 8 Shenton Way #05-01 AXA Tower Audit Committee Singapore 068811 Mr. Lim Yeow Hua (Chairman) Partner-in-charge: Alfred Cheong Keng Chuan Mr. Hendra Widjaja (Appointed since 2011) Mr. Goh Kian Chee Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Internal Auditors BDO LLP Remuneration Committee 21 Merchant Road #05-01 Mr. Goh Kian Chee (Chairman) Singapore 058267 Mr. Hendra Widjaja Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Partner-in-charge: Koh Chin Beng (Appointed since 2015) Nominating Committee Mr. Goh Kian Chee (Chairman) Principal Bankers Mr. Hendra Widjaja Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Mr. -

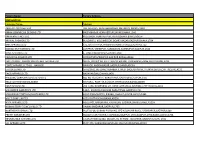

Annual Report 2019

DIGITALISATION ENERGY AUTOMATION INNOVATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 PERFORMANCE KION Group 2 Key figures for 2019 KION Group overview Change in € million 2019 2018 2017 * 2019 / 2018 Order intake 9,111.7 8,656.7 7,979.1 5.3% Revenue 8,806.5 7,995.7 7,598.1 10.1% Order book ¹ 3,631.7 3,300.8 2,614.6 10.0% Financial performance EBITDA 1,614.6 1,540.6 1,457.6 4.8% Adjusted EBITDA ² 1,657.5 1,555.1 1,495.8 6.6% Adjusted EBITDA margin ² 18.8% 19.4% 19.7% – EBIT 716.6 642.8 561.0 11.5% Adjusted EBIT ² 850.5 789.9 777.3 7.7% Adjusted EBIT margin ² 9.7% 9.9% 10.2% – Net income 444.8 401.6 422.5 10.7% Financial position ¹ Total assets 13,765.2 12,968.8 12,337.7 6.1% Equity 3,558.4 3,305.1 2,992.3 7.7% Net financial debt 1,609.3 1,869.9 2,095.5 – 13.9% ROCE ³ 9.7% 9.3% 9.3% – Cash flow Free cash flow 4 568.4 519.9 474.3 9.3% Capital expenditure 5 287.4 258.5 218.3 11.2% Employees 6 34,604 33,128 31,608 4.5% 1 Figures as at balance sheet date 31/12/ 2 Adjusted for PPA items and non-recurring items 3 ROCE is defined as the proportion of adjusted EBIT to capital employed 4 Free cash flow is defined as cash flow from operating activities plus cash flow from investing activities 5 Capital expenditure including capitalised development costs, excluding right-of-use assets 6 Number of employees (full-time equivalents) as at balance sheet date 31/12/ * Key figures for 2017 were restated due to the initial application of IFRS 15 and IFRS 16 All amounts in this annual report are disclosed in millions of euros (€ million) unless stated otherwise. -

The Production and Developing Trace of the Xingnuo Parade on The

2019 4th International Conference on Education Science and Development (ICESD 2019) ISBN: 978-1-60595-593-3 The Production and Developing Trace of the Xingnuo Parade on the Lantern Festival in Putian—Take Nanpu Village in Putian as an Example Fang-Huan YANG School of Physical Education and Sport Science, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, Fujian China Keywords: Lantern Festival, Xingnuo Parade, Developing Trace Abstract. The Xingnuo parade in Putian city is a folk activity among many performances during the traditional Lantern Festival. It plays an important role in terms of creating strong, diverse and interesting festival atmosphere, and brings great inspiration to people. With the development of the society, people's ideas have been changing, along with the improvement of the cultural level. At the same time, the Xingnuo parade activities have been changing too. Taking the Nanpu village in Putian as an example, this article introduces the production and developing trace of the Xingnuo parade on the Lantern Festival in Putian, to show the influence of traditional culture on the formation of the Xingnuo parade and display the unique value of traditional culture in modern economic activities. 1. Introduction The 15th day of the first month of the lunar calendar is the Lantern Festival in China, but in Putian, Fujian, the Lantern Festival starts from the 1st till the 29th of the first lunar month. It lasts for nearly a month and is called the "Longest Lantern Festival in China" [1]. The Xingnuo parade in Nanpu Village, Putian during the Lantern Festival is a kind of folk activity that connects one or several neighborhood natural villages in the form of sacrificial ceremonies and folk performances, and involves many people. -

Stroke of a Cardiac Myxoma Origin Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2015;30(2):225-34

Yuan SM & HumuruolaREVIEW G ARTICLE - Stroke of a cardiac myxoma origin Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2015;30(2):225-34 Stroke of a cardiac myxoma origin Acidente vascular cerebral com origem em mixoma cardíaco Shi-Min Yuan1, MMed, PhD; Gulimila Humuruola2, MD DOI 10.5935/1678-9741.20150022 RBCCV 44205-1636 Abstract magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and echocardiography Objective: The clinical features of cardiac myxoma stroke are imperative for young stroke patients in identifying the cere- have not been sufficiently described. Debates remain concern- bral infarct and determining the stroke of a cardiac origin. Im- ing the options and timing of treatment and the clinical out- mediate thrombolytic therapy may completely resolve the cere- comes are unknown. This article aims to highlight the pertinent bral stroke and improve the neurologic function of the patients. aspects of this rare condition. An early surgical resection of cardiac myxoma is recommended Methods: Data source of the present study came from a in patients with not large territory cerebral infarct. comprehensive literature collection of cardiac myxoma stroke Descriptors: Embolism. Middle Cerebral Artery. Myxoma. in PubMed, Google search engine and Highwire Press for the Stroke. year range 2000-2014. Results: Young adults, female predominance, single cere- bral vessel (mostly the middle cerebral artery), multiple terri- Resumo tory involvements and solitary left atrial myxoma constituted Objetivo: As características clínicas do acidente vascular the outstanding characteristics of this patient setting. The most cerebral causado por mixoma cardíaco não foram descritas common affected cerebral vessel (the middle cerebral artery) suficientemente. Debates permanecem sobre as opções e o mo- and areas (the basal ganglion, cerebellum and parietal and mento de tratamento e os resultados clínicos são desconheci- temporal regions) corresponded well to the common manifesta- dos. -

Canada Du Canada Acquisitions and Direclion Des Acquisitions El Bibliographie Services Branch Des Ser

Nalionallibrary Bibliothèque nationale .+. 01 Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direclion des acquisitions el Bibliographie Services Branch des ser.. ices bibliographiques 395 Wellinglon Street 395. rue Wellington Onawa, OntarIO Ollawa (Onlario) K1A0I'4 KIAON4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualité de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the dépend grandement de la qualité quality of the original thesis de la thèse soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualité ensure the highest quality of supérieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec l'université degree. qui a conféré le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualité d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser à pages were typed with a poor désirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont été university sent us an inferior dactylographiées à l'aide d'un photocopy. ruban usé ou si l'université nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualité inférieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, même partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, à la Loi canadienne sur le droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 197Q, c. C-30, et subsequant amendments. ses amendements subséquents. Canada • Gcnder Perl'ormatlvity and Ritual Performance in South-east China Samantha Anderson Department of East Asian Studies McGillUniversity, Montreal March 1996 A thesls submitted ta the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master's of Arts © Samantha Anderson 1996 • National Library Bibliothèque nationale .+. -

3. 10 SHANTY � Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4

Disc Bola 1. Judika Sakura (4:12) 2. Firman Esok Kan Masih Ada (3:43) 3. 10 SHANTY Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4. 14 J ROCK Topeng Sahabat (4:53) 5. Tata AFI Junior feat Rio Febrian There's A Hero (3:26) 6. DSDS Cry On My Shoulder (3:55) 7. Glenn Pengakuan Lelaki Ft.pazto (3:35) 8. Glenn Kisah Romantis (4:23) 9. Guo Mei Mei Lao Shu Ai Da Mi Lao Shu Ai Da Mi (Original Version) (4:31) 10. Indonesian Idol Cinta (4:30) 11. Ismi Azis Kasih (4:25) 12. Jikustik Samudra Mengering (4:24) 13. Keane Somewhere Only We Know (3:57) 14. Once Dealova (4:25) 15. Peterpan Menunggu Pagi [Ost. Alexandria] (3:01) 16. PeterPan Tak Bisakah (3:33) 17. Peterpan soundtrack album menunggu pagi (3:02) 18. Plus One Last Flight Out (3:56) 19. S Club 7 Have You Ever (3:19) 20. Seurieus Band Apanya Dong (4:08) 21. Iwan Fals Selamat Malam, Selamat Tidur Sayang (5:00) 22. 5566 Wo Nan Guo (4:54) 23. Aaron Kwok Wo Shi Bu Shi Gai An Jing De Zou Kai (3:57) 24. Abba Chiquitita (5:26) 25. Abba Dancing Queen (3:50) 26. Abba Fernando (4:11) 27. Ace Of Base The Sign (3:09) 28. Alanis Morissette Uninvited (4:36) 29. Alejandro Sanz & The Corrs Me Iré (The Hardest Day) (4:26) 30. Andy Lau Lian Xi (4:24) 31. Anggun Look Into Yourself (4:06) 32. Anggun Still Reminds Me (3:50) 33. Anggun Want You to Want Me (3:14) 34. -

123Rd Annual Commencement California Institute of Technology June 16, 2017

123rd Annual Commencement california institute of technology June 16, 2017 The passing of the torch symbolizes the spirit of research going from one hand to the next, from one generation to the next, from youth to maturity. commencement.caltech.edu 123rd Annual Commencement CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Friday, June 16, 2017 10:00 a.m. ACADEMIC PROCESSION Chief Marshal Warren C. Brown, Ph.D. Marshals Shuki Bruck, Ph.D. Richard C. Flagan, Ph.D. David Prober, Ph.D. Douglas C. Rees, Ph.D. Peter Schröeder, Ph.D. Faculty Officers Kristine L. Haugen, Ph.D. Mary B. Kennedy, Ph.D. Marching Order Candidates for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Candidates for the Degree of Master of Science Candidate for the Degree of Engineer Candidates for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty Officers The Faculty The Chairs of the Divisions The Deans The Vice Provosts The Provost The Vice Presidents The Trustees The Commencement Speaker The President The Chair of the Board of Trustees 3 PROGRAM Organ Prelude Leslie J. Deutsch, Ph.D. Processional The Caltech Convocation Brass and Percussion Ensemble Glenn D. Price, DMA, Conductor Presiding David L. Lee, Ph.D. Chair of the Board of Trustees California Institute of Technology Commencement Speaker Dr. Mae C. Jemison Physician, Engineer, NASA Astronaut Choral Selection The Caltech Glee Club, the Caltech “Ode to Joy” excerpts from Convocation Brass and Percussion Symphony No. 9 Ensemble, and Organ by Ludwig van Beethoven; Nancy Sulahian, M.M., Conductor Arranged by Dr. Deutsch (Translation on page 59.) Conferring of Degrees Thomas F. Rosenbaum, Ph.D. -

NOW SHOWING 86 Q+A 88 New This Month 90 Movies 92 Television 94 Audio

NOW SHOWING 86 Q+A 88 New this month 90 Movies 92 Television 94 Audio On board this month, the most talked about film of the year: Parasite. And we catch up with the film‘s Oscar-winning director, Bong Joon-ho New releases Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker Spies in Disguise The Good Liar MALAYSIAAIRLINES.COM 85 Now Showing Q A Your previous movies, such as Snowpiercer and Okja, were primarily in English. Why did you decide to make Parasite in Korean? It was a very natural decision. I am based in Seoul, so I wanted to tell the story of the people and neighbourhoods around me; the people I am around and encounter daily. And for that to be authentic, it needed to be in Korean. So much of Parasite revolves around themes relating to class. At what point did you become class-conscious? I think all directors, artists and creatives are interested in class at some level. We all look at people we encounter and wonder how rich they are. We wonder about these sorts of things because we live in an era of capitalism. It’s not like we had a big meeting and said this movie needs to be focused on class, it’s just something that naturally happened. She is smart, the sort of person who Making would have done well at school. She just 3 more movies You took ideas from your experiences trusts people too easily. She has lived a while at college and used them in the very sheltered life in terms of marrying that had us on movie. -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

MAZU WORSHIP IN LATE IMPERIAL CHINA: GENDER, POLITICS, RELIGION, AND IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION By YANCHAO ZHANG A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Yanchao Zhang To people I love ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As this dissertation has taken shape over the past few years, some individuals and organizations have provided all kinds of support for me throughout its different stages. Since I started my doctorial study in Religion Department of University in 2011, I have received full support from my advisor, Dr. Mario Poceski. I deeply appreciate all his helps in both academic and personal lives. During the past few years, I took many courses with Dr. Poceski that laid foundation for my dissertation project. In addition, he continued offering guidance and feedback throughout my dissertation research and writing. Dr. Poceski also read and commented in detail on earlier versions of my dissertation. His consistent support and helpful feedback were crucial in completing my dissertation. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have him as my advisor. I would also like to thank the other wonderful members of my dissertation committee for supporting me and working with me since I started my dissertation proposal. First, I own a big debt of gratitude to Dr. Richard Wang for helping me with translating the classic Chinese texts featuring Mazu into English. He also read and commented on the chapter of Daoist canonization. I have benefited a lot from his rich knowledge on Daoism and Chinese culture. -

Astract Viktor Emile Frankl's Meaning Paradigm

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary ASTRACT VIKTOR EMILE FRANKL’S MEANING PARADIGM: LOGOTHERAPY AS A MODEL FOR MEANING-CENTERED PASTORAL MINISTRY IN THE CONTEMPORARY SINGAPOREAN CONTEXT Peter Wong Keen Mun This dissertation examined Viktor Frankl’s works published in English and assessed logotherapy as a model for meaning-centered pastoral ministry in the contemporary Singaporean context. The project explored four composite case studies portraying experiences observed in Singapore. Each case study was constructed from a composite of personalities and a matrix of events and drew from my knowledge of actual persons and experience of real-life scenarios. The studies were analyzed using logotherapy in a pastoral ministry setting. The cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes anticipated demonstrated the suitability of logotherapy as a model of meaning-centered pastoral ministry in the contemporary Singaporean context. DISSERTATION APPROVAL This is to certify that the dissertation entitled VIKTOR EMILE FRANKL’S MEANING PARADIGM: LOGOTHERAPY AS A MODEL FOR MEANING-CENTERED PASTORAL MINISTRY IN THE CONTEMPORARY SINGAPOREAN CONTEXT presented by Peter Wong Keen Mun has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for the DOCTOR OF MINISTRY degree at Asbury Theological Seminary ____________________________________ April 27, 2005 _ Mentor Date ____________________________________ April 27, 2005 _ Internal Reader Date ____________________________________ April 27, 2005 _ Vice President of Educational Development Date VIKTOR EMILE FRANKL’S MEANING PARADIGM: LOGOTHERAPY AS A MODEL FOR MEANING-CENTERED PASTORAL MINISTRY IN THE CONTEMPORARY SINGAPOREAN CONTEXT A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Asbury Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry by Peter Wong Keen Mun May 2005 © 2005 Peter Wong Keen Mun ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables…………………………………….……...……………………….………….