Body Centric Knowledge: Traditions of Performance and Pedagogy in Kathakali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Details of Crushers in Palakkad District As on Date of Completion of Quarry

Details of crushers in Palakkad District as on date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator Alathur Taluk Aboobacker.V.K, Manager, Aboobacker.V.K, Manager, Malaboor Blue Stone, Malaboor Blue Stone, 523 Kuzhalmannam-II Pullupara Kalapetty. P.O, Kalapetty. P.O, Kuzhalmannam, Palakkad, Kuzhalmannam, Palakkad, Chittur Taluk K.P.Anto, KGP Granites, KGP Granites, K.P.Anto, KGP Granites, 495 Valiyavallampathy Ravanankunnupara Ravanankunnupara, Ravanankunnupara, Ravanankunnupara, P.O.Nattukal P.O.Nattuka P.O.Nattukal Ottapalam Taluk K.abdurahamn, Managing K.abdurahamn, Managing Cresent Stone Creshers, 102 Kulukallur Vandanthara Partner, Crescent Stone Partner, Crescent Stone Mannengod Crusher, Mannengod Crusher, Mannengod New Hajar Indusrties, K.Ummer, Managing 122 Nagalasserry Mooliparambu Partner, Moolipparambu, Kottachira.P.O, Palakkad Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal Antony S. Alukkal, Alukkal 125 Thirumittakode II Malayan House, P.O. Kalady, House, P.O. Kalady, House, P.O. Kalady, Ernakulam Ernakulam Ernakulam Abdul Hammed Khan, Jamshid Industries 137 Nagalasserry Kodanad Crusher Unit, Mezhathoor .P.O, Palakkad Abdul Hameed Khan, Abdul Hameed Khan, Abdul Hameed Khan, Jamshid Industries, Crusher Jamshid Industries, Jamshid Industries, 145 Nagalasserry Kodanadu Unit, Mezhathoor.P.O, Crusher Unit, Crusher Unit, Palakkad Mezhathoor.P.O, Palakkad Mezhathoor.P.O, Palakkad Marcose George, Geosons Aggregates, Benny Abraham, 164 Koppam Amayur Cherukunnel, P.O.Amayur, P.O.Amayur Ernakulam Muhammedunni Haji, Muhammedunni Haji, Mabrook Granites, Mabrook Granites,Mabrook Mabrook Granites, 168 Thrithala kottappadom Mabrook Industrial Estate, Industrial Estate, Mabrook Industrial Estate, Kottappadom, Palakkad Kottappadom, Palakkad, Kottappadom, Palakkad, V.V. Divakaran, Sreekrishna V.V. Divakaran, 171 Kappur Kappur Industries, Kalladathoor, Sreekrishna Industries, Palakkad Kalladathoor, Palakkad © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. -

THE DIVISION of CONTINUING EDUCATION and COMMUNITY SERVICE the STATE FOUNDATION on CULTURE and the ARTS and the UNIVERSITY THEATRE Present

THE DIVISION OF CONTINUING EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY SERVICE THE STATE FOUNDATION ON CULTURE AND THE ARTS AND THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE present by special arrangements with the American Society for Eastern Arts San Francisco, California John F. Kennedy Theatre University of Hawaii September 24, 25, 1970 /(ala mania/am /(aiAahali Company The Kerala Kalamandalam (the Kerala State Academy of the Arts) was founded in 1930 by ~lahaka vi Vallathol, poet laureate of Kerala, to ensure the continuance of the best tradi tions in Kathakali. The institution is nO\\ supported by both State and Central Governments and trains most of the present-day Kathakali actors, musicians and make-up artists. The Kerala Kalamandalam Kathakali company i::; the finest in India. Such is the demand for its performances that there is seldom a "night off" during the performing season . Most of the principal actors are asatts (teachers) at the in::;titution. In 1967 the com pany first toured Europe, appearing at most of the summer festi vals, including Jean-Louis Barrault's Theatre des Nations and 15 performances at London's Saville Theatre, as well as at Expo '67 in Montreal. The next year, they we re featured at the Shiraz-Persepolis International Festival of the Arts in I ran. This August the Kerala Kalamandalam company performed at Expo '70 in Osaka and subsequently toured Indonesia, Australia and Fiji. This. their first visit to the Cnited States, is presented by the American Society for Eastern Arts. ACCOMPANISTS FOR BOTH PROGRAMS Singers: Neelakantan Nambissan S. Cangadharan -

Page 1 of 30 SL NO BILL UNIT STN EMPNO EMPNAME DESIGN

Page 1 of 30 SL NO BILL UNIT STN EMPNO EMPNAME DESIGN FATHERNAME RLYJOIN REIREMENT 1 0605001 PGT 15500326446 RAJALAKSHMI.N. AA K R NARAYANAN 08/04/1982 31/01/2021 2 0605001 PGT 15500328170 BALAKRISHNAN.C. AA R V MENON 02/01/1986 31/05/2025 3 0605001 PGT 15500653720 USHADEVI.A. AA ACHUTHAN 20/05/1985 31/05/2026 4 0605001 PGT 15501095973 ANILKUMAR.J. AA T V JAMES 15/09/1982 31/05/2020 5 0605001 PGT 15502311045 MURALI.N. AA K.NATARAJAN 28/12/1990 31/05/2025 6 0605001 PGT 15502311203 GOPALAKRISHNAN.R. AA M.K.RAMACHANDRAN 09/04/1991 30/06/2026 7 0605001 PGT 15502503130 SIVADASAN.P.M. AA K.K.K.PANICKAR 27/09/1989 31/03/2023 8 0605001 PGT 15502589072 SOBHA.G. AA M N G NAIR 01/08/1979 28/02/2021 9 0605001 PGT 15502589102 SOBHANA.P. AA N.K.NAIR 14/08/1980 31/05/2022 10 0605001 PGT 15502589199 DEVARAJ.P.K. AA V HARIHARAN 18/02/1981 31/05/2020 11 0605001 PGT 15502589205 KHALEEDAHAMED.T.M. AA M A KHADER 23/02/1981 30/04/2020 12 0605001 PGT 15502589333 BALASUBRAMANIAN.N. AA M.N.NAIR 29/04/1981 30/11/2021 13 0605001 PGT 15502589369 KRISHNAMOORTHY.K.V. AA K.V.SUBBARAYALU 08/04/1981 31/05/2020 14 0605001 PGT 15502589412 HARIDASAN.K.K. AA KANDUNNY 25/03/1982 31/10/2022 15 0605001 PGT 15502589527 PRASANNA.P.E. AA P.K.KRISHNAN 21/06/1983 31/12/2019 16 0605001 PGT 15502982651 SHYLAJA.A.V. -

Kutiyattam: Living Heritage,’ Submitted by the Undersigned Research Team Was Carried out Under My Supervision

KutyatamLiving Heritage March 2016 Discover India Program 2015-16 List of Students Name Responsibilities Signature Aravind Finance and 1. Chandrasekaran On-Field Interviews 2. Arnav Jha Head of Content Writing Group Leader and 3. Arundhati Singh Head of Videography Content Writing and 4. Ayesha Selwyn On-Field Interviews 5. Daveed Kuruvilla Content Writing Logistics and 6. Delnaz Kabrajee Photography Photography and 7. Heet Shah Videography Transcriptions and 8. Kavya Pande On-Field Interviews in Delhi Head of Photography 9. Pallavi Rajankar and Design 10. Siddhant Jain Videography Finance and 11. Simran Khanna On-Field Interviews i Authentication Certificate This is to certify that the work incorporated in this report, titled ‘Kutiyattam: Living Heritage,’ submitted by the undersigned Research Team was carried out under my supervision. The information obtained from other sources has been duly acknowledged. Name Signature 1. Aravind Chandrasekaran 2. Arnav Jha 3. Arundhati Singh 4. Ayesha Selwyn 5. Daveed Kuruvilla 6. Delnaz Kabrajee 7. Heet Shah 8. Kavya Pande 9. Pallavi Rajankar 10. Siddhant Jain 11. Simran Khanna Name of Faculty Mentor: Professor Neeta Sharma Signature Date: 2 March 2016 ii Acknowledgments It would not have been possible to carry out this research project without the guidance and support of a number of people, who extended their valuable assistance in the preparation and completion of our study. We would like to take this opportunity to thank FLAME University for giving us the opportunity to carry out such extensive research at an undergraduate level. We would also like to thank Dr. Neeti Bose, Chair of the Discover India Program, and the entire DIP committee, for their guidance in the process of discovering India through our own lens. -

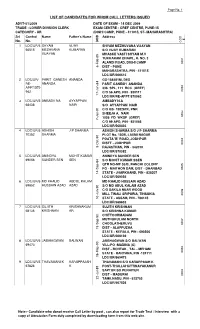

Ldc Final Merit

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED ADVT-01/2009 DATE OF EXAM - 14 DEC 2009 TRADE : LOWER DIVISION CLERK EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 CATEGORY - UR (DIGHI CAMP, PUNE - 411015, ST- MAHARASHTRA) Srl Control Name Father's Name Address E DOB No. No. COD 1 LDC/UR/5 SHYAM VIJAY SHYAM MEZHUVANA VIJAYAN 66515 MEZHVANA KUMARAN S/O VIJAY KUMARAN VIJAYAN MHASKE VASTI SHYAM M.V TUKKARAM CHAWL, R. NO. 3 ALANDI ROAD, DIGHI CAMP 0001 6-Feb-89 DIST - PUNE MAHARASHTRA, PIN - 411015 LDC/UR/566515 2 LDC/UR/ PARIT GANESH ANANDA GS-188481M, DES RE- ANANDA PARIT GANESH ANANDA APPT/570 336 SPL, 111 RCC (GREF) 962 C/O 56 APO, PIN - 930111 0002 17-Jun-84 LDC/UR/RE-APPT/570962 3 LDC/UR/5 ANBADV NA AYYAPPAN AMBADY N.A 68436 NAIR S/O AYYAPPAN NAIR C/O GS- 188267K, PNR SHEEJA A. NAIR 1056 FD WKSP (GREF) 0003 7-Jan-91 C/O 99 APO, PIN - 931056 LDC/UR/568436 4 LDC/UR/5 ASHISH J P SHARMA ASHISH SHARMA S/O J P SHARMA 70382 SHARMA PLOT No. 180B, LAXMI NAGAR POATA 'B' ROAD, JODHPUR DISTT - JODHPUR 0004 5-Oct-90 RAJASTHAN, PIN - 342010 LDC/UR/570382 5 LDC/UR/5 ANINDYA MOHIT KUMAR ANINDYA SUNDER SEN 69056 SUNDER SEN SEN S/O MOHIT KUMAR SSEN QTR NO-MF 53/B, RANCHI COLONY PO - MAITHON DAM, DIST - DHANBAD 0005 14-Sep-84 STATE - JHARKHAND, PIN - 828207 LDC/UR/569056 6 LDC/UR/5 MD KHALID ABDUL KALAM MD KHALID HUSSAIN AZAD 69652 HUSSAIN AZAD AZAD S/O MD ABUL KALAM AZAD C/O SAKILA NEAR WOOD MILL TINALI SRIPURIA, TINSUKIA 0006 10-Jun-90 STATE - ASSAM, PIN - 786145 LDC/UR/569652 7 LDC/UR/5 SUJITH KRISHNAKUM SUJITH KRISHNAN 68136 KRISHNAN AR S/O KRISHNA -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

Special Convocation Address by the Chancellor

Special Convocation Address by The Chancellor Dr. Justice K.G. Balakrishnan Dr. E. Sridharan Dr. Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair Shri. M.A. Baby Dr. Ramachandran Thekkedath Members of the Syndicate and Senate Distinguished Academics Ladies and Gentlemen 1 I have immense pleasure to participate in the Special Convocation convened by the Cochin University of Science and Technology to confer the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws on Justice K.G. Balakrishnan, Doctor of Science on Shri E. Sridharan and Doctor of Letters on Shri Ramankutty Nair. Let me, at the outset, compliment the academic community of the University on its initiative to honour these illustrious sons of Kerala in recognition of their invaluable contributions in their respective fields. These awardees do not need any introduction before this august assembly. Men of renown, they represent the highest levels in their chosen pursuits, namely Jurisprudence, Engineering and `Kathakali.' This Trinity of Achievers, I am happy to add, has done the country proud by their competence and commitment. Shri Balakrishnan has enshrined himself in the mind of every keralite by his elevation as the first Malayali to adorn the highest pedestal of justice in the country. Endowed with a keen sense of social purpose, his landmark judgments have been acclaimed by the entire nation. It is quite in the fairness of things that Shri Balakrishnan continues to serve the people as the Chairperson of the National Human Rights Commission. An Engineer of international repute, Shri E. Sreedharan has adorned several top positions with distinction. Hailing from Palakkad, Kerala, he rose to eminence through hard work and lofty motivation. -

Palakkad PALAKKAD

Palakkad PALAKKAD / / / s Category in s s e e Final e Y which Y Reason for Y ( ( ( Decision in 9 his/her 9 Final 9 1 1 appeal 1 - - house is - Decision 6 3 1 - - (Increased - 0 included in 1 (Recommen 1 3 3 relief 3 ) ) ) Sl Name of disaster Ration Card the Rebuild ded by the Relief Assistance e e o o o e r Taluk Village r amount/Red r N N N o No. affected Number App ( If not o Technically Paid or Not Paid o f f f uced relief e e in the e Competent b b b amount/No d Rebuild App d Authority/A d e e e l l change in a Database fill a ny other m e e i relief p p the column a reason) l p p amount) C A as `Nil' ) A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 Palakkad Akathethara T M SURENDREN 1946162682 yes Paid 2 Palakkad Akathethara DEVU 1946022862 yes Paid 3 Palakkad Akathethara PRASAD K 1946022923 yes Paid 4 Palakkad Akathethara MANIYAPPAN R 1946022878 yes Paid 5 Palakkad Akathethara SHOBHANA P 1946021881 yes Paid Not Paid 6 Palakkad Akathethara Seetha 1946022739 yes Duplication 7 Palakkad Akathethara SEETHA 1946022739 yes Paid 8 Palakkad Akathethara KRISHNAVENI K 1946158835 yes Paid 9 Palakkad Akathethara kamalam 1946022988 yes Paid 10 Palakkad Akathethara PRIYA R 1946132777 yes Paid 11 Palakkad Akathethara CHELLAMMA 1946022421 yes Paid Page 1 Palakkad 12 Palakkad Akathethara Chandrika k 1946022576 yes Paid 13 Palakkad Akathethara RAJANI C 1946134568 yes Paid KRISHNAMOORT 14 Palakkad Akathethara 1946022713 yes Paid HY N 15 Palakkad Akathethara Prema 1946023035 yes Paid 16 Palakkad Akathethara PUSHPALATHA 1946022763 yes Paid 17 Palakkad Akathethara KANNAMMA -

Department of Mohiniyattam

M. A. MOHINIYATTAM SYLLABI 2019 Department of Mohiniyattam DEPARTMENT OF MOHINIYATTAM SREE SANKARACHARYA UNIVERSITY OF SANSKRIT, KALADY PG PROGRAMME IN MOHINIYATTAM “SCHEME AND SYLLABUS” (Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation - OBTLE) APRIL 2019 Content Page No. 01. Preface 1 02. Programme Outcomes of SSUS 1 03. OBTLE Abbreviations 2 04. Program Specific Outcomes (PSOs) of Department 2 05. General Structure of MA Program 3 06. Semester-wise distribution of Courses 3 07. Semester-wise Course details 5 08. PMOM11001 Nritta aspects of Mohiniyattam (Practical) 9 09. PMOM11002 Musical Compositions in the Nritta aspects of Mohiniyattam (Practical) 12 10. PMOM11003 Abhinaya aspects in Balaramabharatham and Natyasastra (Theory) 15 11. PMOM11004 Vachikabhinaya in the Classical Performing arts of Kerala (Elective Theory) 19 12. PMOM11005 Literature of Mohiniyattam (Elective Theory) 22 13. PMOM11006 Hasta Viniyogas according to Hasthalakshana Deepika- Part I (Practical) 26 14. PMOM11007 Sopana aspects in Mohiniyattam (Practical) 29 15. PMOS11008 Nritya aspects of Mohiniyattam (Practical) 31 16. PMOS11008 Detailed study of South Indian Tala Systems (Practical) 34 17. PMOS11010 Eastern and western Aesthetics (Theory) 37 18. PMOS11011 General Introduction to Mohiniyattam (Elective ) 41 19. PMOS11012 Women Performing Arts of Kerala (Elective - Theory) 45 20. PMOM11013 Abhinaya aspects of Mohiniyattam Part I (Practical) 48 21. PMOM11014 Choreography and Make up (Practical) 52 22. PMOM11015 Research Methodology (Theory) 54 23. PMOM11016 Mohiniyattam and Other South Indian Performing arts (Elective) 57 24. PMOM11017 Music of Mohiniyattam (Elective - Theory) 61 25. PMOS11018 Abhinaya aspects of Mohiniyattam Part II (Practical) 65 26. PMOS11019 History of Indian Classical Dance (Theory) 69 27. PMOS11020 Dissertation 73 28. -

Cin Company DIN Director Page 1

Cin Company DIN Director U01100KL2007PTC020727 NADACKAL PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 1379983 JOY PAUL U01100KL2007PTC020727 NADACKAL PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 3165523 JANCY JOY U01100KL2009PTC024908 UDUMALAI PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 2735531 NAZAR KOOTINTAKAYIL U01100KL2009PTC024908 UDUMALAI PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 2735571 SALEEM UMMER U01100KL2009PTC024908 UDUMALAI PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 2735632 KAMALUDHEEN THOPPIL ANDEPUTTIL MOHAMED U01100KL2009PTC024908 UDUMALAI PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 2921624 RASHEED GEOGREEN FARMS AND PROPERTY U01100KL2010PLC026651 DEVELOPERSLIMITED 1811199 RAJESH KRISHNA GEOGREEN FARMS AND PROPERTY U01100KL2010PLC026651 DEVELOPERSLIMITED 2840813 SAJI KEZHAPLAKKAL GEOGREEN FARMS AND PROPERTY U01100KL2010PLC026651 DEVELOPERSLIMITED 2924333 DINESH SUBRAHMANIAN MERRY LAND PLANTATIONS & DEVELOPERSPRIVATE MADHAVAN PATTAYIL U01100KL2010PTC025528 LIMITED 2861460 CHOYIMUKKIL MERRY LAND PLANTATIONS & DEVELOPERSPRIVATE MOHANDAS KOYAPPA U01100KL2010PTC025528 LIMITED 2861596 PUTHUKATTIL U01100KL2010PTC026186 PRUDENT AGRO FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 1266984 ABDUL SALAM FAIZAL U01100KL2010PTC026186 PRUDENT AGRO FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 1267028 NOWFAL SALAM MADHU KORASSERRY U01100KL2010PTC026389 CIEL AGRO FARMS ANDPLANTATION PRIVATELIMITED 3031200 KAMALAKSHAN U01100KL2010PTC026389 CIEL AGRO FARMS ANDPLANTATION PRIVATELIMITED 3031206 MELVIN REBELLO U01100KL2010PTC026389 CIEL AGRO FARMS ANDPLANTATION PRIVATELIMITED 3039991 PRAKASH KESAVAN U01100KL2010PTC027098 KUTHANUR PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 155090 RAMESH NAIR U01100KL2010PTC027098 -

Raipur Kerala Samajam General Elections 2021 Voters List Name C.K

1/21/2021 raipurkeralasamajam.org/admin/action.php Raipur Kerala Samajam General Elections 2021 Voters List Name C.K. KORAH 1 Date Of Birth 06-Aug-40 Father/ Husband Name LATE SHRI C. KURUVILLA Ward TATIBANDH Address MIG-25, HOUSING BOARD COLONY Area TATIBANDH Mobile Number 9447845578 Membership Category Patron Member Name GOPA V. NAIR 2 Date Of Birth 30-May-64 Father/ Husband Name SHRI VISWAMBHARAN NAIR Ward INDUS AREA Address GOKULAM , VISHAL COLONY Area BIRGAON Mobile Number 9424200919 Membership Category Patron Member Name M.G. SOMAN PILLAI 3 Date Of Birth 27-May-47 Father/ Husband Name LATE MR. GOVINDAN PILLAI Ward TATIBANDH Address A-1/7, SECTOR -1 Area UDAYA NAGAR, TATIBANDH Mobile Number 9074792214 Membership Category Patron Member Name N. BAIJENDRA KUMAR I.A.S. 4 Date Of Birth 01-Jan-70 Father/ Husband Name Ward OUT OF RAIPUR Address Area Mobile Number Membership Category Patron Member Name P. JOY OOMMEN I.A.S. 5 Date Of Birth 01-Jan-70 Father/ Husband Name Ward OUT OF RAIPUR Address Area Mobile Number Membership Category Patron Member raipurkeralasamajam.org/admin/action.php 1/295 1/21/2021 raipurkeralasamajam.org/admin/action.php Name ROSAMMA SAMUEL 6 Date Of Birth 07-Dec-58 Father/ Husband Name SHRI J. SAMUEL Ward TATIBANDH Address HOUSE NO. 36, SANDEEP DAIRY FARM Area HIRAPUR Mobile Number Membership Category Patron Member Name A. P. UDAYAN 7 Date Of Birth 20-Mar-62 Father/ Husband Name LATE SHRI C. K. ACHUTHAN Ward DEVENDRA NAGAR Address P/24,DUBEY COLONY Area MOWA Mobile Number 8966909118 Membership Category Life Member Name ABHILASH K. -

Annexure-PFR File

APPLICATION FOR PRIOR ENVIRONMENTAL CLEARANCE (FORM-1M, PFR &EMP) (Submitted as per EIA Notification2006 & amended thereof) OF BUILDING STONE QUARRY OF M/S. MANNARKAD TALUK KARINGAL QUARRY OPERATORS VYAVASAYA SAHAKARANA SANGAM LTD Applied area: 0.8419 Ha (Non Forest Private Land) Production Capacity: 30,000 MT AT Re Survey No: 242/1A1, Pottassery 1 Village Mannarkkad Taluk, Palakkad District, Kerala FOR PROJECT PROPONENT Sri.C.H. Sakkariya President, Mannarakkad Taluk Karingal Quarry operators vyavasaya sahakarana sangam limited Palakkad District (D), Kerala – 678582 Email ID: [email protected] Phone No: 9744443057,8281729725 PREPARED BY Mr. NAZAR AHAMED K.V DMG/KERALA/RQP/7/2016 N SQUARE MINING & ENVIORMENTAL SOLUTIONS .LTD KARIMBANAKKAL BUILDING, P.O EDAPAL MALAPPURAM (Dist), KERALA-679576 Email:[email protected] Mobile No.8547097533, 9447177533 1 Table of Content Sl No Particulars Page No 1 FORM 1 M AND QUESTIONNAIRE 3-15 a. Basic Information 3-5 b. Activity 5-13 c. Environmental Sensitivity 14-15 2 PRE FEASIBILITY REPORT 16-61 a. Chapter 1 - Introduction 17 b. Chapter 2- Project Description 18-20 c. Chapter 3- Process Description 21-31 d. Chapter 4- Environmental Base-line Data Description 32-38 e. Chapter 5- Environmental Management Plan 38-51 f. Chapter 6- Risk Assessment & Disaster Management Plan 51-54 g. Chapter 7- Environmental Control Measures 54-59 ANNEXURES 1 By -Law of the Society, Certificate of Regn of By-law etc. 61-81 2 By-law Amendment Authorizing the President 82 3 ID Proof of the President 83 4 Possession Certificate 84 5 Consent from Land Owner 85-86 6 Land Documents 87-94 7 Letter of Intend, Old Quarry Permit 95-97 8 Lab Reports 98-103 9 RQP Certificate 104 10 Recent Photos of the Site 105 11 District Survey Report 106-192 FORM 1M (I) Basic Information Sl No.