Saving the Flagship Species of North-East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Saving the Flagship Species of North-East Asia

North-East Asian Subregional Programme for Environmental Cooperation (NEASPEC) SAVING THE FLAGSHIP SPECIES THE FLAGSHIP SAVING SAVING THE FLAGSHIP SPECIES OF NORTH-EAST ASIA OF NORTH-EAST ASIA United Nations ESCAP United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Environment and Sustainable Development Division United Nations Building Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Nature Conservation Strategy of NEASPEC Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel: (662) 288-1234; Fax: (662) 288-1025 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: <http://www.unescap.org/esd> United Nations ESCAP ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC ESCAP is the regional development arm of the United Nations and serves as the main economic and social development centre for the United Nations in Asia and the Pacific. Its mandate is to foster cooperation between its 53 members and 9 associate members. ESCAP provides the strategic link between global and country-level programmes and issues. It supports the Governments of the region in consolidating regional positions and advocates regional approaches to meeting the region’s unique socio-economic challenges in a globalizing world. The ESCAP office is located in Bangkok, Thailand. Please visit our website at www.unescap.org for further information. Saving the Flagship Species The grey shaded area of the map represents the members and associate members of ESCAP of North-East Asia: United Nations publication Nature Conservation Strategy of NEASPEC Copyright© United Nations 2007 ST/ESCAP/2495 -

2007 UNEP-WCMC Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas Lysenko I., Besançon C., Savy C

2007 UNEP-WCMC Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas Lysenko I., Besançon C., Savy C. No TBPA Name Country Protected Areas Sitecode Category PA Size, km 2 TBPA Area, km 2 Ellesmere/Greenland 1 Canada Quttinirpaaq 300093 II 38148.00 Transboundary Complex Greenland Hochstetter Forland 67910 RAMSAR 1848.20 Kilen 67911 RAMSAR 512.80 North-East Greenland 2065 MAB-BR 972000.00 North-East Greenland 650 II 972000.00 1,008,470.17 2 Canada Ivvavik 100672 II 10170.00 Old Crow Flats 101594 IV 7697.47 Vuntut 100673 II 4400.00 United States Arctic 2904 IV 72843.42 Arctic 35361 Ia 32374.98 Yukon Flats 10543 IV 34925.13 146,824.27 Alaska-Yukon-British Columbia 3 Canada Atlin 4178 II 2326.95 Borderlands Atlin 65094 II 384.45 Chilkoot Trail Nhp 167269 Unset 122.65 Kluane 612 II 22015.00 Kluane Wildlife 18707 VI 6450.00 Kluane/Wrangell-St Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek 12200 WHC 31595.00 Tatshenshini-Alsek 67406 Ib 9470.26 United States Admiralty Island 21243 Ib 3803.76 Chilkat 68395 II 24.46 Chilkat Bald Eagle 68396 II 198.38 Glacier Bay 1010 II 13045.50 Glacier Bay 22485 V 233.85 Glacier Bay 35382 Ib 10784.27 Glacier Bay-Admiralty Island Biosphere Reserve 11591 MAB-BR 15150.15 Kluane/Wrangell-St Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek 2018 WHC 66796.48 Kootznoowoo 101220 Ib 3868.24 Malaspina Glacier 21555 III 3878.40 Mendenhall River 306286 Unset 14.57 Misty Fiords 21247 Ib 8675.10 Misty Fjords 13041 IV 4622.75 Point Bridge 68394 II 11.64 Russell Fiord 21249 Ib 1411.15 Stikine-LeConte 21252 Ib 1816.75 Tetlin 2956 IV 2833.07 Tongass 13038 VI 67404.09 Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas ©2007 UNEP-WCMC 1 of 78 No TBPA Name Country Protected Areas Sitecode Category PA Size, km 2 TBPA Area, km 2 Tracy Arm-Fords Terror 21254 Ib 2643.43 Wrangell-St Elias 1005 II 33820.14 Wrangell-St Elias 35387 Ib 36740.24 Wrangell-St. -

EDGE of EXISTENCE 1Prioritising the Weird and Wonderful 3Making an Impact in the Field 2Empowering New Conservation Leaders A

EDGE OF EXISTENCE CALEB ON THE TRAIL OF THE TOGO SLIPPERY FROG Prioritising the Empowering new 10 weird and wonderful conservation leaders 1 2 From the very beginning, EDGE of Once you have identified the animals most in Existence was a unique idea. It is the need of action, you need to find the right people only conservation programme in the to protect them. Developing conservationists’ world to focus on animals that are both abilities in the countries where EDGE species YEARS Evolutionarily Distinct (ED) and Globally exist is the most effective and sustainable way to Endangered (GE). Highly ED species ensure the long-term survival of these species. have few or no close relatives on the tree From tracking wildlife populations to measuring of life; they represent millions of years the impact of a social media awareness ON THE of unique evolutionary history. Their campaign, the skill set of today’s conservation GE status tells us how threatened they champions is wide-ranging. Every year, around As ZSL’s EDGE of Existence conservation programme reaches are. ZSL conservationists use a scientific 10 early-career conservationists are awarded its first decade of protecting the planet’s most Evolutionarily framework to identify the animals that one of ZSL’s two-year EDGE Fellowships. With Making an impact are both highly distinct and threatened. mentorship from ZSL experts, and a grant to set in the field Distinct and Globally Endangered animals, we celebrate 10 The resulting EDGE species are unique up their own project on an EDGE species, each 3 highlights from its extraordinary work animals on the verge of extinction – the Fellow gains a rigorous scientific grounding Over the past decade, nearly 70 truly weird and wonderful. -

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES These Questions Are Indicative Only

MOST IMPORTANT TOPICS AND STUDY MATERIAL FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES These questions are indicative only. Not a complete list; For complete coverage, refer Textbook for Environmental Studies For Undergraduate Courses of all Branches of Higher Education by Erach Bharucha Part A: Important Questions (2 marks; one or two sentences) 1. Renewable resources 2. Non renewable resources 3. Ecosystem 4. Food chain 5. Food web 6. Energy pyramid 7. Estuary 8. Biodiversity 9. Climate change 10. Global warming 11. Acid rain 12. Population explosion 13. AIDS 14. Infectious diseases 15. Environmental health Part B Important Questions (5 marks; one page write up) 1. Difference between renewable and non renewable energy resources 2. Structure and functions of an ecosystem Eg Aquatic Ecosystem; Marine ecosystem etc 3. Food chains (elaborate with diagram and relationship) 4. Grassland ecosystem (elaborate with diagram and relationship) 5. Genetic, Species, Ecosystem Diversity 6. Hotspots Of Biodiversity 7. Threats To Biodiversity 8. Conservation Of Biodiversity 9. Solid Waste Management 10. Role Of Individuals In Pollution Prevention 11. Disaster Management 12. From Unsustainable To Sustainable Development 13. Urban Problems Related To Energy 14. Climate change and global warming 15. Environmental And Human Health 16. Role Of Information Technology In Environment And Human Health 17. Solid waste management 18. Vermicomposting Part C: Major questions 14 marks 4 pages write up 1. Different types of natural resources 2. Explain about forest resources 3. Structure and functions of any one of the ecosystem in details; Most important ecosystems are (a) aquatic ecosystem (b) marine ecosystem (c) and forest ecosystem. 4. Producers, Consumers and Decomposers-Details with examples 5. -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

Historical Diary 3 - February 1952

1ST MARINE AIR WING - HISTORICAL DIARY 3 - FEBRUARY 1952 Korean War Korean War Project Record: USMC-201 CD: 03 United States Marine Corps History Division Quantico, Virginia Records: United States Marine Corps Unit Name: 1st Marine Division Records Group: RG 127 Depository: National Archives and Records Administration Location: College Park, Maryland Editor: Hal Barker Korean War Project P.O. Box 180190 Dallas, TX 75218-0190 http://www.koreanwar.org DECLASSIFIED Korean War Project USMC-00318125 \l\i J 1\1 V \1 II \I r:'.._} """'· - . .-' '- r~ J\ 1 I '" L-,'-'<IL• DATr2 ufEB JSS2 SECRET / DECLASSTFTED DECLASSIFIED Korean War Project USMC-00318126 E;!0CijOSUH}-:: (l) to lBl J·.-U.\1 - w ... JJIO>. Gontitu~ 0 1c:'.. ~- -- ... ...... ··-- -- ·--· -· ... - ~-- --- ...... ~ ... ~-- -- ~--· ~~ -- -- - - - ·- - . -- - -- - -· -- -- ~·or u1l1tnl'Y purpOfh;f.l, th1G 1r: n nost 1''\VO!'".b1o hr~ola fron \·Jhich to cxpnnd, r>.nd ono ui tll \'ihioh tho ;_rnitcU. Stntv~ cord(l not cor.1pctc.~~~ The G1r;nlf1onnt VOYCI[;O of tho "Cotlotll cm:nh·•oi~.CG t.Lnt r,lliocl control o:f the ocoetno rtnd the Pl\nt..ttlfl nnd Guo?, Cr.n'llB cnnnot <'l"cvont the Sov1.ctfl fr•or!l trn nnfcr;r1 nc: their nnvnl f'Ol"'C'lcs fi•or:~ :r:urorcnn HtlDRi:t to Fnr En~ torn Ruor.iC~ nn t;Jwy ooc fit for pcr1oc3.o cw long nE; six ~--~Jnthn of tho 'J'Onr·. ~k....Qn.£!n t_l.~l'!l. A.c; of toUuy, th..: cr11,n b1l1 t1 ..:n of tLG '1 SSR to co n<luc t n111 ttLry Ol!DY'ntionn in trw vJ.r 1 n nrctlc nnd ~>ubnrt.t.ic onv.:\ronontEi nrc bul icV'"' to be qunnt1 tn tivoly nur-uriol" to tho .so of tho ·1 n11;el1 3tn. -

Geography, M.V

RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY FACULTY OF GEOGRAPHY, M.V. LOMONOSOV MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES No. 01 [v. 04] 2011 GEOGRAPHY ENVIRONMENT SUSTAINABILITY ggi111.inddi111.indd 1 003.08.20113.08.2011 114:38:054:38:05 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITORS-IN-CHIEF: Kasimov Nikolay S. Kotlyakov Vladimir M. Vandermotten Christian M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State Russian Academy of Sciences Université Libre de Bruxelles 01|2011 University, Faculty of Geography Institute of Geography Belgique Russia Russia 2 GES Tikunov Vladimir S. (Secretary-General) Kroonenberg Salomon, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Delft University of Technology Faculty of Geography, Russia. Department of Applied Earth Sciences, Babaev Agadzhan G. The Netherlands Turkmenistan Academy of Sciences, O’Loughlin John Institute of deserts, Turkmenistan University of Colorado at Boulder, Baklanov Petr Ya. Institute of Behavioral Sciences, USA Russian Academy of Sciences, Malkhazova Svetlana M. Pacific Institute of Geography, Russia M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Baume Otfried, Faculty of Geography, Russia Ludwig Maximilians Universitat Munchen, Mamedov Ramiz Institut fur Geographie, Germany Baku State University, Chalkley Brian Faculty of Geography, Azerbaijan University of Plymouth, UK Mironenko Nikolay S. Dmitriev Vasily V. M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Sankt-Petersburg State University, Faculty of Faculty of Geography, Russia. Geography and Geoecology, Russia Palacio-Prieto Jose Dobrolubov Sergey A. National Autonomous University of Mexico, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Institute of Geography, Mexico Faculty of Geography, Russia Palagiano Cosimo, D’yakonov Kirill N. Universita degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Instituto di Geografia, Italy Faculty of Geography, Russia Richling Andrzej Gritsay Olga V. -

Christmas in North Korea

Christmas in North Korea Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi With contributions from Talha Jilani Asad Alamgir Guven Uzun Suleman Khan Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Adnan I. Qureshi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5054-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5054-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors .............................................................................................. x Preface ...................................................................................................... xi 1. The Journey to North Korea ............................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction to the Korean Peninsula 1.2. Tour to North Korea 1.3. Introduction to The Pyongyang Times 1.4. Arrival at Pyongyang International Airport 2. Brief History ........................................................................................ 32 2.1. The ‘Three Kingdom’ and ‘Later Three Kingdom’ periods 2.2. Goryeo kingdom 2.3. Joseon kingdom 2.4. Japanese occupation 2.5. Complete Japanese control 2.6. Post-Japanese occupation 2.7. The Korean War 3. Contemporary North Korea .............................................................. 58 3.1. The first communist dynasty and its challenges 3.2. The changing face of the communist economic structure 3.3. Nuclear power 3.4. Rocket technology 3.5. Life amidst sanctions 3.6. Mineral resources 3.7. Mutual defense treaties 3.8. Governmental structure of North Korea 3.9. -

“Mongolia's Network of Managed Resource

GOVERNMENT OF MINISTRY OF MONGOLIA ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM “MONGOLIA’S NETWORK OF MANAGED RESOURCE PROTECTED AREAS” МОN/13/303 PROJECT THE PROJECT GOAL: The goal is to ensure integrity of Mongolia’s diverse ecosystems to secure viability of nation’s globally significant biodiversity. IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS: • Ministry of the Environment and Tourism THE PROJECT OBJECTIVE: • United Nations Development Program The project objective is to catalyze strategic expansion of Mongolia’s FUNDING: protected areas system through estab- • Global Environmental Facility – 1,309,091 $ lishment of a network of community • UN Development Program – 200,000 $ conservation areas covering • Ministry of the Environment and Tourism -500,000 $ (in-kind) under-represented terrestrial ecosystems. PROGRAMME PERIOD: TOTAL BUDGET: 2013-2018 1,509,091 $ PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION SITES: 1. “Gulzat” LPA (Uvs aimag, Bukhmurun soums) 203,316 ha 2. “Khavtgar” LPA (Batshireet soum of Khentii aimag) 104,900 ha 3. “Tumenkhan-shalz” LPA (Tsgaaan ovoo, Bayan-uul soums of Dornod aimag, and Norovlin soum of Khentii aimag) 374,499 ha Expanded area under local protection by 600 thousand ha: ACHIEVEMENTS AND OUTPUTS: Expanded area under local protection by about 600.0 thousand hectare and created ecological corridor areas Created under local protection, the ecological corridors/ connectivity support wildlife movement between the state and local pro- 1 tected areas in west and east regions. These are а. 433,9 thousand ha б. 278.9 thousand ha Total of 433,9 thousand ha area, a migration and calv- Argali sheep migration and distribution area of ing land of gazelle located between Tosonkhulstai NR 284.4 thousand ha, that connects Tsagaan shuvuut and Onon Balj NP in Bayan-uul, Tsagaan ovoo and Nor- and Turgen mountain SPAs in Sagil and Buhmurun ovlin soums of Dornod and Khenti aimags; soums of Uvs aimag. -

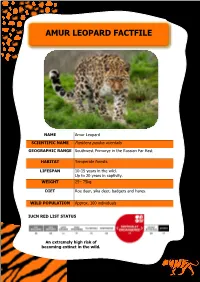

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species.