Informe De Avance Iabin Ecosystem Grant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of Biodiversity in Protected Areas of Shared Priority Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean

Inter-Agency Technical Committee of the Forum of Ministers of the Environment of Latin America and the Caribbean Twelfth Forum of Ministers of the Environment Distribution: of Latin America and the Caribbean Limited UNEP/LAC-IGWG.XII/TD.3 Bridgetown, Barbados 27 February, 2000 2nd to 7th March 2000 Original: English - Spanish A. Preparatory Meeting of Experts 2nd to 3rd March 2000 The World Bank United Nations Development Programme Conservation of Biodiversity in United Nations Protected Areas of Shared Environment Programme (ITC Coordinator) Priority Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Inter-American Development Bank Conservation and sustainable use of tropical rainforests of Latin America and the Caribbean This document was prepared by the Inter-Agency Technical Committee on the basis of the mandates of the Eleventh Meeting of the Forum of Ministers of the Environment of Latin America and the Caribbean (Lima, Peru, March 1998). The work was carried out by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), as the lead agencies, in coordination with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The purpose of the document is to provide the Forum with support for discussing and approving courses of action in the sphere of the Regional Action Plan for the period 2000-2001. UNEP/LAC-IGWG.XII/TD.4 Page i Table of Contents Chapter I. Conservation of Biodiversity in Protected Areas of Shared Priority Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean................................................. 1 I. Introduction................................................................................................ 1 II. Development of priority theme lines ................................................................ -

The Andean Mountain Cat (Oreailurus Jacobita) in the Central Andes: an Attempt of Status Assessment by Field Interviews

The Andean mountain cat (Oreailurus jacobita) in the central Andes: an attempt of status assessment by field interviews. Guillaume Chapron Laboratoire d'Ecologie CNRS, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 46 rue d'Ulm, 75230 Paris Cedex 05, France Very few is known about the Andean mountain cat in the Andes. I was able to conduct a preliminary survey in July 1998 in several protected areas in Chile and Bolivia. Here are the results. The information gathered on its repartition provides basis for further research. Travels by 4x4 covered 3.000 km at an altitude ranging from 2.400 INTRODUCTION to 5.000 m. Average temperatures encountered were 10°C during The Andean mountain cat (Oreailurus jacobita) is one of the the day and -20°C during the night. Wheather was almost sunny least poorly known felid species in the world (Nowell & Jackson, and windy. In Chile I visited all the Region I protected areas: Lauca 1996). Only few specimens are available in museums, often with National Park, Las Vicuñas National Reserve, Salar de Surire unprecise locations. It was first described in the genus Felis Natural Monument and Volcan Isluga National Park and, in Region (Cornalia, 1865) and placed later in the newly created genus II, the future Licancabur-Tatio National Park. It was not possible to Oreailurus (Cabrera, 1940). In 1973, Kuhn found on the basis of visit the Los Flamencos National Reserve but information the study of a single skull that a distinctive character was the concerning this protected area was collected in San Pedro de respective size of tympanic bullae chambers, the anterior being Atacama. -

7 Reasons to Visit Chile

7 reasons to visit Chile - Surprising natural wonders - Culture and Heritage - World-class Sports and Adventure - Flavors and Wine from the end of the world - Astronomical Tourism - Vibrant City Life - Health and Wellness By region (from North to South) these would be the places we (SAT Chile) most sell to our different markets: The North and The Atacama Desert - The Lauca National Park – Lake Chungara: UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve. - San Pedro de Atacama: The driest desert of the world, more than 375 natural attractions Santiago, Valparaíso and The Central Valleys - Casablanca: one of the 10 Greatest Wine Capitals of the world. - Valparaíso’s lifts and trolleybuses: living heritage. - Route of the Poets: Neruda’s houses on Negra Island and in Valparaíso, and Vicente Huidobro’s house in Cartagena. - Colchagua Valley: It has been dubbed “The Best Winemaking Region in the World” by the magazine Wine Enthusiast thanks to its world-classreds. Lakes and Volcanoes - Villarrica and Pucon: Thermal Springs Route: a large concentration of thermalsprings in the middle of the country’s natural landscape. - Pucón: an adventure sports paradise, offering kayak, rafting, trekking and volcano climbs Puerto Varas and Frutillar - Puyehue National Park, Vicente Pérez Rosales National Park and Alerce Andino National Park: southern forests and landscapes. - The Lakes Crossing: navigate along Todos los Santos Lake and make the crossing over to the Argentine city of Bariloche. Chiloé - 16 of Chiloé’s traditional churches are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. - -

The Origin and Emplacement of Domo Tinto, Guallatiri Volcano, Northern Chile Andean Geology, Vol

Andean Geology ISSN: 0718-7092 [email protected] Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Chile Watts, Robert B.; Clavero Ribes, Jorge; J. Sparks, R. Stephen The origin and emplacement of Domo Tinto, Guallatiri volcano, Northern Chile Andean Geology, vol. 41, núm. 3, septiembre, 2014, pp. 558-588 Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=173932124004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Andean Geology 41 (3): 558-588. September, 2014 Andean Geology doi: 10.5027/andgeoV41n3-a0410.5027/andgeoV40n2-a?? formerly Revista Geológica de Chile www.andeangeology.cl The origin and emplacement of Domo Tinto, Guallatiri volcano, Northern Chile Robert B. Watts1, Jorge Clavero Ribes2, R. Stephen J. Sparks3 1 Office of Disaster Management, Jimmit, Roseau, Commonwealth of Dominica. [email protected] 2 Escuela de Geología, Universidad Mayor, Manuel Montt 367, Providencia, Santiago, Chile. [email protected] 3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol. BS8 1RJ. United Kingdom. [email protected] ABSTRACT. Guallatiri Volcano (18°25’S, 69°05’W) is a large edifice located on the Chilean Altiplano near the Bo- livia/Chile border. This Pleistocene-Holocene construct, situated at the southern end of the Nevados de Quimsachata chain, is an andesitic/dacitic complex formed of early stage lava flows and later stage coulées and lava domes. -

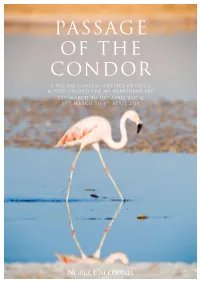

Passage of the Condor

PASSAGE OF THE CONDOR A PACIFIC COASTAL ODYSSEY OF CHILE & PERU ABOARD THE MS HEBRIDEAN SKY 25TH MARCH TO 10TH APRIL 2017 & 19TH MARCH TO 4TH APRIL 2018 Atacama Desert Sea Lion, Isla Ballestas ur coastal cruise along the Pacific shores of South America will be dominated by the ever present Andes as we make our way from central Chile to Peru. This is one of the world’s great expedition cruises. O ECUADOR Few regions in the world offer the diversity and ecosystems of those found in this intriguing part of South Guayaquil America. From the towering snow-capped Andes to barren coastal desert, the landscapes are unparalleled. PERU Our voyage takes us along the nutrient-rich Humboldt Current that is a haven for an amazing concentration Salaverry Lima of seabirds, marine mammals and wildlife. To highlight the wildlife, we will be visiting the Islas Ballestas Callao National Reserve, the Humboldt Penguin Nature Reserve and many other remote coastal sites and islands. Isla Ballestas This trip is as equally rich in geological, archaeological and cultural interest as well with visits included Matarani Arica to the Pintados Geoglphs, the Peruvian capital of Lima and the ruins of Chan Chan. There will also be the Iquique opportunity to join optional excursions to both the Atacama Desert and the Nazca Lines. Antofagasta Isla Pajaros / CHILE Isla Chanaral The Itinerary Coquimbo Valparaiso regional capital of La Serena. One are protected today as a nature Day 1 London to Santiago, Chile. Day 8 Iquique. Santiago Fly by scheduled indirect flight. of Coquimbo’s highlights is the reserve that is home to sea lion Arrive this morning picturesque Barrio Ingles. -

Technology, Disposal

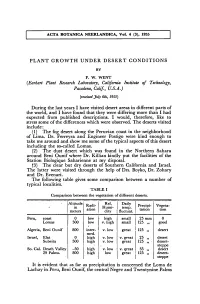

ACTA BOTANICA NEERLANDICA, Vol. 4 (3), 1955 Plant Growth under Desert Conditions BY F.W. Went (Earhart Plant Research Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif, U.S.A.) [received July 6th, 1955) the last I have visited desert in different of During years areas parts I I the world, and have found that they were differing more than had expected from published descriptions. I would, therefore, like to stress some of the differences which were observed. The deserts visited include: (1) The fog desert along the Peruvian coast in the neighborhood of Lima. Dr. Ferreyra and Engineer Postigo were kind enough to of take me around and show me some of the typical aspects this desert including the so-called Lomas. (2) The dust desert which was found in the Northern Sahara around Beni where Killian the of the Ounif Dr. kindly put facilities Station Biologique Saharienne at my disposal. (3) The clear but dry deserts of Southern California and Israel. The latter were visited through the help of Drs. Boyko, Dr. Zohary and Dr. Evenari. The following table gives some comparison between a number of typical localities. TABLE I Comparison between the vegetation of different deserts. Altitude Rel. Daily Radi- Precipi- Vegeta- in Humi- temp. ation tation tion meters dity fluctuât. Peru, coast 0 low high small 25 mm 0 Lomas 300 low v. small 125 high „ good Beni Ounif 800 in low desert ter- v. 125 Algeria, great „ med. Elat 0 low 25 desert v. v. Israel, high great „ Subeita 500 v. low 125 desert- high great „ steppe -50 low 35 desert So. -

The Contribution of Fog to the Moisture and Nutritional Supply of Arthraerua

The contribution of fog to the moisture and nutritional supply of Arthraerua leubnitziae in the central Namib Desert, Namibia Tunehafo Ruusa Gottlieb Thesis presented for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Environmental and Geographical Science University of Cape Town October 2017 Supervisors: A. Prof Frank Eckardt, Department of Environmental and Geographical Science A. Prof Michael Cramer, Department of Biological Sciences Declaration ‘I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all of the work in the dissertation (or thesis), save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own’. Tunehafo Ruusa Gottlieb, October 2017 i Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors for their time and energy in support of the successful completion of this research. Thank you for your constructive criticism and effort you put in reviewing this thesis. Frank Eckardt, thank you for all your assistance, and for communicating and contributing ideas clearly. Michael Cramer, thank you for your tremendous support and constant engagement. I am grateful for your patience as you engaged with all the challenges I brought to your attention. Thank you, Mary Seely, for the discussion that led to the development of this project and for giving me a chance to be part of the FogNet project at Gobabeb. The financial assistance from the Environmental Investment Fund of Namibia (EIF), National Commission on Research Science and Technology (NCRST), University of Cape Town and Gobabeb Research and Training Centre is greatly appreciated. I would like to thank Novald Iiyambo, for assisting me with my data collection. I could never have sampled 500 plants without all your assistance. -

Crocodylus Niloticus II/B

UNEP-WCMC technical report Review of species selected on the basis of the Analysis of the European Union annual reports to CITES 2017 (Version edited for public release) Review of species selected on the basis of the Analysis of the European Union annual reports to CITES 2017. Prepared for The European Commission, Directorate General Environment, Directorate F - Global Sustainable Development, Unit F3 - Multilateral Environmental Cooperation, Brussels, Belgium. Published June 2019 Copyright European Commission 2019 Citation UNEP-WCMC. 2019. Review of species selected on the basis of the Analysis of the European Union annual reports to CITES 2017. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge. The UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment centre of the UN Environment, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in operation for over 35 years, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. Reuse of any figures is subject to permission from the original rights holders. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from UN Environment. Applications for permission, with a statement of purpose and extent of reproduction, should be sent to the Director, UNEP-WCMC, 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK. The contents of this report do -

Rodent Middens Reveal Episodic, Longdistance Plant Colonizations

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2012) 39, 510–525 ORIGINAL Rodent middens reveal episodic, long- ARTICLE distance plant colonizations across the hyperarid Atacama Desert over the last 34,000 years Francisca P. Dı´az1,2, Claudio Latorre1,2*, Antonio Maldonado3,4, Jay Quade5 and Julio L. Betancourt6 1Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology and ABSTRACT Biodiversity (CASEB) and Departamento de Aim To document the impact of late Quaternary pluvial events on plant Ecologı´a, Pontificia Universidad Cato´lica de Chile, Alameda 340, Santiago, Chile, 2Institute movements between the coast and the Andes across the Atacama Desert, northern of Ecology and Biodiversity (IEB), Las Chile. Palmeras 3425, N˜ un˜oa, Santiago, Chile, Location Sites are located along the lower and upper fringes of absolute desert 3 Laboratorio de Paleoambientes, Centro de (1100–2800 m a.s.l.), between the western slope of the Andes and the Coastal ´ Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Aridas Ranges of northern Chile (24–26° S). (CEAZA), Colina del Pino s/n, La Serena, Chile, 4Direccio´n de Investigacio´n, Universidad Methods We collected and individually radiocarbon dated 21 rodent middens. de La Serena, Benavente 980, La Serena, Chile, Plant macrofossils (fruits, seeds, flowers and leaves) were identified and pollen 5Department of Geosciences, University of content analysed. Midden assemblages afford brief snapshots of local plant Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, 6US Geological communities that existed within the rodents’ limited foraging range during the Survey, Tucson, AZ, USA several years to decades that it took the midden to accumulate. These assemblages were then compared with modern floras to determine the presence of extralocal species and species provenance. -

Microclimatic Conditions and Water Content Fluctuations Experienced By

Biogeosciences, 17, 5399–5416, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-5399-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Microclimatic conditions and water content fluctuations experienced by epiphytic bryophytes in an Amazonian rain forest Nina Löbs1, David Walter1,2, Cybelli G. G. Barbosa1, Sebastian Brill1, Rodrigo P. Alves1, Gabriela R. Cerqueira3, Marta de Oliveira Sá3, Alessandro C. de Araújo4, Leonardo R. de Oliveira3, Florian Ditas1,a, Daniel Moran-Zuloaga1, Ana Paula Pires Florentino1, Stefan Wolff1, Ricardo H. M. Godoi5, Jürgen Kesselmeier1, Sylvia Mota de Oliveira6, Meinrat O. Andreae1,7, Christopher Pöhlker1, and Bettina Weber1,8 1Multiphase Chemistry and Biogeochemistry Departments, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, 55128 Mainz, Germany 2Biogeochemical Process Department, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, 07701 Jena, Germany 3Large Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in Amazonia (LBA), Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia (INPA), Manaus-AM, CEP 69067-375, Brazil 4Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA), Belém-PA, CEP 66095-100, Brazil 5Environmental Engineering Department, Federal University of Parana, Curitiba, PR, Brazil 6Biodiversity Discovery Group, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, 2333 Leiden, CR, the Netherlands 7Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA 8Institute for Biology, Division of Plant Sciences, University of Graz, 8010 Graz, Austria anow at: Hessisches Landesamt für Naturschutz, -

Transfrontier Ecosystems and Internationally Adjoining Protected Areas 1

Transfrontier Ecosystems and Internationally Adjoining Protected Areas © 1999 - Dorothy C. Zbicz, Ph.D. - Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment, Box 90328, Durham, NC 27511, USA 1. The “Nature” of Boundaries Nature rarely notices political boundaries. Most of the arbitrarily-drawn political boundaries dividing the Earth into countries were delineated as a result of wars or political compromises, often by geographers never even having set eyes on the land. As a result, these political divisions frequently have severed functioning ecosystems. Although neither animals nor plants recognize these arbitrary boundaries, the fact that humans do often threatens the continued survival of the other species and the ecosystems. As conservation biologists have begun to emphasize the importance of larger-scale ecosystem-based management and regional approaches to biodiversity conservation, political boundaries dividing ecosystems have become even more problematic. For the past 120 years, protected natural areas have been the traditional means of nature conservation. Today these areas encompass approximately 13.2 million square kilometers around the world (Green and Paine 1998). For various reasons, many of these protected areas exist on international boundaries, and many of these suggest the existence of transfrontier ecosystems. These are especially likely where protected areas in different countries adjoin across international boundaries. This paper contains an updated Global List of Adjoining Protected Areas (as of early 1999), referred to earlier as “transfrontier protected areas complexes”1, (Zbicz and Green 1997a) (Zbicz and Green 1997b). Although continually evolving, this list provides a glimpse of the extent of the problem of internationally divided ecosystems and the need for improved transfrontier cooperation 2. -

Water Availability, Protected Areas, and Natural Resources in The

MOUNTAINRESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT,VOL. 17, No. 3, 1997, PP. 229-238 WATERAVAILABILITY, PROTECTED AREAS, AND NATURAL RESOURCES INTHE ANDEAN DESERT ALTIPLANO BRUNO MESSERLI, MARTIN GROSJEAN, AND MATHIAS VUILLE Institute of Geography Universityof Berne, Hallerstrasse12 CH-3012 Berne, Switzerland ABSTRACTThe arid Andes between 18? and 30? South are located in the transition zone between the tropical and westerly circulation belts. Precipitation rates are lower than 150-200 mm/yr. Resultsfrom paleoclimatic and isotope hydrologic research suggest that modern recharge of the water resources in this area is very limited, or even below the level of detection. The groundwater resources of today were formed when precipitation rates were greater than at present by a factor of 2.5. Thus, water is a resource that is renewed extremely slowly,or is even non-renewable. The distribution of mountain protected areas along the 7,500 km Andean Cordilleraand the extent of the arid diagonal, the zone of extremely low precipitation that crosses from the western flank in southern Ecuador and Peru to the eastern flank in Argentina, are compared. This indicates the very low density of protected areas within the arid diagonal and the potential for endangerment of diversity in this highly sensitive, dynamic, and harsh environment. Scientific knowledge about the age and origin of water resourcesand maps of water protection zones are the basic elements required for decision making. This type of information should help to resolve the growing conflict between the users of water, especially between the expanding mining industry,conservationists, and local communities concerned with the integrity of the fragile mountain ecosystems.