This File Has Been Cleaned of Potential Threats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passive Water Collection with the Integument: Mechanisms and Their Biomimetic Potential (Doi:10.1242/ Jeb.153130) Philipp Comanns

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb185694. doi:10.1242/jeb.185694 CORRECTION Correction: Passive water collection with the integument: mechanisms and their biomimetic potential (doi:10.1242/ jeb.153130) Philipp Comanns There was an error published in J. Exp. Biol. (2018) 221, jeb153130 (doi:10.1242/jeb.153130). The corresponding author’s email address was incorrect. It should be [email protected]. This has been corrected in the online full-text and PDF versions. We apologise to authors and readers for any inconvenience this may have caused. Journal of Experimental Biology 1 © 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb153130. doi:10.1242/jeb.153130 REVIEW Passive water collection with the integument: mechanisms and their biomimetic potential Philipp Comanns* ABSTRACT 2002). Furthermore, there are also infrequent rain falls that must be Several mechanisms of water acquisition have evolved in animals considered (Comanns et al., 2016a). living in arid habitats to cope with limited water supply. They enable Maintaining a water balance in xeric habitats (see Glossary) often access to water sources such as rain, dew, thermally facilitated requires significant reduction of cutaneous water loss. Reptiles condensation on the skin, fog, or moisture from a damp substrate. commonly have an almost water-proof skin owing to integumental This Review describes how a significant number of animals – in lipids, amongst other components (Hadley, 1989). In some snakes, excess of 39 species from 24 genera – have acquired the ability to for example, the chemical removal of lipids has been shown to – passively collect water with their integument. -

Why Does the Namib Desert Tenebrionid Onymacris Unguicularis (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Fog-Bask?

Eur. J. Entomol. 105: 829–838, 2008 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1404 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Why does the Namib Desert tenebrionid Onymacris unguicularis (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) fog-bask? STRINIVASAN G. NAIDU Department of Physiology, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 719 Umbilo Road, Durban 4041, South Africa; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Water balance, osmoregulation, lipid, glycerol, Tenebrionidae, Onymacris unguicularis, Namib Desert Abstract. Dehydration of Onymacris unguicularis (Haag) for 10 days at 27°C resulted in a weight loss of 14.9%, and a 37% decrease in haemolymph volume. Although there was an overall decrease in the lipid content during this period, metabolic water production was insufficient to maintain total body water (TBW). Rehydration resulted in increases in body weight (6.2% of initial weight), TBW (to normality), and haemolymph volume (sub-normal at the end of rehydration). Despite an increase of 44.0 mg in the wet weight of O. unguicularis after drinking for 1h, there was little change in the water content at this time, although the total lipid content increased significantly. Increases in haemolymph osmolality, sodium, potassium, chloride, amino acid and total sugar con- centrations during dehydration were subject to osmoregulatory control. No evidence of an active amino acid-soluble protein inter- change was noted during dehydration or rehydration. Haemolymph trehalose levels were significantly increased at the end of rehydration (relative to immediate pre-rehydration values), indicating de novo sugar synthesis at this time. Osmotic and ionic regula- tion was evident during rehydration, but control of OP during haemolymph-dilution is poor and accomplished largely by the addition to the haemolymph of free amino acids and solute(s) not measured in this study. -

Price List 2018

SA VENOM SUPPLIERS – PRICE LIST 2018 SNAKE VENOM N.B Certificate of origin available on request at $50.00 per certificate. Anti-snake bite serum prices available on request. Polyvalent for most African snakes, monovalent for Echis and Boomslang. SPECIES KNOWN AS US$ PRICE PER GRAM Aspidelaps scutatus Shield Nose Snake 2016.00 Atheris Chloreschis Bush Viper 2100.00 Atheris Nitschei Great Lakes Bush Viper 1848.00 Bitis arietans Puff Adder 202.00 Bitis caudalis Horned Adder 1680.00 Bitis gabonica Gaboon Adder 235.00 Bitis nasicornis Rhino Viper 235.00 Bitis rhinoceros West African Gaboon Adder 235.00 Bothrops Atrox Fer-Der-Lance 700.00 Causus rhombeatus Night Adder 258.00 Cerastes Cerastes Horned Viper 812.00 Dendroaspis angusticeps Green Mamba 571.00 Dendroaspis polylepis Black Mamba 554.00 Dendroaspis jamesoni Jameson's Mamba 952.00 Dendroaspis viridis West African Green Mamba 728.00 Dispholidus typus Boomslang 4800.00 Echis Leucogaster White-bellied Carpet Viper 4368.00 Echis Pyramidium North East Carpet Viper 3640.00 Echis Ocellatus West African Carpet Viper 3752.00 Echis Coloratus Painted Carpet Viper 3808.00 Hemachatus Haemachatus Rinkhals 414.00 Naja annulifera Snouted Cobra 392.00 Naja Kaouthia Kaouthia Monocle Cobra 280.00 Naja melanoleuca Forest Cobra 392.00 [email protected] | [email protected] www.venomsa.com Naja pallida Red spitting Cobra 235.00 Naja mossambica Mozambique Spitting Cobra 336.00 Naja Nubiae Nubian Spitting Cobra 235.00 Naja Nivea Cape Cobra 476.00 Naja Haje Haje Egyptian Cobra 392.00 Naja Nigricollis Black-necked Spitting Cobra 336.00 Proatheris Superciliaris Swamp Viper 2240.00 Pseudocerastes Persicus Spider Tail Horned Viper 874.00 Rhamphiophis Rostratus Rufous Beaked Snake 2240.00 Trimerusurus Okinawnesis Okinawa Habu 280.00 Walterinnesia Aegyptia Black Desert Cobra 1400.00 SCORPION VENOM N.B Certificate of origin available on request at $50.00 per certificate. -

Early German Herpetological Observations and Explorations in Southern Africa, with Special Reference to the Zoological Museum of Berlin

Bonner zoologische Beiträge Band 52 (2003) Heft 3/4 Seiten 193–214 Bonn, November 2004 Early German Herpetological Observations and Explorations in Southern Africa, With Special Reference to the Zoological Museum of Berlin Aaron M. BAUER Department of Biology, Villanova University, Villanova, Pennsylvania, USA Abstract. The earliest herpetological records made by Germans in southern Africa were casual observations of common species around Cape Town made by employees of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) during the mid- to late Seven- teenth Century. Most of these records were merely brief descriptions or lists of common names, but detailed illustrations of many reptiles were executed by two German illustrators in the employ of the VOC, Heinrich CLAUDIUS and Johannes SCHUMACHER. CLAUDIUS, who accompanied Simon VAN DER STEL to Namaqualand in 1685, left an especially impor- tant body of herpetological illustrations which are here listed and identified to species. One of the last Germans to work for the Dutch in South Africa was Martin Hinrich Carl LICHTENSTEIN who served as a physician and tutor to the last Dutch governor of the Cape from 1802 to 1806. Although he did not collect any herpetological specimens himself, LICHTENSTEIN, who became the director of the Zoological Museum in Berlin in 1813, influenced many subsequent workers to undertake employment and/or expeditions in southern Africa. Among the early collectors were Karl BERGIUS and Ludwig KREBS. Both collected material that is still extant in the Berlin collection today, including a small number of reptile types. Because of LICHTENSTEIN’S emphasis on specimens as items for sale to other museums rather than as subjects for study, many species first collected by KREBS were only described much later on the basis of material ob- tained by other, mostly British, collectors. -

Instituto Tecnológico Y De Estudios Superiores De Monterrey

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Campus Monterrey School of Engineering and Sciences DESARROLLANDO UNA SUPERFICIE QUE PROPICIA LA CONDENSACION PARA COSECHAR AGUA DEL MEDIO AMBIENTE AL TRATAR UNA TEJA DE ARCILLA CON NANOPARTICULAS DE SiO2-OTS DEVELOPING A SURFACE WITH DEW ENHANCING PROPERTIES TO HARVEST WATER FROM THE ENVIRONMENT BY TREATING A CLAY SUBSTRATE WITH SiO2-OTS NANOPARTICLES By Leonardo Arturo Beneditt Jimenez A00809139 Submitted to the School of Engineering and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Nanotechnology Monterrey Nuevo León, May 30th, 2019 2 FORMATO DE DECLARACIÓN DE ACUERDO PARA USO DE OBRA Por medio del presente escrito, Leonardo Arturo Beneditt Jiménez (en lo sucesivo EL AUTOR) hace constar que es titular intelectual de la obra titulada DEVELOPING A SURFACE WITH DEW ENHANCING PROPERTIES TO HARVEST WATER FROM THE ENVIRONMENT BY TREATING A CLAY SUBSTRATE WITH SiO2- OTS NANOPARTICLES (en lo sucesivo LA OBRA), en virtud de lo cual autoriza al Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (en lo sucesivo el ITESM) para que efectúe resguardo mediante copia digital o impresa para asegurar su conservación, preservación, accesibilidad, disponibilidad, visibilidad, divulgación, distribución, transmisión, reproducción y/o comunicación pública con fines académicos o propios al objeto de la institución y sin fines de lucro como parte del Repositorio Institucional del ITESM. EL AUTOR reconoce que ha desarrollado LA OBRA en su totalidad de forma íntegra y consistente cuidando los derechos de autor y de atribución, reconociendo el trabajo intelectual de terceros. Esto incluye haber dado crédito a las contribuciones intelectuales de terceros que hayan participado como coautores, cuando los resultados corresponden a un trabajo colaborativo. -

Informe De Avance Iabin Ecosystem Grant

INFORME DE AVANCE IABIN ECOSYSTEM GRANT: DIGITALIZACIÓN DE DATOS E INFORMACIÓN, DEPURACIÓN Y ESTANDARIZACIÓN DE PISOS DE VEGETACIÓN DE CHILE Patricio Pliscoff, Federico Luebert, Corporación Taller La Era, Santiago, Chile, 30 de Septiembre de 2008. Resumen Se ha ingresado el 50,6% de la información bibliográfica recopilada para el desarrollo de la base de información puntual georeferenciada de inventarios de vegetación. Se ha depurado el 68,5% del total de pisos de vegetación de la cartografía digital. Se ha comenzado el proceso de estandarización de la clasificación de pisos de vegetación con el estándar de metadatos del IABIN, encontrando algunas dificultades en el ingreso de información. Las equivalencias entre pisos de vegetación y sistemas ecológicos ya ha sido finalizada. Abstract The 50.6% of the compiled bibliographic references for the development of the georeferenced database of vegetation inventories have been included. The 68.5% of vegetation belts of the digital cartography have been debbuged and fixed. The standarization process of vegetation belts has been begun, entering data into the IABIN ecosystem standard, finding some difficulties in the information entrance. The equivalences between vegetation belts and ecological systems has already been finished. Objetivos del Proyecto 1) Generación de una base de información puntual georeferenciada de inventarios de vegetación. 2) Depuración de cartografía digital de pisos vegetacionales. 3) Estandarizar la clasificación de Pisos de vegetación con los estándares de metadatos de IABIN y con la clasificación de Sistemas Ecológicos de NatureServe. Productos y resultados esperados De acuerdo con los objetivos mencionados, se espera obtener los siguientes resultados: - Una base de datos georeferenciada de puntos con inventarios de vegetación chilena - Una cartografía depurada de pisos de vegetación de Chile (Luebert & Pliscoff 2006) - Un esquema de equivalencias entre la clasificación de pisos de vegetación de Chile (Luebert & Pliscoff 2006) y la clasificación de sistemas ecológicos de NatureServe (2003). -

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections Environmental Conservation Law 11-0103. Definitions. As used in the Fish and Wildlife Law: 1. a. "Fish" means all varieties of the super-class Pisces. b. "Food fish" means all species of edible fish and squid (cephalopoda). c. "Migratory fish of the sea" means both catadromous and anadromous species of fish which live a part of their life span in salt water streams and oceans. d. "Fish protected by law" means fish protected, by law or by regulations of the department, by restrictions on open seasons or on size of fish that may be taken. e. Unless otherwise indicated, "Trout" includes brook trout, brown trout, red-throat trout, rainbow trout and splake. "Trout", "landlocked salmon", "black bass", "pickerel", "pike", and "walleye" mean respectively, the fish or groups of fish identified by those names, with or without one or more other common names of fish belonging to the group. "Pacific salmon" means coho salmon, chinook salmon and pink salmon. 2. "Game" is classified as (a) game birds; (b) big game; (c) small game. a. "Game birds" are classified as (1) migratory game birds and (2) upland game birds. (1) "Migratory game birds" means the Anatidae or waterfowl, commonly known as geese, brant, swans and river and sea ducks; the Rallidae, commonly known as rails, American coots, mud hens and gallinules; the Limicolae or shorebirds, commonly known as woodcock, snipe, plover, surfbirds, sandpipers, tattlers and curlews; the Corvidae, commonly known as jays, crows and magpies. (2) "Upland game birds" (Gallinae) means wild turkeys, grouse, pheasant, Hungarian or European gray-legged partridge and quail. -

Long-Term Population Dynamics of Namib Desert Tenebrionid Beetles Reveal Complex Relationships to Pulse-Reserve Conditions

insects Article Long-Term Population Dynamics of Namib Desert Tenebrionid Beetles Reveal Complex Relationships to Pulse-Reserve Conditions Joh R. Henschel 1,2,3 1 South African Environmental Observation Network, P.O. Box 110040 Hadison Park, Kimberley 8301, South Africa; [email protected] 2 Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State, P.O. Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa 3 Gobabeb Namib Research Institute, P.O. Box 953, Walvis Bay 13103, Namibia Simple Summary: Rain seldom falls in the extremely arid Namib Desert in Namibia, but when a certain amount falls, it causes seeds to germinate, grass to grow and seed, dry, and turn to litter that gradually decomposes over the years. It is thought that such periodic flushes and gradual decay are fundamental to the functioning of the animal populations of deserts. This notion was tested with litter-consuming darkling beetles, of which many species occur in the Namib. Beetles were trapped in buckets buried at ground level, identified, counted, and released. The numbers of most species changed with the quantity of litter, but some mainly fed on green grass and disappeared when this dried, while other species depended on the availability of moisture during winter. Several species required unusually heavy rainfalls to gradually increase their populations, while others the opposite, declining when wet, thriving when dry. All 26 beetle species experienced periods when their numbers were extremely low, but all Citation: Henschel, J.R. Long-Term had the capacity for a few remaining individuals to repopulate the area in good times. The remarkably Population Dynamics of Namib different relationships of these beetles to common resources, litter, and moisture, explain how so many Desert Tenebrionid Beetles Reveal species can exist side by side in such a dry environment. -

Biolphilately Vol-64 No-3

Vol. 67 (1) Biophilately March 2018 5 FOG-COLLECTING BEETLES OF THE NAMIB DESERT Donald Wright, BU243 There exists in the Namib Desert of southwest Africa a group of beetles that collects moisture from the fog-laden air blowing in from the Atlantic coast. These all belong to the Family Tenebrionidae, Subfamily Pimeliinae. Those found on stamps to date include the following: Saucer Trench Beetle, Lepidochora discoidalis Gebien (Lepidochara of some) Namibia, Sc#1249c, 22 September 2012, $5.80 Onymacris paiva Haag Comoro Islands, unlisted, 28 July 2011, 2500fr SS (LR margin) (Stamperija) Fog-basking or Fog-drinking Beetle, Onymacris unguicularis Haag Comoro Islands, Sc#1078, 2 March 2009, 3000fr SS (L margin) Mozambique, Sc#1919, 30 November 2009, 175m SS (MR margin) Namibia, Sc#967a, 22 May 2000, $2 Namibia, Sc#1109, 15 February 2007, “Standard Mail” ($1.90) (with Web-footed Gecko) (perf 14×13¼) Namibia, Sc#1109a, 2008, “Standard Mail” ($1.90) (same, perf 14) Namibia, Sc#1168, 1 October 2008, “Registered Mail” ($18.20) (with False Ink Cap mushroom) Namibia, Sc#1186f, 8 February 2010, “Postcard Rate” ($4.60) Namibia, unlisted, 2010, “Standard Mail” ($2.50) (design similar to Sc#1186f) Long-legged White Namib Beetle, Stenocara eburnea Pascoe Niger, Sc#1054a, 27 July 2000, 200fr Namib Desert Beetle, Stenocara gracilipes Solier Kenya, Sc#854y, 16 November 2011, 65sh These are flightless beetles, many with fused wing covers (elytra). They are diurnal, burying themselves in their sandy habitat at night, and emerging during the day. There are 21 species of Onymacris, four of Stenocara, three of Lepidochora, and four of Physasterna. -

Technology, Disposal

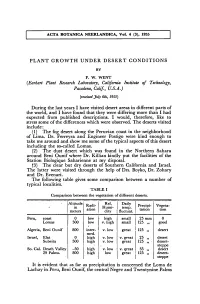

ACTA BOTANICA NEERLANDICA, Vol. 4 (3), 1955 Plant Growth under Desert Conditions BY F.W. Went (Earhart Plant Research Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif, U.S.A.) [received July 6th, 1955) the last I have visited desert in different of During years areas parts I I the world, and have found that they were differing more than had expected from published descriptions. I would, therefore, like to stress some of the differences which were observed. The deserts visited include: (1) The fog desert along the Peruvian coast in the neighborhood of Lima. Dr. Ferreyra and Engineer Postigo were kind enough to of take me around and show me some of the typical aspects this desert including the so-called Lomas. (2) The dust desert which was found in the Northern Sahara around Beni where Killian the of the Ounif Dr. kindly put facilities Station Biologique Saharienne at my disposal. (3) The clear but dry deserts of Southern California and Israel. The latter were visited through the help of Drs. Boyko, Dr. Zohary and Dr. Evenari. The following table gives some comparison between a number of typical localities. TABLE I Comparison between the vegetation of different deserts. Altitude Rel. Daily Radi- Precipi- Vegeta- in Humi- temp. ation tation tion meters dity fluctuât. Peru, coast 0 low high small 25 mm 0 Lomas 300 low v. small 125 high „ good Beni Ounif 800 in low desert ter- v. 125 Algeria, great „ med. Elat 0 low 25 desert v. v. Israel, high great „ Subeita 500 v. low 125 desert- high great „ steppe -50 low 35 desert So. -

The Contribution of Fog to the Moisture and Nutritional Supply of Arthraerua

The contribution of fog to the moisture and nutritional supply of Arthraerua leubnitziae in the central Namib Desert, Namibia Tunehafo Ruusa Gottlieb Thesis presented for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Environmental and Geographical Science University of Cape Town October 2017 Supervisors: A. Prof Frank Eckardt, Department of Environmental and Geographical Science A. Prof Michael Cramer, Department of Biological Sciences Declaration ‘I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all of the work in the dissertation (or thesis), save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own’. Tunehafo Ruusa Gottlieb, October 2017 i Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors for their time and energy in support of the successful completion of this research. Thank you for your constructive criticism and effort you put in reviewing this thesis. Frank Eckardt, thank you for all your assistance, and for communicating and contributing ideas clearly. Michael Cramer, thank you for your tremendous support and constant engagement. I am grateful for your patience as you engaged with all the challenges I brought to your attention. Thank you, Mary Seely, for the discussion that led to the development of this project and for giving me a chance to be part of the FogNet project at Gobabeb. The financial assistance from the Environmental Investment Fund of Namibia (EIF), National Commission on Research Science and Technology (NCRST), University of Cape Town and Gobabeb Research and Training Centre is greatly appreciated. I would like to thank Novald Iiyambo, for assisting me with my data collection. I could never have sampled 500 plants without all your assistance. -

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals The information recorded here is essential to emergency services personnel so that they may protect themselves and your neighbors, provide for the safety of your animals, ensure the maximum protection and preservation of your property, and provide you with emergency services without unnecessary delay. Every person in New York State, who owns, possesses, or harbors a wild animal, as set forth in General Municipal Law §209-cc, must file this Report annually, on or before April 1, of each year, with the clerk of the city, village or town (if outside a village) where the animal is kept. A list of the common names of animals to be reported is enclosed with this form. Failure to file as required will subject you to penalties under law. A separate Report is required to be filed annually for each address where a wild animal is harbored. Exemptions: Pet dealers, as defined in section 752-a of the General Business Law, zoological facilities and other exhibitors licensed pursuant to U.S. Code Title 7 Chapter 54 Sections 2132, 2133 and 2134, and licensed veterinarians in temporary possession of dangerous dogs, are not required to file this report. Instructions for completing this form: 1. Please print or type all information, using blue or black ink. 2. Fill in the information requested on this page. 3. On the continuation sheets, fill in the information requested for each type of animal that you possess. 4. Return the completed forms to the city, town, or village clerk of each municipality where the animal or animals are owned, possessed or harbored.