The Efficiency of the English Longbow a Long Standing Debate in Academia, Which Can Place the Realm and Value Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ucp013-012.Pdf

INDEX* Titles of papers in bold face. Achomawi, 264, 267, 268, 283, £92, Arrow release, 120-122, 272, 334, 388. 293, 296, 299, 301, 314, 315, 320; Arrows and bullets, comparison, 373. basketry, 272. Aselepias, 281. Achomawi language, radical elements, Ash, used for bows, 106. 3-16; verb stems, secondary, 18; Astronomy, 323. suffixes, local, 19-21; pronouns, Athabascan groups, 313, 319, 326; 25-26; phonology, 28-33. bow, 336. Acknowledgments, 69. Atsugewi, 268, 293. Acorns, storage of, 282. Atsugewi language, radical elements, lAdiantum, in basketry, 273. 3-16; suffixes, local, 20; other Adolescence ceremony, girls', 306, verb and noun suffixes, 23; phon- 311-313, 314. ology, 28-33. boys', 314. Badminton, 350, 351, 355, 357, 358. African bow, 343, 384. Balsa (tule balsa, rush raft), 267, Alaskan bow, 338, 380. 268-269. Alcatraz island, 50. Bannerman, Francis, 350. Algonkin groups, 326. Barnes, bow maker, 356. Amelanchier alnifolia (serviceberry), Barton, R. F., 390. 361. Basket, "canoe," 250; as granary, Andaman islands, bow, 343, 384. 282-283. Anderson, R. A., quoted, 42, 44, 45, Basketry, complexes, 272; character- 47, 52-53. istics of, among the tribal groups, Apache bow, 340, 382; arrow, 382. 272-275; materials and tech- Apocynum cannabinum, 281. niques, 273-275; types: bottle- Archery, rounds in: English or York, neck, 273; coiled, 250, 263, 273, 123; American, 123; English, 332, 274; twined, 263, 272-273. See 351. also under names of tribes. Archery, Yahi, 104. Basketry cap, woman 's, 262-263; cap Armor, 299, 357. and hopper, 273; leggings, 262; Arrowheads, plates showing, opp. 103, moccasin, 262; traps, 248. -

Yumi and Ya: a Brief Survey of Japanese Archery

A.S. 47 XLVII ● Fall 2013 ● Vol. I ● Issue 3 A.S. 47 XLVII ● Fall 2013 ● Vol. I ● Issue 3 THE WAY WE WERE: SCA Archery: Origins & Evolution INSIDE: SSSIIIRRR JJJOOONNN FFFIIITTTZZZ RRRAAAUUUFFF::: Profile of a Living Legend How it Began: Inga’s Tale of SCA Target & Combat Archery The First SCA Combat Arrow ALSO THIS EDITION: Meet the Archers Yumi and Ya: A brief survey of Japanese Archery Thumb Rings Fire Across the River: Tactics for Combat Archers from the Senryaku A Study of Medieval and Renaissance Arrow Shaft Sizes The Medieval Archer’s Reading List Photo by Henry Jakl Thorunn Smallwolf (Breanne Crane) of Avacal, An Tir Winner of the Quad War Bow Competition THE WAY WE WERE A.S. 47 XLVII ● Fall 2013 ● Vol. I ● Issue 3 SCA Archery: Origins & Evolution In this Fall Edition (2013) of Quivers & Quarrels, we Inside this Issue: explore the origins and evolution of target and combat Meet the Archers............................................................1-2 archery in the SCA. Sir Jon Fitz Rauf: Profile of a Living Legend ......3-5 New in this edition: Meet the Archers, featuring photos and bios of local archery stars of all ages. Also, be Yumi and Ya: A brief survey of Japanese Archery 6-11 sure to read about Sir Jon Fitz Rauf, the godfather of Warbows have come to Avacal (An Tir)!........... 12-13 SCA archery, and a regular contributor to this publication. Thumb Rings............................................................. 14-15 This is the official quarterly publication of The Archery How it Began: Inga’s Tale of SCA Target & Combat Community of the Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. -

?Wmrk Xli /Rkpmwl Psrkfs[ + Vglivw Hy 1Irizsmw

?WMRK XLI /RKPMWL PSRKFS[ + VGLIVW HY 1IRIZSMW www.toxophilus.org Security when shooting a bow Archery is a potentially dangerous sport which must only be carried out in an appropriate place reserved for such activity with correct supervision. We decline all responsibility for damage and/or accidents which occur as a result of putting any of the activities described in this tutorial into practice. Shooting line When shooting in a group, it is important that all archers remain behind (or astride in the case of a competition) a visible (or imaginary) line while arrows are being shot. Crossing the line towards the targets during shooting is not only dangerous but is sanctioned by immediate disqualification during competitions. Spectators must, under no circumstances, be allowed to stand between the archer and the target even if they are outside the shooting angle. R etrieving arrows from the target The basic rule is to wait for the last archer to shoot his or her last arrow before advancing to collect one’s own arrows from the target. However, if the order “fast” is given, all archers must immediately stop shooting. The signal that indicates that all is clear to cross the shooting line is when a designated person shouts the order: “Arrows” (or a word such as “score” or “pull”). A rm ing a bow Never arm a bow or even place (nock) the arrow onto the bowstring if the bow is not pointed at the target. All archers must be aware that an arrow can be loosed accidentally before it is correctly aimed. -

English Longbow Testing Against Various Armor Circa 1400

English Longbow Testing against various armor circa 1400 By Matheus Bane January 2006 2/28 Thesis Throughout all my research on archery and armour, one detail seems to vary from expert to ex- pert. This detail is the effectiveness of armour against archery. From one source to another, the conclusions (almost always stated as fact) are wildly different. For example, a website by the BBC states that: “In tests against a steel breastplate, a bodkin-tipped arrow would dent the armour at 260ft, puncture it at 98ft, and penetrate right through plate and underlying dou- blet coat to the flesh at 65ft.” (Channel 4) Although a seemingly trustworthy source, there is no detail given about the elements used. An- other source states; “an arrowhead, on the other hand, would only need to deliver 120 Joules to pierce the mail and padding underneath. An archer would find this difficult” (Williams) Dr Williams very clearly details all his methods and elements but fails to consider that mail is flexible and could still kill a person without penetration. This mass weapon effect has never been considered in any testing that I have come across. These type of inconsistencies have been the fuel for debate for as long as I have been in the re- search communities for archery and armour. During these debates, I have always had my own opinion but never felt qualified to interject since I could not back it up. Unfortunately, most people in these debates are stating opinion or quoting some statement by some expert that was stating an opinion. -

CMH Newsletter 7/18

COLORADO MILITARY HISTORIANS NEWSLETTER XIX, No. 7 July 2018 A Comparison between Composite and Long Bows By Larry Irons Introduction I am tired of people telling me that the Mongol composite bow is superior to all other bows just because it is a Mongol horseman using it. I am a scientist and I refuse to believe that is the reason. I want to know if it really is superior and I want to know why. I don’t believe that there is a genetic reason. I also have a prejudice against Indian longbowmen. I don’t believe that a cane bow is superior to other bows. So let’s look at the different kinds of bows and the physics of bows. We will also look at how training and experience will affect the archer’s effectiveness. I have been trained as an archer and I have interviewed some modern bow hunters to build an understanding of the methods, conditioning, and training involved in bow hunting. I believe that this information is valid in attempting to understand ancient and medieval military archery. Classification of Bows A bow can be classified by the length of the bow staff and the construction. This is the classification that I am using: 1. Self bows – A bow made of a one-piece staff of wood less than 5 feet in length. 2. Longbow - A bow made of a one-piece staff of wood more than 5 feet in length. 3. Composite bow – A bow made of more than one material approximately 4 feet in length. -

History of Archery." the Contents of This Page Were Copied from the "South African Archery Portal" (

Pre 25 A "brief history of archery." The contents of this page were copied from the "South African Archery Portal" (www.archerysa.co.za/index.htm). Pre 25,000 BC The discovery of the first stone arrowheads in Africa tends to indicate that the bow and arrow were invented there, maybe as early as 50,000 BC. It was probably developed in conjunction with the invention of the spear thrower. A short bow would be a better hunting weapon when used to stalk animals in wooded areas, rather than carry around long spears. The shape of the earliest bows can only be guessed at, as broken or worn out bows would probably end up on the cooking fire, reshaped into different tools or just thrown away. 25,000 - 18,000 BC Fire hardened points used on the arrows. Flint arrowheads shaped to a point and inserted into a slot and tied with sinew to the front of the arrow. Feathers were glued and tied with sinew to the arrow shafts. 18,000 - 9,000 BC 11,000 BC - In a burial tomb in San Teodoro Cave, Sicily, a skeleton was found with a fragment of a flint arrow head embedded in the pelvis. Arrow shafts found in Germany are dated to approx. 9,000 BC. 9,000 - 6,000 BC Bows are found in Denmark that date from approx. 8,000 - 6,000 BC. These bows are one piece made from yew or elm and are 'tillered'. (Even amount of bend on top and bottom limbs.) Tassili rock fresco depicting archer in Egypt from about 7,500 BC. -

English Longbow (Edited from Wikipedia)

English Longbow (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY The English longbow, also called the Welsh longbow, is a powerful medieval type of longbow (a tall bow for archery) about 6 feet long used by the English and Welsh for hunting and as a weapon in medieval warfare. English use of longbows was effective against the French during the Hundred Years' War, particularly at the start of the war in the battles of Sluys (1340), Crécy (1346), and Poitiers (1356), and perhaps most famously at the Battle of Agincourt (1415). They were less successful after this, with longbowmen having their lines broken at the Battle of Verneuil (1424), and being completely routed at the Battle of Patay (1429) when they were charged before they had set up their defensive position. No longbows survive from the period when the longbow was dominant (c. 1250–1450 AD), probably because bows became weaker, broke and were replaced, rather than being handed down through generations. More than 130 bows survive from the Renaissance period, however. More than 3,500 arrows and 137 whole longbows were recovered from the Mary Rose , a ship of Henry VIII's navy that sank at Portsmouth in 1545. HISTORY The origins of the English longbow are disputed. While it is hard to assess the significance of military archery in pre-Norman Conquest Anglo-Saxon warfare, it is clear that archery played a prominent role under the Normans, as the story of the Battle of Hastings shows. Their Anglo-Norman descendants also made use of military archery, as exemplified by their victory at the Battle of the Standard in 1138. -

Resolving the Longbow Puzzle

Institutionally Constrained Technology Adoption: Resolving the Longbow Puzzle Douglas W. Allen Simon Fraser University Peter T. Leeson George Mason University Abstract For over a century the longbow reigned as undisputed king of medieval Euro- pean missile weapons. Yet only England used the longbow as a mainstay in its military arsenal; France and Scotland clung to the technologically inferior cross- bow. This longbow puzzle has perplexed historians for decades. We resolve it by developing a theory of institutionally constrained technology adoption. Unlike the crossbow, the longbow was cheap and easy to make and required rulers who adopted the weapon to train large numbers of citizens in its use. These features enabled usurping nobles whose rulers adopted the longbow to potentially orga- nize effective rebellions against them. Rulers choosing between missile technol- ogies thus confronted a trade-off with respect to internal and external security. England alone in late medieval Europe was sufficiently politically stable to allow its rulers the first-best technology option. In France and Scotland political insta- bility prevailed, constraining rulers in these nations to the crossbow. The most important thing in the world, for battles, is the archers. (Philippe de Commynes, late medieval chronicler [quoted in Rog- ers 1993, p. 249]) 1. Introduction On July 19, 1333, amid the Second War of Scottish Independence, Scotland’s Sir Archibald Douglas led a massive force of some 15,000 men up Halidon Hill to face England’s King Edward III and his army of only 8,000. It was a slaughter— not of the English, but of the Scots. Edward had spread his men-at-arms in three divisions across the hilltop, flanked by archers armed with longbows. -

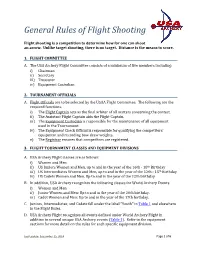

General Rules of Flight Shooting

General Rules of Flight Shooting Flight shooting is a competition to determine how far one can shoot an arrow. Unlike target shooting, there is no target. Distance is the means to score. 1. FLIGHT COMMITTEE A. The USA Archery Flight Committee consists of a minimum of five members including: i) Chairman ii) Secretary iii) Treasurer iv) Equipment Custodian 2. TOURNAMENT OFFICIALS A. Flight Officials are to be selected by the USAA Flight Committee. The following are the required functions. i) The Flight Captain acts as the final arbiter of all matters concerning the contest. ii) The Assistant Flight Captain aids the Flight Captain. iii) The Equipment Custodian is responsible for the maintenance of all equipment used in the Tournament. iv) The Equipment Check Official is responsible for qualifying the competitors’ equipment and recording bow draw weights. v) The Registrar ensures that competitors are registered. 3. FLIGHT TOURNAMENT CLASSES AND EQUIPMENT DIVISIONS A. USA Archery Flight classes are as follows: i) Women and Men ii) US Juniors Women and Men, up to and in the year of the 16th - 18th Birthday iii) US Intermediates Women and Men, up to and in the year of the 12th - 15th Birthday iv) US Cadets Women and Men, Up to and in the year of the 12th birthday B. In addition, USA Archery recognizes the following classes for World Archery Events: i) Women and Men ii) Junior Women and Men: Up to and in the year of the 20th birthday. iii) Cadet Women and Men: Up to and in the year of the 17th birthday. -

Is Not Equal to Another: a Comparative Look at Hun and Mongol Military Technologies

One Bow (or Stirrup) Is Not Equal to Another: A Comparative Look at Hun and Mongol Military Technologies Samuel Rumschlag University of Wisconsin-Madison n his landmark study of the rapid rise and de - ber of mounts which made such mobility possible cline of the Huns in the fifth century CE, E.A. (Sinor 1972: 171). Other such factors often include TIhompson observed that “history is no longer sat - nomadic battle tactics, such as the art of luring en - isfied to ascribe so striking a movement as the rise emies into vulnerable positions before attacking of the Hun empire to the genius of a single man … them (May 2018: 1), along with specific political de - it is only in terms of the development of their soci - velopments, in both nomadic polities and those of ety that we can explain … how they came to build their adversaries, that altered the nomadic balance up so vast an empire of their own, and yet proved of power vis-à-vis their opponents. While worthy unable to hold it for more than a few years” (1996: foci of scholarly attention, all these factors offer 46). By making this claim, Thompson did not in - only a partial explanation of nomadic successes. tend to diminish the role that gifted Hun leaders Scholars should also look for additional factors played in guiding their society to international that contributed to nomadic successes and can prominence—only to point out that monocausal help explain historical realities that are only par - explanations cannot adequately capture historical tially explained by appeals to leadership, mobility, reality in all its completeness. -

Asian Traditional Archery Manual

asian traditional archery manual foreword................................................................................................................................2 thumb draw...........................................................................................................................3 the mongolian draw...........................................................................................................4 the thumbring.....................................................................................................................5 wearing the ring.................................................................................................................7 making a thumb ring..........................................................................................................8 mongolian archery.............................................................................................................16 technique.........................................................................................................................17 demonstration..................................................................................................................21 chinese / manchu archery.................................................................................................30 chapter 13 of the New Book of Discipline and Effectiveness..........................................31 illustration from the Wu Bei Yao Lue................................................................................35 -

English Longbow and the Battle of Crecy

English Longbow and the Battle of Crecy On the 26th of August, in 1346, Edward III—the English King—leads his forces to a field near the French town of Crécy (in northern France). With him is his sixteen-year-old son, Edward of Woodstock (also known as The Black Prince). Although France already has a King—Philip VI—the King of England also wants to be the King of France. He has been fighting a war, against French forces, to achieve that objective. Outnumbered, Edward and his battle-weary men believe they can win this battle. How could that be possible? Because they have faith in their weapon-of-choice: the English longbow. This English weapon is no ordinary bow-and-arrow. The longbow, which the English warriors use that day at Crécy—also known as Cressy—is tall as a man. It is made from the yew tree. It requires 100 pounds of force to draw this weapon, which is also known as the Welsh Longbow. Deadly at about 200 yards, it is capable of reaching up to 320 yards. The English King orders his knights to dismount their horses. Men-on-horseback will not win the battle this day. Instead, Edward orders those knights to take their positions in a v-formation known as a "harrow." Positioning his men this way allows a greater barrage of arrows to fly against the enemy when it is time to draw the longbows. The Englishmen are not the only ones equipped with powerful bows. Opposite them are men from Genoa, helping the French.