Laetitia Nanquette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: a Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Professor Muhammad Siddiq Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2013 Abstract The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Modern Persian literary histories generally characterize the decades leading up to the Iranian Revolution of 1979 as a single episode of accumulating political anxieties in Persian poetics, as in other areas of cultural production. According to the dominant literary-historical narrative, calls for “committed poetry” (she‘r-e mota‘ahhed) grew louder over the course of the radical 1970s, crescendoed with the monarch’s ouster, and then faded shortly thereafter as the consolidation of the Islamic Republic shattered any hopes among the once-influential Iranian Left for a secular, socio-economically equitable political order. Such a narrative has proven useful for locating general trends in poetic discourses of the last five decades, but it does not account for the complex and often divergent ways in which poets and critics have reconciled their political and aesthetic commitments. This dissertation begins with the historical assumption that in Iran a question of how poetry must serve society and vice versa did in fact acquire a heightened sense of urgency sometime during the ideologically-charged years surrounding the revolution. -

Oman Embarks on New Yemen Diplomacy

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 43rd year No.13960 Monday JUNE 7, 2021 Khordad 17, 1400 Shawwal 26, 1442 Qatar calls for dialogue I know Bahrain like Tehran, Seoul expected Iran’s “Statue” tops at between Iran and back of my hand: to resume trade within VAFI & RAFI animation Arab neighbors Page 3 Dragan Skocic Page 3 3 months Page 4 festival Page 8 Candidates face each other in first televised debate Oman embarks on new TEHRAN – The first televised debates Some analysts said the debates had no among seven presidential candidates were clear winner and that candidates mostly held on Saturday afternoon. trade accusations against each other rather The hot debates took place between five than elaborate on their plans. principlist candidates - especially Saeed Hemmati was claiming that most can- See page 3 Jalili, Alireza Zakani, and Mohsen Rezaei didates were making attacks against him - with Nasser Hemmati. which was not fair. Yemen diplomacy The main contention was over an ap- A presidential candidate, Nasser Imani, proval of FATF and skyrocketing prices, said the days left to the election day are which most candidates held the central important. bank responsible for. Continued on page 2 Iran, EAEU soon to begin talks over establishing free trade zone TEHRAN - Iran and the Eurasian Economic tee, on the sidelines of the St. Petersburg Union (EAEU) are set to begin negotiations International Economic Forum. on a full-fledged joint free trade zone in “The EAEU made the appropriate de- the near future, the press service of the cisions regarding the launch of the nego- Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC) tiations in December 2020. -

'Ubayd-I Zakani's Counterhegemonic Poetics: Providing a Literary Context for the Ghazals of Hafiz

UCLA Iranian Studies The Jahangir and Eleanor Amuzegar Chair in Iranian Studies & The Musa Sabi Term Chair of Iranian Studies present ‘Ubayd-i Zakani’s Counterhegemonic Poetics: Providing a Literary Context for the Ghazals of Hafiz Dominic Parviz Brookshaw University of Oxford Friday, February 12, 2016 | 11348 Charles E. Young Research Library | 4:00pm For far too long, the ghazals (short lyric poems) of Hafiz (d. ca 1390) have been discussed in isolation from those of his contemporaries. Although Hafiz was without doubt the most significant poet active in mid- to late fourteenth-century Shiraz, he was not the only poet attached to the Injuid and Muzaffarid courts to produce ghazals of elegance and complexity. Some scholars of Hafiz are now beginning to practise what could be called “lateral literary analysis” and are examining Hafiz’s poems in tandem with those of his competitors with whom he engaged in poetic dialogue and alongside whom he vied to secure the favour of the rulers of Fars. In this talk I will show, through the detailed analysis of quasi-companion poems penned by Hafiz and the slightly more senior ‘Ubayd-i Zakani (d. 1371), how our understanding of the semantic depth of Hafiz’s ghazals can be augmented. The ghazals of ‘Ubayd, who is chiefly celebrated for his satirical works, provide a fruitful point for comparison with those of Hafiz because of their often irreverent tone. It will be argued that what might appear to be irreverence on ‘Ubayd’s part is in fact a deliberate counterhegemonic poetic agenda, one he used to upset the aesthetic status quo embodied in the verses of his chief rival, Hafiz. -

Hosseini, Mahrokhsadat.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Iranian Women’s Poetry from the Constitutional Revolution to the Post-Revolution by Mahrokhsadat Hosseini Submitted for Examination for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies University of Sussex November 2017 2 Submission Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Mahrokhsadat Hosseini Signature: . Date: . 3 University of Sussex Mahrokhsadat Hosseini For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies Iranian Women’s Poetry from the Constitutional Revolution to the Post- Revolution Summary This thesis challenges the silenced voices of women in the Iranian written literary tradition and proposes a fresh evaluation of contemporary Iranian women’s poetry. Because the presence of female poets in Iranian literature is a relatively recent phenomenon, there are few published studies describing and analysing Iranian women’s poetry; most of the critical studies that do exist were completed in the last three decades after the Revolution in 1979. -

FORUGH FARROKHZAD O Bejeweled Realm…

!"#$%&#!'( )* S+,&'+ W,&-. FORUGH FARROKHZAD O Bejeweled Realm… Victory! Got myself registered. Decorated an ID card with my name and face, and my existence took on a number. So, long live number 678, precinct 5, Tehran. No more worries, now I can relax in my motherland’s bosom, suckle on our past glory, lulled by lullabies of progress and culture and the jingle jangle of the laws’ rattle. Ah yes, no more worries… In excitement I go to the window, breathe in 678 lungs-full of air smelling of shit, garbage, and piss, and under 678 IOUs and job applications I sign my name: Forugh Farrokhzad. What a blessing to live in the land of poetry, roses, and nightingales when one’s existence is at last noted; a land where from behind the curtains my /rst registered glimpse spies 678 poets— scoundrels who in the guise of eccentric bums scrounge about trash bins for words and rhymes; a land where the sound of my /rst o0cial footsteps 144 rouses into lazy !ight from dark swamps and into the edge of day 678 mystic nightingales who for sheer fun have transformed into old crows; a land where my "rst o#cial breath mingles with the smell of 678 roses manufactured in the grand Plasco Plastic factory. Yes, it’s a blessing to exist in the birthplace of the junkie "ddler Sheik Abu Clown, and Sheik “O-heart O-heart” Tambourine Player— vagrant son of a son of son of a tambourine player— in the city of superstar portly legs, hips, and breasts plastered on the covers of ART; in the cradle of the espousers of “Let it be, what has it to do with me?” and of Olympic-style intelligence competitions where on every media channel new prodigies blow their own horns. -

Alumni Literary Journal of the BU Creative Writing Program

236 Alumni Literary Journal of the BU Creative Writing Program Issue 3 Fall 2011 Editor Caroline Woods Poetry Editor Bekah Stout Contributing Faculty Robert Pinsky Program Director Leslie Epstein Cover Design Zachary Bos TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Note 3 Fiction: ILLEGAL DREAMS 6 J. Kevin Shushtari Poetry: THE WANT BONE; THE WAVE; ANTIQUE 16 Robert Pinsky Fiction: THE GIRL FROM HIGHWATER 18 Swann Li Poetry: KRISTALLNACHT 33 Martin Edmunds Fiction: ADMISSION 34 Kathleen Carr Foster Poetry and Prose: THREE TRANSLATIONS 57 Ani Gjika Poetry: TO A PHILOSOPHER 64 Zachary Bos Fiction: A TEMPORARY FIX 65 Joseph Fazio Poetry: TWO UNGARETTI TRANSLATIONS 69 Dan Stone Non-fiction: ANNE SEXTON “ONE WRITES BECAUSE ONE HAS TO” 71 (EXCERPT) Mary Baures Fiction: A RIVER CANNOT BE A RIVER 74 Shilpi Suneja EDITORS’ NOTE Thank you for reading Issue 3 of 236, the Alumni Literary Journal of the BU Creative Writing MFA Program. 236 is an online publication that appears twice yearly, in the fall and spring. We publish exclusively the work of our alumni, with one faculty contributor in each issue. This fall we’re excited to include three poems by our esteemed poetry professor Robert Pinsky. You’ll notice that many of the stories and poems in this issue already appeared in notable journals on the web and in print, and many are award-winners. We are equally excited to include first-time publications in our pages. If you graduated from our program, we’d love to hear from you. Please see the submission guidelines on the 236 homepage, and be sure to send us your updates for the program website’s News page. -

Women's Self-Definition Through Poetry

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual MadRush Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2020 Women's Self-Definition Through Poetry Olivia Samimy Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Samimy, Olivia, "Women's Self-Definition Through Poetry" (2020). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2020/poetry/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOMEN’S SELF- DEFINITION THROUGH POETRY By: Olivia Samimy Samimy 1 I. Introduction and Context The roots of this project have been growing throughout the course of all the literature classes I have taken thus far in college. I have always had a particular interest in female poets and how the barriers to women writing affected the work produced by women who were able to overcome these challenges. In my British Literature class freshman year, I learned about Aphra Behn, a woman writing in the 17th century. She was frequently criticized for being lewd; a critique I did not fully understand at the time, because she was criticized for things that I saw excused in her male contemporaries. The following year, I learned of Anne Bradstreet, a Puritan poet from America. -

Love and Pomegranates

Love and Pomegranates Love and Pomegranates Artists and Wayfarers on Iran Edited by Meghan Nuttall Sayres www.nortiapress.com 2321 E 4th Street, C-219 Santa Ana, CA 92705 contact @ nortiapress.com Copyright © 2013 Meghan Nuttall Sayres for selection and editorial matter; individual contributors: their contributions. All rights reserved by the publisher, including the right to copy, print, reproduce or distribute this book or portions thereof not covered under Fair Use. For rights information please contact the publisher. Cover photograph by Aphrodite Désirée Navab Cover design by Gaelen Sayres Text design by Russ Davis at Gray Dog Press (www.graydogpress.com) ISBN: 978-0-9848359-9-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956356 Printed in the United States of America For Manda Jahan To Iranians Everywhere With Special Thanks To Brian H. Appleton v A Note about the Text and Persian Words You will find a square at the end of several of the essays, poems, etc. This indicates that the author has provided additional material related to the piece, which is featured at the back of the book under Notes. In most cases we chose the phonetic spellings for the Persian words; however, for several names we chose common transliterations instead, such as Hafiz and Rumi. vi Table of Contents Preface p.xv Introduction p.1 First Impressions and Persian Hospitality p.7 Contributors from East and West share stories about random acts of kindness they re- ceived in Iran and the people who went out of their way to help them. Their experiences speak of encounters with those who offered them assistance, guidance, and even mentor- ing. -

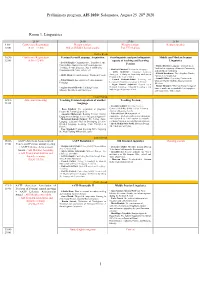

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Plenary session: Plenary session: Keynote speaker 10:00 (8:30 – 12:00) Old and Middle Iranian studies Iran-EU relations Coffee break 10:30- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 12:00 (8:30 – 12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Persian in the United States - Jamal J. Elias: Preserving Persian in the - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language Ottoman World: Shahidi, Anqaravi and the learning the formulaic language in Persian Pedagogy Mevlevis - Negar Davari Ardakani: Persian as a - Rainer Brunner: Who was Franz Steingass? National Language, Minority Languages and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Some remarks on a remarkable lexicographer Multilingual Education in Iran Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges of Persian in the 19th century -

ASSOCIATION for IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن ایران پژوهی AIS Newsletter | Volume 41, Number 2 | October 2020

ASSOCIATION FOR IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن ایران پژوهی http://associationforiranianstudies.org AIS Newsletter | Volume 41, Number 2 | October 2020 PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS This has been an eventful year for the Association for Iranian Studies. We conducted our first ever virtual workshop in August and September. We were able to offer this virtual workshop for free because the net costs of administering it turned out to be relatively low and partially offset by the addition of a new institutional member. The relatively low cost was also important because we were able to preserve resources for our long-awaited conference at the University of Salamanca. Although participation was optional, the AIS 2020 Virtual Workshop had 122 participants and featured about 40 papers and presentations. Looking forward, we may want to consider virtual workshops to facilitate more frequent scholarly interaction between biennial conferences and/or as a way to reduce the economic threshold for participation in our biennial conferences by adding a more robust simultaneous virtual component. For the foreseeable future, however, we still have to think about how best to advance the AIS mission despite an ongoing pandemic. When we cancelled AIS 2020 in March due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we hoped to reschedule for 2021. Continuing pandemic conditions have made holding our conference in 2021 impractical. Therefore, AIS Council, on the recommendation of AIS Executive Committee, has decided to hold the AIS conference in Salamanca in 2022. Those who registered for AIS 2020 will have their registrations honored for AIS 2022 so long as their membership dues are up-to-date. -

Copyright by Dylan Olivia Oehler-Stricklin 2005

Copyright by Dylan Olivia Oehler-Stricklin 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Dylan Olivia Oehler-Stricklin certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘And This is I:’ The Power of the Individual in the Poetry of Forugh Farrokhzâd Committee: Michael C. Hillmann, Supervisor M.R. Ghanoonparvar Walid Hamarneh Barbara Harlow Gail Minault ‘And This I:’ The Power of the Individual in the Poetry of Forugh Farrokhzâd by Dylan Olivia Oehler-Stricklin, B.A.; M.A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2005 Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means, Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea. —Dylan Thomas For Robin, my brother singing now unchained— here it is. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Michael Hillmann, for his academic guidance since 1988 and his insights on this dissertation. Said dissertation would not have been possible if it hadn’t been for the support of my family: my mother- in-law, Margie Stricklin, who took over my household in the final stages of writing, my mother, Louise Oehler, who made the idea realistic, and my husband, Shawn Stricklin, who helped me remember that I could. v ‘And This is I:’ The Power of the Individual in the Poetry of Forugh Farrokhzâd Publication No. _______ Dylan Olivia Oehler-Stricklin, Ph.D. -

1 KAMRAN TALATTOF Curriculum Vitae (Somewhat Abbreviated)

KAMRAN TALATTOF Curriculum Vitae (Somewhat abbreviated) 845 N Park Av, 440, Tucson AZ 85721, (520) 621-2330, [email protected] Websites: https://persian.arizona.edu, https://menas.arizona.edu/user/kamran-talattof, http://gws.arizona.edu/talattof. CURRENT POSITIONS AND TITLES (University of Arizona) o Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Chair in Persian and Iranian Studies o School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies, Professor of Near Eastern Studies o Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies, Founding Chair o Persian Program, MENAS, Founding Director o Department of Gender & Women's Studies, Affiliated/Teaching Faculty o Graduate Program in Second Language Acquisition & Teaching, Affiliated o Honors College, Faculty Advisory Committee, Member EDUCATION o Ph.D. in Near Eastern Studies, Department of Near Eastern Studies (History of Persian and Middle Eastern Literary Movements), The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1996. Dissertation published as The Politics of Writing in Iran: A History of Modern Persian Literature (in comparison with Arabic and Turkish Literature). o M.A. in Comparative Literature (Literary and Cultural Theory), Program in Comparative Literature, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1994. o Diploma in French Studies, Centre Madou, Brussels, Belgium, 1986. o M.S. Education, Minors Sociology, Political Science, Texas A & M Univ., Kingsville, 1978. o B.A. in Public Administration and Law, University of Tehran, College of Law and Public Administration, 1976. EMPLOYMENT AND EXPERIENCE o 2006–present: Professor of Near Eastern Studies o 2002–2006: Associate Professor of Near Eastern Studies, UA, Dept. of Near Eastern Studies o 1999–2001: Lecturer & Assistant Professor of Near Eastern Studies, UA, Dept.