Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

Guide to the Harpo Marx Papers

Guide to the Harpo Marx papers NMAH.AC.1290 NMAH Staff Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series : Sound Recordings: Original Audio Discs, 1947, 1949, 1956...................... 2 Series : Working Box 1............................................................................................ 6 Series : Working Box 2............................................................................................ 8 Series : Working Box 3.......................................................................................... 11 Series : Working Box 4.......................................................................................... 13 Series : Working Box 5.......................................................................................... 14 Series : Working Box 6.......................................................................................... 15 Harpo Marx Papers NMAH.AC.1290 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Harpo Marx Papers -

Jewish Culture Spring 2020 Welcome Table of Contents

QUENCH YOUR THIRST FOR JEWISH CULTURE SPRING 2020 WELCOME TABLE OF CONTENTS It isn’t a coincidence that Passover, the holiday that celebrates freedom, is in the Spring. That’s when flowers Welcome 2 bloom, temperatures rise, and, after a winter trapped indoors, we all get to play outside. Buying Tickets 3 So it also isn’t coincidence that freedom and playfulness are undercurrents of JArts’ Spring 2020 season. You’ll savor it through special menu items at Boston’s only Israeli restaurant week. You’ll hear it in the music of Support JArts 4 the unforgettable Argentinian musical duo who will be our Rukin Memorial artists-in-residence. You’ll be surprised and delighted with it in our new JLab series of experimental, unexpected works. And you’ll experience it through The Shape of Play, our public art installation in downtown Boston by artist Sari Carel, following our award-winning Events 6 Pathways to Freedom project. Staff, Contact Info, 20 Whether in a public art project or at a Seder, fun and play are far from frivolous. From the ancient afikomen to Sponsors today’s latest parody songs, people have always incorporated playful elements for passing stories like the Exodus story on to the next generation. Leadership 20 Nachman of Breslov declared “Freedom is the world of joy.” The connections between freedom, laughter, and play Season Calendar 23 are core to the Jewish experience. We hope you will join us this season. Laura Mandel Joey Baron Executive Director Artistic Director 2 BUYING TICKETS IS EASY ABOUT THE JEWISH ARTS COLLABORATIVE ONLINE JArts™ brings people together to explore and celebrate the diverse, world of Jewish art, culture, and creative expression. -

American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2013 "We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Samantha M., ""We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49)" (2013). Masters Theses. 162. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Long For a Home”: American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2013 To my late grandfather whose love for history and higher education continues to inspire my work. Despite having never entered a college classroom, he was, and continues to be, the greatest professor I ever had. ii Acknowledgments The seeds of this project were sown in the form of a term paper for an undergraduate course on the history and politics of the Middle East at Lynchburg College with Brian Crim. His never-ending mentorship and friendship have shaped my research interests and helped prepare me for the trials and tribulations of graduate school. -

Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction Céline Murillo and David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/39864 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.39864 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Céline Murillo and David Roche, “Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 06 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/39864 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.39864 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis... 1 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction Céline Murillo and David Roche 1 This special issue of Miranda is comprised of a selection of articles that were presented at the SERCIA conference entitled “Music & Movies: National and Transnational Perspectives,” organized by Frank Mehring (Radboud University) and Melvyn Stokes (University College London) at Radboud University, Nijmegen, in September 2014. We would like to start by thanking the organizers for a wonderful conference and the SERCIA board for entrusting us with the challenging task of editing this issue. The task was from the start a challenge because the conference confirmed that, even today, the majority of film scholars—that is those who do not have a background in music and musicology—remain cautious, if not downright inhibited, when it comes to studying music in film. -

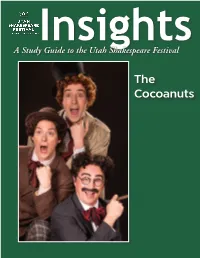

The Cocoanuts the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Cocoanuts The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the inter- pretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, publication manager and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2016, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespearean Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Tasso Feldman (above) as Harpo (Silent Red), Jim Poulos as Chico (Willie Wony Diddydony), and John Plumpis as Mr. Hammer (Groucho) in The Cocoanuts, 2016. The Cocoanuts Contents Information on the Play About the Playwright 4 Characters 7 Synopsis 7 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Marx Brothers on Broadway 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 About the Playwright: The Cocoanuts By Rachelle Hughes Almost a century ago Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright George S. Kauffman joined his creative genius with Songwriter’s Hall of Fame composer and lyricist Irving Berlin to write the Marx Brothers’ first movie and second Broadway play, The Cocoanuts. -

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection NMAH.AC.0269 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. and Wendy Shay 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1977, undated..................................................... 6 Series 2: Publications, Manuscripts, and Print Articles by Marx, 1930-1958, undated .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 3: Scripts and Sketches, 1939-1959, undated............................................. -

<Jhair^Rson Of^The Committee

CHARLIE CHAPLIN AND HARPO MARX AS MASKS OF THE COMMEDIA DELL'ARTE: THEORY AND PRACTICE by DAVID JAMES LeMASTER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved <Jhair^rson of^the Committee Accepted Dean of the Graduate School May, 1995 u ^^a- )^ O ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their help, support, and friendship. I extend a most grateful thanks to Dr. George Sorensen, whose committement to excellence reaches far beyond the classroom. Dr. Sorensen sacrificed of himself as both a reader and a teacher. Thank to Dr. Richard Weaver and Dr. Jim Gregory, for help in preparing my presentation. Thanks to Dr. Mike Schoenecke for his outstanding teaching skills and for giving me confidence as a writer, and thanks to Dr. Leon Higdon for his support and encouragement. I am eternally grateful to Dr. Janet Cooper for all of her help as a director, playwrighting teacher, and mentor. Special thanks also goes to Dr. Constance Kuriyama for her careful attention to detail and her continued help in preparing this document for the future. Special thanks to Jean Ann Cantore and all of my friends in the Texas Tech School of Engineering for encouragement and friendship. This document would never have been possible without the training and support of my family. I want to thank my parents, and especially thank Dr. David R. LeMaster for setting an example and giving me a goal. -

I Me Mime Wayne Koestenbaum’S Wide-Ranging Homage to a Silent Movie Star Noah Isenberg

FILM I Me Mime Wayne koestenbaum’s wide-ranging homage to a silent movie star NOAH ISENBERG THE ANatOMY OF HARPO MARX by WAyNe koesTeNbAum berkeLey: uNIversITy of CALIforNIA Press. 336 pages. $30. riginally I intended to write a The book devotes one chapter to each of sing, ‘Last dance, last chance.’ The fear that a his chapter on Room Service (1938). “A tie is “ book about Harpo’s relation to the thirteen major films in which Harpo detail doesn’t belong in this book inspires me a circumcision motto, a trace of foresaken O history and literature,” remarks starred alongside brothers Groucho and to insist that everything belongs. What’s the skin.” But isn’t a tie sometimes just a tie? Wayne Koestenbaum on the first page of his Chico (and, in the early pictures, Zeppo). point of ‘book’ if it can’t include scraps? Isn’t Koestenbaum seems to recognize the tunnel fittingly zany, aphoristic, and meandering The pages present a string of prose snapshots, inclusiveness the point of the big store, a ware- vision that can result from pursuing his obses- study of the great mime of Marx Brothers richly illustrated with several dozen screen house of points, some insufficiently pointed?” sions too doggedly, admitting at one point, fame. “A tiny chapter on Harpo and Hegel. A grabs—a term whose semantic ambiguities The author, in other words, grants himself “I’ve been reading too much Lacan.” tiny chapter on Harpo and Marx. A tiny chap- and erotic undertones would seem to invite carte blanche to include what he wishes. -

Torrance Press

Pag* A-6 THE PRESS Sunday, November 12, 1961 Presidency U.S. Steel Hour Toys-50,000 of Them- Image Topic Produces Play, Sub jecl of DuPonl Show llo\v do you nut together trailer for rest and relaxa Clifff Robertson will por an hour-long television show tion between takes. * For While tray a sensitive genius who in New York City's Central 18.000 Feet of Film "Ah, Peter or shall I tries to shut love out of his Park, when it daily attracts Exposed during the pro life, in "Man on the Moun thousands of onlookers and duction were 18.000 feet of call you Professor Odegard? taintop," on the U.S. Steel behind Fifth Peter, let me just throw the sun fleets film and 12 one-hour reels some thoughts at you. Hour, Wednesday at 10 p.m. Avenue skyscrapers? of television tape. Each day, via Channel 2. Co-producers John A. Aar 'our miles of wire and cable "I believe that the presi Written by Robert Alan vere laid out on the park's dency hovers over the Amer on and .Tesse Zousmer, whose Arthur, the teleplay win "The Wonderful World of slopes and pathways. ican imagination like a sa introduce a new star] Salonn cerdotal office the only Toys" will be presented on In addition to Harpo's Jens, to Steel Hour ami NBC-TV's "Du Pont Show railer, mobile equipment on thing sacred and holy in ail iences. American life." of the Week" tonight from he set included an NBC re Horace Mann R o r d e n 10-11 p.m. -

Groucho Marx Can Make You a Better Lawyer GROUCHO DID SOMETHING WE SHOULD ALL HOPE to DO: BE BRILLIANT and STAY RELEVANT

Gregory W. Alarcon LOS ANGELES SUPERIOR COURT July 2019 Issue Groucho Marx can make you a better lawyer GROUCHO DID SOMETHING WE SHOULD ALL HOPE TO DO: BE BRILLIANT AND STAY RELEVANT In my room, growing up, was a Groucho Marx has had a personal has been practicing law for 20 or 30 poster of the Marx Brothers. They would impact in my life three times. The first years, has only tried one or two jury become silent mentors to me, teaching was through my adolescence – watching trials. Many mistakes made by counsel me through their films and writings, to the films – and seeing his glorious sneer would never have been made had that communicate better, to entertain, and to from the poster of the Marx Brothers in lawyer gone through the necessary make an impact. There was Harpo, with my room, which influenced my thinking, preparation from years of training his clownish wig, his harp, his huge eyes, my attitude, and my approach to life. before persuasively arguing a case in his gift of mime, and his bits of wisdom The second was when I took a class front of a jury. which made surrealist Salvador Dali a on filmmaking immediately before law fan. There was Chico, with his mock school from Nat Perrin (1905 -1998) a Surround yourself with people foreign accent, forever sporting non- screenwriter and producer who began as smarter than you sequiturs which later became a model for a lawyer but switched careers when he Contrary to trying to be the smartest future clueless characters with a secret became one of the writers of the Marx person in the room, Groucho Marx sur- agenda.