The Analogical Parallax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

Guide to the Harpo Marx Papers

Guide to the Harpo Marx papers NMAH.AC.1290 NMAH Staff Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series : Sound Recordings: Original Audio Discs, 1947, 1949, 1956...................... 2 Series : Working Box 1............................................................................................ 6 Series : Working Box 2............................................................................................ 8 Series : Working Box 3.......................................................................................... 11 Series : Working Box 4.......................................................................................... 13 Series : Working Box 5.......................................................................................... 14 Series : Working Box 6.......................................................................................... 15 Harpo Marx Papers NMAH.AC.1290 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Harpo Marx Papers -

Jewish Culture Spring 2020 Welcome Table of Contents

QUENCH YOUR THIRST FOR JEWISH CULTURE SPRING 2020 WELCOME TABLE OF CONTENTS It isn’t a coincidence that Passover, the holiday that celebrates freedom, is in the Spring. That’s when flowers Welcome 2 bloom, temperatures rise, and, after a winter trapped indoors, we all get to play outside. Buying Tickets 3 So it also isn’t coincidence that freedom and playfulness are undercurrents of JArts’ Spring 2020 season. You’ll savor it through special menu items at Boston’s only Israeli restaurant week. You’ll hear it in the music of Support JArts 4 the unforgettable Argentinian musical duo who will be our Rukin Memorial artists-in-residence. You’ll be surprised and delighted with it in our new JLab series of experimental, unexpected works. And you’ll experience it through The Shape of Play, our public art installation in downtown Boston by artist Sari Carel, following our award-winning Events 6 Pathways to Freedom project. Staff, Contact Info, 20 Whether in a public art project or at a Seder, fun and play are far from frivolous. From the ancient afikomen to Sponsors today’s latest parody songs, people have always incorporated playful elements for passing stories like the Exodus story on to the next generation. Leadership 20 Nachman of Breslov declared “Freedom is the world of joy.” The connections between freedom, laughter, and play Season Calendar 23 are core to the Jewish experience. We hope you will join us this season. Laura Mandel Joey Baron Executive Director Artistic Director 2 BUYING TICKETS IS EASY ABOUT THE JEWISH ARTS COLLABORATIVE ONLINE JArts™ brings people together to explore and celebrate the diverse, world of Jewish art, culture, and creative expression. -

American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2013 "We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Samantha M., ""We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49)" (2013). Masters Theses. 162. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Long For a Home”: American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2013 To my late grandfather whose love for history and higher education continues to inspire my work. Despite having never entered a college classroom, he was, and continues to be, the greatest professor I ever had. ii Acknowledgments The seeds of this project were sown in the form of a term paper for an undergraduate course on the history and politics of the Middle East at Lynchburg College with Brian Crim. His never-ending mentorship and friendship have shaped my research interests and helped prepare me for the trials and tribulations of graduate school. -

Class, Language, and American Film Comedy

CLASS, LANGUAGE, AND AMERICAN FILM COMEDY CHRISTOPHER BEACH The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Christopher Beach 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Garamond 11/14 pt. System QuarkXPress [] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beach, Christopher. Class, language, and American film comedy / Christopher Beach. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0521 80749 2 – ISBN 0 521 00209 (pb.) 1. Comedy films – United States – History and criticism. 2. Speech and social status – United States. I. Title. PN1995.9.C55 B43 2001 791.43 617 – dc21 2001025935 ISBN 0 521 80749 2 hardback ISBN 0 521 00209 5 paperback CONTENTS Acknowledgments page vii Introduction 1 1 A Troubled Paradise: Utopia and Transgression in Comedies of the Early 1930s 17 2 Working Ladies and Forgotten Men: Class Divisions in Romantic Comedy, 1934–1937 47 3 “The Split-Pea -

Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction Céline Murillo and David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/39864 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.39864 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Céline Murillo and David Roche, “Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 06 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/39864 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.39864 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis... 1 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis. An Introduction Céline Murillo and David Roche 1 This special issue of Miranda is comprised of a selection of articles that were presented at the SERCIA conference entitled “Music & Movies: National and Transnational Perspectives,” organized by Frank Mehring (Radboud University) and Melvyn Stokes (University College London) at Radboud University, Nijmegen, in September 2014. We would like to start by thanking the organizers for a wonderful conference and the SERCIA board for entrusting us with the challenging task of editing this issue. The task was from the start a challenge because the conference confirmed that, even today, the majority of film scholars—that is those who do not have a background in music and musicology—remain cautious, if not downright inhibited, when it comes to studying music in film. -

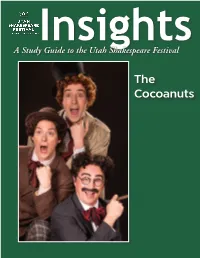

The Cocoanuts the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Cocoanuts The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the inter- pretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, publication manager and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2016, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespearean Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Tasso Feldman (above) as Harpo (Silent Red), Jim Poulos as Chico (Willie Wony Diddydony), and John Plumpis as Mr. Hammer (Groucho) in The Cocoanuts, 2016. The Cocoanuts Contents Information on the Play About the Playwright 4 Characters 7 Synopsis 7 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Marx Brothers on Broadway 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 About the Playwright: The Cocoanuts By Rachelle Hughes Almost a century ago Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright George S. Kauffman joined his creative genius with Songwriter’s Hall of Fame composer and lyricist Irving Berlin to write the Marx Brothers’ first movie and second Broadway play, The Cocoanuts. -

A Century of the Marx Brothers Joseph Mills

T A Century of the Marx Brothers Edited by Joseph Mills C' ,p CAMBRIDGE SCI-IOLARS PUBLISHING A Century of the Marx Brothers, edited by Joseph Mills This book first pub!ished 2007 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2.JA,UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright ID 2007 by Joseph Mills and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 1-84718-240-2;ISBN 13: 9781847182401 CHAPTER ELEVEN THE BIG GREY IR-ELEPHANT: THE PLAY OF LANGUAGE IN THE MARX BROTHERS' SCRIPTS AND IN CHARLES BERNSTEIN'S L=A N=G=U=A=G=E POETRY ZOEBRIGLEY In his collection, Poetic Justice (1979), the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poet, Charles Bernstein begins an untitled poem with the following lines: The elephant appears without the slightest indication that he is demanded. An infinite inappropriateness. Continually learning.' The image of the elephant appears as a surprise or as an inappropriate occurrence, and its appearance indicates that one cannot rest easy in the conventional uses of language. Rather the poet must be in a state of continual "learning" discovering how language empowers some subjects and weakens others. As Bernstein writes in his essay, "Making Words Visible": "We all see words: signs of a language we live inside of. -

FAMILY MATINEES Saturday and Sunday Afternoons

FAMILY MATINEES Saturday and Sunday afternoons DUCK SOUP Saturday, January 15, 2011 12:30 p.m. 1933, 68 min. 35mm print source: Universal Pictures. Directed by Leo McCarey. Screenplay and songs by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby. Produced by Herman J. Mankiewicz. Photographed by Henry Sharp. Production design by Hans Dreier and W. B. Ihnen. Edited by LeRoy Stone. Principal cast: Groucho Marx (as Rufus T. Firefly), Harpo Marx (Pinky), Chico Marx (Chicolini), Zeppo Marx (Lt. Bob Roland), Margaret Dumont (as Mrs. Gloria Teasdale), Raquel Torres (Vera Marcal), Louis Calhern (Trentino), Edmund Breese (Zander), Edgar Kennedy (street vendor). From The Marx Brothers by William Wolf, Pyramid, Satire has always been a virtually dirty word in 1975: Hollywood. Anything that smacks of intellectualism has mostly been shunned by Duck Soup , the Marx Brothers’ last film for executives who find “entertainment” a more Paramount, looms as among the most important in magical word. Therefore, one must take with a their careers. It is a pivotal picture, which reveals grain of salt the protestations that Duck Soup was the social satire of which they were capable, and meant only to be funny, and that it was merely a seeing it again raises anew the question of why this case of finding a new environment for the routines avenue of expansion was closed to them. The of the brothers, who just happened to do a comedy picture is now a special favorite of Marx that spoofs sacred cows. This is not to say that aficionados and for very good reason. It is everything film buffs now read into the film was surrealistic comedy which neatly blends barbs at planned that way. -

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection NMAH.AC.0269 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. and Wendy Shay 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1977, undated..................................................... 6 Series 2: Publications, Manuscripts, and Print Articles by Marx, 1930-1958, undated .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 3: Scripts and Sketches, 1939-1959, undated............................................. -

Preston Sturges & the Marx Bros

Preston Sturges & The Marx Bros. by Richard von Busack “Somebody said that all I needed for success in American life was a bass voice and a muscular handshake, so I seized producers with a powerful grip, looked piercingly into their eyes and asked them in my deepest tones if they doubted for a second if I could direct. “When they said, ‘no’, and I said, “Then when do I start,’ they said, “As soon as you’ve directed for anybody else.” Such was Preston Sturges’ dilemma in the late 1930s. He was one of the best-paid writers in Hollywood, where, as the saying went, you never saw so many unhappy people earning $100,000 a year. He had worked for Goldwyn, MGM and Universal, had writ- ten dialogue for kings and drum majorettes alike, and he was burning to direct. It was during this time that a script of Sturges’ titled “The Vagrant” was being pre- pared for filming. Sturges offered his services as director for the sum of $1. Paramount producer William LeBaron accepted the deal for $10 to make it more official. The script was retitled “The Great McGinty.” In parting, LeBaron warned the novice direc- tor that he’d be happier as a writer: “Shoemaker, stick to your last!” “You show me a man who sticks to his last, and I’ll show you a shoemaker,” Sturges thought to himself, on the staircase out of the office. So began the directing career of Preston Sturges. In a startlingly short rush of creative fervor, which chronologically paralleled the US’s most desperate years during World War II, Sturges directed seven peerless comedies.