<Jhair^Rson Of^The Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

PDF of the Princess Bride

THE PRINCESS BRIDE S. Morgenstern's Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure The 'good parts' version abridged by WILLIAM GOLDMAN one two three four five six seven eight map For Hiram Haydn THE PRINCESS BRIDE This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it. How is such a thing possible? I'll do my best to explain. As a child, I had simply no interest in books. I hated reading, I was very bad at it, and besides, how could you take the time to read when there were games that shrieked for playing? Basketball, baseball, marbles—I could never get enough. I wasn't even good at them, but give me a football and an empty playground and I could invent last-second triumphs that would bring tears to your eyes. School was torture. Miss Roginski, who was my teacher for the third through fifth grades, would have meeting after meeting with my mother. "I don't feel Billy is perhaps extending himself quite as much as he might." Or, "When we test him, Billy does really exceptionally well, considering his class standing." Or, most often, "I don't know, Mrs. Goldman; what are we going to do about Billy?" What are we going to do about Billy? That was the phrase that haunted me those first ten years. I pretended not to care, but secretly I was petrified. Everyone and everything was passing me by. I had no real friends, no single person who shared an equal interest in all games. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Charlie Chaplin's

Goodwins, F and James, D and Kamin, D (2017) Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days: At Work with the Comic Genius. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442278099 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/618556/ Version: Submitted Version Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days At Work with the Comic Genius By Fred Goodwins Edited by Dr. David James Annotated by Dan Kamin Table of Contents Introduction: Red Letter Days 1. Charlie’s “Last” Film 2. Charlie has to “Flit” from his Studio 3. Charlie Chaplin Sends His Famous Moustache to the Red Letter 4. Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Lost Sheep’ 5. How Charlie Chaplin Got His £300 a Week Salary 6. A Straw Hat and a Puff of Wind 7. A bombshell that put Charlie Chaplin ‘on his back’ 8. When Charlie Chaplin Cried Like a Kid 9. Excitement Runs High When Charlie Chaplin “Comes Home.” 10. Charlie “On the Job” Again 11. Rehearsing for “The Floor-Walker” 12. Charlie Chaplin Talks of Other Days 13. Celebrating Charlie Chaplin’s Birthday 14. Charlie’s Wireless Message to Edna 15. Charlie Poses for “The Fireman.” 16. Charlie Chaplin’s Love for His Mother 17. Chaplin’s Success in “The Floorwalker” 18. A Chaplin Rehearsal Isn’t All Fun 19. Billy Helps to Entertain the Ladies 20. “Do I Look Worried?” 21. Playing the Part of Half a Cow! 22. “Twelve O’clock”—Charlie’s One-Man Show 23. “Speak Out Your Parts,” Says Charlie 24. Charlie’s Doings Up to Date 25. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Charlie Chaplin, City Lights

Beeth o v en a ca d em ie . c a r l davis Charlie Chaplin, City Lights DESINGEL 17 FEBRUARI 98 Film met live orkest ism. villanella en Filmmuseum Antwerpen BEETHOVEN ACADEMIE . CARL DAVIS Charlie Chaplin, City Lights DESINGEL 17 FEBRUARI 98 Film met live orkest ism. villanella en Filmmuseum Antwerpen Beethoven Academie Charlie Chaplin, City Lights Carl Davis muzikale leiding de zwerver Charles Chaplin het blinde meisje Virginia Cherrill haar grootmoeder Florence Lee de miljonair Harry Myers bokser Hank Mann scheidsrechter Eddie Baker butler Allan Garcia burgemeester/portier Henry Bergman straatveger/inbreker Albert Austin inbreker Joe Van Meter krantenjongens Robert Parrish, Austen Jewell man op lift Tiny Ward assistente in bloemenwinkel Mrs. Hyams flik Harry Ayers vrouw die op sigaar zit Florence Wicks figurant in restaurantscène Jean Harlow boksers Tom Dempsey, Eddie McAuliffe, Willie Keeler, Victor Alexander productie Chaplin - United Artists producent/regie scenario/montage Charles Chaplin fotografie Roland Totheroh cameramannen Mark Marlatt, Gordon Pollock aanvang filmconcert 20.00 uur regie-assistenten Harry Crocker, Henry Bergman, einde 21.30 uur Albert Austin geen pauze art director Charles D. Hall muziek Charles Chaplin foto's programmaboekje © and property of arrangeur Arthur Johnston productieleider Alt Reeves Roy Export Company Establishment teksten programmaboekje Frank Van der Kinderen duur 86 min coördinatie programmaboekje deSingel Engelstalige tussentitels druk programmaboekje Tegendruk kopie Photoplay Productions SYNOPSIS Een zwerver (de 'Tramp') wordt verliefd op een blind bloe- menverkoopstertje en hoopt het geld te vinden voor de ope ratie die haar het zicht moet teruggeven. Hij papt aan met een excentrieke miljonair die in dronken toestand zeer vrij gevig is, maar eenmaal nuchter een hardvochtig mens. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

December 2020 New Releases

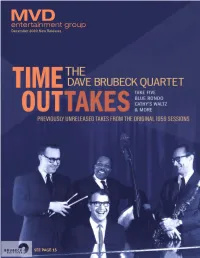

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR.