Thesis with Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

Hello! My Baby Student Guide.Pdf

Goodspeed’s Student Guide to the Theatre is made possible through the generosity of GOODSPEED MUSICALS GOODSPEED GUIDE TO THE THEATRE Student The Max Showalter Center for Education in Musical Theatre HELLO! MY BABY The Norma Terris Theatre November 3 - 27, 2011 _________ CONCEIVED & WRITTEN BY CHERI STEINKELLNER NEW LYRICS BY CHERI STEINKELLNER Student Guide to the Theatre TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW MUSIC & ARRANGEMENTS BY GEORGIA STITT ABOUT THE SHOW: The Story...................………………………………………….3 LIGHTING DESIGN BY JOHN LASITER ABOUT THE SHOW: The Characters...........................……………………………5 ABOUT THE SHOW: The Writers....................…..…………………………………...6 COSTUME DESIGN BY ROBIN L. McGEE Listen Up: Tin Pan Alley Tunes................………………………………................7 SCENIC DESIGN BY A Few Composers + Lyricists..............................……………………………….....8 MICHAEL SCHWEIKARDT Welcome to the Alley!...............…………………………………………………...10 CHOREOGRAPHED BY Breaking into the Boys Club......…………………………………………………...11 KELLI BARCLAY New York City..............................…………………………………………………...12 DIRECTED BY RAY RODERICK FUN AND GAMES: Word Search........................................................................13 FUN AND GAMES: Crossword Puzzle….……………………………...................14 PRODUCED FOR GOODSPEED MUSICALS BY How To Be An Awesome Audience Member…………………......................15 MICHAEL P. PRICE The Student Guide to the Theatre for Hello! My Baby was prepared by Joshua S. Ritter M.F.A, Education & Library Director and Christine Hopkins, -

Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association

QuarterQuarterthe deckdeck LogLog Membership publication of the Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association. Publishes quarterly –– Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Not sold on a subscription basis. The Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association is a Non-Profit Corporation of Active Duty Members, Retired Members, Reserve Members, and Honorably Discharged Former Members of the United States Coast Guard who served in, or provided direct support to combat situations recognized by an appropriate military award while serving as a member of the United States Coast Guard. Volume 19, Number 4 Winter 2004 What Are They Doing Now? Reuniting With Previous CGCVA Coast Guard Persons of the Year At our 2002 Convention & Reunion in Reno, we voted to with the severely injured pilot, Kelly jumped into the frigid 20- make all those selected as CGCVACoast Guard Persons of the foot seas and swam to the survivor. In addition to his injuries Year Honorary Life Members of our Association (if they and hypothermia, the pilot was entangled in his parachute and weren’t otherwise eligible). Memberships were presented to it took Kelly 20 minutes to free him so he could be hoisted to the 2001 recipient (SN Gavino Ortiz of USCG Station South the hovering aircraft. By this time, Kelly herself was suffering Padre Island, Texas), 2002 recipient (AVT3 William Nolte of from hypothermia since her dry suit had leaked, allowing cold USCG Air Station Houston, Texas), and 2003 recipient BM1 water to enter. A second Coast Guard aircraft arrived to search Jacob Carawan of the USCGC Block Island). The first time we for the weapons officer whose body was ultimately found made the award presentation entangled in his parachute was 1991 and we have hon- about 12-feet beneath the life ored a deserving Coast Guard raft. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

Frank Ferrante Reprises His Acclaimed “An Evening with Groucho” at Bucks County Playhouse As Part of Visiting Artists Program • February 14 – 25, 2018

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: FHPR – 215-627-0801 Sharla Feldscher, #101, cell 215-285-4868, [email protected] Hope Horwitz, #102, cell 215-760-2884, [email protected] Photos of Frank Ferrante visiting former home of George S. Kaufman, now Inn of Barley Sheaf Farm: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/70z5e7y6b1p4odd/AAAAw4xwq7EDYgBjcCxCf8p9a?dl=0 Photos by Sharla Feldscher “GROUCHO” RETURNS TO NEW HOPE! Frank Ferrante Reprises His Acclaimed “An Evening with Groucho” at Bucks County Playhouse as part of Visiting Artists Program • February 14 – 25, 2018 Special Preview was Feb. 12, 2018 when Ferrante visited Inn of Barley Sheaf Farm in Bucks County, the former home of Playwright George S. Kaufman where Marx Brothers visited often. New Hope, PA (February 14, 2018) – The quick-witted American actor and icon, Groucho Marx was a frequent visitor to New Hope and Bucks County. Now nearly 41 years after his death, Groucho makes a hilarious return to Bucks — this time in the form of award-winning actor Frank Ferrante in the global comedy hit, “An Evening with Groucho.” The show is presented February 14 – 25 at Bucks County Playhouse as part of the 2018 Visiting Artists Series. As a special preview, Mark Frank, owner of The Inn at Barley Sheaf Farm, invited Frank Ferrante, the preeminent Groucho Marx performer, and press on a tour of this historic former home of Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright, George S. Kaufman. The duo provided insight into the farm’s significance and highlighted Groucho’s role in Bucks County’s rich cultural history. Amongst the interesting facts shared on the preview, Ferrante told guests: • George S. -

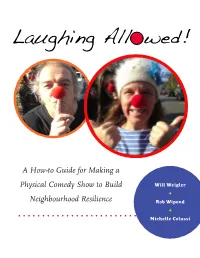

Laughing Allowed! It’S Funny Because It’S True

Using Physical Comedy for Building Resilience Laughing Allowed! It’s funny because it’s true A How-to Guide for Making a Physical Comedy Show to Build Will Weigler + Neighbourhood Resilience Rob Wipond + Michelle Colussi Introduction In the fall of 2014, a group of people in Victoria, and can offer new ways of exploring, discussing Canada who shared both an interest in their and resolving shared challenges. Both the neighbourhood and a quirky sense of humour development process and the show itself created were brought together to explore a question: a vibrant space for people to talk freely about Could they turn their experiences of the ups and their common challenges. The post-performance downs of neighbourhood leadership, activism conversation with the audience and project and volunteering into physical comedy sketches? participants had nearly as much shared laughter Project participants were trained in theatre and and applause as the show itself, with people physical comedy techniques over six weeks and eager to talk about what resonated most for them collaboratively developed a show called Laughing personally in the different scenes. Looking at the Allowed! The Slapstick World of Neighbourhood problems in light-hearted ways led to different Activism. The one-night-only performance drew kinds of conversations about how to bring about one hundred and fifty audience members, most changes. A full-length video and shorter clips of of whom stayed for a focused conversation the show were posted for free online, and they afterwards to explore the show’s themes. too have subsequently been used by other groups Laughing Allowed! was such a success that, to prompt reflection and discussion at their own as the facilitators, we’ve developed this guide gatherings. -

Dr. Demento Back As Our Guest of Honor to Help Celebrate 50 Years of the Dr

2 Welcome to FuMPFest 2021! We are thrilled to welcome Dr. Demento back as our guest of honor to help celebrate 50 years of The Dr. Demento Show! We’ve got a great lineup for you this weekend, including Dr. Demento’s Festival of Dementia, performances by some amazing artists, The Logan Awards, and, of course, Dumb Parody Ideas. Be sure to grab a Bin- go card and follow along with the ridiculousness. And please wear a mask. We plan to have fun, but we need to keep everyone safe. Table of Contents Page Content Guidelines for Parents 8 FuMP Bingo 14 Guests 5 Local Area Map 15 Merchandise Listing 12 Panels 4 Program Schedule 8 Special Thanks Dr. Demento, John Cafiero, Luke Ski, Insane Ian, Chris Mezzolesta, Bill Rockwell, Bad Beth and Beyond, Bill Larkin, Carla Ulbrich, Carrie Dahlby, Ian Lockwood, Nuclear Bubble Wrap, Ross Childs, Steve Goodie, The Gothsicles, Worm Quartet, Captain Ambivalent, Susan “Sulu” Dubow, Jungle Judy, Beefalo Bill, Artie Barnes, Jeff Morris, Eclectic Lee, Sara Trice, Dr. Don, MadMike, all of our spon- sors, HTB Press, Jacob Dawson and the Dorsai Irregulars, Dina Chi- appetta, Aaron Bastable, Aron Kamm, Don Bundy and Bundy Audio, Brett Ferlin, Jon “Bermuda” Schwartz, Mr. Tuesday, Ellen Macas, Kristina Winslow, Brett Krause, Doornail, James Russell, Ken Sher- lock, and of course everyone who actually showed up to this thing! FuMPFest Staff Tom Rockwell - Con Chair... aka Devo Spice, the guy who does things Luke Sienkowski - Co-chair, aka the great Luke Ski, who tells Devo to do things Chris Mezzolesta - Sound Guy, Tile Guy, Power Salad performer Ian Bonds - aka Insane Ian, hosting, so Devo doesn’t have to 3 Panel Descriptions Friday Opening Ceremonies - Welcome The Sidekicks - Join Sulu, to the con! Join us for an over- Jungle Judy (via Zoom), and view of what we have in store more to discuss being a sidekick this weekend and see this year’s on The Dr. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Guide to the Harpo Marx Papers

Guide to the Harpo Marx papers NMAH.AC.1290 NMAH Staff Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series : Sound Recordings: Original Audio Discs, 1947, 1949, 1956...................... 2 Series : Working Box 1............................................................................................ 6 Series : Working Box 2............................................................................................ 8 Series : Working Box 3.......................................................................................... 11 Series : Working Box 4.......................................................................................... 13 Series : Working Box 5.......................................................................................... 14 Series : Working Box 6.......................................................................................... 15 Harpo Marx Papers NMAH.AC.1290 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Harpo Marx Papers -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Guide to the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, 1838-2017

Guide to the Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art, 1838-2017 Descriptive Summary Title : Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art Creator: Mahan, Charles S. (1938 -) Dates : 1838-2005 ID Number : M49 Size: 72 Boxes Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections University of South Florida Libraries 4202 East Fowler Ave., LIB122 Tampa, Florida 33620 Phone: 813-974-2731 - Fax: 813-396-9006 Contact Special Collections Administrative Summary Provenance: Mahan, Charles S., 1938 - Acquisition Information: Donation. Access Conditions: None. The contents of this collection may be subject to copyright. Visit the United States Copyright Office's website at http://www.copyright.gov/for more information. Preferred Citation: Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, Special Collections Department, Tampa Library, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. Biographical Note Charles S. Mahan, M.D., is Professor Emeritus, College of Public Health and the Lawton and Rhea Chiles Center for Healthy Mothers and Babies. Mahan received his MD from Northwestern University and worked for the University of Florida and the North Central Florida Maternal and Infant Care Program before joining the University of South Florida as Dean of the College of Public Health (1995-2002). University of South Florida Tampa Library. (2006). Special collections establishes the Dr. Charles Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art. University of South Florida Library Links, 10(3), 2-3. Scope Note In addition to Disney animation catalogs, illustrations, lithographs, cels, posters, calendars, newspapers, LPs and sheet music, the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art includes numerous non-Disney and political illustrations that depict American humor and cartoon art.