Not Designated for Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

Guide to the Harpo Marx Papers

Guide to the Harpo Marx papers NMAH.AC.1290 NMAH Staff Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series : Sound Recordings: Original Audio Discs, 1947, 1949, 1956...................... 2 Series : Working Box 1............................................................................................ 6 Series : Working Box 2............................................................................................ 8 Series : Working Box 3.......................................................................................... 11 Series : Working Box 4.......................................................................................... 13 Series : Working Box 5.......................................................................................... 14 Series : Working Box 6.......................................................................................... 15 Harpo Marx Papers NMAH.AC.1290 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Harpo Marx Papers -

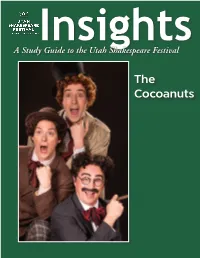

The Cocoanuts the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Cocoanuts The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the inter- pretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, publication manager and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2016, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespearean Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Tasso Feldman (above) as Harpo (Silent Red), Jim Poulos as Chico (Willie Wony Diddydony), and John Plumpis as Mr. Hammer (Groucho) in The Cocoanuts, 2016. The Cocoanuts Contents Information on the Play About the Playwright 4 Characters 7 Synopsis 7 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Marx Brothers on Broadway 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 About the Playwright: The Cocoanuts By Rachelle Hughes Almost a century ago Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright George S. Kauffman joined his creative genius with Songwriter’s Hall of Fame composer and lyricist Irving Berlin to write the Marx Brothers’ first movie and second Broadway play, The Cocoanuts. -

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection NMAH.AC.0269 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. and Wendy Shay 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1977, undated..................................................... 6 Series 2: Publications, Manuscripts, and Print Articles by Marx, 1930-1958, undated .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 3: Scripts and Sketches, 1939-1959, undated............................................. -

Preston Sturges & the Marx Bros

Preston Sturges & The Marx Bros. by Richard von Busack “Somebody said that all I needed for success in American life was a bass voice and a muscular handshake, so I seized producers with a powerful grip, looked piercingly into their eyes and asked them in my deepest tones if they doubted for a second if I could direct. “When they said, ‘no’, and I said, “Then when do I start,’ they said, “As soon as you’ve directed for anybody else.” Such was Preston Sturges’ dilemma in the late 1930s. He was one of the best-paid writers in Hollywood, where, as the saying went, you never saw so many unhappy people earning $100,000 a year. He had worked for Goldwyn, MGM and Universal, had writ- ten dialogue for kings and drum majorettes alike, and he was burning to direct. It was during this time that a script of Sturges’ titled “The Vagrant” was being pre- pared for filming. Sturges offered his services as director for the sum of $1. Paramount producer William LeBaron accepted the deal for $10 to make it more official. The script was retitled “The Great McGinty.” In parting, LeBaron warned the novice direc- tor that he’d be happier as a writer: “Shoemaker, stick to your last!” “You show me a man who sticks to his last, and I’ll show you a shoemaker,” Sturges thought to himself, on the staircase out of the office. So began the directing career of Preston Sturges. In a startlingly short rush of creative fervor, which chronologically paralleled the US’s most desperate years during World War II, Sturges directed seven peerless comedies. -

The Story of the MARX Brothers Paternal Family

15/07/2008 09:06 2008-07-11 The Story of the MARX Brothers Paternal Family This query was initiated by a member of the French Cercle de Genealogie Juive, who wrote to me: >It is said that Sam Marx, the father of the Marx Brothers, was born in Strasbourg, but was never >proved. What do you think about it? 4 months later, I arrived at the solution and, for your comfort, will begin to explain that there were 3 generations of Simon MARX Simon Marx (I ) 1804 oo Babet Weil Simon Marx (II) 1830 Hochfelden, Alsace -1901 Strasbourg, Alsace oo Adel Levi, alias Haennchen, Johanna Isaak 1839 Lorsch, Prussia-1910 Strasbourg Alsace Simon Marx (III) 1859 Mertzwiller Alsace -1933 Los Angeles, CA,, USA oo Minnie Schoenberg 1864 Dornum, Ostfrieseland, Prussia.- 1929 New York I will not explain in detail my lonely query, the main thing being the result. Thanks to Google, I began to search all that was published on the Marx Brothers and their parents, often leading to wrong tracks, as certain authors declared that the father was born in Alsace and sometimes in Strasbourg, after 1860. For that reason, I wasted my time in searching 1860 and later. First problem: the first name: Samuel or Simon ? In the questions-answers of Revue of the Cercle de Genealogie Juive, (n° 80 (still 2001!), 3470 and 4696): almost the same question: does somebody know something about?? On http://www.cineartistes.com I read: C’est à Strasbourg en Alsace que commence la saga de la famille Marx. En effet Simon, le futur père de Chico Marx (et des autres!) y voit le jour en 1861, dans le quartier juif de la ville. -

Brush, and a Director an Army

03 Luxembourg City Film Festival The Marx Brothers L’Ecole de Berlin Jean-Louis Trintignant Festival du Cinéma Espagnol « A poet needs a pen, a painter a brush, and a director an army. » Orson Welles www.cinematheque.lu Mars 2021 Informations pratiques 3 Sommaire La jauge de places disponibles étant plus Tableau synoptique 4 Cinéma 17, place du Théâtre Abonnement gratuit réduite qu’habituellement, il est recom- L-2613 Luxembourg au programme mensuel Université Populaire du Cinéma 6 mandé d’acheter les tickets à l’avance en Tél. : 4796 2644 ligne sur www.luxembourg-ticket.lu. Le Monde en doc 8 Tickets online [email protected] Luxembourg City Film Festival 10 sur www.cinematheque.lu Uniquement les personnes du même www.luxembourg-ticket.lu ménage peuvent être assis ensemble. Dans 21 e Festival du Cinéma Espagnol 26 ce cas, il est recommandé de procéder à The Marx Brothers 30 l’achat groupé des billets. L’Ecole de Berlin 38 La caisse du soir pour la vente des billets Jean-Louis Trintignant 42 Bd. Royal R. Willy Goergen est ouverte au public une ½ heure avant les séances (dans la limite des billets dispo- Weekends@Cinémathèque 46 R. des Bains Côte d’Eich Collect Poster treasures Cinémathèque’s Archive! the the from nibles). Le paiement par carte y est privilégié. Cinema Paradiso 52 R. Beaumont Des sièges numérotés seront attribués aux L’affiche du mois 59 détenteurs de tickets. Il est impératif de res- pecter la numérotation des sièges. Baeckerei R. du Fossé R. Aldringen R. Les conditions sécuritaires et sanitaires R. -

Groucho Marx Can Make You a Better Lawyer GROUCHO DID SOMETHING WE SHOULD ALL HOPE to DO: BE BRILLIANT and STAY RELEVANT

Gregory W. Alarcon LOS ANGELES SUPERIOR COURT July 2019 Issue Groucho Marx can make you a better lawyer GROUCHO DID SOMETHING WE SHOULD ALL HOPE TO DO: BE BRILLIANT AND STAY RELEVANT In my room, growing up, was a Groucho Marx has had a personal has been practicing law for 20 or 30 poster of the Marx Brothers. They would impact in my life three times. The first years, has only tried one or two jury become silent mentors to me, teaching was through my adolescence – watching trials. Many mistakes made by counsel me through their films and writings, to the films – and seeing his glorious sneer would never have been made had that communicate better, to entertain, and to from the poster of the Marx Brothers in lawyer gone through the necessary make an impact. There was Harpo, with my room, which influenced my thinking, preparation from years of training his clownish wig, his harp, his huge eyes, my attitude, and my approach to life. before persuasively arguing a case in his gift of mime, and his bits of wisdom The second was when I took a class front of a jury. which made surrealist Salvador Dali a on filmmaking immediately before law fan. There was Chico, with his mock school from Nat Perrin (1905 -1998) a Surround yourself with people foreign accent, forever sporting non- screenwriter and producer who began as smarter than you sequiturs which later became a model for a lawyer but switched careers when he Contrary to trying to be the smartest future clueless characters with a secret became one of the writers of the Marx person in the room, Groucho Marx sur- agenda. -

Mark Vieira, Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince Study

Mark Vieira, Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince Study List Minimum Reading Assignment: chapters I = 1, 2, 5, 6, 7; II = 10, 13, 15, 16; III = 18, 19, 20, 22, Epilogue. (Just over half the book) 1. The Boy Wonder General Manager Universal Studios under Carl Laemmle. He stands up to the formidable Erich von Stroheim! – establishes the tradition of the omnipotent producer. 2. A Funny Little Man Thalberg moves to Metro films; for now he is the darling of LB Mayer. Louis B. Mayer’s idea of a good film. Thalberg’s routine: script goes through several story conferences with producer before approval. 3. Three Shaky Little Stars He hires Norma Shearer; her “wandering eye”; her closeness to Irving. Merger creates MGM – Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer. 4. A Studio Style Thalberg: tendency to give his writers and directors their way if they insist; he is no dictator; also “every great film must have one great scene”. Irving dates several stars. “He who Gets Slapped” MGM’s first big hit. 5. Wicked Stepchildren Stroheim’s ‘Greed’ – “militaristic will”, artist’s ego, and runaway costs; Irving concludes must keep tight rein on directors. The making of the original ‘Ben-Hur’ -- $4 million! But a smash hit. 6. A Business of Personalities Irving is overworked – he personally supervises (too) many films; he has a heart attack. He is paid a lot of money. 1 7. Top of the Heap MGM makes huge profit in 1926. 61-62: The Thalberg procedure for making a film – from selecting the script; the treatment; the script; the script conferences; selection of star; selection of appropriate director; oversight by a producer; Thalberg’s own direct participation, etc. -

Thesis with Numbers

"Strange Interludes?": Carnivalesque Inversions and the Humorous Music of the Marx Brothers Olivia Cacchione A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Larry Starr, Chair Stephen Rumph Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music History © Copyright 2015 Olivia Cacchione ii University of Washington Abstract "Strange Interludes?": Carnivalesque Inversions and the Humorous Music of the Marx Brothers Olivia Cacchione Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Larry Starr Music History The Marx Brothers are known as iconic comedians, and much of the literature on them focuses on the humorous content of their films. Many scholars describe the Marx Brothers as iconoclasts, aiming negative satire at elite institutions. In nearly all of their films, the Marx Brothers perform musical numbers, but very few scholars have looked at these numbers in detail, or incorporated them into analyses of their comedy. Drawing on the writings of Mikhail Bakhtin, Henri Bergson, and Jacques Lacan, this thesis offers an analysis of the films that incorporates their musical numbers as critical elements of their act, and repositions their comedy as positive and carnivalesque, rather than negative and satirical. Connections are drawn between the Marx Brothers' nonmusical humor, including verbal humor, pantomime, and gags, and their musical humor, specifically Chico's piano performances, Harpo's harp performances, and Groucho's songs. iii Introduction and Literature Review In a discussion of the emerging canon in film music studies, Ben Winters cautions against the creation of a class of film music "worthy of discussion" within narrowly defined aesthetic parameters.1 The music of early sound comedies appears at risk of languishing outside this canon, which favors single-author classical Hollywood film scores. -

Celebrity Impersonator

UpStage Productions “Legends Of Country Rock & Soul” The following are PERFORMING IMPERSONATORS (No lip-singing) Those highlighted in red are noted as the best in impersonation ABBA Carpenters, The Aerosmith Carrie Underwood Al Jolson Celine Dion Alice Cooper Charlie Daniels Alanis Morisette Cher Alan Jackson Christina Aguilara Andrew Sisters Connie Francis Andy Gibb Conway Twitty Ann Margaret Cyndi Lauper Aretha Franklin David Bowie Avril Dean Martin Backstreet Boys, The Diana Ross Barbara Streisand Dolly Parton Barry Manilow Donna Summer Barry White Doors, The BB King Duran Duran Beach Boys, The Eagles, The Beatles, The Ella Fitzgerald Bee Gees Elton John Bette Midler Elvis Presley Beyonce Engelbert Humperdink Billy Holiday Enrique Iglesias Billy Idol Eric Clapton Billy Joel E-Street Band (Springsteen) Billy Ray Cyrus Ethel Merman Bing Crosby Everly Brothers, The Black Sabbath Faith Hill Blondie Fats Domino Blues Brothers, The Fleetwood Mac Bobby Darin Four Seasons, The Bob Dylan Four Tops, The Bon Jovi Frank Sinatra Bonnie Raitt Frankie Valli Bono (U2) Freddy Mercury Boy George Garth Brooks Brittany Spears George Harrison Brooks & Dunn George Michael Bruce Springstein George Strait Buddy Holly Grace Slick Cab Callaway Gretchen Wilson Carlos Santana Gloria Estefan Carol Channing Gwen Stephani Hank Williams, Jr. Nat King Cole Hank Williams Snr. Neil Diamond Hanna Montana Neil Young Heart No Doubt Jackie Wilson N-Sync James Brown Ozzy Osbourne Janet Jackson Partridge Family, The Janis Joplin Pasty Cline Jennifer Lopez Pat Benetar Jerry Garcia Patty Labelle Jerry Lee Lewis Paul McCartney Jim Morrison Phil Collins Jimmy Buffett Prince Jimmy Hendrix Queen Joe Cocker Randy Travis Jonas Brothers Rat Pack, The John Denver Ray Charles & Raylettes John Lennon Reba McEntire Johnny Cash Ricky Nelson June Carter Cash Ricky Martin Johnny Mathis Righteous Brothers, The Judds, The Ringo Starr Judy Garland Ritchie Valens Julio Inglesias Robin Williams Justin Timberlake Rod Stewart Karen Carpenter Rolling Stones, The KD Lang Roy Orbison Kenny Chesney Sammy Davis Jr. -

Animal Crackers

Pilot Hans Mlrow of the NAT, Louis Ijanp (Returns to Nome returned to. Nome last’ evening LOCAL NEWS from a flight to Teller and Wales, Capt. Louis Lane, accompanied bringing back Manager Frank Mes by seven other brave and fearless senger art the MOM, accompanied men of the Northern seas, will PBEAM THEATRE Brady Hansen of Bluff, Is an by Bob Roberta, George Nogle and disembark at Nome fjrom the S.S. arrival this week, and is stopping John Hegness, all of whom are Victoria to go forth into the Jaws TWO SHOWS SUNDAY, JUNE 11 7:16 9pM ait the Hotel Alaska. associated with the MGM movie of death, (Bering Sea and Arctic outfit. ocean waters,) in an effort, it is Roibert Ledgerwood, "Pile Driv- -r* said, to carry on polar beaT and er Bob," Is returning to Notbe Chas. Neussler, who for many whaling operations for the MOM was with the Pio- “Eskimo” It Is under- THE WORLD the winter outside. connected picture. OF after years MAN spending neer Mining Co. activities at Little stood they will Join Capt. Hausen WITH *\ The friends of Creek, is a returning passenger on of the Nanuk now at Teller, and many sourdough WILLIAM .POWELL AS THE SILK HATTED RACKETEER Mr«. Jennie Hansen, will be pleas- the Vic. will light the ice and sea elements ed to know that she is returning at the Arctic waters in order to ALSO v “HE TRUMPED HER ACE” to Nome on the Vic. Carl Lomen. President of the obtain the desired Action pictures. WITH Lomen Reindeer Corporation, is an Welcome back home Louis.