AMTRAK and Its Relationship to Maintenance-Of-Way Activities In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sopkin to Lead '49 Drive; UJA Caravan Train Here

----- ·empl e Bt: th- EL. Broad & Gl cnh~m St$. Only An51lo-Jewi1h Serving 30,000 Newspaper in This State in Rhode Island VOL. XXXIV, NO. 5 FRIDAY, APRIL 8, 1949 PROVIDENCE. R. I . TWENTY-FOUR PAGES 7 CENTS THE COPY Sopkin to Lead '49 Drive; UJA Caravan Train Here Li'I Abner Creator, Miss America Here Sun. Speakers ·Stress Capacity Crowd Need of U. S. Aid Attends Rally The a ppointment of Alvin A. j know that you will not refuse. Sopkin as chairman of the 1949 ; ' "We have it within our power fund-ra ising campa ign of the I to make "Homecoming-1949" the General J ewish Committee of realization of our dreams and Providence was announced Tues hopes of the past decade." day during the visit of the "Cara- I Economy In Danger van of Hope" train to this city. The need of United States aid This will m ark the fifth straight i to Israel and the DP's was the year that Sopkin has headed the keynote of the addresses delivered GJC's annual drive, which will by the speakers at Tuesday even start on Labor Day. ing's rally. Max Lerner, noted In his acceptance address, made columnist , author and lecturer, Tuesd ay evening at the Rhode told the packed throng that the Island School of Design auditor DP camps of Europe must be ium, where the "Caravan of Hope" e m p t i e d this year. Terming program was held before a capa Europe a cemetery, Lerner asserted city audience, Sopkin urged all , that if we fail to get the DP's contributors to the 1948 campaign f out of the camps, "their blood to pay their pledges at once, in I ALVIN A. -

The Signal Bridge

THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Volume 18 NEWSLETTER OF THE MOUNTAIN EMPIRE MODEL RAILROADERS CLUB Number 5B MAY 2011 BONUS PAGES Published for the Education and Information of Its Membership NORFOLK & WESTERN/SOUTHERN RAILWAY DEPOT BRISTOL TENNESSEE/VIRGINIA CLUB OFFICERS LOCATION HOURS President: Secretary: Newsletter Editor: ETSU Campus, Business Meetings are held the Fred Alsop Donald Ramey Ted Bleck-Doran: George L. Carter 3rd Tuesday of each month. Railroad Museum Meetings start at 7:00 PM at Vice-President: Treasurer: Webmaster: ETSU Campus, Johnson City, TN. John Carter Duane Swank John Edwards Brown Hall Science Bldg, Room 312, Open House for viewing every Saturday from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. Work Nights each Thursday from 5:00 pm until ?? APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 2 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 3 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE II scheme. The "stripe" style paint schemes would be used on AMTRAK PAINT SCHEMES Amtrak for many more years. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Phase II Amtrak paint schemes or "Phases" (referred to by Amtrak), are a series of livery applied to the outside of their rolling stock in the United States. The livery phases appeared as different designs, with a majority using a red, white, and blue (the colors of the American flag) format, except for promotional trains, state partnership routes, and the Acela "splotches" phase. The first Amtrak Phases started to emerge around 1972, shortly after Amtrak's formation. Phase paint schemes Phase I F40PH in Phase II Livery Phase II was one of the first paint schemes of Amtrak to use entirely the "stripe" style. -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Appendix 6-B: Chronology of Amtrak Service in Wisconsin

Appendix 6-B: Chronology of Amtrak Service in Wisconsin May 1971: As part of its inaugural system, Amtrak operates five daily round trips in the Chicago- Milwaukee corridor over the Milwaukee Road main line. Four of these round trips are trains running exclusively between Chicago’s Union Station and Milwaukee’s Station, with an intermediate stop in Glenview, IL. The fifth round trip is the Chicago-Milwaukee segment of Amtrak’s long-distance train to the West Coast via St. Paul, northern North Dakota (e.g. Minot), northern Montana (e.g. Glacier National Park) and Spokane. Amtrak Route Train Name(s) Train Frequency Intermediate Station Stops Serving Wisconsin (Round Trips) Chicago-Milwaukee Unnamed 4 daily Glenview Chicago-Seattle Empire Builder 1 daily Glenview, Milwaukee, Columbus, Portage, Wisconsin Dells, Tomah, La Crosse, Winona, Red Wing, Minneapolis June 1971: Amtrak maintains five daily round trips in the Chicago-Milwaukee corridor and adds tri- weekly service from Chicago to Seattle via St. Paul, southern North Dakota (e.g. Bismark), southern Montana (e.g. Bozeman and Missoula) and Spokane. Amtrak Route Train Name(s) Train Frequency Intermediate Station Stops Serving Wisconsin (Round Trips) Chicago-Milwaukee Unnamed 4 daily Glenview Chicago-Seattle Empire Builder 1 daily Glenview, Milwaukee, Columbus, Portage, Wisconsin Dells, Tomah, La Crosse, Winona, Red Wing, Minneapolis Chicago-Seattle North Coast Tri-weekly Glenview, Milwaukee, Columbus, Portage, Wisconsin Hiawatha Dells, Tomah, La Crosse, Winona, Red Wing, Minneapolis 6B-1 November 1971: Daily round trip service in the Chicago-Milwaukee corridor is increased from five to seven as Amtrak adds service from Milwaukee to St. -

Effect of Vehicle Performance at High Speed and High Cant Deficiency

Proceedings of the ASME/ASCE/IEEE 2011 Joint Rail Conference JRC2011 March 16-18, 2011, Pueblo, Colorado, USA JRC2011-56066 EXAMINATION OF VEHICLE PERFORMANCE AT HIGH SPEED AND HIGH CANT DEFICIENCY Brian Marquis Jon LeBlanc U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, Volpe Innovative Technology Administration, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States Ali Tajaddini U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Rail Road Administration, Office of Research and Development, Washington D.C., United States ABSTRACT The research for this paper was part of work done for the FRA In the US, increasing passenger speeds to improve trip time to support the FRA Railroad Safety Advisory Committee usually involves increasing speeds through curves. Increasing (RSAC) Track Working Group’s Vehicle Track Interaction speeds through curves will increase the lateral force exerted on (VTI) Task Force. The mission of the VTI task force was to track during curving, thus requiring more intensive track update Parts 213 and 238 of the Code of Federal Regulations maintenance to maintain safety. These issues and other (CFR) regarding rules for high speed (above 90mph) and high performance requirements including ride quality and vehicle cant deficiency (about 5 inches) operations. The task force stability, can be addressed through careful truck design. focused on a number of issues including refinement of VTI Existing high-speed rail equipment, and in particular their safety criteria, track geometry standards, vehicle qualification bogies, are better suited to track conditions in Europe or Japan, procedures and requirements and track inspection in which premium tracks with little curvature are dedicated for requirements, all with a focus on treating the vehicle and track high-speed service. -

Accessibility in Rail Facilities

9/7/2017 Accessibility in Rail Facilities Kenneth Shiotani Senior Staff Attorney National Disability Rights Network 820 First Street Suite 740 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-9514 x 126 [email protected] September 2017 1 ADA Transportation Provisions Making Transportation Accessible was a major focus of the statutory provisions of the ADA PART B - Actions Applicable to Public Transportation Provided by Public Entities Considered Discriminatory [Subtitle B] SUBPART I - Public Transportation Other Than by Aircraft or Certain Rail Operations [Part I] 42 U.S.C. § 12141 – 12150 Definitions – fixed route and demand responsive, requirements for new, used and remanufactured vehicles, complementary paratransit, requirements in new facilities and alterations of existing facilities and key stations SUBPART II - Public Transportation by Intercity and Commuter Rail [Part II] 42 U.S.C. § 12161- 12165 Detailed requirements for new, used and remanufactured rail cars for commuter and intercity service and requirements for new and altered stations and key stations 2 1 9/7/2017 What Do the DOT ADA Regulations Require? Accessible railcars • Means for wheelchair users to board • Clear path for wheelchair user in railcar • Wheelchair space • Handrails and stanchions that do create barriers for wheelchair users • Public address systems • Between-Car Barriers • Accessible restrooms if restrooms are provided for passengers in commuter cars • Additional mode-specific requirements for thresholds, steps, floor surfaces and lighting 3 What are the different ‘modes’ of passenger rail under the ADA? • Rapid Rail (defined as “Subway-type,” full length, high level boarding) 49 C.F.R. Part 38 Subpart C - NYCTA, Boston T, Chicago “L,” D.C. -

State of Indiana

Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2007 State of Indiana Amtrak Service & Ridership Amtrak operates three long-distance trains through Indiana: • The Capitol Limited (daily Chicago-Waterloo-Cleveland-Pittsburgh-Washington, D.C.) • The Cardinal (tri-weekly Chicago-Indianapolis-Cincinnati-New York) • The Lake Shore Limited (daily Chicago-South Bend-Cleveland-Buffalo-Boston/New York) Amtrak also operates one corridor train, the Hoosier State (four days per week Indianapolis-Lafayette- Chicago), which operates on the days that the Cardinal does not. Additionally, the Chicago-Detroit Wolverine serves Hammond-Whiting and Michigan City with three daily round trips. During FY07 Amtrak served the following Indiana locations: City Boardings + Alightings Connersville 497 Crawfordsville 4,431 Dyer 1,723 Elkhart 11,718 Hammond-Whiting 6,457 Indianapolis 29,110 Lafayette 18,483 Michigan City 1,941 Rensselaer 1,630 South Bend 15,856 Waterloo 16,217 Total Indiana Station Usage: 108,066 Procurement/Contracts Amtrak expended $9,874,137 for goods and services in Indiana in FY07. Most of this money, $6,924,792 was spent in Indianapolis. Amtrak Government Affairs: January 2008 Employment At the end of FY07, Amtrak employed 780* Indiana residents. Total wages of Amtrak employees living in Indiana were $37,754,274* during FY07. *Due to a change in methodology, FY07 employment and wage figures are not directly comparable to those reported in prior years. Major Facilities Amtrak’s principal heavy maintenance facility is located in Beech Grove, southeast of Indianapolis. Here, approximately 550 employees rebuild and overhaul Amtrak’s Superliner, Viewliner, Surfliner, Hi-Level, Heritage, and Horizon car fleets. P32, P42, and F59 locomotives also are overhauled and rebuilt here for use across the Amtrak system. -

Amtrak Station Program and Planning Guidelines 1

Amtrak Station Program and Planning Guidelines 1. Overview 5 6. Site 55 1.1 Background 5 6.1 Introduction 55 1.2 Introduction 5 6.2 Multi-modal Planning 56 1.3 Contents of the Guidelines 6 6.3 Context 57 1.4 Philosophy, Goals and Objectives 7 6.4 Station/Platform Confi gurations 61 1.5 Governing Principles 8 6.5 Track and Platform Planning 65 6.6 Vehicular Circulation 66 6.7 Bicycle Parking 66 2. Process 11 6.8 Parking 67 2.1 Introduction 11 6.9 Amtrak Functional Requirements 68 2.2 Stakeholder Coordination 12 6.10 Information Systems and Way Finding 69 2.3 Concept Development 13 6.11 Safety and Security 70 2.4 Funding 14 6.12 Sustainable Design 71 2.5 Real Estate Transactional Documents 14 6.13 Universal Design 72 2.6 Basis of Design 15 2.7 Construction Documents 16 2.8 Project Delivery methods 17 7. Station 73 2.9 Commissioning 18 7.1 Introduction 73 2.10 Station Opening 18 7.2 Architectural Overview 74 7.3 Information Systems and Way Finding 75 7.4 Passenger Information Display System (PIDS) 77 3. Amtrak System 19 7.5 Safety and Security 78 3.1 Introduction 19 7.6 Sustainable Design 79 3.2 Service Types 20 7.7 Accessibility 80 3.3 Equipment 23 3.4 Operations 26 8. Platform 81 8.1 Introduction 81 4. Station Categories 27 8.2 Platform Types 83 4.1 Introduction 27 8.3 Platform-Track Relationships 84 4.2 Summary of Characteristics 28 8.4 Connection to the station 85 4.3 Location and Geography 29 8.5 Platform Length 87 4.4 Category 1 Large stations 30 8.6 Platform Width 88 4.5 Category 2 Medium Stations 31 8.7 Platform Height 89 4.6 Category 3 Caretaker Stations 32 8.8 Additional Dimensions and Clearances 90 4.7 Category 4 Shelter Stations 33 8.9 Safety and Security 91 4.8 Thruway Bus Service 34 8.10 Accessibility 92 8.11 Snow Melting Systems 93 5. -

Boston-Montreal High Speed Rail Project

Boston to Montreal High- Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 final report Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Feasibility Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... ES-1 E.1 Background and Purpose of the Study ............................................................... ES-1 E.2 Study Overview...................................................................................................... ES-1 E.3 Ridership Analysis................................................................................................. ES-8 E.4 Government and Policy Issues............................................................................. ES-12 E.5 Conclusion.............................................................................................................. -

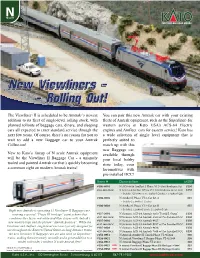

New Viewliners - - Rolling Out!

NScale New Viewliners - - Rolling Out! The Viewliner ® II is scheduled to be Amtrak ®’s newest You can pair this new Amtrak car with your existing addition to its fleet of single-level rolling stock, with fleets of Amtrak equipment, such as the Superliner for planned rollouts of baggage cars, diners, and sleeping western service or Kato USA’s ACS-64 Electric cars all expected to enter standard service through the engines and Amfleet cars for eastern service! Kato has next few years. Of course, there’s no reason for you to a wide selection of single level equipment that is wait to add a new Baggage car to your Amtrak perfectly suited to Collection! match up with this new Baggage car, New to Kato’s lineup of N scale Amtrak equipment available through will be the Viewliner II Baggage Car - a uniquely your local hobby tooled and painted Amtrak car that’s quickly becoming store today, even a common sight on modern Amtrak trains! locomotives with pre-installed DCC! Item # Description MSRP #106-8001 N ACS-64 & Amfleet I Phase VI 5-Unit Bookcase Set $250 #106-8001-DCC N ACS-64 & Amfleet I Phase VI 5-Unit Bookcase Set w/ DCC $330 - Includes ACS-64 #621, 3 x Amfleet I Coaches, 1 x Amfleet I Cafe #106-8002 N Amfleet I Phase VI 2-Car Set A $55 - Includes 2 x Amfleet I Coaches #106-8003 N Amfleet I Phase VI 2-Car Set B $55 Right now Amtrak ® is operating 55 Viewliner ® II Baggage cars, - Includes 1 x Amfleet I Coach, 1 x Amfleet I Cafe wearing a special “Phase III heritage” paint scheme that #137-3001 N Siemens ACS-64 Amtrak #600 “David L Gunn” $150 combines the classic red-white-and-blue stripes with Amtrak’s #137-3001-DCC N Siemens ACS-64 Amtrak #600 w/ Pre-Installed DCC $230 new modern logo and the phrase “Amtrak America”. -

Factors Affecting Commuter Rail Energy Efficiency and Its Comparison with Competing Passenger Transportation Modes

FACTORS AFFECTING COMMUTER RAIL ENERGY EFFICIENCY AND ITS COMPARISON WITH COMPETING PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION MODES BY GIOVANNI C. DIDOMENICO THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Advisers: Professor Christopher P.L. Barkan Senior Research Engineer C. Tyler Dick, P.E. ABSTRACT As concerns about the environmental impacts and sustainability of the transportation sector continue to grow, modal energy efficiency is a factor of increasing importance when evaluating benefits and costs of transportation systems and justifying future investment. Poor assumptions on the efficiency of the system can alter the economics of investment in commuter rail. This creates a need to understand the factors affecting commuter rail energy efficiency and the comparison to competing passenger transportation modes to aid operators and decision makers in the development of new commuter rail lines and the improvement of existing services. This thesis describes analyses to further understand the factors affecting the current energy efficiency of commuter rail systems, how their efficiency may be improved through implementation of various technologies, and how their efficiency compares to competing modes of passenger transportation. After reviewing the literature, it was evident that past studies often conducted energy efficiency analyses and modal comparisons using methods that favored one energy source or competing mode by neglecting losses in the system. Therefore, four methods of energy efficiency analysis were identified and applied to 25 commuter rail systems in the United States using data from the National Transit Database (NTD). -

Design Data on Suspension Systems of Selected Rail Passenger Cars RR 5931R 5021

Design Data on Suspension U.S. Department Systems of Selected Rail of Transportation Federal Railroad Passenger Cars Administration Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20590 ~ail Vehicles & lonents NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMS No. 0704-0188 " Public reporting bulden for this collection of infonnation is estimated to average 1 hourper response. including the time for naviewing instructions. sean:hin9 existing data sources. gathering and maintaining the data needed. and completing and naviewing the collection of information. send comments regarding this bulden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information. including suggestions for reducing this bulden. to WashingICn Headquarters services Dinactorata for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway. SUite 1204, Arlington. VA 22202-4302. and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperworlc Reduction Project (07~188). Washington. DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND OATES COVE~EO July 1996 Final Report ~ober1993-December1994 4. TITLE AND SUBnTLE S. FUNDING NUMBERS Design Data on Suspension Systems of Selected Rail Passenger Cars RR 5931R 5021 6. AUTHORS Alan J. Bing. Shaun R. Berry and Hal B. Henderson 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZAnON NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANlZAnON Arthur D.