Vinayak & Me: "Hindutva" and the Politics of Naming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhakti Movement Part-3

B.A (HONS) PART-3 PAPER-5 DR.MD .NEYAZ HUSSAIN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR & HOD PG DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAHARAJA COLLEGE, VKSU, ARA (BIHAR) Ramanuja He was one of the earliest reformers. Born in the South, he made a pilgrimage to some of the holy places in Northern India. Considered God as an Ocean of Love and beauty. Teachings were based on the Upanishads and Bhagwad Gita. He had taught in the language of the common man. Soon a large number of people became his followers. Ramanand was his disciple He took his message to Northern parts of India. Ramananda He was the first reformer to preach in Hindi, the main language spoken by the people of the North. Educated at Benaras, lived in the 12 th Century A.D. Preached that there is nothing high or low. All men are equal in the eyes of God . He was an ardent worshipper of Rama Welcomed people of all castes and status to follow his teachings He had twelve chief disciples. One of them was a barber, another was a weaver, the third one was a cobbler and the other was the famous saint Kabir and the fifth one was a woman named Padmavathi. Considered God as a loving father. Kabir Disciple of Ramananda. It is said that he was the son of a Brahmin widow who had left him near a tank at Varanasi. A Muslim couple Niru and his wife who were weavers brought up the child . Later he became a weaver but he was attracted by the teachings of Swami Ramananda. -

Bhakti Movement

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

Visceral Politics of Food: the Bio-Moral Economy of Work- Lunch in Mumbai, India

Visceral politics of food: the bio-moral economy of work- lunch in Mumbai, India Ken Kuroda London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2018 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98896 words. 2 Abstract This Ph.D. examines how commuters in Mumbai, India, negotiate their sense of being and wellbeing through their engagements with food in the city. It focuses on the widespread practice of eating homemade lunches in the workplace, important for commuters to replenish mind and body with foods that embody their specific family backgrounds, in a society where religious, caste, class, and community markers comprise complex dietary regimes. Eating such charged substances in the office canteen was essential in reproducing selfhood and social distinction within Mumbai’s cosmopolitan environment. -

Hindurao S. Waydande Name: Dr. SAN Inamdar Permanent Address

Name: Prof. (Dr.) Hindurao S. Waydande Name: Dr. S. A. N. Inamdar Permanent Address: 2160, ‘Tahir’, Guruwar Peth, Miraj-416 410, Dist. - Sangli. Contact No. - 9423269272 Batch: B.Lib.&I.Sc, Department of Batch: M.Lib.&I.Sc.(1991),Department of Library & Information Science, Shivaji Library & Information Science, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. University, Kolhapur. Position/Achievements: 1] Professor & Position/Achievements: 1] Former Librarian, Head, Department of Library & Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli. 2] Worked as Vice President of “Maharashtra Information Science, Shivaji University, th th State Technical Library Association” since Kolhapur from 17 June 2006 to 19 Oct. 2003. 2008. 3] worked as a member of IQAC Committee 2] Assistant Librarian, Indian Institute of of G.A. College of Commerce, Sangli since Technology (IIT), Pawai, Mumbai. 2010. 3] Deputy Librarian (Rtd.), Indian Institute 4] Former Vice-President, Maharashtra State of Technology (IIT), Pawai, Mumbai. Technical Education Librarians Association. 5] worked as “National Advisor” at Help Desk Librarian Website. 6] He was awarded by “Jeevan Gaurav Purskar” by Maharashtra Foundation, Solapur in 2017. Name: Dr. M. G. Shinde Name: Dr. M. N. Jadhav Permanent Address: A/P – Warananagar, Staff Quarter 2/1, Office Address: Y.C. Warana Mahavidyalaya, Central Library, IIT Madras, Chennai -600036. Warananagar, Tal. – Panhala, Contact No. - 044-22574962 Dist. – Kolhapur – 416113. Contact No. - 8805783655 Batch: Ph.D. (2007), Department of Batch: Ph.D. (2013), Department of Library & Library & Information Science, Shivaji Information Science, Shivaji University, University, Kolhapur. Kolhapur. Position/Achievements: 1] Librarian, Position/Achievements: 1] Librarian, Central Yashwantrao Chavan Warana Library, IIT Madras, Chennai (March 2016 – Mahavidyalaya, Warnanagar. ( From 25- Present) 06-1993 to Present) 2] Deputy Librarian, Central Library, IIT 2] M.Phil. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 3

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) blank DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 3 First Edition Compiled by VASANT MOON Second Edition by Prof. Hari Narake Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 3 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : 14 April, 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. -

The Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics

THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS (Organ of the Indian Society of Agricultural Economics) Vol. I October 1946 1-• No. 2. CONFERENCE NUMBER PROCEEDINGS of the SIXTH CONFERENCE held at Benares, December, 1945. SUBJECTS I. T.V.A. Approach and its possibilities in Indian Agriculture. 2. Social Factors in Rural Economy. 3. Costs In relation to size of Farms. 4. Indian Food Policy. Rs. 3/- per copy. 12/- per annum. ••• THE INDIAN SOCIETY OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS BOMBAY: AIMS AND OBJECTS Tiaiii-Ote the inv-eitigation,--gtiiity *and inipieVemerit Of the economic . and social COnditions of agriculture and. rural life through (a) periodical conferences for the discussion of problems; (b) the publication of papers, or collectively; or in a periodical which may be issued under the auspices of the Society; n (c) co-operation with other institution having similar objects, such as the International Conference of Agricultural Economists and the Indian Economic Association; etc. EDITORIAL BOARD - Sir Manila! B. Nanavati V. L. Mehta 'D. R. Gadgil Gyan Chand L. C. Jain K. C. Ramkrislinan B,. K.Madan. - S. Kartar Singh •• - J. J. Anjaria (Managing Editor) Correspondence -relating to the supply- of copies should be addressed to the Honorary Secretary, The Indian Society. of Agricultural :Economies,- Esplanade Mansions, 3rd Floor,- Mahatma Gandhi Road,'Fort, Bombay. CONTENTS Pages Notes • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 Inaugural Address—Mr. Noel Hall • • .. • • • • 6 Welcome Address—Shri Sampurnanand .. • • • • • • 20 Presidential Address—Sir Manilal B. Nanavati • • • • • • 26 PAPERS AND DISCUSSION T. V. A. Approach and its possibilities in Indian Agriculture:— (1) S. Kesava Iyengar .. .. .. • • • • 39 (2) J. P. Bhattacharjee • • • • .. 44 (3) Gyan Chand • • • • • • • • • • . -

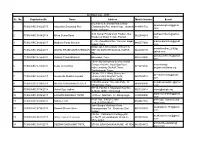

Architect List - 2019 Sr

Architect List - 2019 Sr. No. RegistrationNo Name Address Mobile Number E-mail 642,Flat no 9, Snehal Park,Behind splusadesigners@gmail. 1 PCMC/ARC/0652/2017 Adityasinh Dayanand Patil Chandrakant Patil Heart Hosp. Jawahar 8149991732 com Nagar, Kolhapur. A/16 Kumar Priydarshan Pashan, Sus subhaarchitects@yahoo. 2 PCMC/ARC/0438/2018 Milind Subha Saraf 9822554283 Road,near Balaji Temple Pashan com C - 16, Jivandhara Soc. Yamuna nagar, madhuraarchitect@gmail. 3 PCMC/ARC/0692/2017 Madhura Parag Merukar 9860577999 Nigadi- Pune com SHOP NO 1,SHIVANJALI HEIGHTS anandkhedkar_2000@ 4 PCMC/ARC/0562/2017 ANAND PRABHAKAR KHEDKAR BEHIND BORATE SANKUL KARVE 9822400439 yahoo.com RD. sucratuarchitects@gmail. 5 PCMC/ARC/0725/2018 Siddesh Pravin Bhansali Bibvewadi, Pune. 9028783400 com 1901/1902 Drewberry Everest World Complex Kolshet Road,Opp Bayer kedar.bhat@ 6 PCMC/ARC/0768/2018 Kedar Arvind Bhat 9819519195 India Company Dhokali,Thane, srujanconsultants.org Sandozbaugh Thane. Flat no. 102 J- Wing, Survey no directionnextds@gmail. 7 PCMC/ARC/0682/2017 Amannulla Shabbir Inamdar 5A/2A,212B/2, Mayfair Pacific, 9657009789 com Kondhawa Khurd Pune,NIBM C/O-AR.Laxman Thite Sita Park, 18, milind.laxmanthite@gmail 8 PCMC/ARC/0399/2018 MILIND RAMCHANDRA PATIL 8408880898 Shivajinagar, Pune .com RH 55, Flat No 8, Nityanand Hsg Soc, 9 PCMC/ARC/0718/2018 Vishal Vijay Jadhav 9923128414 [email protected] G-Block, MIDC, Chinchwad datta.laxmanthite@gmail. 10 PCMC/ARC/0532/2017 LAXMAN SADASHIV THITE 1st Floor, Sita Park, 18, Shivajinagar, 8408880890 com PLOT NO - 390,SECTOR archetype_associates@ 11 PCMC/ARC/0074/2017 Nafisa A Kazi 9922007885 27/A,PCNTDA,NIGDI gmail.com Janiv Bangla Malshiras Road swapnilgirme173@gmail. -

PRL. DISTRICT and SESSIONS JUDGE, VIJAYAPURA Hon. Sri

PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE, VIJAYAPURA Hon. Sri. SADANAND NARAYAN NAYAK PRL DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE Cause List Date: 05-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 11.00 AM to 02.00 PM 1 R.A. 92/2020 Bandagisab S/o. Papanna Pijnar I.S.Chimmalagi (L.C.R) Vs IA/1/2020 Yamanursab s/o. Papanna Pinjar IA/2/2020 2 R.A. 5/2017 Bapuray S/o Girimallappa Urgan A.S.Parit (CALL FOR LOWER Vs COURT RECORDS.) Irawwa W/o Balappa Urgan R.S.V. Cases listed below are adjourned due to Covid 19 3 E.A.T. 2/2015 21-12-2020 Sharanappa So Bhimappa S.N.Sollapatti (HEARING) Honamatti Vs N.S.Dhavalagi 4 O.S. 1/2017 21-12-2020 Shivagondappa S/o Sangappa Y.M.Anandshetti (HEARING) Gadigeppagoudr IA/2/2018 Vs IA/1/2017 Prasannakumari W/o Shashidhar IA/3/2018 Swamiji Hiremath 5 Misc 137/2019 22-12-2020 Padmavati W/o Sollapatti (HEARING) (11.00 AM to Channappagouda Patil R/o Srinivas 02.00 PM) Chikgarasangi Narayanrao. Vs Bhagirathibai Goudappagouda Patil since dead by LRs. 6 Misc 137/2018 22-12-2020 Srimad Channkeshav Devstan S.N.Kulkarni (HEARING) Trust Hiremannur R/by its Managing Trustee Hanamanthacharya K Agarkhed Vs NIL 7 Misc 125/2019 22-12-2020 The Gramantar Vidya Vardhak Indikar (HEARING) Sangh. Babaleshwar R/by its Mohammad General Secretary Rahim. Veeranagouda Biradar Vs Nil 8 Misc 356/2019 22-12-2020 Raghavendra S/o Venkatesh Jattkar Madhan (HEARING) Kulkarni President of Sri Krishnrao Lakshmi Narasimha Devastan Committee, Vs Nil 1/2 PRL. -

SIEMENS LIMITED List of Outstanding Warrants As on 18Th March, 2020 (Payment Date:- 14Th February, 2020) Sr No

SIEMENS LIMITED List of outstanding warrants as on 18th March, 2020 (Payment date:- 14th February, 2020) Sr No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A P RAJALAKSHMY A-6 VARUN I RAHEJA TOWNSHIP MALAD EAST MUMBAI 400097 A0004682 49.00 2 A RAJENDRAN B-4, KUMARAGURU FLATS 12, SIVAKAMIPURAM 4TH STREET, TIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 1203690000017100 56.00 3 A G MANJULA 619 J II BLOCK RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560010 A6000651 70.00 4 A GEORGE NO.35, SNEHA, 2ND CROSS, 2ND MAIN, CAMBRIDGE LAYOUT EXTENSION, ULSOOR, BANGALORE 560008 IN30023912036499 70.00 5 A GEORGE NO.263 MURPHY TOWN ULSOOR BANGALORE 560008 A6000604 70.00 6 A JAGADEESWARAN 37A TATABAD STREET NO 7 COIMBATORE COIMBATORE 641012 IN30108022118859 70.00 7 A PADMAJA G44 MADHURA NAGAR COLONY YOUSUFGUDA HYDERABAD 500037 A0005290 70.00 8 A RAJAGOPAL 260/4 10TH K M HOSUR ROAD BOMMANAHALLI BANGALORE 560068 A6000603 70.00 9 A G HARIKRISHNAN 'GOKULUM' 62 STJOHNS ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A6000410 140.00 10 A NARAYANASWAMY NO: 60 3RD CROSS CUBBON PET BANGALORE 560002 A6000582 140.00 11 A RAMESH KUMAR 10 VELLALAR STREET VALAYALKARA STREET KARUR 639001 IN30039413174239 140.00 12 A SUDHEENDHRA NO.68 5TH CROSS N.R.COLONY. BANGALORE 560019 A6000451 140.00 13 A THILAKACHAR NO.6275TH CROSS 1ST STAGE 2ND BLOCK BANASANKARI BANGALORE 560050 A6000418 140.00 14 A YUVARAJ # 18 5TH CROSS V G S LAYOUT EJIPURA BANGALORE 560047 A6000426 140.00 15 A KRISHNA MURTHY # 411 AMRUTH NAGAR ANDHRA MUNIAPPA LAYOUT CHELEKERE KALYAN NAGAR POST BANGALORE 560043 A6000358 210.00 16 A MANI NO 12 ANANDHI NILAYAM -

Sadhguru Calls for Concerted Action by All to Save World's Water Bodies

VOL 12 ISSUE 11 ● NEW YORK ● MARCH 23 - MARCH 29, 2018 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 www.theindianpanorama.news Facebook data breach: CEO Zuckerberg says it was a Sadhguru calls for concerted action ‘mistake’, ‘I’m sorry’ by all to save world’s water bodies Vows tougher security steps to restrict developers' access to such information UNITED NATIONS (TIP): Renowned spiritual leader Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev has welcomed the United Nations' initiative to launch a new decade to focus action on management of water resources, saying such effort is critical towards helping in the survival of future generations and calling Breaking his silence on for concerted action by all to save the world's the accusations of a water bodies. serious data breach, Sadhguru, speaking at a special event on Facebook CEO Mark Water, Sanitation and Women's Zuckerberg said "sorry" Empowerment during the current session of for the "mistake" Commission on the Status of Women here, on March 21, said it is "appropriate" that at SAN FRANCISCO (TIP): Facebook Inc chief executive this moment the UN has taken the step to Mark Zuckerberg apologized on Wednesday, March 21, for launch the 10 year action plan. "It is most Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev speaks at a Special Event on Water, Sanitation and mistakes his company made in how it handled data contd on page 32 Women's Empowerment during the current session of Commission on the Status of Women at the United Nations, March 21. Photo / Mohammed Jaffer-SnapsIndia belonging to 50 million of its users and promised tougher steps to restrict developers' access to such information. -

Novel Insights on Demographic History of Tribal and Caste Groups From

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Novel insights on demographic history of tribal and caste groups from West Maharashtra (India) using genome-wide data Guilherme Debortoli1,7, Cristina Abbatangelo1,7, Francisco Ceballos2,7, Cesar Fortes-Lima3, Heather L. Norton4, Shantanu Ozarkar5, Esteban J. Parra1 & Manjari Jonnalagadda6 ✉ The South Asian subcontinent is characterized by a complex history of human migrations and population interactions. In this study, we used genome-wide data to provide novel insights on the demographic history and population relationships of six Indo-European populations from the Indian State of West Maharashtra. The samples correspond to two castes (Deshastha Brahmins and Kunbi Marathas) and four tribal groups (Kokana, Warli, Bhil and Pawara). We show that tribal groups have had much smaller efective population sizes than castes, and that genetic drift has had a higher impact in tribal populations. We also show clear afnities between the Bhil and Pawara tribes, and to a lesser extent, between the Warli and Kokana tribes. Our comparisons with available modern and ancient DNA datasets from South Asia indicate that the Brahmin caste has higher Ancient Iranian and Steppe pastoralist contributions than the Kunbi Marathas caste. Additionally, in contrast to the two castes, tribal groups have very high Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI) contributions. Indo-European tribal groups tend to have higher Steppe contributions than Dravidian tribal groups, providing further support for the hypothesis that Steppe pastoralists were the source of Indo-European languages in South Asia, as well as Europe. Te South Asian subcontinent is characterized by a complex history of human migrations and interactions, as well as a variety of traditional practices, all of which have contributed to an extensive cultural and genetic diversity.