Lecture 3 & 4 Collated Readings Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

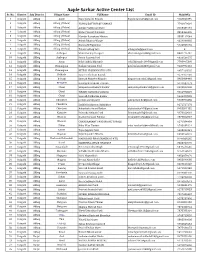

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

Police Station Wise Magistrate Raigad Alibag.Pdf

Police station wise Magisfiate 1. Alibag Police Station 2. Poynad Police Station 3. Revdanda Police Station Court of Chief Judicial Magistrate, Raigad 4. Mandawa Sagari Police Station 11 - Alibag 5. State Excise Depaftment Alibag & Flying Squad Police Station 6. Local Crime Branch 1. Alibag Police Station t2 Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Alibag 2. Poynad Police Station 3. Revdanda Police Station -tJ 2nd Jt. Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Alibag 4. Mandawa Sagari Police Station 3'd Jt. Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Alibag t4 5. State Excise Departrnent Alibag & Flying Squad Police Station l5 4sJt. Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Alibag 6. Local Crime Branch 1. Panvel Ciry Police Station t6 Jt. Civil Judge, Junior Divisioq Panvel 2. Panvel Town Police Station 1. Khandeshwar Police Stadon t7 2"d Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Panvel 2. NRI Sagari Police Station 1. Khargar Police Station 18 3'd Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Panvel 2. Navasheva Police Station 1. Kalamboli Police Station r9 4d Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Panvel 2. Kamothe Police Station 3. Taloia Police Station 1. Rasayani Police Station 2. State Excise Panvel City 3. State Excise Khalapur 4. State Excise Kadat 20 5d Civil Judge, J. D. & J.M.F.C., Panvel 5. State Excise Uran 6. State Excise Flying Squad No-2, Panvel 7. State Excise Flying Squad Thane 8. State Excise Flying Squad Mumbai L. Pen Police Station 2. Wadkhal Police Station 27 Civil Judge, J. -

The Study of Wetland Dolvi in Pen Taluka, Raigad, Maharashtra, India with Special Reference of Conservation

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 VOLUME 8, ISSUE 8(6), AUGUST 2019 THE STUDY OF WETLAND DOLVI IN PEN TALUKA, RAIGAD, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE OF CONSERVATION Dr.Sadanand B.Dharap Dr.Arun M. Patil PES Bhausaheb Nene College PES Bhausaheb Nene College Pen, Raigad,Maharashtra, India Pen, Raigad,Maharashtra, India Dr.Madhukar Salunke Sadanand.B.Chitnis PES Bhausaheb Nene College Assistant Professor Pen, Raigad,Maharashtra, India PES Bhausaheb Nene College Pen, Raigad,Maharashtra, India Mrs.Suniti S. Dharap Member - SEESCAP NGO Mahad, Maharashtra, India The topic under study is great concern for researchers because it directly related to the basic thing required for living on this planet, The WATER. The area i.e. pen taluka was taken for this as a part of government in initiative to study and find the exact environment in and around the wet lands in Maharshtra in general and specific in pen taluka. So they involved various NGO and expert from different fields for this study. The Pen taluka is typically located in outskirts of Mumbai and represent a typical example of urbanisation. The urbanisation always affects the environment first and then gives fruit of development. It deteriorates the ecosystems in that area. The first and foremost natural source which becomes vulnerable is water. We want to study this part and further to make aware the society is general for protection and conservation of the water recourses. Definition and introduction of wetlands:-There are many different types of wetlands. -

Chapter- IV PROFILE of RAIGAD DISTRICT 1) Historical Background

Chapter- IV PROFILE OF RAIGAD DISTRICT 1) Historical Background. 2) Geographical Location. 3) Topography. 4) Water Resources. 5) Climate. 6) Soil and Agriculture. 7) Irrigation. 8) Industries and Transport. 9) Population. 10) Educational Facility. 11) Highlights. 147 Chapter IV Profile of Raiqad District The research study deals with the management of Secondary Education in Raigad District. Hence, it is necessary to make a brief review of the growth of secondary education in the district after independence and the present scenario. At the same time it is also necessary to know the socio-economic position of the district which directly or indirectly influences the educational growth. The review covers general information in respect of historical background, geographical location, population, literacy, agriculture, Industry, educational progress and other related aspects. 1. Historical background. The present Raigad district has been named due to the historical fort ' Raigad ' in Maharashtra state. ' The earlier name ' Kulaba ' was changed to ' Raigad ' on 1®' may 1981 by the Maharashtra government*. The fort Raigad was the capital of ' Raje Shri Chhatrapati Shivaji ' during the 17'" century. The original name of the Raigad fort was ' Rairi ' . The fort Rairi was very lofty and an almost inaccessible plateau. ' Shri Chhatrapati Shivaji Raje Conquered Rairi fort from the More's of Jawali in 1656 '} He then repaired the fort and strengthened it. 'It was named Raigad and made the seat of his Kingdom in 1664'. ^ 148 It was believed that Kulaba port was one of the trading centers of Janjira State. At that time, probably the entire Kulaba coast was an important trading center of the Konkan region. -

Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report

KIHIM RESORT Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report M R . GAUTAM CHAND Project Proponent +91 98203 39444 [email protected] MOEFCC Proposal No.:IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 18 A p r i l , 2019 Project Proponent: Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report for CRZ MCZMA Ref. No.: Mr. Gautam Chand (Individual) Proposed Construction of Holiday Resort CRZ-2015/CR-167/TC-4 Village: Kihim, Taluka: Alibag, District: Raigad, MOEFCC Proposal No.: State: Maharashtra, PIN: 402208, Country: India IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 CONTENTS Annexure A from MOEFCC CRZ Meeting Agenda template 6 Compliance on Guidelines for Development of Beach Resorts or Hotels 10 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 13 1.1 Preamble 13 1.2 Objective and Scope of study 13 1.3 The Steps of EIA 13 1.4 Methodology adopted for EIA 14 1.5 Project Background 15 1.6 Structure of the EIA Report 19 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Description of the Site 20 2.3 Site Selection 21 2.4 Project Implementation and Cost 21 2.5 Perspective view 22 2.5.1 Area Statement 24 2.6 Basic Requirement of the Project 24 2.6.1 Land Requirement 24 2.6.2 Water Requirement 25 2.6.3 Fuel Requirement 26 2.6.4 Power Requirement 26 2.6.5 Construction / Building Material Requirement 29 2.7 Infrastructure Requirement related to Environmental Parameters 29 2.7.1 Waste water Treatment 29 2.7.1.1 Sewage Quantity 29 2.7.1.2 Sewage Treatment Plant 30 2.7.2 Rain Water Harvesting & Strom Water Drainage 30 2.7.3 Solid Waste Management 31 2.7.4 Fire Fighting 33 2.7.5 Landscape 33 2.7.6 Project Cost 33 CHAPTER 3: DESCRIPTION -

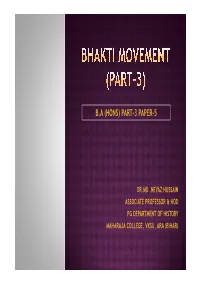

Bhakti Movement Part-3

B.A (HONS) PART-3 PAPER-5 DR.MD .NEYAZ HUSSAIN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR & HOD PG DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAHARAJA COLLEGE, VKSU, ARA (BIHAR) Ramanuja He was one of the earliest reformers. Born in the South, he made a pilgrimage to some of the holy places in Northern India. Considered God as an Ocean of Love and beauty. Teachings were based on the Upanishads and Bhagwad Gita. He had taught in the language of the common man. Soon a large number of people became his followers. Ramanand was his disciple He took his message to Northern parts of India. Ramananda He was the first reformer to preach in Hindi, the main language spoken by the people of the North. Educated at Benaras, lived in the 12 th Century A.D. Preached that there is nothing high or low. All men are equal in the eyes of God . He was an ardent worshipper of Rama Welcomed people of all castes and status to follow his teachings He had twelve chief disciples. One of them was a barber, another was a weaver, the third one was a cobbler and the other was the famous saint Kabir and the fifth one was a woman named Padmavathi. Considered God as a loving father. Kabir Disciple of Ramananda. It is said that he was the son of a Brahmin widow who had left him near a tank at Varanasi. A Muslim couple Niru and his wife who were weavers brought up the child . Later he became a weaver but he was attracted by the teachings of Swami Ramananda. -

Company List All for PDF.Xlsx

Annexure - A (Offline) order no.98 Dt. 24.3.2020 Sl. Name of Factory Location 1 Aarsha Chemical Pvt Ltd 2 AL Tamash Export Pvt Ltd Taloja MIDC 3 Alkem Laboratories Ltd Taloja MIDC 4 Alkyl Amines chemical Ltd Patalganga MIDC 5 Alkyl Amines chemical Ltd Patalganga MIDC 6 Allana Investment & Trading Co.Pvt.Ltd Taloja MIDC 7 Allana Investment & Trading Co.Pvt.Ltd Taloja MIDC 8 ALTA Laboratories Ltd Khopoli MIDC 9 ANEK Prayog P.Ltd Dhatav MIDC 10 Anshul Speciality Molecules Ltd Dhatav MIDC 11 Apcotex Industries Ltd Taloja MIDC 12 Aquapharm Chemicals Pvt.Ltd. Mahad MIDC 13 Archroma India Pvt Ltd Dhatav MIDC 14 Asahi India Glass Ltd Taloja MIDC 15 Ashok Alco Chem Limited Mahad MIDC 16 B E C Chemicals Pvt Ltd Dhatav MIDC 17 B.O.C. (i) LTD. Taloja MIDC 18 Bakul Aromatics & chemicals Ltd Patalganga MIDC 19 Bharat Electronics Ltd. (Govt of India UT) Taloja 20 Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. LPG BOT Uran 21 Bismillah Frozen Foods Exports Taloja MIDC 22 Blue Fin Frozen Foods Pvt Ltd Taloja MIDC 23 Bushra foods P.Ltd Taloja MIDC 24 Castelrock Fisheries Pvt Ltd Taloja MIDC 25 Champion Steel Industries Ltd (Permission Canceled) Taloja MIDC 26 Cipla Limited Palalganga MIDC 27 Cipla Limited Palalganga MIDC 28 Classic Frozen Foods P.Ltd Taloja MIDC 29 Cold Star Logistics Pvt Ltd Panvel 30 Danashmand Organics Pvt Ltd Dhatav MIDC 31 Deepak Fertilizers & Petrochemicals co. Taloja MIDC 32 Deepak Fertilizers & Petrochemicals co. Taloja MIDC 33 Deepak Nitrite Ltd Taloja MIDC 34 Deepak Nitrite Ltd (APL DIVN) Roha MIDC 35 Delilghtful Foods P.Ltd Taloja MIDC 36 Dolphin Marine Foods & Processors (I) Taloja MIDC 37 Doshi Slitters P.Ltd Taloja MIDC 38 Dow Chemical Ltd Taloja MIDC 39 Elaf Cold Storage Taloja MIDC 40 Elppe Chemicals Pvt Ltd Dhatav MIDC 41 Embio Limited Mahad MIDC 42 Empire Foods Taloja MIDC E:\Corona 23-3-2020 Night\company list All for PDF Page 1 Sl. -

Self Study Report

MANGAON TALUKA EDUCATION SOCIETYS’S DOSHI VAKIL ARTS & Goregaon Co – Operative Urban Bank Science & Commerce College GOREGAON – RAIGAD. (402 103) Est. 1998 (Affiliated to Mumbai University) Ph. (02140) 250348 Shri. Ramanlal Narayan Sheth Dr. G.D.Giri Shri. Dilip Nathuram Sheth President Principal Chairman To, The Director, National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), P.O. Box. 1075, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore – 560 072, Karnataka (India) Subject: Submission of Self Study Report. Dear Sir, We take this opportunity to submit our Self Study Report to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) for assessment and accreditation. This Self Study Report is prepared by us with honesty and sincere efforts as per the directive guidelines formulated by NAAC. In this report, we have highlighted our strengths and achievements in which we have succeeded within the last five years of our college. It is a privilege and matter of great pride for us to get accredited by an esteemed body like NAAC. NAAC as an autonomous body has proved as a noble assessment institution in maintaining quality excellence in the field of higher education of India for the last 20 years. Hope that our Self Study Report will satisfy your requirements and expectations. We will be grateful to you if you convey your useful suggestions. Thank you. Sincerely yours Sd/- Dr. G. D. Giri For Reference 1. Email ID : [email protected] 2. Website : www.dvcgoregaon.edu.in 3. Track ID : MHCOGN23059 Encl. : 1. 5 copies (with CDs) of SSR. 2. LOI of the college dated, 12 Nov. 2014. 3. Your letter No. NAAC/WR/GH/MHCOGN23059/ 1st cycle/2014-15 dated 27 March 2015. -

Bhakti Movement

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

Directorate of Vocational Education and Training, Maharashtra State Trade Directory for Admission in Year 2021-22

Directorate of Vocational Education and Training, Maharashtra State Trade Directory for Admission in Year 2021-22 Trade Name : Architectural Draughtsman Region : MUMBAI ITI NAME TALUKA DISTRICT REGION INTAKE GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, MUMBAI-11, MUMBAI CITY MUMBAI CITY MUMBAI 24 TAL: MUMBAI, DIST: MUMBAI SHAHAR Total Seats for Admission 2021 24 All Trade and Unit Proposed by Regional Office, MUMBAI Page 1 of 80 This is Indicative Directory released on 20th July 2021. Directorate of Vocational Education and Training, Maharashtra State Trade Directory for Admission in Year 2021-22 Trade Name : Attendant Operator (Chemical Plant) Region : MUMBAI ITI NAME TALUKA DISTRICT REGION INTAKE GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, MAHAD, TAL: MAHAD RAIGARH MUMBAI 48 MAHAD, DIST: RAIGAD GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NAGOTHANE, ROHA RAIGARH MUMBAI 24 TAL: ROHA, DIST: RAIGAD GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, CHIPLUN, TAL: CHIPLUN RATNAGIRI MUMBAI 48 CHIPLUN, DIST: RATNAGIRI GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, AMBERNATH, AMBARNATH THANE MUMBAI 24 TAL: AMBERNATH, DIST: THANE Total Seats for Admission 2021 144 All Trade and Unit Proposed by Regional Office, MUMBAI Page 2 of 80 This is Indicative Directory released on 20th July 2021. Directorate of Vocational Education and Training, Maharashtra State Trade Directory for Admission in Year 2021-22 Trade Name : Basic Cosmetology Region : MUMBAI ITI NAME TALUKA DISTRICT REGION INTAKE GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, (WOMAN), MUMBAI CITY MUMBAI CITY MUMBAI -

Visceral Politics of Food: the Bio-Moral Economy of Work- Lunch in Mumbai, India

Visceral politics of food: the bio-moral economy of work- lunch in Mumbai, India Ken Kuroda London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2018 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98896 words. 2 Abstract This Ph.D. examines how commuters in Mumbai, India, negotiate their sense of being and wellbeing through their engagements with food in the city. It focuses on the widespread practice of eating homemade lunches in the workplace, important for commuters to replenish mind and body with foods that embody their specific family backgrounds, in a society where religious, caste, class, and community markers comprise complex dietary regimes. Eating such charged substances in the office canteen was essential in reproducing selfhood and social distinction within Mumbai’s cosmopolitan environment.