Data Sheet on Gymnosporangium Globosum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol. VI - Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A. Bonet and G. Carrión INTRODUCTION TO NEOTROPICAL ENTOMOLOGY AND PHYTOPATHOLOGY A. Bonet Department of Entomology, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico G. Carrión Department of Biodiversity and Systematic, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico Keywords: Biodiversity loss, biological control, evolution, hotspot regions, insect biodiversity, insect pests, multitrophic interactions, parasite-host relationship, pathogens, pollination, rust fungi Contents 1. Introduction 2. History 2.1. Phytopathology 2.1.1. Evolution of the Parasite-Host Relationship 2.1.2. The Evolution of Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Host Plants 2.1.3. Flor’s Gene-For-Gene Theory 2.1.4. Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Plant Parasitic Fungi and Hyperparasites 2.2. Entomology 2.2.1. Entomology in Asia and the Middle East 2.2.2. Entomology in Ancient Greece and Rome 2.2.3. New World Prehispanic Cultures 3. Insect evolution 4. Biodiversity 4.1. Biodiversity Loss and Insect Conservation 5. Ecosystem services and the use of biodiversity 5.1. Pollination in Tropical Ecosystems 5.2. Biological Control of Fungi and Insects 6. The future of Entomology and phytopathology 7. Entomology and phytopathology section’s content 8. ConclusionUNESCO – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchesSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Insects are among the most abundant and diverse organisms in terrestrial ecosystems, making up more than half of the earth’s biodiversity. To date, 1.5 million species of organisms have been recorded, although around 85% of potential species (some 10 million) have not yet been identified. In the case of the Neotropics, although insects are clearly a vital element, there are many families of organisms and regions that are yet to be well researched. -

The Pathogenicity and Seasonal Development of Gymnosporangium

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1931 The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa Donald E. Bliss Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Botany Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Bliss, Donald E., "The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa " (1931). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Pear Trellis Rust

Dr. Yonghao Li Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PEAR TRELLIS RUST Pear trellis rust (European pear rust) is one premature defoliation, significant diebacks, of most devastating diseases on fruit and and reduced tree vigour (Figure 1). ornamental pear trees in Europe. In the United States, since the disease was first SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTICS reported in the Bellingham, WA in 1997, it The disease affects pear and juniper plants, has moved from the west coast to east coast. which is the alternate host of the fungal In Connecticut, pear trellis rust was first pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae. On reported in 2012. Although the disease is pear trees, the disease mainly damages considered cosmetic on pear trees, heavy and leaves although twigs and fruit can also be repeated infections due to wet spring infected. The initial symptom appears as weather conditions may result in severe yellow spots on the upper side of young leaves in the spring. Lesions become reddish orange in color and expand up to 3/4 inch in diameter (Figure 2). By mid summer, small black dots (spermagonia) form in the center of the spot on the upper side of leaves. And then, light brown, Figure 1. Browning of leaves and early Figure 2. Reddish-brown lesions on the defoliation of heavily infected pear trees in upper- (left) and lower-side (right) of the early summer leaf acorn-shaped structures (aecia) form on the differences in susceptibility between under side of the leaf directly below the varieties. -

Master Thesis

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Uppsala 2011 Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Iuliia Kyiashchenko Master‟ thesis, 30 hec Ecology Master‟s programme SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Iuliia Kyiashchenko Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Uppsala 2011 Supervisors: Prof. Jonathan Yuen, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Anna Berlin, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Examiner: Anders Dahlberg, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Credits: 30 hp Level: E Subject: Biology Course title: Independent project in Biology Course code: EX0565 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key words: rust fungi, aecia, aeciospores, morphology, barberry, DNA sequence analysis, phylogenetic analysis Front-page picture: Barberry bush infected by Puccinia spp., outside Trosa, Sweden. Photo: Anna Berlin 2 3 Content 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 6 1.1 Life cycle…………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.2 Hyphae and haustoria………………………………………………………………... 9 1.3 Rust taxonomy……………………………………………………………………….. 10 1.3.1 Formae specialis………………………………………………………………. 10 1.4 Economic importance………………………………………………………………... 10 2 Materials and methods……………………………………………………………... 13 2.1 Rust and barberry -

Basidiomycota

BASIDIOMYCOTA 1. Class Uredinoiomycetes –Order Uredinales - The Rusts 2. Class Ustomycetes -Order Ustilaginales - The Smuts 3. Class Basidiomycetes- Order Agaricales - the boletes, gilled mushrooms - inky caps, oyster mushrooms, etc. Gilled mushrooms Inky caps The Rusts These are obligate parasites. Generally these require two host to complete their lifecycle. Primary hosts – the host on which basidia and basidiospores are produced. Alternate host – the other host in the life cycle on which spermagonia and aecia are produced. Alternative host – the host that a pathogen can infect in place of the primary or alternate hosts. Heteroecious – organisms with a primary and alternate host. Autoecious – organisms that have only a single (primary) host. Macrocyclic rust – long cycle rust. Produce all 5 spore types. Demicyclic rust – medium cycle rust. Omits uredia. Microcyclic rust – short cycle rusts. Produces basidiospores, teliospores and spermatia. Stem Rust of Wheat caused by Puccinia graminis Reduces yield and quality of grain fungus causes lesions or pustules on wheat stems. Management . remove alternate host (i.e., barberry); . use resistant cultivars of wheat Cedar-Apple Rust caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Apples become deformed and ugly; fruit size reduced due to damage to foliage – Management . removal of cedar trees, which serves as the alternate host; . spray apple trees with fungicides, and . use rust-resistant apple trees The Smuts Corn smut caused by Ustilago maydis Galls develop on male and female (ear) inflorescences. No major methods of control recommended; tends to be a chronic but relatively insignificant disease. Loose smut of cereals by Ustilago avenae, U. nuda, and U. tritici Flowering parts of plants develop spore-filled galls (teliospores) – infected seed treated with fungicides before planting; use of certified smut-free seeds and systemic fungicides; hot-water treatment of seed to kill fungus. -

Cedar Apple Rust

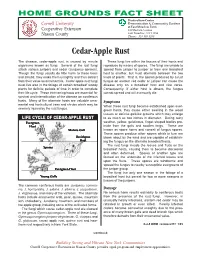

HOME GROUNDS FACT SHEET Horticulture Center Cornell University Demonstration & Community Gardens at East Meadow Farm Cooperative Extension 832 Merrick Avenue East Meadow, NY 11554 Nassau County Phone: 516-565-5265 Cedar-Apple Rust The disease, cedar-apple rust, is caused by minute These fungi live within the tissues of their hosts and organisms known as fungi. Several of the rust fungi reproduce by means of spores. The fungi are unable to attack various junipers and cedar (Juniperus species). spread from juniper to juniper or from one broadleaf Though the fungi usually do little harm to these trees host to another, but must alternate between the two and shrubs, they make them unsightly and thus detract kinds of plants. That is, the spores produced by a rust from their value as ornamentals. Cedar-apple rust fungi fungus on eastern red cedar or juniper can cause the must live also in the foliage of certain broadleaf woody disease only on a broadleaf host and vice versa. plants for definite periods of time in order to complete Consequently, if either host is absent, the fungus their life cycle. These intervening hosts are essential for cannot spread and will eventually die. survival and intensification of the disease on coniferous hosts. Many of the alternate hosts are valuable orna- Symptoms mental and horticultural trees and shrubs which may be When these rust fungi become established upon ever- severely injured by the rust fungus. green hosts, they cause either swelling in the wood tissues or definite gall-like growths which may enlarge LIFE CYCLE OF CEDAR-APPLE RUST to as much as two inches in diameter. -

Crataegus (Hawthorn)

nysipm.cornell.edu 2019 Search for this title at the NYSIPM Publications collection: ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/41246 Disease and Insect Resistant Ornamental Plants Mary Thurn, Elizabeth Lamb, and Brian Eshenaur New York State Integrated Pest Management Program, Cornell University CRATAEGUS Hawthorn pixabay.com Crataegus is a large genus of shrubs and small trees in the rose family commonly known as hawthorn. This popular ornamental has showy pink or white flowers in spring and colorful berry-like fruit. Some species also have long thorns that provide protection for wildlife but may be a hazard in the landscape–thornless cultivars are available. Like other rosaceous plants, hawthorns are sus- ceptible to a number of diseases including fire blight, scab, leaf spot and several types of rust. Insect pests include lace bugs and leaf miners. DISEASES Cedar Rust diseases on hawthorn, which include hawthorn rust and quince rust, are caused by sev- eral fungi in the genus Gymnosporangium that spend part of their life cycle on Eastern red cedar (Juni- perus virginiana) and other susceptible junipers, and another part of their life cycle on plants in the rose family, especially Malus and Crataegus. Since two hosts are required for these fungi to complete their life cycle, one way to reduce disease problems is to avoid planting alternate hosts near each other. Hawthorn Rust, caused by Gymnosporangium globosum, is a significant concern for Crataegus spp. in the Northeast (7). Hawthorns are the main broadleaved host for this rust, and yellow-orange leaf spots are the most common symptom. (8). With severe infections, foliage may turn bright yellow and drop prematurely (15). -

Diagnosing Those Dang Diseases

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Diagnosing Those Dang Diseases Erik Draper, Commercial Horticulture The Ohio State University Extension- Geauga County What is Plant Pathology From Greek: pathos = suffering Logos = to study Pathology literally means “the study of suffering” Therefore plant pathology is literally the study of plant suffering or diseases of plants! Pathology Changed the World… Irish Potato Famine…1845… Late Blight…1.5 million people killed… Irish dispersed Downy Mildew of Grape…19th century (1878) accident…destroyed almost all vineyards in France, Germany, and Italy Salem Witch Trials…Ergot of rye…”Stark raving mad” in Medieval times also Chestnut blight…NYC-1904… wiped out most American chestnut trees…major lumber source Pathology Changed the World… Dutch Elm Disease…1930’s eliminated millions of mature American elm in continental US Italian Tomato Famine… spread pizza and spaghetti to save the rest of the world on Fridays Sudden Oak Death…first discovered in Mill Valley, California 1995… not properly identified until 2000 as Phytophthora ramorum… killing oaks, tanoaks and over 100 susceptible host species In horticulture, as in medicine, treatment of plant symptoms/problems without correct diagnosis… is MALPRACTICE! -Alan Siewert, ODNR Forester ‘SHROOMS ‘SHROOMS 2006- Full of Fungi HUMMM…WHY? Fungi Require Moisture High Humidity Heavy Dews Fog or Mists Intermittent Rains Cloudy & Overcast Plant Disease Defined… “A malfunctioning of host cells and tissues that results from their continuous irritation by a pathogenic agent or environmental factor and leads to the development of symptoms. Disease is a condition involving abnormal changes in the form, physiology, integrity or behavior of a plant. -

Gymnosporangium Sabinae) in Austria and Implications for Possible Control Strategies 1 1 2 M

Reviewed Papers 65 Monitoring of pear rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) in Austria and implications for possible control strategies 1 1 2 M. Filipp , A. Spornberger and B. Schildberger Abstract In recent years pear rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) caused serious damages in organically managed pear orchards, on different sites in Eastern Austria, especially in the surroundings of St. Pölten. Therefore the appearance and development of the fungus was monitored over three years 2009-2011 in this area. The infection period and phase of spore discharge were estimated with a spore trap and with observations of symptoms on potted pear seedlings. The results of this monitoring campaign showed a moderate infestation level in pear orchards over the three years with low damage on fruits. In all three years, the main infection period was found to be from end of April to early May. Light infections were observed also from mid of April until the end of May. Later spores were flying until mid of June but did not lead to infections. In an organically managed orchard a reduction of the infestation dependent on the distance to an infected host plant and on treatments with fungicides used in organic growing could be found. Keywords: pear rust, Gymnosporangium sabinae, organic farming. Introduction In 2007 and especially in 2008, pear rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) caused severe damage on leaves, fruits and twigs of pears in many orchards in the area of St. Pölten. In this area most of the organically managed pear orchards in Austria were planted during the last 8 years. G. sabinae is a host changing fungus which is overwintering on twigs of some cedar species (Juniperus sabina, J. -

Gymnosporangium Rust Management

Under the Scope: Gymnosporangium Rust Management We oen receive calls from homeowners requesng specific fungicide recommendaons and ming for managing the Cedar‐Apple Rust fungus or other closely related Gymnosporangium spp. that infect junipers and rosaceous hosts. You may find that there are many internet fact sheets on Cedar‐apple rust, (including our own) or other common Gymnosporangium rusts such as quince or hawthorn rust, and you may note that any given fact sheet may provide a specific fungicide recommendaon for treatment of one of these rusts and may even provide a general treatment me. Please keep in mind however that those recommendaons were likely made for the best me to manage that pest in that state! If your site is elsewhere, and you follow that recommendaon, you may get lile or no control and may waste an enre season treang at the wrong me. Galls of various species and stages of development on juniper. First provided by S. Jensen; remaining photos provided by D. Dailey O’Brien Managing Gymnosporangium rusts can be much more complicated than managing other disease issues for a couple of reasons. Each Gymnosporangium sp. has two unrelated hosts that the fungus requires to complete it’s life cycle. Spores produced on one host do not re‐infect that host, they infect the alternate host. So, when you want to treat your Juniper (or Eastern red cedar) to protect it, you need to treat when the alternate host (quince, pear, crabapple, etc.) is producing infecous spores, and vice versa. Timing of treatment also depends on the locaon of the trees! Treatment of a crabapple in Georgia on the same calendar date as treatment of a crabapple in New York is not likely to provide good results for both as sporulaon on the Juniper in those locaons is unlikely to occur on the same calendar date. -

G. Monticola and G. Unicorne

Mycologia, 101 (6), 2009, pp. 790-809. DOl: 10.3852/08-221 2009 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence. KS 66044-8897 The rust fungus Gymnosporangium in Korea including two new species, G. monticola and G. unicorne Hye Young Yunt molecular as well as morphological characteristics. Department of Forest Sciences, College of Agri culture Analyses of phenotypic characters mapped onto the and I,j?' Sciences, .Seou1 National University, 56-1 Sin/i, tn-doug, Kwanak-gu, Seoul 151-921, phylogenetic tree show that teliospore length followed Republic of Korea by telia shape and telia length are conserved; these are morphological characters useful in differentiating Honga Soon Gyu species of G'vmno.c/.sorartgiurn. Each of the nine species Biolog-icai Resource Center, Korea Institute of Bioscience of Cymnosporar glum in Korea is described and illus- and Biotechnology, 52 Own-dong, Yusong-kn, Daejeon 305-806, Republic '?f Korea trated, and keys based on aecia and telia stages are provided. l.ectotype specimens for several names Amy Y. Rossman described iii Gymnosporangium are designated. Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, Key words: aecia stage, forest pathogens, LSU Agricultural Research Service, Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, Ma?yland 20705 rDNA, Piiccinialcs, systematics, lelia stage Seung Kyu Lee INTRODUCTION Southern. Forest Research Center, Korea Forest Research Institute, 719-1 Gazwa-dong, Jinju City The rust fungi (Pucciniales) are important plant Kyungsangnam-Do, 660-300, Republic of Korea pathogens affecting a variety of angiosperins and Kvung Joori Lee gymnosperms, potentially causing severe damage to Department of Forest Sciences, College of Agriculture agricultural crops and forest trees (Scott and Chakra- and Life Sciences, Seoul Vational University, 564 vorty 1982, Swann ci.