Gymnosporangium Sabinae) in Austria and Implications for Possible Control Strategies 1 1 2 M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol. VI - Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A. Bonet and G. Carrión INTRODUCTION TO NEOTROPICAL ENTOMOLOGY AND PHYTOPATHOLOGY A. Bonet Department of Entomology, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico G. Carrión Department of Biodiversity and Systematic, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico Keywords: Biodiversity loss, biological control, evolution, hotspot regions, insect biodiversity, insect pests, multitrophic interactions, parasite-host relationship, pathogens, pollination, rust fungi Contents 1. Introduction 2. History 2.1. Phytopathology 2.1.1. Evolution of the Parasite-Host Relationship 2.1.2. The Evolution of Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Host Plants 2.1.3. Flor’s Gene-For-Gene Theory 2.1.4. Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Plant Parasitic Fungi and Hyperparasites 2.2. Entomology 2.2.1. Entomology in Asia and the Middle East 2.2.2. Entomology in Ancient Greece and Rome 2.2.3. New World Prehispanic Cultures 3. Insect evolution 4. Biodiversity 4.1. Biodiversity Loss and Insect Conservation 5. Ecosystem services and the use of biodiversity 5.1. Pollination in Tropical Ecosystems 5.2. Biological Control of Fungi and Insects 6. The future of Entomology and phytopathology 7. Entomology and phytopathology section’s content 8. ConclusionUNESCO – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchesSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Insects are among the most abundant and diverse organisms in terrestrial ecosystems, making up more than half of the earth’s biodiversity. To date, 1.5 million species of organisms have been recorded, although around 85% of potential species (some 10 million) have not yet been identified. In the case of the Neotropics, although insects are clearly a vital element, there are many families of organisms and regions that are yet to be well researched. -

The Pathogenicity and Seasonal Development of Gymnosporangium

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1931 The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa Donald E. Bliss Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Botany Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Bliss, Donald E., "The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa " (1931). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Pear Trellis Rust

Dr. Yonghao Li Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PEAR TRELLIS RUST Pear trellis rust (European pear rust) is one premature defoliation, significant diebacks, of most devastating diseases on fruit and and reduced tree vigour (Figure 1). ornamental pear trees in Europe. In the United States, since the disease was first SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTICS reported in the Bellingham, WA in 1997, it The disease affects pear and juniper plants, has moved from the west coast to east coast. which is the alternate host of the fungal In Connecticut, pear trellis rust was first pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae. On reported in 2012. Although the disease is pear trees, the disease mainly damages considered cosmetic on pear trees, heavy and leaves although twigs and fruit can also be repeated infections due to wet spring infected. The initial symptom appears as weather conditions may result in severe yellow spots on the upper side of young leaves in the spring. Lesions become reddish orange in color and expand up to 3/4 inch in diameter (Figure 2). By mid summer, small black dots (spermagonia) form in the center of the spot on the upper side of leaves. And then, light brown, Figure 1. Browning of leaves and early Figure 2. Reddish-brown lesions on the defoliation of heavily infected pear trees in upper- (left) and lower-side (right) of the early summer leaf acorn-shaped structures (aecia) form on the differences in susceptibility between under side of the leaf directly below the varieties. -

Pear Tree Trellis Rust.Pdf

www.landscape.org The Plant Doctor’s CONCOLOR FIR & RHIZOSPHAERALANDSCAPE NEEDLECAST TIPS By David L. Roberts, Ph.D., Senior Academic Specialist, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Michigan State University TRELLIS RUST: A MANAGEMENT UPDATE Photo 2 Photo 2: This photo of the same three trees was taken Photo 1 approximately one year later in 2016. It shows that the trees have rebounded somewhat. These three trees were injected Photo 1: This photo of TR was taken in July of 2015. The with Shepherd by Arborsystems Wedgle in the early spring of severe debilitating effects of the disease are readily visible 2016. While this may be anecdotal, there is evidence that se- and have resulted in apparent decline of the trees. verely declined trees may exhibit some recovery. Obviously, it would be better to prevent severe decline from happening in the first place if we want to maintain relatively healthy pear INTRODUCTION: trees in the landscape; we might be able to accomplish this Trellis Rust (aka European Pear Rust), caused by the fungus with reasonable management steps. Gymnosporangium sabinae (=Gymnosprangium fuscan), has spread throughout Southeast Michigan. Originally from Europe, the disease may represent a serious health threat to Pyrus species, both ornamental and fruit pear types. Symptoms and the disease cycle were summarized in two previous Landsculptor articles: September 2014 and September 2015 issues. The disease will likely advance across Michigan in the next few years. We have little experience with the control of Trellis Rust, but through observations over the last couple of years combined with our knowledge of similar diseases, I believe I can provide some practical measures that arborists/ landscapers may consider in their management plans. -

Master Thesis

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Uppsala 2011 Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Iuliia Kyiashchenko Master‟ thesis, 30 hec Ecology Master‟s programme SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Iuliia Kyiashchenko Taxonomic and phylogenetic study of rust fungi forming aecia on Berberis spp. in Sweden Uppsala 2011 Supervisors: Prof. Jonathan Yuen, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Anna Berlin, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Examiner: Anders Dahlberg, Dept. of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology Credits: 30 hp Level: E Subject: Biology Course title: Independent project in Biology Course code: EX0565 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key words: rust fungi, aecia, aeciospores, morphology, barberry, DNA sequence analysis, phylogenetic analysis Front-page picture: Barberry bush infected by Puccinia spp., outside Trosa, Sweden. Photo: Anna Berlin 2 3 Content 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 6 1.1 Life cycle…………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.2 Hyphae and haustoria………………………………………………………………... 9 1.3 Rust taxonomy……………………………………………………………………….. 10 1.3.1 Formae specialis………………………………………………………………. 10 1.4 Economic importance………………………………………………………………... 10 2 Materials and methods……………………………………………………………... 13 2.1 Rust and barberry -

Basidiomycota

BASIDIOMYCOTA 1. Class Uredinoiomycetes –Order Uredinales - The Rusts 2. Class Ustomycetes -Order Ustilaginales - The Smuts 3. Class Basidiomycetes- Order Agaricales - the boletes, gilled mushrooms - inky caps, oyster mushrooms, etc. Gilled mushrooms Inky caps The Rusts These are obligate parasites. Generally these require two host to complete their lifecycle. Primary hosts – the host on which basidia and basidiospores are produced. Alternate host – the other host in the life cycle on which spermagonia and aecia are produced. Alternative host – the host that a pathogen can infect in place of the primary or alternate hosts. Heteroecious – organisms with a primary and alternate host. Autoecious – organisms that have only a single (primary) host. Macrocyclic rust – long cycle rust. Produce all 5 spore types. Demicyclic rust – medium cycle rust. Omits uredia. Microcyclic rust – short cycle rusts. Produces basidiospores, teliospores and spermatia. Stem Rust of Wheat caused by Puccinia graminis Reduces yield and quality of grain fungus causes lesions or pustules on wheat stems. Management . remove alternate host (i.e., barberry); . use resistant cultivars of wheat Cedar-Apple Rust caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Apples become deformed and ugly; fruit size reduced due to damage to foliage – Management . removal of cedar trees, which serves as the alternate host; . spray apple trees with fungicides, and . use rust-resistant apple trees The Smuts Corn smut caused by Ustilago maydis Galls develop on male and female (ear) inflorescences. No major methods of control recommended; tends to be a chronic but relatively insignificant disease. Loose smut of cereals by Ustilago avenae, U. nuda, and U. tritici Flowering parts of plants develop spore-filled galls (teliospores) – infected seed treated with fungicides before planting; use of certified smut-free seeds and systemic fungicides; hot-water treatment of seed to kill fungus. -

Differences in Leaf Morphological Parameters of Pear

plants Article Differences in Leaf Morphological Parameters of Pear (Pyrus communis L.) Based on Their Susceptibility to European Pear Rust Caused by Gymnosporangium sabinae (Dicks.) Oerst. Katrına¯ Karklin¯ , a , Gunars¯ Lacis¯ and Baiba Lace¯ * Institute of Horticulture, Graudu 1, LV-3701 Dobele, Latvia; [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (G.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: European pear rust is an important disease; however, the relationship between its causal pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae (Dicks.) Oerst. and host Pyrus communis L. is poorly understood. In this study, disease severity was measured, and leaf samples were collected over three years, and their leaf water content; leaf area; leaf mass per area; and epidermis, mesophyll, and vascular tissue width and stomatal density were measured and compared between susceptible and resistant genotypes for each year. Most genotypes either showed consistent disease symptoms or showed no symptoms during the study in terms of their susceptibility. A correlation between disease severity and mesophyll tissue thickness, and stomatal density and differences between several morphological parameters were found depending on the genotype’s susceptibility. The study showed that the following pear morphological traits were stable between the years: water content, leaf mass per area, spongy mesophyll thickness, phloem thickness, and stomatal density. When selecting for breeding, Citation: Karklin¯ , a, K.; Lacis,¯ G.; Lace,¯ B. Differences in Leaf we found that candidates for traits that discern susceptible genotypes from resistant were mesophyll Morphological Parameters of Pear layer width, stomatal density, epidermis width, and xylem tissue width. (Pyrus communis L.) Based on Their Susceptibility to European Pear Rust Keywords: European pear rust; Gymnosporangium sabinae; leaf anatomy Caused by Gymnosporangium sabinae (Dicks.) Oerst. -

Cedar Apple Rust

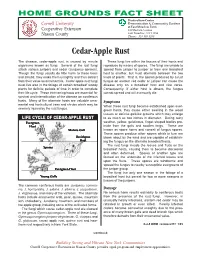

HOME GROUNDS FACT SHEET Horticulture Center Cornell University Demonstration & Community Gardens at East Meadow Farm Cooperative Extension 832 Merrick Avenue East Meadow, NY 11554 Nassau County Phone: 516-565-5265 Cedar-Apple Rust The disease, cedar-apple rust, is caused by minute These fungi live within the tissues of their hosts and organisms known as fungi. Several of the rust fungi reproduce by means of spores. The fungi are unable to attack various junipers and cedar (Juniperus species). spread from juniper to juniper or from one broadleaf Though the fungi usually do little harm to these trees host to another, but must alternate between the two and shrubs, they make them unsightly and thus detract kinds of plants. That is, the spores produced by a rust from their value as ornamentals. Cedar-apple rust fungi fungus on eastern red cedar or juniper can cause the must live also in the foliage of certain broadleaf woody disease only on a broadleaf host and vice versa. plants for definite periods of time in order to complete Consequently, if either host is absent, the fungus their life cycle. These intervening hosts are essential for cannot spread and will eventually die. survival and intensification of the disease on coniferous hosts. Many of the alternate hosts are valuable orna- Symptoms mental and horticultural trees and shrubs which may be When these rust fungi become established upon ever- severely injured by the rust fungus. green hosts, they cause either swelling in the wood tissues or definite gall-like growths which may enlarge LIFE CYCLE OF CEDAR-APPLE RUST to as much as two inches in diameter. -

Biotrophic Fungi Infection and Plant Defense Mechanism Solomon Abera Gebrie* Plant Biotechnology Research, P.O

atholog P y & nt a M Gebrie, J Plant Pathol Microbiol 2016, 7:9 l i P c f r o o b DOI: 10.4172/2157-7471.1000378 l i Journal of a o l n o r g u y o J ISSN: 2157-7471 Plant Pathology & Microbiology Review Article Open Access Biotrophic Fungi Infection and Plant Defense Mechanism Solomon Abera Gebrie* Plant Biotechnology Research, P.O. Box 31, Holeta, Ethiopia Abstract Biotrophic pathogens derive nutrients from living cells by maintaining host viability. This host Maintenance sustain through highly specialized structural and biochemical relations. For valuable virulence activity biotrophic fungi have: highly developed infection structures; limited secretory activity, carbohydrate rich and protein-containing interfacial layers; long-term suppression of host defense; haustoria that used for nutrient absorption and metabolism. Plant defenses biotrophic fungal pathogen by penetration resistance and program cell death (PCD). Plant strengthens cell wall and membrane to halt spore germination and prevent the formation of the haustorium by Penetration resistance. The second resistance mechanism applied inside the penetrated epidermal cell that terminates nutrient supply to fungi for further development by induction of invaded program cell death. Plant innate immune responses occur through two basic interconnected forms: pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) to activate defense signal molecules. However, Biotrophic fungi have several mechanisms to defend their effectors from plant receptor molecules. Once the fungal effector passes plant defense mechanism the plant will not resist. Subsequently the plant reduces production of defense signaling molecule like salicylic acid. This review overviews recent knowledge of biotrophic fungi infection and plant defense strategies. -

Crataegus (Hawthorn)

nysipm.cornell.edu 2019 Search for this title at the NYSIPM Publications collection: ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/41246 Disease and Insect Resistant Ornamental Plants Mary Thurn, Elizabeth Lamb, and Brian Eshenaur New York State Integrated Pest Management Program, Cornell University CRATAEGUS Hawthorn pixabay.com Crataegus is a large genus of shrubs and small trees in the rose family commonly known as hawthorn. This popular ornamental has showy pink or white flowers in spring and colorful berry-like fruit. Some species also have long thorns that provide protection for wildlife but may be a hazard in the landscape–thornless cultivars are available. Like other rosaceous plants, hawthorns are sus- ceptible to a number of diseases including fire blight, scab, leaf spot and several types of rust. Insect pests include lace bugs and leaf miners. DISEASES Cedar Rust diseases on hawthorn, which include hawthorn rust and quince rust, are caused by sev- eral fungi in the genus Gymnosporangium that spend part of their life cycle on Eastern red cedar (Juni- perus virginiana) and other susceptible junipers, and another part of their life cycle on plants in the rose family, especially Malus and Crataegus. Since two hosts are required for these fungi to complete their life cycle, one way to reduce disease problems is to avoid planting alternate hosts near each other. Hawthorn Rust, caused by Gymnosporangium globosum, is a significant concern for Crataegus spp. in the Northeast (7). Hawthorns are the main broadleaved host for this rust, and yellow-orange leaf spots are the most common symptom. (8). With severe infections, foliage may turn bright yellow and drop prematurely (15). -

Gymnosporangium Rust Management

Under the Scope: Gymnosporangium Rust Management We oen receive calls from homeowners requesng specific fungicide recommendaons and ming for managing the Cedar‐Apple Rust fungus or other closely related Gymnosporangium spp. that infect junipers and rosaceous hosts. You may find that there are many internet fact sheets on Cedar‐apple rust, (including our own) or other common Gymnosporangium rusts such as quince or hawthorn rust, and you may note that any given fact sheet may provide a specific fungicide recommendaon for treatment of one of these rusts and may even provide a general treatment me. Please keep in mind however that those recommendaons were likely made for the best me to manage that pest in that state! If your site is elsewhere, and you follow that recommendaon, you may get lile or no control and may waste an enre season treang at the wrong me. Galls of various species and stages of development on juniper. First provided by S. Jensen; remaining photos provided by D. Dailey O’Brien Managing Gymnosporangium rusts can be much more complicated than managing other disease issues for a couple of reasons. Each Gymnosporangium sp. has two unrelated hosts that the fungus requires to complete it’s life cycle. Spores produced on one host do not re‐infect that host, they infect the alternate host. So, when you want to treat your Juniper (or Eastern red cedar) to protect it, you need to treat when the alternate host (quince, pear, crabapple, etc.) is producing infecous spores, and vice versa. Timing of treatment also depends on the locaon of the trees! Treatment of a crabapple in Georgia on the same calendar date as treatment of a crabapple in New York is not likely to provide good results for both as sporulaon on the Juniper in those locaons is unlikely to occur on the same calendar date.