Introduction to Rust Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two New Chrysomyxa Rust Species on the Endemic Plant, Picea Asperata in Western China, and Expanded Description of C

Phytotaxa 292 (3): 218–230 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.292.3.2 Two new Chrysomyxa rust species on the endemic plant, Picea asperata in western China, and expanded description of C. succinea JING CAO1, CHENG-MING TIAN1, YING-MEI LIANG2 & CHONG-JUAN YOU1* 1The Key Laboratory for Silviculture and Conservation of Ministry of Education, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China 2Museum of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Two new rust species, Chrysomyxa diebuensis and C. zhuoniensis, on Picea asperata are recognized by morphological characters and DNA sequence data. A detailed description, illustrations, and discussion concerning morphologically similar and phylogenetically closely related species are provided for each species. From light and scanning electron microscopy observations C. diebuensis is characterized by the nailhead to peltate aeciospores, with separated stilt-like base. C. zhuoni- ensis differs from other known Chrysomyxa species in the annulate aeciospores with distinct longitudinal smooth cap at ends of spores, as well as with a broken, fissured edge. Analysis based on internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) partial gene sequences reveals that the two species cluster as a highly supported group in the phylogenetic trees. Correlations between the morphological and phylogenetic features are discussed. Illustrations and a detailed description are also provided for the aecia of C. succinea in China for the first time. Keywords: aeciospores, molecular phylogeny, spruce needle rust, taxonomy Introduction Picea asperata Mast.is native to western China, widely distributed in Qinghai, Gansu, Shaanxi and western Sichuan. -

Clarification of the Life-Cycle of Chrysomyxa Woroninii on Ledum

Mycol. Res. 104 (5): 581–586 (May 2000). Printed in the United Kingdom. 581 Clarification of the life-cycle of Chrysomyxa woroninii on Ledum and Picea Patricia E. CRANE1, 2, Yasuyuki HIRATSUKA2 and Randolph S. CURRAH1 " Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2E9, Canada # Northern Forestry Centre, Canadian Forest Service, 5320-122 Street, Edmonton, AB T6H 3S5, Canada. Accepted 5 August 1999. The rust fungus Chrysomyxa woroninii causes perennial witches’ brooms on several species of Ledum in northern and subalpine regions of Europe, North America and Asia. Spruce bud rust has been assumed to be the aecial state of C. woroninii because of the close proximity of infected Ledum plants and systemically infected buds on Picea. The lack of experimental evidence for this connection, however, and the presence of other species of Chrysomyxa on the same hosts has led to confusion about the life-cycle of C. woroninii. In this study, infections on both spruce and Ledum were studied in the field and in a greenhouse. The link between the two states was proven by inoculating spruce with basidiospores from Ledum groenlandicum. After infection of spruce in spring, probably through the needles, the fungus overwinters in the unopened buds until the next spring, when the infected shoots are distinguished by stunting and yellow or red discolouration. Microscopic examination of dormant Ledum shoots showed that C. woroninii overwinters in this host in the bracts and outer leaves of the vegetative buds, and in the pith and cortex of the stem. The telia of C. woroninii, on systemically infected Ledum leaves of the current season, are easily distinguished from the telia of other Chrysomyxa species on the same hosts. -

Molecular Evolution and Functional Divergence of Tubulin Superfamily In

OPEN Molecular evolution and functional SUBJECT AREAS: divergence of tubulin superfamily in the FUNGAL GENOMICS MOLECULAR EVOLUTION fungal tree of life FUNGAL BIOLOGY Zhongtao Zhao1*, Huiquan Liu1*, Yongping Luo1, Shanyue Zhou2, Lin An1, Chenfang Wang1, Qiaojun Jin1, Mingguo Zhou3 & Jin-Rong Xu1,2 Received 18 July 2014 1 NWAFU-PU Joint Research Center, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas, College of Plant Protection, 2 Accepted Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West 3 22 September 2014 Lafayette, IN 47907, USA, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Crop Diseases and Pests, Ministry of Education, Key Laboratory of Pesticide, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210095, China. Published 23 October 2014 Microtubules are essential for various cellular activities and b-tubulins are the target of benzimidazole fungicides. However, the evolution and molecular mechanisms driving functional diversification in fungal tubulins are not clear. In this study, we systematically identified tubulin genes from 59 representative fungi Correspondence and across the fungal kingdom. Phylogenetic analysis showed that a-/b-tubulin genes underwent multiple requests for materials independent duplications and losses in different fungal lineages and formed distinct paralogous/ should be addressed to orthologous clades. The last common ancestor of basidiomycetes and ascomycetes likely possessed two a a a b b b a J.-R.X. (jinrong@ paralogs of -tubulin ( 1/ 2) and -tubulin ( 1/ 2) genes but 2-tubulin genes were lost in basidiomycetes and b2-tubulin genes were lost in most ascomycetes. Molecular evolutionary analysis indicated that a1, a2, purdue.edu) and b2-tubulins have been under strong divergent selection and adaptive positive selection. -

Melampsora Medusae

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization PM 7/93 (1) Organisation Europe´enne et Me´diterrane´enne pour la Protection des Plantes Diagnostics Diagnostic Melampsora medusae Specific scope Specific approval and amendment This standard describes a diagnostic protocol for Melampsora Approved in 2009–09. medusae1 Populus trichocarpa, and their interspecific hybrids (Frey et al., Introduction 2005). In Europe, most of the cultivated poplars are P. · eur- Melampsora medusae Thu¨men is one of the causal agents of americana (P. deltoides · P. nigra)andP. · interamericana poplar rust. The main species involved in this disease in Europe (P. trichocarpa · P. deltoides) hybrids. In addition, Shain (1988) on cultivated poplars are Melampsora larici-populina and showed evidence for the existence of two formae speciales within Melampsora allii-populina. All three species cause abundant M. medusae and named them M. medusae f. sp. deltoidae and uredinia production on leaves, which can lead to premature M. medusae f. sp. tremuloidae according to their primary host, defoliation and growth reduction. After several years of severe Populus deltoides and Populus tremuloides, respectively. Neither infection leading to repeated defoliation, the disease may predis- the EU directive, nor the EPPO make the distinction between pose the trees to dieback or even death for the younger trees. these two formae speciales but only refer to M. medusae.Not- Melampsora rust is a very common disease of poplar trees, which withstanding, since M. medusae was only reported in Europe on can cause severe economic losses in commercial poplar cultiva- poplars from the sections Aigeiros and Tacamahaca,andin tion because of the emergence and spread of new pathotypes of respect with the host specialization, it can be stated that only M. -

PCBR 1956.Pdf (858.1Kb)

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Forest Service Region One BR REPORTS Annual - 1956 WHITE PINE BLISTER RUST CONTROL Calendar Year 1956 INF. IV. National Park Program I. Highlights of the 1956 Season The 1956 objectives of the National Park Service Region II white pine blister rust control program were accomplished. The program was planned and conducted as in previous years according to the cooperative arrangements between the Na- tional Park Service and the U. S. Forest Service. National Park Service personnel participating: Glacier Elmer Fladniark, chief ranger *A. D. Cannavina, s~pervisory park ranger Paul Webb, district ranger Yellowstone Otto Brown, chief ranger •~H. o. Edwards, assistant chief ranger Rocky Mountain: Harry During, chief ranger ->~Merle Stitt, staff ranger Grand Teton '-'"Ernest K. Field, chief r~ger Maynard Barrows, National Park Service consulting forester U. s .. forest Service· representatives: ~John C. Gynn, forester C. M. Chapman, forester The Na tionai Park Service Director approves new areas for -control. In January 1956, John c. Gynn met with National Park Service Region II Director Howard w. Baker, Regional Forester Frank ff. Childs, Fore:ster Maynard Barrows, and other members of their .s-taff at Omaha, "Nebraska, to review the results of the 1955 white pine and ribes survey on l7,270 acres of National Park lands. The group deter- mined ·the following areas should be incl\Jded in the pro;gram and the areas were later approved by the Director of the National Park Service. ~15- Glacier - expanded protection zones to present control areas only. Unit Acres Park Headquarters 300 East Glacier (Rising Sun Campground) 370 Twd Medicine 200 Total 870 Yellowstone New Unit Antelope Creek 1,390 Canyon 11,470 Fishing Bridge 2,090 Craig Pass (extension) 5,240 Total 20,190 Grand Teton New Unit Snake River (De adman 's Bar) 1,010 Grand Total 22,070 New areas surveyed at Roc~Mounta~~· At the request of Superintendent James V. -

Evolution of Isoprenyl Diphosphate Synthase-Like Terpene

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Evolution of isoprenyl diphosphate synthase‑like terpene synthases in fungi Guo Wei1, Franziska Eberl2, Xinlu Chen1, Chi Zhang1, Sybille B. Unsicker2, Tobias G. Köllner2, Jonathan Gershenzon2 & Feng Chen1* Terpene synthases (TPSs) and trans‑isoprenyl diphosphate synthases (IDSs) are among the core enzymes for creating the enormous diversity of terpenoids. Despite having no sequence homology, TPSs and IDSs share a conserved “α terpenoid synthase fold” and a trinuclear metal cluster for catalysis, implying a common ancestry with TPSs hypothesized to evolve from IDSs anciently. Here we report on the identifcation and functional characterization of novel IDS-like TPSs (ILTPSs) in fungi that evolved from IDS relatively recently, indicating recurrent evolution of TPSs from IDSs. Through large-scale bioinformatic analyses of fungal IDSs, putative ILTPSs that belong to the geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGDPS) family of IDSs were identifed in three species of Melampsora. Among the GGDPS family of the two Melampsora species experimentally characterized, one enzyme was verifed to be bona fde GGDPS and all others were demonstrated to function as TPSs. Melampsora ILTPSs displayed kinetic parameters similar to those of classic TPSs. Key residues underlying the determination of GGDPS versus ILTPS activity and functional divergence of ILTPSs were identifed. Phylogenetic analysis implies a recent origination of these ILTPSs from a GGDPS progenitor in fungi, after the split of Melampsora from other genera within the class of Pucciniomycetes. For the poplar leaf rust fungus Melampsora larici-populina, the transcripts of its ILTPS genes were detected in infected poplar leaves, suggesting possible involvement of these recently evolved ILTPS genes in the infection process. -

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

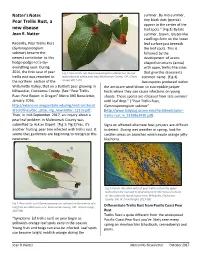

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol. VI - Introduction to Neotropical Entomology and Phytopathology - A. Bonet and G. Carrión INTRODUCTION TO NEOTROPICAL ENTOMOLOGY AND PHYTOPATHOLOGY A. Bonet Department of Entomology, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico G. Carrión Department of Biodiversity and Systematic, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Mexico Keywords: Biodiversity loss, biological control, evolution, hotspot regions, insect biodiversity, insect pests, multitrophic interactions, parasite-host relationship, pathogens, pollination, rust fungi Contents 1. Introduction 2. History 2.1. Phytopathology 2.1.1. Evolution of the Parasite-Host Relationship 2.1.2. The Evolution of Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Host Plants 2.1.3. Flor’s Gene-For-Gene Theory 2.1.4. Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Plant Parasitic Fungi and Hyperparasites 2.2. Entomology 2.2.1. Entomology in Asia and the Middle East 2.2.2. Entomology in Ancient Greece and Rome 2.2.3. New World Prehispanic Cultures 3. Insect evolution 4. Biodiversity 4.1. Biodiversity Loss and Insect Conservation 5. Ecosystem services and the use of biodiversity 5.1. Pollination in Tropical Ecosystems 5.2. Biological Control of Fungi and Insects 6. The future of Entomology and phytopathology 7. Entomology and phytopathology section’s content 8. ConclusionUNESCO – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchesSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Insects are among the most abundant and diverse organisms in terrestrial ecosystems, making up more than half of the earth’s biodiversity. To date, 1.5 million species of organisms have been recorded, although around 85% of potential species (some 10 million) have not yet been identified. In the case of the Neotropics, although insects are clearly a vital element, there are many families of organisms and regions that are yet to be well researched. -

The Pathogenicity and Seasonal Development of Gymnosporangium

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1931 The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa Donald E. Bliss Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Botany Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Bliss, Donald E., "The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa " (1931). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

SCIENCE Biodiversityand SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY

SCIENCE BIODIVERSITYand SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY A FINDINGS REPORT OF THE National Commission on Science for Sustainable Forestry A Program Conducted by the National Council for Science and the Environment Improving the scientific basis for environmental decisionmaking NCSE The mission of the National Commission on Science for Sustainable Forestry (NCSSF or Commission) is to improve the NCSSF operates under the scientific basis for developing, implementing, and evaluating sustainable auspices of the National forestry in the United States. Council for Science and The Commission is an independent, non-advocacy, multi-stakeholder the Environment (NCSE), body that plans and oversees the NCSSF program. It includes 16 leading a non-advocacy, not-for-profit scientists and forest management professionals from government, indus- organization dedicated to improving the scientific basis try, academia, and environmental organizations—all respected opinion for environmental decision leaders in diverse fields with broad perspectives. Members serve as making. individuals rather than as official representatives of their organizations. The Commission convenes at least twice a year to plan and oversee NCSE promotes interdiscipli- the program. Members’ names and affiliations are listed on page 2. nary research that connects The primary goal of the NCSSF program is to build a better scientific the life, physical, and social underpinning for assessing and improving sustainable forest management sciences and engineering. practices. The program strives to produce information and tools of the highest technical quality and greatest relevancy to improving forest Communication and outreach policy, management, and practice. are integral components of The initial five-year phase of the program focuses on the relationship these collaborative research between biodiversity and sustainable forest management. -

Spruce Tree Challenge! Take a Walk in the Woods with This Self-Guided Scavenger Hunt to Learn More About White and Black Spruce Trees

Spruce Tree Challenge! Take a walk in the woods with this self-guided scavenger hunt to learn more about white and black spruce trees. Developed for use in Denali National Park and Preserve, but adaptable to interior Alaska. 1. Meet a spruce tree—make a new friend! Spruce trees are evergreen trees with needles and cones. Take a walk and choose a spruce tree to “meet”; find one with cones on it. Then make and record observa- tions to find out what kind of spruce tree you just met. Please be kind to your new friend; touch it gently and leave all cones and branches on the tree. But, feel free to shake hands with or give your tree a hug when introducing yourself! Find the large cones near the top of your tree. Draw or describe their shape. What kind of spruce is your new friend? Circle one. Picea glauca (white spruce)- long cylindrical cones on branch ends and clustered near the top of the tree; has no hairs on the back of its twigs (hint: look between the needles near the end of a branch). White spruce prefers well drained, upland sites. Picea mariana (black spruce) - small oval cones often located along trunk and at the top of the tree; tiny red-brown hairs on the backs of twigs between needles (try a camera zoom or hand lens to see). Black spruce prefer low lying areas with more moisture like bogs or near wetlands. Clipart courtesy FCIT If you gave your friend a name, what would it be? __________________________ Want to share a picture of you and your new friend? Or meet other spruce friends? Post on social media with #sprucetreechallenge 2.