The Harsa-Carita of Bana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Yajur Veda to Vaisampayana, the Sama Veda to Jaimini and the Atharva Veda to Sumantu

Introduction to Vedic Knowledge second volume: The Four Original Vedas Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 1482598299 ISBN-13: 978-1482598292 published by Jagannatha Vallabha Research Center PAVAN House, Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Web presence: http://www.jagannathavallabha.com http://www.facebook.com/ParamaKarunaDevi http://jagannathavallabhavedicresearch.wordpress.com/ When, How and by Whom the Vedas Were Written In the previous chapters we have seen how Vedic knowledge has been perceived in the West and in India in the past centuries, and which misconceptions have developed because of the superimposition of various influences and motivations. We have also seen how Vedic knowledge transcends time and applies to reality itself, and how at each age it is again presented in the modalities and in the dimensions required to cater for the needs of the people of that age. Therefore when we speak of Vedic scriptures we refer not only to the original manuscripts that bear witness to the great antiquity of Hinduism in this age, but also to the previous versions of which we do not have copies, and also to the later texts compiled by self-realized souls that explain the original knowledge in harmony with the same eternal conclusions. For example in the case of the Puranas ("ancient stories") we see that the original version is presented and elaborated by a series of realized teachers. In the Bhagavata purana the two most prominent speakers are Sukadeva and Suta; Suta had received the knowledge of this Purana from Sukadeva when Sukadeva was speaking to King Parikshit and the Parama Karuna Devi other great sages assembled on the bank of the Ganges, and later he transmitted it to Saunaka and the other sages assembled at Naimisharanya. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Heartoflove.Pdf

Contents Intro............................................................................................................................................................. 18 Indian Mystics ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Brahmanand ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Palace in the sky .................................................................................................................................. 22 The Miracle ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Your Creation ...................................................................................................................................... 25 Prepare Yourself .................................................................................................................................. 27 Kabir ........................................................................................................................................................ 29 Thirsty Fish .......................................................................................................................................... 30 Oh, Companion, That Abode Is Unmatched ....................................................................................... 31 Are you looking -

Ganga As Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga's Rights Are Our Rights

Ganga as Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga’s Rights Are Our Rights Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswati Nearly 500 million people depend every day on the Ganga and Her tributaries for life itself. Like the most loving of mothers, She has served us, nourished us and enabled us to grow as a people, without hesitation, without discrimination, without vacation for millennia. Regardless of what we have done to Her, the Ganga continues in Her steady fl ow, providing the waters that offer nourishment, livelihoods, faith and hope: the waters that represents the very life-blood of our nation. If one may think of the planet Earth as a body, its trees would be its lungs, its rivers would be its veins, and the Ganga would be its very soul. For pilgrims, Her course is a lure: From Gaumukh, where she emerges like a beacon of hope from icy glaciers, to the Prayag of Allahabad, where Mother Ganga stretches out Her glorious hands to become one with the Yamuna and Saraswati Rivers, to Ganga Sagar, where She fi nally merges with the ocean in a tender embrace. As all oceans unite together, Ganga’s reach stretches far beyond national borders. All are Her children. For perhaps a billion people, Mother Ganga is a living goddess who can elevate the soul to blissful union with the Divine. She provides benediction for infants, hope for worshipful adults, and the promise of liberation for the dying and deceased. Every year, millions come to bathe in Ganga’s waters as a holy act of worship: closing their eyes in deep prayer as they reverently enter the waters equated with Divinity itself. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana abridged translation by Parama Karuna Devi new edition 2021 Copyright © 2016 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. ISBN: 9798530643811 published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center E-mail: [email protected] Blog: www.jagannathavallabhavedicresearch.wordpress.com Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Correspondence address: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center At Piteipur, P/O Alasana, PS Chandanpur, 752012 Dist. Puri Orissa, India Table of Contents Preface 5 The questions of the sages 7 The teachings of Sukadeva on yoga 18 Conversation between Maitreya and Vidura 27 The story of Varaha 34 The teachings of Kapila 39 The sacrifice of Daksha 56 The story of Dhruva 65 The story of king Prithu 71 The parable of Puranjana 82 The story of Rishabha 90 The story of Jada Bharata 97 The structure of the universe 106 The story of Ajamila 124 The descendants of Daksha 128 Indra and Vritrasura 134 Diti decides to kill Indra 143 The story of Prahlada 148 The varnashrama dharma system 155 The story of Gajendra 163 The nectar of immortality 168 The story of Vamana 179 The descendants of Sraddhadeva Manu 186 The story of Ambarisha 194 The descendants of Ikshvaku 199 The story of Rama 206 The dynastyof the Moon 213 Parama Karuna Devi The advent of Krishna 233 Krishna in the house of Nanda 245 The gopis fall in love with Krishna 263 Krishna dances with the gopis 276 Krishna kills more Asuras 281 Krishna goes to Mathura 286 Krishna builds the city of Dvaraka 299 Krishna marries Rukmini 305 The other wives of Krishna 311 The -

Linguistic Evidence for the Indo-European Pantheon

Krzysztof T. Witczak, Idaliana Kaczor Linguistic evidence for the Indo-European pantheon Collectanea Philologica 2, 265-278 1995 COLLECTANEA PHILOLOGICA II in honorem Annae Mariae Komornicka Łódź 1995 Krzysztof T. WITCZAK, Idaliana KACZOR Łódź, Poland LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE FOR THE INDO-EUROPEAN PANTHEON* I. GENERAL FEATURES OF THE INDO-EUROPEAN RELIGION (A) The Indo-European religion is polytheistic, i. e. it connects plurality of worships and cults peculiar to any group and any place. (B) It is a pagan or rustic religion, which reflects some variety of the common people. (C) It is plural and various. This religion is by nature broad-minded, being far from propagating its own faith. Any group preserves jealously its own deities, beliefs, rites and religious formules. In a sense this religion can be determined as esoteric and initiatory. It has mythes and symbols, but it knows no dogma. (D) It is a religion of work, but not of faith. The traditional rites and duties of their own social standing are engagements essential to confessors, but the affection does not figure prominently in their faith. (E) This religion is political for the sake of its frames, which are frames of different ethnic units. It is also a religion of commanders rather than that of priests. (F) It is highly tolerant and its confessors are devoid of any fanaticism, but both „superstition” and individual magic are despicable, thougt sometimes they are practised. (G) Indo-European deities are comprehended as personal beings, whose nature cannot be precisely determined. According to peoples and epochs their nature lies less or more near the human nature, as it can be recognized from theonyms. -

Contents Stotras, Krithis and Upamishads of Lord Narasimha

Stotras, Krithis and upamishads of Lord Narasimha (Originals in Sanskrit, Tamil, Malayalam and Hindi) Contents Stotras, Krithis and upamishads of Lord Narasimha .............................................................................................. 1 (Originals in Sanskrit, Tamil, Malayalam and Hindi) ............................................................................................... 1 Yoga Lakshmi Narasimha Suprabatham ...................................................................................................................... 2 Sri Pataladri Narasimha Peruman Sthuthi .............................................................................................................. 7 Prahladha vara pradhana sthuthi ............................................................................................................................... 8 Sri kamasikashtakam ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Shri Narasimha Pranama (Obeisances to Lord Nrisimha) ....................................................................................... 14 Narasimha Stuti by Shri Narayana Pandita Acarya .................................................................................................. 15 Lakshmi Narasimha Dandakam ................................................................................................................................. 19 Sri Yadagiri Lakshmi nrusimha praparthi ............................................................................................................... -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

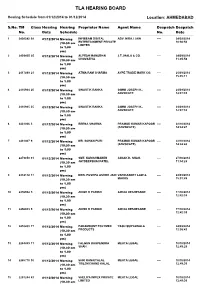

Tla Hearing Board

TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/12/2014 to 01/12/2014 Location: AHMEDABAD S.No. TM Class Hearing Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Despatch Despatch No. Date Schedule No. Date 1 2408242 99 01/12/2014 Morning INFIBEAM DIGITAL ADV. NIRAJ JAIN ---- 24/09/2014 (10.30 am ENTERTAINMENT PRIVATE 10:36:50 LIMITED to 1.00 pm) 2 2409405 25 01/12/2014 Morning ALPESH MANUBHAI J.T.JHALA & CO. ---- 24/09/2014 (10.30 am CHOVATIYA 11:05:56 to 1.00 pm) 3 2417899 21 01/12/2014 Morning ATMA RAM SHARMA AYPE TRADE MARK CO. ---- 25/09/2014 (10.30 am 15:05:17 to 1.00 pm) 4 2410944 20 01/12/2014 Morning SWASTIK RANKA GIMMI JOSEPH K., ---- 24/09/2014 (10.30 am ADVOCATE 12:07:33 to 1.00 pm) 5 2410945 35 01/12/2014 Morning SWASTIK RANKA GIMMI JOSEPH K., ---- 24/09/2014 (10.30 am ADVOCATE 12:07:34 to 1.00 pm) 6 2431006 3 01/12/2014 Morning BEENA SHARMA PRAMOD KUMAR KAPOOR ---- 22/10/2014 (10.30 am (ADVOCATE) 14:24:47 to 1.00 pm) 7 2431007 9 01/12/2014 Morning MR. SOHAN PURI PRAMOD KUMAR KAPOOR ---- 22/10/2014 (10.30 am (ADVOCATE) 14:24:48 to 1.00 pm) 8 2279850 31 01/12/2014 Morning SMT. KARISHMABEN JANAK R. SHAH. ---- 27/10/2014 (10.30 am JAYDEEPBHAI PATEL 11:54:25 to 1.00 pm) 9 2412112 17 01/12/2014 Morning MRS. PUSHPA ASHOK JAIN VARIKASERY LAW & ---- 24/09/2014 (10.30 am MARKS 15:01:49 to 1.00 pm) 10 2456932 5 01/12/2014 Morning ANISH R PARIKH GIRIJA DESHPANDE ---- 17/10/2014 (10.30 am 12:42:34 to 1.00 pm) 11 2456933 5 01/12/2014 Morning ANISH R PARIKH GIRIJA DESHPANDE ---- 17/10/2014 (10.30 am 12:42:35 to 1.00 pm) 12 2410433 17 01/12/2014 Morning PARAMOUNT -

Seattle Queer Film Festival

10-20 OCTOBER 2019 seattlequeerfilm.org Isn’t it time you planned your financial future? Photo Credit: Sabel Roizen We are excited to welcome you to the 24th annual Translations: Seattle Transgender Film Festival, Reel Seattle Queer Film Festival! The latest in queer cinema Queer Youth, Three Dollar Bill Outdoor Cinema; special from across the globe is being celebrated right here membership screenings; and, of course, the Seattle in our neighborhood, with 157 films from 28 countries Queer Film Festival. We are able to do this vital work in screening over 11 days. the community thanks to the generous support of our This year, the festival showcases many new voices and members, donors, and patrons. experiences, with films from around the world and right SQFF24 carries through it a message of resistance and here in Seattle, including the Northwest premiere of representation, and reflects the LGBTQ2+ community on Argentina’s Brief Story from the Green Planet, winner of the screen. We are thrilled to share these stories with you. Berlin Film Festival’s Teddy Award; and the world premiere We hope you’ll feel a sense of connection and strength in of No Dominion: The Ian Horvath Story by local filmmaker numbers throughout your viewing experience. Plot your course with someone who understands your needs. and Pacific Northwest Ballet principal soloist Margaret We’ll see you at the movies! Mullin. We also feature programs that give you a chance Financial Advisor Steve Gunn, who has earned the Accredited Domestic to reflect on the last 50 years since the Stonewall Riots, SM SM Partnership Advisor and Chartered Retirement Planning Counselor with films like State of Pride by renowned filmmakers Rob designations, can help you develop a strategy for making informed Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, a 30th anniversary screening decisions about your financial future.