Ears Up! Do We Really Need to Tape?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Also in This Issue Breeder Referral Proposal

The Official Newsletter of The American Whippet Club October 2014 Breeder Referral Proposal Specialty Best In Show: Fact & Fantasy Also in this issue AWC Official News Whippet News Annual Advertising Information 2015 National Information The American Whippet Club Guin Borstel, Newsletter Editor 4745 25th Street, San Francisco, CA . 94114 415 .826 .8853, awcwhippetnews@gmail .com Officers President . Harold “Red” Tatro, 817 .297 .2398, redglen@sbcglobal .net Cynthia Schmidt, Newsletter Graphic Design 610 .869 .3423, cynhounds@yahoo .com Vice President . Karen Lee, 610 .932 .4456, surreyhill@zoominternet .net One-year Subscriptions Treasurer . Gail Boyd, 919 .362 .4427, ableaimkennels@aol .com (includes Whippet Annual) Secretary . Guinevere Borstel, 415 .826 .8853, milescross@gmail .com Online-only newsletter . $40 4745 25th St ., San Francisco, CA 94114 Printed newsletter (plus online access) . $65 Foreign subscribers: online-only newsletter . $40 Board of Directors Printed newsletter (plus online access) . $80 Dr . Jill Hopfenbeck, 508 .278 .7102, jillhop1@charter .net Advertising Rates Dr . Ken Latimer, 706-296-5489, latimer49@gmail .com (available as space permits) Russell McFadden,505-570-1452, rlmcfadden@valornet .com $75 per page with one photo, each additional Crystal McNulty, 309 .579 .2946, hycks1@gmail .com photo $10 (non-camera-ready) Kathy Rasmussen, 913 .526 .5702, harmonywhippets@aol .com $60 per page submitted as camera-ready (pdfs preferred ) Class of 2015: Gail Boyd, Karen Lee, Crystal McNulty Text only, no photos: full page $50 Class of 2016: Guin Borstel, Dr . Jill Hopfenbeck, Harold “Red” Tatro half-page $35 Class of 2017: Dr . Ken Latimer, Russell McFadden, Kathy Rasmussen . Advertising Specifications Contact the Editor for file submission AWC Committee Chairs specifications . -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Advice on Finding a Well Reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy

ADVICE ON FINDING A WELL REARED STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER PUPPY We hope this booklet will offer you some helpful advice. Looking for that perfect new member to add to your family can be a daunting task - this covers everything you need to know to get you started on the right track. Advice on finding a well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy. It can be an exciting time looking for that new puppy to add to your family. You know you definitely want one that is a happy, healthy bundle of joy and so you should. You must remember there are many important things to consider as well and it is hoped this will help you to understand the correct way to go about finding a happy, healthy and well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier puppy. First things first, are you ready for a dog? Before buying a puppy or a dog, ask yourself: Most importantly, is a Stafford the right breed for me and/or my family? – Contact your local Breed Club Secretary to find out any local meeting places, shows, events or recommended breeders. Can I afford to have a dog, taking into account not only the initial cost of purchasing the dog, but also the on-going expenses such as food, veterinary fees and canine insurance? Can I make a lifelong commitment to a dog? - A Stafford’s average life span is 12 years. Is my home big enough to house a Stafford? – Or more importantly is my garden secure enough? Do I really want to exercise a dog every day? – Staffords can become very naughty and destructive if they get bored or feel they are not getting the time they deserve. -

Norfolk Terrier Ch Cracknor Cause Celebre Named Best in Show at 2003 Akc/Eukanuba National Championship

Contact: Kurt Iverson Daisy Okas Cori Cornelison The Iams Company American Kennel Club Fleishman-Hillard Dayton, OH New York, NY Kansas City, MO (937) 264-7436 212-696-8342 816-512-2351 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NORFOLK TERRIER CH CRACKNOR CAUSE CELEBRE NAMED BEST IN SHOW AT 2003 AKC/EUKANUBA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP — Show features top cash prize in the world; airs on Animal Planet & Discovery, — Jan. 31 at 8 p.m. — Long Beach, Calif. (Dec. 4, 2003) — And the winner is … Champion (Ch) Cracknor Cause Celebre, a five year old Norfolk Terrier, commonly known as “Coco.” Earning a $50,000 cash prize and the coveted title of AKC/Eukanuba National Champion, Coco was crowned the event’s top dog at the conclusion of the AKC/Eukanuba National Championship which was co-presented by The Iams Company last night (Dec. 3) in Long Beach, Calif. “This top dog embodies the finest breeding, temperament and quality. We are proud to have Coco as the winner of AKC/Eukanuba National Championship, representing the best of the purebred dog,” said Ron Menaker, AKC Chairman. “Rewarding these fine dogs is what the AKC/Eukanuba National Championship is all about. We congratulate her breeder, owners, and handler for this tremendous accomplishment.“ Coco is owned by Pamela Beale, Stephanie Ingram and Elizabeth Matell and is shown by AKC Registered Handler Beth K. Sweigart of Bowmansville, PA. Judge Frank T, Sabella of Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., awarded the National Champion title on Wednesday evening. “Coco, raised on Eukanuba, is truly the best of the best,” said Kelly Vanasse of The Iams Company. -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

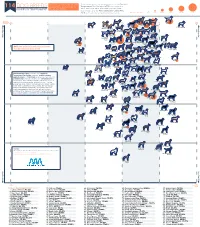

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

*ID: 304018 *Shelter Animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Black

*ID: 304018 *ID: 304034 *ID: 304073 *ID: 304074 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Chihuahua *American Bulldog *Black - White *blue - none *Black - Brown *Red - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304095 *ID: 304097 *ID: 304111 *ID: 304116 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *brindle - White *Black - White *White - none *Brown - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304117 *ID: 304150 *ID: 304170 *ID: 304173 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Yorkshire Terrier Yorkie *Pit Bull Terrier *blue - White *Black - White *Grey - none *Tan - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304192 *ID: 304195 *ID: 304196 *ID: 304205 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Chihuahua *Chihuahua *Pug *Beagle *APRICOT - none *Brown - White *Brown - none *tri - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304222 *ID: 304223 *ID: 304171 *ID: 299426 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Chihuahua *Chihuahua *Shepherd *Cockapoo - Cockapoo *Black - White *Brown - Black * none - none *Black - none *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *stray - 2nd pick up (not adoptable) *ID: 304172 *ID: 304187 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Labrador Retriever *Pit Bull Terrier *Black - none *brindle - none *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) Information Stray Animals Any animal that comes into the shelter without identification is held for a period 4 business days, or 7 business days if they have some identification (such as microchip, tatto0 or license/ID tags) per Michigan State Dog Law of 1919. -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

The Original Article in the AKC Gazette (November 2007)

InrecognitionofArmisticeDay,wesalutethedogswhoservedinWorldWarI. 1918. The 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th the first total war of the 20th century. It’s a war in which month. there was total mobilization of each of the major belliger- It was the moment millions of people had been praying ents,” says Imperial War Museum historian Terry for, for more than four horrifying years. Charman. “Everybody was brought in to conduct it, and All along the front, the pounding, shelling, and shooting dogs were part of that.” stopped. First came an odd silence, then, one man recalled Through January 6, the Imperial War Museum North is “a curious rippling sound, which observers far behind the featuring an exhibition, “The Animal’s War,” recognizing All front likened to the noise of a light wind. It was the sound the contributions of military beasts—from message-carrying of men cheering from the Vosges to the sea.” pigeons to elephants who hauled heavy equipment. The Great War was over. Dogs, Charman says, were used extensively during There was also a lot of tail wagging. When the guns quit World War I. They were on the front lines, dashing across barking, at least 10,000 dogs were at the front. They were No Man’s Land, carrying messages or searching for the soldiers, too. wounded. They hauled machine guns, light artillery, and “They ranged from Alaskan malamute to Saint Bernard carts loaded with ammunition, food, medicine, and some- and from Scotch collie to fox terrier,” a newspaper times wounded soldiers. Small dogs trotted among the reported. -

The Westfield Leader

THE WESTFIELD LEADER THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN ONION COUNTY THIS T.THATtTKT/1 A wr* MAflm HFTTMUT tr nmnrrr A mnn nrraTtivr tr tmttrn n A nno •»• *«•*•*•« <«*>**•••• ^^ Entered as Hoeouil Clans Matter rout Office. Weat field, N. J. WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 1959 PublUhad Bverjr Tl.'ir«dar 32 Pages—10 Cent* Day of Prayer Dr. Christian 3ters Elect 4 Observance Set Will Speak At .71 Tax Rate Indicated XI Candidates For Tomorrow Lenten Service In Proposed Town Budget Dr. Jule Ayers Famous Preachers d Budget Borough Voters Will Give Talk Series to Open Approve Budget In Baptist Church This Evening Office Zone Increase of 60 Points Over MOUNTAINSIDE — The pro Approved (Picture on page 2) Dr. Frederick Christian, pastor posed school budget for 1959-60 Principal speaker for tomorrow'_ of the Presbyterian Church, will Last Year; Hea ring March 9 was approved almost 10 to 1 by 73rd world-wide observance of the preach nt the opening service in PlannedFor .[Margin borough voters Tuesday night. A World Day of Prayer in West- the 195!) Famous Preachers Lent- A proposed budget totaling $2,325,813.03, of which $1,185,988.03 total of 175 residents voted. field will be Dr. Juli! Ayers, min- en scries to be held tonight at 8 la to be raised by taxation, was introduced by the Town Council Mon- school"board election that Current expenses of $510,875 ister of the First Presbyterian o'clock in St. Paul's Episcopal Town Edge day night. The total 1950 tnx rate Is estimated at $8.71 per $100 "oters go to the polls were approved 159-14; repairs Church, Wilkes-Barrc, Pa. -

Norfolk Terrier

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1 er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ 16.02.2011/EN FCI-Standard N° 272 NORFOLK TERRIER ©J.Campin, illustr. KC Picture Library This illustration does not necessarily show the ideal example of the breed. 2 ORIGIN : Great Britain. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD : 13.10.2010. UTILIZATION : Terrier. FCI-CLASSIFICATION : Group 3 Terriers. Section 2 Small-sized Terriers. Without working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY : The Norfolk and Norwich Terrier take their names, obviously, from the county and the city, though turning the clock back to the early and mid-1800s there was no such distinction, this being just a general farm dog. Glen of Imaals, red Cairn Terriers and Dandie Dinmonts are among the breeds behind these East Anglian terriers and from the resultant red progeny emerged the present Norwich and Norfolk Terrier. A typical short-legged terrier with a sound, compact body which has been used not only on fox and badger, but on rats as well. He has a delightful disposition, is totally fearless but is not one to start a fight. As a worker he does not give up in the face of a fierce adversary underground, and his standard’s reference to the acceptability of ‘honourable scars from fair wear and tear’ is a good indication of the type of. The Norwich Terrier was accepted on the Kennel Club Breed Register in 1932, and were known as the drop-eared Norwich Terrier (now known as the Norfolk Terrier) and prick-eared Norwich Terrier. -

Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY

Military Working Dog History Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY NOLAN A. WATSON, MLA* INTRODUCTION COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR WORLD WAR I WORLD WAR II KOREAN WAR AND THE EARLY COLD WAR VIETNAM WAR THE MILITARY WORKING DOG CONCLUSION *Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Regimental Historian; AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Medical Command, 2748 Worth Road, Suite 28, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Branch Historian, Military Police Corps, US Army Military Police School, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri 83 Military Veterinary Services INTRODUCTION History books recount stories of dogs accompany- which grew and changed with subsequent US wars. ing ancient armies, serving as sources of companion- Currently, US forces utilize military working dogs ship and performing valuable sentry duties. Dogs also (MWDs) in a variety of professions such as security, fought in battle alongside their owners. Over time, law enforcement, combat tracking, and detection (ie, however, the role of canines as war dogs diminished, for explosives and narcotics). Considered an essential especially after firearms became part of commanders’ team member, an MWD was even included in the arsenals. By the 1800s and up until the early 1900s, the successful raid against Osama Bin Laden in 2011.1 (See horse rose to prominence as the most important mili- also Chapter 3, Military Working Dog Procurement, tary animal; at this time, barring some guard duties, Veterinary Care, and Behavioral Services for more dogs were relegated mostly to the role of mascots. It information about the historic transformation of the was not until World War II that the US Army adopted MWD program and the military services available broader roles for its canine service members—uses for canines.) COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR Early American Army dogs were privately owned tary continued throughout the next century and into at first; there was neither a procurement system to the American Civil War.