A History of the Binomial Classification of the Polynesian Native Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ageing in Dogs (Canis Familiaris) and Its Relationship to Their Environment

AGEING IN DOGS (CANIS FAMILIARIS) AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THEIR ENVIRONMENT LUÍSA MASCARENHAS LADEIA DUTRA PhD Thesis 2019 Ageing in dogs (Canis Familiaris) and its rela- tionship to their environment Luísa Mascarenhas Ladeia Dutra This thesis is presented to the School of Environmental & Life Science, University of Salford, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. Supervised by Professor Robert J. Young Co-supervised by Professor Jean Phillippe Boubli March 2019 Table of contents Chapter 1 General Introduction ......................................................................... 19 1.1 Animal Welfare Assessment ................................................................... 19 1.2 Evaluation of stress levels as a measure of animal welfare .................... 21 1.3 Telomeres as biological clocks ................................................................ 25 1.4 Apparent age as a measure of life experience ........................................ 29 1.5 Canids as a model group ........................................................................ 31 1.6 Thesis structure ....................................................................................... 32 Chapter 2 Validating the use of oral swabs for telomere length assessment in dogs 34 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................. 34 2.2 Objective ................................................................................................. 37 2.3 Justification ............................................................................................ -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

Exceptional Longevity and Potential Determinants Of

Adams et al. Acta Vet Scand (2016) 58:29 DOI 10.1186/s13028-016-0206-7 Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica RESEARCH Open Access Exceptional longevity and potential determinants of successful ageing in a cohort of 39 Labrador retrievers: results of a prospective longitudinal study Vicki Jean Adams1*, Penny Watson2, Stuart Carmichael3, Stephen Gerry4, Johanna Penell5 and David Mark Morgan6 Abstract Background: The aim of this study was to describe the longevity and causes of mortality in 39 (12 males, 27 females) pedigree adult neutered Labrador retrievers with a median age of 6.5 years at the start of the study and kept under similar housing and management conditions. Body condition score was maintained between two and four on a 5-point scale by varying food allowances quarterly. The impact of change in body weight (BW) and body composition on longevity was analysed using linear mixed models with random slopes and intercepts. Results: On 31 July 2014, 10 years after study start, dogs were classified into three lifespan groups: 13 (33 %) Expected ( 9 to 12.9 years), 15 (39 %) Long ( 13 to 15.5 years) and 11 (28 %) Exceptional ( 15.6 years) with five still alive.≥ Gender≤ and age at neutering were≥ not associated≤ with longevity (P 0.06). BW increased≥ similarly for all lifespan groups up to age 9, thereafter, from 9 to 13 years, Exceptional dogs gained≥ and Long-lifespan dogs lost weight (P 0.007). Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometer scans revealed that absolute fat mass increase was slower to age 13 for =Long compared with Expected lifespan dogs (P 0.003) whilst all groups lost a similar amount of absolute lean mass (P > 0.05). -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Advice on Finding a Well Reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy

ADVICE ON FINDING A WELL REARED STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER PUPPY We hope this booklet will offer you some helpful advice. Looking for that perfect new member to add to your family can be a daunting task - this covers everything you need to know to get you started on the right track. Advice on finding a well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy. It can be an exciting time looking for that new puppy to add to your family. You know you definitely want one that is a happy, healthy bundle of joy and so you should. You must remember there are many important things to consider as well and it is hoped this will help you to understand the correct way to go about finding a happy, healthy and well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier puppy. First things first, are you ready for a dog? Before buying a puppy or a dog, ask yourself: Most importantly, is a Stafford the right breed for me and/or my family? – Contact your local Breed Club Secretary to find out any local meeting places, shows, events or recommended breeders. Can I afford to have a dog, taking into account not only the initial cost of purchasing the dog, but also the on-going expenses such as food, veterinary fees and canine insurance? Can I make a lifelong commitment to a dog? - A Stafford’s average life span is 12 years. Is my home big enough to house a Stafford? – Or more importantly is my garden secure enough? Do I really want to exercise a dog every day? – Staffords can become very naughty and destructive if they get bored or feel they are not getting the time they deserve. -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

Ranked by Temperament

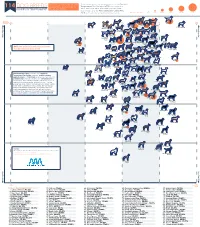

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

*ID: 304018 *Shelter Animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Black

*ID: 304018 *ID: 304034 *ID: 304073 *ID: 304074 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Chihuahua *American Bulldog *Black - White *blue - none *Black - Brown *Red - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304095 *ID: 304097 *ID: 304111 *ID: 304116 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *brindle - White *Black - White *White - none *Brown - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304117 *ID: 304150 *ID: 304170 *ID: 304173 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Pit Bull Terrier *Pit Bull Terrier *Yorkshire Terrier Yorkie *Pit Bull Terrier *blue - White *Black - White *Grey - none *Tan - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304192 *ID: 304195 *ID: 304196 *ID: 304205 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Chihuahua *Chihuahua *Pug *Beagle *APRICOT - none *Brown - White *Brown - none *tri - White *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *ID: 304222 *ID: 304223 *ID: 304171 *ID: 299426 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Chihuahua *Chihuahua *Shepherd *Cockapoo - Cockapoo *Black - White *Brown - Black * none - none *Black - none *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) *stray - 2nd pick up (not adoptable) *ID: 304172 *ID: 304187 *Shelter animal *Shelter animal *Labrador Retriever *Pit Bull Terrier *Black - none *brindle - none *Stray (not adoptable) *Stray (not adoptable) Information Stray Animals Any animal that comes into the shelter without identification is held for a period 4 business days, or 7 business days if they have some identification (such as microchip, tatto0 or license/ID tags) per Michigan State Dog Law of 1919. -

Localization of Metallothioneins-I & -II and -III in the Brain of Aged

Localization of Metallothioneins-I & -II and -III in the Brain of Aged Dog Seiji KOJIMA, Akinori SHIMADA*, Takehito MORITA, Yoshiaki YAMANO1) and Takashi UMEMURA2) Departments of Veterinary Pathology and 1)Metabolic Biochemistry, Tottori University, Minami 4-101, Tottori-shi, Tottori 680-0945, and 2)Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido 060–0818, Japan (Received 2 November 1998/Accepted 7 December 1998) ABSTRACT. Localization of metallothionein (MT) -I & -II and MT-III and its significance in the brain aging in dogs were examined using immunohistological and molecular pathological techniques. MT-I & -II immunohistochemistry showed positive staining in the hypertrophic astrocytes throughout the aged dog brains; these MT-I & -II immunoreactive astrocytes were predominant in the cerebral cortex and around the blood vessels in the brain. These findings dominated in the brain regions with severe age-related morphological changes. In situ hybridization using MT-I mRNA riboprobes also demonstrated signals for MT-I mRNA in these hypertrophic astrocytes. Immunohistochemistry using a guinea pig antiserum against a synthetic polypeptide of canine MT-III demonstrated positive MT-III immunoreactivity predominantly in neurons in the Zn-rich regions such as hippocampus and parahippocampus. The findings were supported by in situ hybridization using MT-III mRNA riboprobes. Both MT-III immunoreactivity and signals for MT-III mRNA were demonstrated in neurons in the brain regardless of the intensity of the age-related changes. These results suggest, first, MT-I & -II may be induced in relation to the progress of the age-related morphological changes in the brain, playing an important role in the protection of the brain tissue from the toxic insults responsible for the brain aging, and second, MT-III may play a role in maintenance of Zn-related essential functions of the brain.—KEY WORDS: aging, brain, canine, in situ hybridization, metallothionein. -

Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: the Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy Vankavage

Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Advoca'ng*for* Pit*Bull*Terriers* *A6orney*Fred*Kray,*Pit$Bulle)n$Legal$ News,*presen'ng*the*Wallace*Award* to*Lori*Weise,*Downtown*Dog*Rescue* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 1 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Ledy%VanKavage,%Esq.% Sr.*Legisla've*A6orney* Past*Chair*of*American*Bar* Associa'on’s*TIPS’*Animal* Law*Commi6ee* [email protected]* Karma*at*Fight*Bust*BunKer*before*adop'on** * (photo*by*Lynn*Terry)* * No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 2 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage Join%Voices%for%No%More%Homeless%Pets% * % * capwiz.com/besJriends* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 3 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage *“Pit*bull*terriers*have* been*trained*to*be* successful*therapy*dogs* with*developmentally* disabled*children.”* Jonny*Jus'ce,*a*former*VicK*dog,*is*now*a* model*for*a*Gund*stuffed*toy.* No More Homeless Pets National Conference October 10-13, 2013 4 Advocating for Pit Bull Terriers: The Surprising Truths Revealed by the Latest Research – Ledy VanKavage “Pit*bull*terriers*are*extremely* intelligent,*making*it*possible*for* them*to*serve*in*law*enforcement* and*drug*interdic'on,*as*therapy* dogs,*as*search*and*rescue*dogs,* -

Behavior Tips: Choosing the Right Dog for the Right Family Provided By

Behavior Tips: Choosing the right dog for the right family Provided by: There are many factors to consider when choosing the right dog for your behaviorally. This is when housemates may start fighting with each family: your expectations for the dog, possible effects on your lifestyle, other over toys, attention…anything. Interestingly, research shows that and the time the dog will require. Breed, sex, and individual or familial two female dogs are most likely to fight, and a male and female pair is characteristics also require thought. Breeds were developed for jobs, least likely to do so1. and that job – herding, carting , or being a lap dog - affects how dogs The special case of adult dogs - Nothing in life is guaranteed, but adult behave. Dogs from working dog lines are behaviorally different than dogs can be known entities, compared to puppies. If that dog has lived dogs from pet lines. You need to know whether these concerns apply to with someone for at least 1 month that person may be able to tell you your dog. about the individual dog’s personality, likes, dislikes, et cetera. Dogs from breed rescues are generally assessed to see which home style is Exercise requirements: Do you want a running partner? If so a young, best for them. More shelters are trying to do these types of evaluations. healthy, large breed dog such as a Labrador or golden retriever may be a Dogs may still behave differently in a new home and everyone should good match. If a couch potato is more your speed consider a small or toy know about the “honeymoon period”. -

Behavioural and Cognitive Changes in Aged Pet Dogs: No Effects of an Enriched Diet and Lifelong Training

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Behavioural and cognitive changes in aged pet dogs: No effects of an enriched diet and lifelong training 1,2 3,4 1,2 5 Durga ChapagainID *, Lisa J. Wallis , Friederike Range , Nadja Affenzeller , Jessica Serra6, Zso fia ViraÂnyi1 1 Clever Dog Lab, Comparative Cognition, Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Medical University of Vienna, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2 Domestication Lab, Konrad Lorenz Institute of Ethology, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 3 Department of a1111111111 Livestock and One Health, Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool, a1111111111 Liverpool, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Ethology, EoÈtvoÈs LoraÂnd University, Budapest, Hungary, a1111111111 5 Department/Clinic for Companion Animals and Horses, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Vienna, a1111111111 Austria, 6 Royal Canin Research Centre, Aimargues, France a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Dogs demonstrate behavioural changes and cognitive decline during aging. Compared to Citation: Chapagain D, Wallis LJ, Range F, Affenzeller N, Serra J, ViraÂnyi Z (2020) Behavioural laboratory dogs, little is known about aging in pet dogs exposed to different environments and cognitive changes in aged pet dogs: No effects and nutrition. In this study, we examined the effects of age, an enriched diet and lifelong of an enriched diet and lifelong training. PLoS ONE training on different behavioural and cognitive measures in 119 pet dogs (>6yrs). Dogs were 15(9): e0238517. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0238517 maintained on either an enriched diet or a control diet for one year. Lifelong training was cal- culated using a questionnaire where owners filled in their dog's training experiences to date.