Base Articolo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloading the Application Form at the Following Address

Hanno Collaborato A queSto NumeRo: IL NUOVO SAGGIATORE f. K. A. Allotey, L. Belloni, BOLLETTINO DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI FISICA G. Benedek, A. Bettini, t. m. Brown, Nuova Serie Anno 26 • N. 5 settembre-ottobre 2010 • N. 6 novembre-dicembre 2010 f. Brunetti, G. Caglioti, R. Camuffo, A. Cammelli, e. Chiavassa, DIRETTORE RESPONSABILE ViCeDiRettoRi ComitAto scieNtifiCo L. Cifarelli, e. De Sanctis, A. Di Carlo, Luisa Cifarelli Sergio focardi G. Benedek, A. Bettini, i. Di Giovanni, R. fazio, f. ferrari, Giuseppe Grosso S. Centro, e. De Sanctis, S. focardi, R. Gatto, A. Gemma, e. iarocci, i. ortalli, L. Grodzins, G. Grosso, f. Guerra, f. Palmonari, R. Petronzio, f. iachello, W. Kininmonth, e. Longo, P. Picchi, B. Preziosi S. mancini, P. mazzoldi, A. oleandri, G. onida, V. Paticchio, f. Pedrielli, A. Reale, G. C. Righini, N. Robotti, W. Shea, i. talmi, A. tomadin, m. Zannoni, A. Zichichi Sommario 3 EDITORIALE / EDITORIAL 84 50 anni di laser. Tavola rotonda al XCVI Congresso Nazionale della SIF SCieNZA iN PRimO PIANO G. C. Righini 5 Quantum simulators and 86 Assemblea di ratifica delle elezioni quantum design delle cariche sociali della SIF per il R. fazio, A. tomadin triennio 2011-2013 10 La rivoluzione della plastica nel 87 African Physical Society settore fotovoltaico f. K. A. Allotey A. Di Carlo, A. Reale, t. m. Brown, 90 Nicola Cabibbo and his role in f. Brunetti elementary-particle theory Percorsi R. Gatto 23 The tabletop measurement of the News helicity of the neutrino 92 The Italian graduate profile survey L. Grodzins A. Cammelli 30 Giulio Racah (1909-1965): 96 Premio Fermi 2010 modern spectroscopy A. -

Project Note Weston Solutions, Inc

PROJECT NOTE WESTON SOLUTIONS, INC. To: Canadian Radium & Uranium Corp. Site File Date: June 5, 2014 W.O. No.: 20405.012.013.2222.00 From: Denise Breen, Weston Solutions, Inc. Subject: Determination of Significant Lead Concentrations in Sediment Samples References 1. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Technical Guidance for Screening Contaminated Sediments. March 1998. [45 pages] 2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Emergency Response. Establishing an Observed Release – Quick Reference Fact Sheet. Federal Register, Volume 55, No. 241. September 1995. [7 pages] 3. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry Division Commission on Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances. Atomic Weights of Elements: Review 2000. 2003. [120 pages] WESTON personnel collected six sediment samples (including one environmental duplicate sample) from five locations along the surface water pathway of the Canadian Radium & Uranium Corp. (CRU) site in May 2014. The sediment samples were analyzed for Target Analyte List (TAL) Metals and Stable Lead Isotopes. 1. TAL Lead Interpretation: In order to quantify the significance for Lead, Thallium and Mercury the following was performed: 1. WESTON personnel tabulated all available TAL Metal data from the May 2014 Sediment Sampling event. 2. For each analyte of concern (Lead, Thallium, and Mercury), the highest background concentration was selected and then multiplied by three. This is the criteria to find the significance of site attributable release as per Hazard Ranking System guidelines. 3. One analytical lead result (2222-SD04) of 520 mg/kg (J) was qualified with an unknown bias. In accordance with US EPA document “Using Data to Document an Observed Release and Observed Contamination”, 2222-SD03 lead concentration was adjusted by dividing by the factor value for lead of 1.44 to equal 361 mg/kg. -

Guide to the Enrico Fermi Collection 1918-1974

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Enrico Fermi Collection 1918-1974 © 2009 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 4 Information on Use 4 Access 4 Citation 4 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 7 Related Resources 8 Subject Headings 8 INVENTORY 8 Series I: Personal 8 Subseries 1: Biographical 8 Subseries 2: Personal Papers 11 Subseries 3: Honors 11 Subseries 4: Memorials 19 Series II: Correspondence 22 Subseries 1: Personal 23 Sub-subseries 1: Social 23 Sub-subseries 2: Business and Financial 24 Subseries 2: Professional 25 Sub-subseries 1: Professional Correspondence A-Z 25 Sub-subseries 2: Conferences, Paid Lectures, and Final Trip to Europe 39 Sub-subseries 3: Publications 41 Series III: Academic Papers 43 Subseries 1: Business and Financial 44 Subseries 2: Department and Colleagues 44 Subseries 3: Examinations and Courses 46 Subseries 4: Recommendations 47 Series IV: Professional Organizations 49 Series V: Federal Government 52 Series VI: Research 60 Subseries 1: Research Institutes, Councils, and Foundations 61 Subseries 2: Patents 64 Subseries 3: Artificial Memory 67 Subseries 4: Miscellaneous 82 Series VII: Notebooks and Course Notes 89 Subseries 1: Experimental and Theoretical Physics 90 Subseries 2: Courses 94 Subseries 3: Personal Notes on Physics 96 Subseries 4: Miscellaneous 98 Series VIII: Writings 99 Subseries 1: Published Articles, Lectures, and Addresses 100 Subseries 3: Books 114 Series IX: Audio-Visual Materials 118 Subseries 1: Visual Materials 119 Subseries 2: Audio 121 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.FERMI Title Fermi, Enrico. Collection Date 1918-1974 Size 35 linear feet (65 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. -

The Prodigious Life and Untimely Death of “Harry” Moseley

The prodigious life and untimely death of “Harry” Moseley Bretislav Friedrich Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society, Faradayweg 4-6, D-14195 Berlin “My Harry was killed in the Dardanelles” is the entry from 10 August 1915 in the diary of the mother of Henry (“Harry”) Gwin Jeffreys Moseley. He was shot on that day in the head during the failed Anglo-French invasion of the Ottoman Empire from the sea. The previous year, when he volunteered to join Lord Kitchener’s New Army, he was nominated for two Nobel Prizes, one for chemistry and one for physics, for his work on X-ray spectroscopy and atomic structure. Moseley’s tragic death at age 27 was widely reported not just in the Allied countries, but also in Germany. Its futility fired up Ernest Rutherford, Moseley’s mentor, to write an indignant letter to Nature: “It is a national tragedy that our military organization at the start of the war was so inelastic as to be unable, with a few exceptions, to utilise the scientific services of our men, except as combatants in the firing line. Our regret for the untimely death of Moseley is all the more poignant.” Three years before, as Rutherford’s affiliate at the University of Manchester, Moseley recognized that “a platinum target [upon electron impact] gives out a sharp line [X-ray] spectrum … which [a] crystal separates out [into monochromatic lines] as if it were a diffraction grating … There is here a whole new branch of spectroscopy which is sure to tell one much about the nature of an atom.” This letter of Moseley, addressed, as so many of his other letters, to his mother, marks the beginning of X-ray spectroscopy. -

April 1997 Vol

Events and Happenings in the SLAC Community ^Interaction Point April 1997 Vol. 8 No. 4 Panofsky Awarded Matteucci Medal SLAC's DIRECTOR EMERI- trained as a chemist and physiologist but also had TUS, Professor Wolfgang K. a strong interest in physics. Mattuecci's work con- H. Panofsky was awarded centrated on electrical effects on chemical systems Italy's Matteucci Medal for and on biological systems including animals (he outstanding merit in Phys- did a special study of the electric eel). He had an ics. The award ceremony illustrious career, and during his later years be- took place in Italy on March came heavily involved in administrative and po- 22, 1997, during the school litical responsibilities. In 1866, he became the presi- year's opening ceremony of dent of the Quaranta Academy. Italy's National Academy of The Matteucci medal was endowed one year · ___ __ _/1 - L 'VT \ and the administration of Science (known as the AL). before his death in 1867, The Accademia Nazionale Della Scienze Detta the medal was continued by his wife, Robinia Dei XL, usually known as the Accademia Quaranta, Young-Matteucci. In a proclamation of Victorio was founded in 1785 in Verona, Italy in a national- Emmanuele II on July 10, 1870, the Italian Society istic Italian spirit to utilize science in bringing for the Sciences decreed that a "fine Matteucci together the disconnected and often hostile Italian medal of gold" would be conferred each year to provinces. It consisted of 40 members from all members of the Italian and foreign physics com- parts of the country. -

Einstein, L'italia E L'accademia Dei XL. Considerazioni E Documenti Inediti

Rendiconti Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze detta dei XL Memorie e Rendiconti di Chimica, Fisica, Matematica e Scienze Naturali 138° (2020), Vol. I, fasc. 3, pp. 263-278 ISSN 0392-4130 • ISBN 978-88-98075-41-6 Einstein, l’Italia e l’Accademia dei XL. Considerazioni e documenti inediti FRANCO CALASCIBETTA* – MARCO CIARDI** * Già Ricercatore del Dipartimento di Chimica all’Università La Sapienza di Roma E.mail: [email protected] ** Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia, Università di Firenze - E.mail: [email protected] Abstract – Einstein, Italy, and the Academy of the XL. Some remarks and unpubli- shed documents. The National Academy of Sciences called Academy of the XL houses some unpublished documents related to Albert Einstein. Einstein won the “Matteucci Medal” in 1921 and was appointed foreign member of the Academy in 1925. The docu- ments are presented and briefly analyzed in their context. Keywords: Einstein, Academy of the XL, Matteucci Medal Riassunto – L’Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze, detta dei XL, conserva alcuni documenti relativi ad Albert Einstein. Einstein vinse la “Medaglia Matteucci” nel 1921 e venne nominato Socio straniero nel 1925. I documenti sono qui presentati e analizzati brevemente nel loro contesto. Parole chiave: Einstein, Accademia dei XL, Medaglia Matteucci 1921: Einstein in Italia Il 6 novembre 1919 la Royal Society e la Royal Astronomical Society di Lon- dra, le istituzioni che avevano organizzato le spedizioni scientifiche, coordinate da Frank Watson Dyson (1868-1939) e Arthur Eddington (1882-1944), incari- cate di verificare la deflessione dei raggi di luce in un campo gravitazionale (grazie all’eclissi totale di Sole del 29 maggio 1919), annunciarono, congiunta- mente, che i raggi erano stati effettivamente deviati così come previsto dalla teoria della relatività generale di Albert Einstein. -

Technetium 1 Technetium

Technetium 1 Technetium Technetium Appearance shiny gray metal General properties Name, symbol, number technetium, Tc, 43 Pronunciation /tɛkˈniːʃiəm/ tek-NEE-shee-əm Element category transition metal Group, period, block 7, 5, d Standard atomic weight [98] g·mol−1 Electron configuration [Kr] 4d5 5s2 Electrons per shell 2, 8, 18, 13, 2 (Image) Physical properties Phase solid Density (near r.t.) 11 g·cm−3 Melting point 2430 K,2157 °C,3915 °F Boiling point 4538 K,4265 °C,7709 °F Heat of fusion 33.29 kJ·mol−1 Heat of vaporization 585.2 kJ·mol−1 Specific heat capacity (25 °C) 24.27 J·mol−1·K−1 Vapor pressure (extrapolated) P/Pa 1 10 100 1 k 10 k 100 k at T/K 2727 2998 3324 3726 4234 4894 Atomic properties [1] [2] Oxidation states 7, 6, 5, 4, 3 , 2, 1 , -1, -3 (strongly acidic oxide) Electronegativity 1.9 (Pauling scale) Ionization energies 1st: 702 kJ·mol−1 2nd: 1470 kJ·mol−1 3rd: 2850 kJ·mol−1 Atomic radius 136 pm Covalent radius 147±7 pm Miscellanea Technetium 2 Crystal structure hexagonal close packed Magnetic ordering Paramagnetic Thermal conductivity (300 K) 50.6 W·m−1·K−1 Speed of sound (thin rod) (20 °C) 16,200 m/s CAS registry number 7440-26-8 Most stable isotopes iso NA half-life DM DE (MeV) DP 95mTc syn 61 d ε - 95Mo γ 0.204, - 0.582, 0.835 IT 0.0389, e 95Tc 96Tc syn 4.3 d ε - 96Mo γ 0.778, - 0.849, 0.812 97 6 97 Tc syn 2.6×10 y ε - Mo 97mTc syn 91 d IT 0.965, e 97Tc 98Tc syn 4.2×106 y β− 0.4 98Ru γ 0.745, 0.652 - 99Tc trace 2.111×105 y β− 0.294 99Ru 99mTc syn 6.01 h IT 0.142, 0.002 99Tc γ 0.140 - Technetium is the chemical element with atomic number 43 and symbol Tc. -

Rhenium and Technetium III

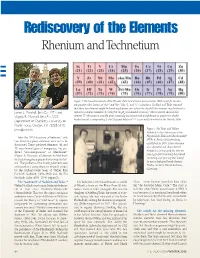

Rediscovery of the Elements Rhenium and Technetium III Figure 1. The transition metals of the Periodic Table had all been discovered by 1923 except for the eka- manganeses (also known as “eka-” and “dvi-”Mn, “1” and “2” in Sanskrit). Noddack and Tacke reasoned that these two elements might be found in platinum ores (where the shaded blue elements may be found as 6 James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and impurities) and/or columbite (Fe,Mn)(Nb,Ta)2O6 (red shaded elements). Their research showed that Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, element 75 (rhenium) is actually most commonly associated with molybdenum in nature (see double 27,28 Department of Chemistry, University of headed arrow), corresponding to the “diagonal behavior” occasionally observed in the Periodic Table. North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, [email protected] Figure 2. Ida Tacke and Walter Noddack in their laboratory at the After the 1923 discovery of hafnium,1f only Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt two transition group elements were yet to be (PTR) in Berlin-Charlottenburg, discovered. These predicted elements (43 and established in 1887, where rhenium 75) were homologues of manganese, the pre- was separated and characterized. dicted “eka-manganeses” of Mendeleev1c Noddack is posing with his ever-pre- (Figure 1). However, all attempts to find them sent cigar and is wearing his stained in crude manganese preparations ended in fail- laboratory coat proving that indeed ure.2 The problem of the missing elements was he was a dedicated bench-chemist. addressed in a comprehensive research project Photo, courtesy, Wesel Archives, by the husband-wife team of Walter Karl Germany. -

The Women Behind the Periodic Table Brigitte Van Tiggelen and Annette Lykknes Spotlight Female Researchers Who Discovered Elements and Their Properties

COMMENT follow the Madelung rule. Although scan- differentiates it from calcium is a 3d one, even physicists and philosophers still need to step dium’s extra electron lies in its 3d orbital, though it is not the final electron to enter the in to comprehend the gestalt of the periodic experiments show that, when it is ionized, it atom as it builds up. table and its underlying physical explana- loses an electron from 4s first. This doesn’t In other words, the simple approach to tion. Experiments might shed new light, make sense in energetic terms — textbooks using the aufbau principle and the Made- too, such as the 2017 finding that helium say that 4s should have lower energy than 3d. lung rule remains valid for the periodic table can form the compound Na2He at very high Again, this problem has largely been swept viewed as a whole. It only breaks down when pressures11. The greatest icon in chemistry under the rug by researchers and educators. considering one specific atom and its occu- deserves such attention. ■ Schwarz used precise experimental pation of orbitals and ionization energies. spectral data to argue that scandium’s 3d The challenge of trying to derive the Eric Scerri is a historian and philosopher orbitals are, in fact, occupied before its 4s Madelung rule is back on. of chemistry at the University of California, orbital. Most people, other than atomic Los Angeles, California, USA. spectroscopists, had not realized this THEORIES STILL NEEDED e-mail: [email protected] before. Chemistry educators still described This knowledge about electron orbitals does 1. -

Recognizing Rhenium

in your element Recognizing rhenium Rhenium and technetium not only share the same group in the periodic table, but also have some common history relating to how they were — or indeed weren’t — discovered. Eric Scerri explains. henium lies two places below known element, namely –1, 0, +1, +2 and so manganese in group 7 of the periodic on all the way up to +7 — the last of which Rtable and its existence was predicted is its most common oxidation state. It is also by Mendeleev in 1869. In fact, when his the metal that led to the discovery of the periodic system was first published, group first metal–metal quadruple bond. In 1964, 7 was rather unique because it contained Albert Cotton and co-workers in the USA only one element known at the time — Y discovered the existence of such a Re–Re manganese — and had at least two gaps RAPH quadruple bond in the form of the rhenium G 2– below it. The first gap was eventually filled ion, [Re2Cl8] (ref. 7). 1 by element 43, technetium , with the second HOTO A large quantity of rhenium is made gap being filled by element 75, rhenium. into super-alloys to be used for parts in jet Rhenium was the first of these two new engines. Typically for a transition metal, group-7-elements to be discovered — in rhenium also acts a catalyst for many 1925 — and accepted by the scientific reactions. For example, a combination community. In the course of an arduously of rhenium and platinum comprise the ISTOCKPHOTO / CC-P ISTOCKPHOTO long extraction, Walter Noddack, Ida Tacke © catalyst of choice in the very important (later Noddack) and Otto Berg obtained just process of making lead-free and high-octane one gram of rhenium after they processed 1939 when Hahn, Strassmann and Meitner petrol. -

Enrico Fermi

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES E N R I C O F ERMI 1901—1954 A Biographical Memoir by S A M U E L K . A LLISON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1957 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ENRICO FERMI 1901-1954 BY SAMUEL K. ALLISON NRICO FERMI, destined to be the first man to achieve the con- E trolled release of nuclear energy, was born in Rome on Sep- tember 29, 1901. His father, Alberto Fermi, was employed in the administration of the Italian railroads, finally rising to the position of division head. His mother, who had been Ida de Gattis, was a school teacher before her marriage. There were three children, of whom two, Enrico and Maria, who was two years his senior, survived to adulthood. Fermi's higher education began in November, 1918, when he entered the Reale Scuola Normale of Pisa where, because of his obvious promise, he had obtained a fellowship. He received the degree of Doctor of Physics, magna cum laude, from Pisa in 1922, presenting for his thesis some experimental work on X-rays.1 From the list of his publications we see that during his student days he was already working on problems in relativistic electrodynamics. Fermi next spent seven months at Gottingen, which was at that time at the pinnacle of its fame in physics. He had been awarded a fellowship from the Italian Ministry of Public Instruction. -

A Tale of Seven Elements, by Eric Scerri. Scope: Accessible

This article was downloaded by: [T&F Internal Users], [Anna Walton] On: 21 July 2014, At: 12:58 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Physics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcph20 A Tale of Seven Elements, by Eric Scerri D.W. Jonesa a Applied Sciences, University of Bradford, Bradford, UK Published online: 08 May 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: D.W. Jones (2014) A Tale of Seven Elements, by Eric Scerri, Contemporary Physics, 55:3, 257-258, DOI: 10.1080/00107514.2014.910273 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00107514.2014.910273 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.