Chapter 4.4 Vegetation and Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014 In the pages that follow are treatments that have been revised since the publication of the Jepson eFlora, Revision 1 (July 2013). The information in these revisions is intended to supersede that in the second edition of The Jepson Manual (2012). The revised treatments, as well as errata and other small changes not noted here, are included in the Jepson eFlora (http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html). For a list of errata and small changes in treatments that are not included here, please see: http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/JM12_errata.html Citation for the entire Jepson eFlora: Jepson Flora Project (eds.) [year] Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on month, day, year] Citation for an individual treatment in this supplement: [Author of taxon treatment] 2014. [Taxon name], Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, [URL for treatment]. Accessed on [month, day, year]. Copyright © 2014 Regents of the University of California Supplement II, Page 1 Summary of changes made in Revision 2 of the Jepson eFlora, December 2014 PTERIDACEAE *Pteridaceae key to genera: All of the CA members of Cheilanthes transferred to Myriopteris *Cheilanthes: Cheilanthes clevelandii D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris clevelandii (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes cooperae D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris cooperae (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes covillei Maxon changed to Myriopteris covillei (Maxon) Á. Löve & D. Löve, as native Cheilanthes feei T. Moore changed to Myriopteris gracilis Fée, as native Cheilanthes gracillima D. -

Taricha Rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges Author(S): Sean B

Discovery of a New, Disjunct Population of a Narrowly Distributed Salamander (Taricha rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges Author(s): Sean B. Reilly, Daniel M. Portik, Michelle S. Koo, and David B. Wake Source: Journal of Herpetology, 48(3):371-379. 2014. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1670/13-066 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/13-066 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 48, No. 3, 371–379, 2014 Copyright 2014 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Discovery of a New, Disjunct Population of a Narrowly Distributed Salamander (Taricha rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges 1 SEAN B. REILLY, DANIEL M. PORTIK,MICHELLE S. KOO, AND DAVID B. WAKE Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, California 94720 USA ABSTRACT. -

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society Harry Baldwin and Thomas Fry - 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Aims and Objectives: .................................................................................................................................................. 4 How to achieve set objectives: ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sharing knowledge of experience gained: ....................................................................................................................... 4 Map of Places Visited: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Itinerary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background to Oaks .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Cosumnes River Preserve ........................................................................................................................................ -

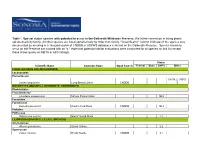

Table *. Special Status Species with Potential to Occur in the Galbreath Wildlands Preserve

Table *. Special status species with potential to occur in the Galbreath Wildlands Preserve. We follow convention in listing plants aphabetically by family. All other species are listed alphabetically by order then family. "Quad Search" column inidicates if the species was documented as occuring in a 16 quad search of CNDDB or USFWS databases centered on the Galbreath Preserve. Species known to occur on the Preserve are marked with an "x." (Note that potential habitat evaluations were conducted for all species on this list except those showing only an MBTA or ABC listings). Status Scientific Name Common Name Quad Search Federal State CNPS Other FUNGI (LICHENS AND MUSHROOMS) Lecanoraeles Parmeliaceae G4 S4.2, USFS: Usnea longissima Long-Beard Lichen CNDDB S BRYOPHYTA (MOSSES, LIVERWORTS, HORNWORTS) Fissidentales Fissidentaceae Fissidens pauperculus Minute Pocket Moss 1B.2 Funariales Funariaceae Entosthodon kochii Koch's Cord Moss CNDDB 1B.3 Pottiales Pottiaceae Didymodon norrisii Norris' Beard Moss 2.2 LILIOPSIDA (GRASSES, LILLIES, ORCHIDS) Alismataceae Alisma gramineum Grass Alisma 2.2 Cyperaceae Carex comosa Bristly Sedge CNDDB 2.1 Carex saliniformis Deceiving Sedge CNDDB 1B.2 Lilaceae Allium peninsulare var. franciscanum Franciscan Onion CNDDB 1B.2 Calochortus raichei The Cedars Fairy-Lantern CNDDB 1B.2 Erythronium revolutum Coast Fawn Lily CNDDB 2.2 Fritillaria roderickii Roderick's Fritillary CNDDB E 1B.1 Orchidaceae Piperia candida White-Flowered Rein Orchid CNDDB 1B.2 Poaceae Dichanthelium lanuginosum var. thermale Geysers Dichanthelium E 1B.1 Glyceria grandis American Manna Grass 2.3 Pleuropogon hooverianus North Coast Semaphore Grass CNDDB T 1B.1 Potamogetonaceae Potamogeton epihydrus ssp. nuttallii Nuttall's Ribbon-Leaved Pondweed 2.2 LILIOPSIDA (GRASSES, LILLIES, ORCHIDS) Asteraceae Hemizonia congesta ssp. -

Biological Resources Report City of Fort Bragg Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgrade

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES REPORT CITY OF FORT BRAGG WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT UPGRADE 101 West Cypress Street (APN 008-020-07) Fort Bragg Mendocino County, California prepared by: William Maslach [email protected] August 2016 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES REPORT CITY OF FORT BRAGG WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT UPGRADE 101 WEST CYPRESS STREET (APN 008-020-07) FORT BRAGG MENDOCINO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA PREPARED FOR: Scott Perkins Associate Planner City of Fort Bragg 416 North Franklin Street Fort Bragg, California PREPARED BY: William Maslach 32915 Nameless Lane Fort Bragg, California (707) 732-3287 [email protected] Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... iv 1 Introduction and Background ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Work ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Location & Environmental Setting ................................................................................................ 1 1.4 Land Use ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1.5 Site Directions .............................................................................................................................. -

Monitoring Aquatic Amphibians and Invasive Species in the Mediterranean Coast Network, 2013 Project Report Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Monitoring Aquatic Amphibians and Invasive Species in the Mediterranean Coast Network, 2013 Project Report Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MEDN/NRDS—2014/715 ON THE COVER California newt (Taricha torosa) Photograph by: National Park Service Monitoring Aquatic Amphibians and Invasive Species in the Mediterranean Coast Network, 2012 Project Report Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MEDN/NRDS—2014/715 Kathleen Semple Delaney Seth P. D. Riley National Park Service 401 W. Hillcrest Dr. Thousand Oaks, CA 91360 October 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California Volume 1 of 2 – Introduction, Methods, and Results Prepared by: California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program California Native Plant Society Vegetation Program For: The Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District The Sonoma County Water Agency Authors: Anne Klein, Todd Keeler-Wolf, and Julie Evens December 2015 ABSTRACT This report describes 118 alliances and 212 associations that are found in Sonoma County, California, comprising the most comprehensive local vegetation classification to date. The vegetation types were defined using a standardized classification approach consistent with the Survey of California Vegetation (SCV) and the United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) system. This floristic classification is the basis for an integrated, countywide vegetation map that the Sonoma County Vegetation Mapping and Lidar Program expects to complete in 2017. Ecologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Native Plant Society analyzed species data from 1149 field surveys collected in Sonoma County between 2001 and 2014. The data include 851 surveys collected in 2013 and 2014 through funding provided specifically for this classification effort. An additional 283 surveys that were conducted in adjacent counties are included in the analysis to provide a broader, regional understanding. A total of 34 tree-overstory, 28 shrubland, and 56 herbaceous alliances are described, with 69 tree-overstory, 51 shrubland, and 92 herbaceous associations. This report is divided into two volumes. Volume 1 (this volume) is composed of the project introduction, methods, and results. It includes a floristic key to all vegetation types, a table showing the full local classification nested within the USNVC hierarchy, and a crosswalk showing the relationship between this and other classification systems. -

Blue Oak Plant Communities of Southern

~ United States ~ Department Blue Oak Plant Communities of Southern of Agriculture Forest Service San Luis Obispo and Northern Santa Bar Pacific Southwest Research Station bara Counties, California General Technical Report PSW-GTR-139 Mark I. Borchert Nancy D.Cunha Patricia C. Kresse Marcee L. Lawrence Borchert. M:1rk I.: Cunha. N,mcy 0.: Km~,e. Patr1c1a C.: Lawrence. Marcec L. 1993. Blue oak plan! communilies or:.outhern San Luis Ob L<ipo and northern Santa Barbara Counties, California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-139. Albany. CA: P:u:ilic Southwest Rcsc:arch Stution. Forest Service. U.S. Dcpurtment of Agriculture: 49 p. An ccologic:11clu,-sili.::uion '),,cm h:b Ileen developed for the Pacifil' Southwest Region of the Forest Service. As part of that c1a....,11ica1ion effort. blue oak rQ11('rrn., tlo11i;lusi1 / woodlands and forests ol ~out hem San Lub Ohi,po and northern Santa Barham Countie, in LO!> Padre!> Nationul Forest were cl:",ilicd imo i.\ plant communitic, using vegetation colkctcd from 208 plot:.. 0. 1 acre e:ach . Tim.'<.' di,tinct region, of vegetation were 1dentilicd 111 the ,tudy :1rea: Avcn:1lc,. Mirnndn Pinc Moun11,ln :ind Branch Mountnin. Communitie.., were dassilied ,eparntel) for plot, in each region. Each region ha, n woodland community thut occupies 11:u orgently slopmg bcnt·he..,.1oc,lopc~. and valley bo110111s. Thc,:c rnmmunitics possess a reltuivcly high proportion oflarge trcc, ( 2: I!( an. d.b.h.l 311d appcarro be heavily gnu cd. In s•ach region an extensive woodland or fore,t communit) covers modcr:uc , lope, with low ,olar in,ol:11io11 . -

Russian River Estuary Management Project Draft

4.0 Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures 4.4 Biological Resources 4.4.1 Introduction This section describes biological resources, with focus on terrestrial and wetland resources, and assesses potential impacts that could occur with implementation of the Russian River Estuary Management Project (Estuary Management Project or proposed project). Fisheries resources are addressed in Section 4.5, Fisheries. Terrestrial and wetland resources include terrestrial, wetland, and non-fisheries-related species, sensitive habitats or natural communities, special-status plant and animal species, and protected trees. Impacts on terrestrial and wetland resources are analyzed in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) significance criteria (CEQA Guidelines, Appendix G). For impacts determined to be either significant or potentially significant, mitigation measures to minimize or avoid these impacts are identified. Information Sources and Survey Methodology The primary sources of information for this analysis are the existing biological resource studies and reports prepared for the Russian River Estuary (Estuary) (Heckel, 1994; Merritt Smith Consulting, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000; Sonoma County Water Agency [Water Agency; SCWA in references] and Merritt Smith Consulting 2001; SCWA, 2006; SCWA and Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods, 2009). These reports, incorporated by reference, present the methods and results of vegetation classification and mapping, fish and invertebrate sampling, amphibian surveys, and observations of bird and pinniped1 numbers and behavior, as well as other sampling efforts (e.g., water quality sampling) conducted in the Russian River Estuary. In addition to the reports listed above, information was obtained from conservation and management plans and planning documents prepared for lands within the project vicinity (Prunuske Chatham, Inc., 2005; California Department of Parks and Recreation [State Parks], 2007), as well as the U.S. -

Effects of Introduced Mosquitofish and Bullfrogs on the Threatened California Red-Legged Frog

Effects of Introduced Mosquitofish and Bullfrogs on the Threatened California Red-Legged Frog SHARON P. LAWLER,*‡ DEBORAH DRITZ,* TERRY STRANGE,† AND MARCEL HOLYOAK* *Department of Entomology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616–8584, U.S.A. †San Joaquin County Mosquito and Vector Control District, 7759 South Airport Way, Stockton, CA 95206, U.S.A. Abstract: Exotic species have frequently caused declines of native fauna and may contribute to some cases of amphibian decline. Introductions of mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) and bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) are suspected to have caused the decline of California red-legged frogs (Rana aurora draytonii). We tested the ef- fects of mosquitofish and bullfrog tadpoles on red-legged frog tadpoles in spatially complex, speciose commu- nities. We added 720 hatchling red-legged frog tadpoles to each of 12 earthen ponds. Three ponds were con- trols, 3 were stocked with 50 bullfrog tadpoles, 3 with 8 adult mosquitofish, and 3 with 50 bullfrogs plus 8 mosquitofish. We performed tests in aquaria to determine whether red-legged frog tadpoles are preferred prey of mosquitofish. Mosquitofish fed on a mixture of equal numbers of tadpoles and either mosquitoes, Daphnia, or corixids until , 50% of prey were eaten; then we calculated whether there was disproportionate predation on tadpoles. We also recorded the activity of tadpoles in the presence and absence of mosquitofish to test whether mosquitofish interfere with tadpole foraging. Survival of red-legged frogs in the presence of bullfrog tadpoles was less than 5%; survival was 34% in control ponds. Mosquitofish did not affect red-legged frog sur- vival, even though fish became abundant (approximately 1011 per pond). -

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group SIERRA NEWT Taricha sierrae Family: SALAMANDRIDAE Order: CAUDATA Class: AMPHIBIA A075 Written by: S. Morey Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Updated by: CWHR Staff May 2013 and Dec 2018 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The Sierra newt is found the length of the Sierra, primarily in the foothills; an isolated population also occurs near the headwaters of Shasta Reservoir in Shasta Co. A few populations are also known from the floor of the Central Valley. Occurs primarily in valley- foothill hardwood, valley-foothill hardwood-conifer, coastal scrub and mixed chaparral, but is also known from annual grassland and mixed conifer types. Elevation range extends from near sea level to about 1830 m (6000 ft) (Jennings and Hayes 1994). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Postmetamorphic juveniles and terrestrial adults take earthworms, snails, slugs, sowbugs, and insects (Stebbins 1972). Adult males at breeding ponds have been shown to take the eggs and hatching larvae of their own species (Kaplan and Sherman 1980) late in the breeding season, the eggs of other amphibians and trout, as well as adult and larval aquatic insects, small crustaceans, snails, and clams (Borell 1935). Aquatic larvae eat many small aquatic organisms, especially crustaceans. Cover: Terrestrial individuals seek cover under surface objects such as rocks and logs, within hollowed out trees, or in mammal burrows, rock fissures, or human-made structures such as wells. Aquatic larvae find cover beneath submerged rocks, logs, debris, and undercut banks. Reproduction: Eggs are laid in small firm clusters on the submerged portion of emergent vegetation, on submerged vegetation, rootwads, unattached sticks, and on the underside of cobbles off the bottom.