A New Beginning 1975-1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

644 CANADA YEAR BOOK Governments. the Primary Basis For

644 CANADA YEAR BOOK governments. The primary basis for the division is important issue of law that ought to be decided by the found in Section 2 ofthe criminal code. The attorney court. Leave to appeal may also be given by a general of a province is given responsibility for provincial appellate court when one of itsjudgments proceedings under the criminal code. The attorney is sought to be questioned in the Supreme Court of general of Canada is given responsibility for criminal Canada. proceedings in Northwest Territories and Yukon, and The court will review cases coming from the 10 for proceedings under federal statutes other than the provincial courts of appeal and from the appeal criminal code. Provincial statute and municipal division ofthe Federal Court of Canada. The court is bylaw prosecutions are the responsibility ofthe also required to consider and advise on questions provincial attorney general. referred to it by the Governor-in-Council. It may also Prosecutions may be carried out by the police or advise the Senate or the House of Commons on by lawyers, depending on the practice ofthe attorney private bills referred to the court under any rules or general responsible. If he prosecutes using lawyers, orders of the Senate or of the House of Commons. the attorney general may rely on full-time staff The Supreme Court sits only in Ottawa and its lawyers, or he may engage the services of a private sessions are open to the public. A quorum consists of practitioner for individual cases. five members, but the full court of nine sits in most A breakdown of criminal prosecution expenditures cases; however, in a few cases, five are assigned to sit, by level of government in 1981-82 shows that 75% and sometimes seven, when a member is ill or was paid by the provinces (excluding Alberta), 24% disqualifies himself Since most of the cases have by the federal government and 1% by the territories. -

La Clinique De Médiation De L'université

LE MAGAZINE DES JURISTES DU QUÉBEC 4$ Volume 24, numéro 6 La Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal et ses partenaires : se mobiliser pour l’accès à la justice Dans l’ordre habituel de gauche à droite, de bas en haut : Mme Rielle Lévesque (Coordonnatrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Sherbrooke) , Dr Maya Cachecho (Chercheure post- doctoral et coordonnatrice scientifique du Projet de recherche ADAJ), Me Laurent Fréchette (Président du Comité de gouvernance et d’éthique, Chambre des notaires du Québec), Pr Pierre-Claude Lafond (Professeur à l’Université de Montréal, membre du Groupe RéForMa et membre du Comité scientifique de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Me Hélène de Kovachich (Juge administratif et fondatrice-directrice de la Clinique de médiation de l’Université de Montréal), Pr Marie-Claude Rigaud (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et directrice du Groupe RéForMa), Pr Catherine Régis (Professeure à l’Université de Montréal et membre du Groupe RéForMa), Me Ariane Charbonneau (Directrice générale d’Éducaloi), Mme Anja-Sara Lahady (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), Mme Laurie Trottier-Lacourse (Assistante de recherche 2018-2019), L’Honorable Henri Richard (Juge en chef adjoint à la chambre civile de la Cour du Québec), M Serge Chardonneau (Directeur général d’Équijustice), Mme Laurence Codsi (Présidente du Comité Accès à la Justice), Me Nathalie Croteau (Secrétaire-trésorière de l’IMAQ), Me Marie Annik Gagnon (Juge administratif coordonateur section des affaires sociales, TAQ), -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:21 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A. Macdonald The Legacy of Roncarelli v. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Article abstract L’héritage de l’affaire Roncarelli c. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Given the inclination of legal scholars to progressively displace the meaning of Volume 55, Number 3, September 2010 a judicial decision from its context toward abstract propositions, it is no surprise that at its fiftieth anniversary, Roncarelli v. Duplessis has come to be URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1000618ar interpreted in Manichean terms. The complex currents of postwar society and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1000618ar politics in Quebec are reduced to a simple story of good and evil in which evil is incarnated in Duplessis’s “persecution” of Roncarelli. See table of contents In this paper the author argues for a more nuanced interpretation of the case. He suggests that the thirteen opinions delivered at trial and on appeal reflect several debates about society, the state and law that are as important now as half a century ago. The personal socio-demography of the judges authoring Publisher(s) these opinions may have predisposed them to decide one way or the other; McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill however, the majority and dissenting opinions also diverged (even if unconsciously) in their philosophical leanings in relation to social theory ISSN (internormative pluralism), political theory (communitarianism), and legal theory (pragmatic instrumentalism). Today, these dimensions can be seen to 0024-9041 (print) provide support for each of the positions argued by Duplessis’s counsel in 1920-6356 (digital) Roncarelli given the state of the law in 1946. -

Architypes Vol. 15 Issue 1, 2006

ARCHITYPES Legal Archives Society of Alberta Newsletter Volume 15, Issue I, Summer 2006 Prof. Peter W. Hogg to speak at LASA Dinners. Were rich, we have control over our oil and gas reserves and were the envy of many. But it wasnt always this way. Instead, the story behind Albertas natural resource control is one of bitterness and struggle. Professor Peter Hogg will tell us of this Peter W. Hogg, C.C., Q.C., struggle by highlighting three distinct periods in Albertas L.S.M., F.R.S.C., scholar in history: the provinces entry into Confederation, the Natural residence at the law firm of Resource Transfer Agreement of 1930, and the Oil Crisis of the Blake, Cassels & Graydon 1970s and 1980s. Its a cautionary tale with perhaps a few LLP. surprises, a message about cooperation and a happy ending. Add in a great meal, wine, silent auction and legal kinship and it will be a perfect night out. Peter W. Hogg was a professor and Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School at York University from 1970 to 2003. He is currently scholar in residence at the law firm of Blake, Cassels & Canada. Hogg is the author of Constitutional Law of Canada Graydon LLP. In February 2006 he delivered the opening and (Carswell, 4th ed., 1997) and Liability of the Crown (Carswell, closing remarks for Canadas first-ever televised public hearing 3rd ed., 2000 with Patrick J. Monahan) as well as other books for the review of the new nominee for the Supreme Court of and articles. He has also been cited by the Supreme Court of Canada more than twice as many times as any other author. -

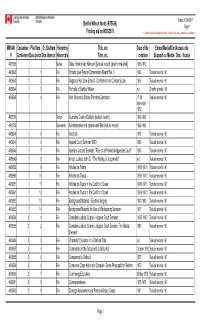

Bertha Wilson Fonds (R15636) Finding Aid No MSS2578 MIKAN

Date: 21/06/2017 Bertha Wilson fonds (R15636) Page 1 Finding aid no MSS2578 Y:\App\Impromptu\Mikan\Reports\Description_reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers_simplelist.im MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent/Media/Dim/Access cde # Contenant Dos./pièce Dos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 4938705 Series Osler, Hoskin and Harcourt [textual record, graphic material] 1965-1972 4939542 1 1 File Ontario Law Reform Commission Report No. 1 1965 Textual records / 90 4939543 1 2 File Osgoode Hall Law School - Conference on Company Law 1965 Textual records / 90 4939544 1 3 File Portraits of Bertha Wilson n.d Graphic (photo) / 90 4939545 1 4 File York Un ive rsity Estate Planning Seminars 17-18 Textual records / 90 November 1972 4938706 Series Supreme Court of Ontario [textual record] 1962-1982 4938708 Sub-series Administrative and operational files [textual record] 1962-1982 4939546 1 5 File Abortion 1976 Textual records / 90 4939547 1 6 File Appeal Court Seminar 1980 1980 Textual records / 90 4939548 1 7 File Apellate Judges' Seminar, "Role of a Provincial Appellate Court" 1980 Textual records / 90 4939549 1 8 File Arnup, Justice John D., "The Writing of Judgments" n.d Textual records / 90 4939550 1 9 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939550 1 10 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 11 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict of Laws [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 12 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict -

Ian Bushnell*

JUstice ivan rand and the roLe of a JUdge in the nation’s highest coUrt Ian Bushnell* INTRODUCTION What is the proper role for the judiciary in the governance of a country? This must be the most fundamental question when the work of judges is examined. It is a constitutional question. Naturally, the judicial role or, more specifically, the method of judicial decision-making, critically affects how lawyers function before the courts, i.e., what should be the content of the legal argument? What facts are needed? At an even more basic level, it affects the education that lawyers should experience. The present focus of attention is Ivan Cleveland Rand, a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1943 until 1959 and widely reputed to be one of the greatest judges on that Court. His reputation is generally based on his method of decision-making, a method said to have been missing in the work of other judges of his time. The Rand legal method, based on his view of the judicial function, placed him in illustrious company. His work exemplified the traditional common law approach as seen in the works of classic writers and judges such as Sir Edward Coke, Sir Matthew Hale, Sir William Blackstone, and Lord Mansfield. And he was in company with modern jurists whose names command respect, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Benjamin Cardozo, as well as a law professor of Rand at Harvard, Roscoe Pound. In his judicial decisions, addresses and other writings, he kept no secrets about his approach and his view of the judicial role. -

Ideology and Judging in the Supreme Court of Canada

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 26 Issue 4 Volume 26, Number 4 (Winter 1988) Article 4 10-1-1988 Ideology and Judging in the Supreme Court of Canada Robert Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Courts Commons Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Martin, Robert. "Ideology and Judging in the Supreme Court of Canada." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 26.4 (1988) : 797-832. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol26/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Ideology and Judging in the Supreme Court of Canada Abstract The purpose of this article is to advance some hypotheses about the way the Supreme Court of Canada operates as a state institution. The analysis is based on the period since 1948. The first hypothesis is that the judges of the Supreme Court of Canada belong to the dominant class in Canadian society. The second hypothesis is that they contribute to the dominance of their class primarily on the ideological plane. Keywords Canada. Supreme Court--Officials and employees--History; Judges; Canada Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This article is available in Osgoode Hall Law Journal: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol26/iss4/4 IDEOLOGY AND JUDGING IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA* By ROBERT MARTIN" The purpose of this article is to advance some hypotheses about the way the Supreme Court of Canada operates as a state institution. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

MSS2101 Graphic 1--4; 108--110.Xlsx

John Sopinka fonds MG31-E120 Finding aid no MSS2101 vols. 1--110; 07447; TCS 01429 R1312 Instrument de recherche no MSS2101 Hier. lvl. Media Label File Item Title Scope and content Vol. Dates Niv. Support Étiquette Dossier Pièce Titre Portée et contenu hier. John Sopinka fonds Activities as Justice at the Supreme Court of Canada Bench books 22 June 1989 - 7 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 1 Bench Book No. 1 1989 6 Dec. 1989 - 23 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 2 Bench Book No. 2 1990 26 Mar. 1990 - 12 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 1 3 Bench Book No. 3 1990 29 Oct. 1990 - 27 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 1 4 Bench Book No. 4 1991 28 Feb. 1991 - 4 July File Textual MG31-E120 1 5 Bench Book No. 5 1991 1 Oct. 1991 - 9 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 6 Bench Book No. 6 1991 10 Dec. 1991 - 25 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 7 Bench Book No. 7 1992 26 May 1992 - 11 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 2 1 Bench Book No. 8 1992 25 Jan. 1993 -27 May File Textual MG31-E120 32 1 Bench Book No. 9 1993 31 May 1993- 26 Jan. File Textual MG31-E120 32 2 Bench Book No. 10 1994 27 Jan. 1994 - 4 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 32 3 Bench Book No. 11 1993 4 Oct. 1994 - 23 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 32 4 Bench Book no. 12 1995 24 Feb. 1995 - 3 Nov. File Textual MG31-E120 32 5 Bench Book No. -

Télécharger En Format

ARTICLE DE LA REVUE JURIDIQUE THÉMIS On peut se procurer ce numéro de la Revue juridique Thémis à l’adresse suivante : Les Éditions Thémis Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville Montréal, Québec H3C 3J7 Téléphone : (514)343-6627 Télécopieur : (514)343-6779 Courriel : [email protected] © Éditions Thémis inc. Toute reproduction ou distribution interdite disponible à : www.themis.umontreal.ca Untitled 5/18/05 4:48 PM La Revue juridique Thémis / volume 28 - numéros 2 et 3 Jean Beetz, Souvenirs d'un ami Gérard La Forest[1] Jean Beetz était l'un de mes plus grands amis. Nos vies ont suivi un cours parallèle. En effet, nous avons fréquenté Oxford au même moment, nous avons tous deux enseigné le droit, pendant une brève période en même temps à l'Université de Montréal, et nous avons été doyens exactement au même moment. Nous avons tous deux participé très activement au processus constitutionnel dans les années 1960 et 1970, travaillant en étroite collaboration à la rédaction de la Charte de Victoria. Puis, nous avons tous deux été nommés juges, lui à la Cour d'appel du Québec et moi à celle du Nouveau-Brunswick, pour enfin nous retrouver collègues à la Cour suprême du Canada. Bien que nous ayons tous deux fréquenté Oxford, Jean de 1950 à 1952 et moi de 1949 à 1951, chose curieuse je ne me souviens pas de lui à cette époque, ni lui ne se souvenait-il de moi. Toutefois, c'est à Oxford qu'il rencontrait un autre étudiant, Julien Chouinard. -

Co Supreme Court of Canada

supreme court of canada of court supreme cour suprême du canada Philippe Landreville unless otherwise indicated otherwise unless Landreville Philippe by Photographs Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0J1 K1A Ontario Ottawa, 301 Wellington Street Wellington 301 Supreme Court of Canada of Court Supreme ISBN 978-1-100-21591-4 ISBN JU5-23/2013E-PDF No. Cat. ISBN 978-1-100-54456-4 ISBN Cat. No. JU5-23/2013 No. Cat. © Supreme Court of Canada (2013) Canada of Court Supreme © © Cour suprême du Canada (2013) No de cat. JU5-23/2013 ISBN 978-1-100-54456-4 No de cat. JU5-23/2013F-PDF ISBN 978-0-662-72037-9 Cour suprême du Canada 301, rue Wellington Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0J1 Sauf indication contraire, les photographies sont de Philippe Landreville. SUPREME COURT OF CANADA rom the quill pen to the computer mouse, from unpublished unilingual decisions to Internet accessible bilingual judgments, from bulky paper files to virtual electronic documents, the Supreme Court of Canada has seen tremendous changes from the time of its inception and is now well anchored in the 21st century. Since its establishment in 1875, the Court has evolved from being a court of appeal whose decisions were subject to review by a higher authority in the United Kingdom to being the final court of appeal in Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada deals with cases that have a significant impact on Canadian society, and its judgments are read and respected by Canadians and by courts worldwide. This edition of Supreme Court of Canada marks the retirement of Madam Justice Marie Deschamps, followed by Fthe recent appointment of Mr.