Philosophical Synthesis in the Early Period Plays of Eugene O’Neill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

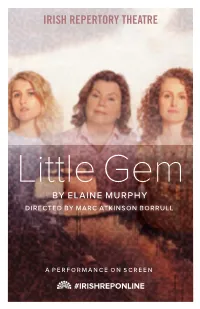

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

Biographies (396.2

ANTONELLO MANACORDA conducteur italien • Formation o études de violon entres autres avec Herman Krebbers à Amsterdam o puis, à partir de 2002, deux ans de direction d’orchestre chez Jorma Panula. • Orchestres o 1997 : il crée, avec Claudio Abbado, le Mahler Chamber Orchestra o 2006 : nommé chef permanent de l’ensemble I Pomeriggi Musicali à Milaan o 2010 : nommé chef permanent du Kammerakademie Potsdam o 2011 : chef permanent du Gelders Orkest o Frankfurt Radio Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Sydney Symphony, Orchestra della Svizzera Italia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Stavanger Symphony, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Hamburger Symphoniker, Staatskapelle Weimar, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse & Gothenburg Symphony • Fil rouge de sa carrière o collaboration artistique de longue durée avec La Fenice à Venise • Pour la Monnaie o dirigeerde in april 2016 het Symfonieorkest van de Munt in werk van Mozart en Schubert • Projets récents et futurs o Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Don Giovanni & L’Africaine à Frankfort, Lucio Silla & Foxie! La Petite Renarde rusée à la Monnaie, Le Nozze di Figaro à Munich, Midsummer Night’s Dream à Vienne et Die Zauberflöte à Amsterdam • Discographie sélective o symphonies de Schubert avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical - courroné par Die Welt) o symphonies de Mendelssohn également avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical) • Pour en savoir plus o http://www.inartmanagement.com o http://www.antonello-manacorda.com CHRISTOPHE COPPENS Artiste et metteur -

Apply for a Livestock Dealer License

Steven W. Troxler North Carolina Department of Agriculture R. Douglas Meckes, DVM State Veterinarian Commissioner and Consumer Services Veterinary Division APPLICATION FOR NEW LIVESTOCK DEALER LICENSE 1. Date of Application: (MM/DD/YR) 2. Form of Organization ☐ Individual ☐ Corporation ☐ Association ☐ Partnership 3. Name of Applicant: 4. Applicant’s Street Address (Physical address, No PO box numbers) 5. Applicant’s City 6. Applicant’s State 7. Applicant’s Zip Code 8. Applicant’s County 9. Applicant’s Phone Number ☐ Landline ☐ Mobile 10. Applicant’s Email Address 11. Business Name 12. Business Street Address (Physical address, No PO box numbers) 13. Business City 14.Business State 15. Business Zip Code 16. Business County 17.Mailing Address (if different from number 12) 18. City 19.State 20. Zip Code 21. County 22.Business Phone number 23.Business Email address 24. Business Mobile Number 25. Business Premise ID 1030 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-1030 (919) 707-3250 (919) 733-2277 www.ncagr.gov An Equal Opportunity Employer Version May 2018 1 | P a g e 26. Animals to be purchased and sold when license is approved: □ Cattle □ Sheep □ Goats □ Swine □ Equine □ Other 27.List of all persons (not including applicant) who will be operating under this livestock dealer license. Contact the State Veterinarian if there are any changes in the information provided. Last Name First Name Phone Number Email address Street Address (Physical address, No City Zip Code PO box numbers) State County Last Name First Name Phone Number Email address Street Address (Physical address, No City Zip Code PO box numbers) State County Last Name First Name Email Address Phone Number Street Address (Physical address, No City Zip Code PO box numbers) State County 02 NCAC 52E.0201 DAY AND TIME OF SALE: The regularly scheduled auction sales at public livestock auction markets shall be held on a designated day or days, Monday through Friday. -

Hello, My Name Is Igor and I Am a Russian by Birth. I Have Read A

Added 31 Jan 2000 "Hello, My name is Igor and I am a Russian by birth. I have read a lot about Islam, I have Arabic and Chechen friends and I read a lot about the Holy Koran and its teaching. I resent the drunkenness and stupidity of the Russian society and especially the gorrilla soldiers that are fighting against the noble Mujahideen in Chechnya. I would like to become a Muslim and in connection with this I would like to ask you to give me some guidance. Where do I go in Moscow for help in becoming a Muslim. Inshallah I can accomplish this with your help." [Igor, Moscow, Russia, 28 Jan 2000] "May Allah help you brothers. I am from Kuwait. All Kuwaitis are with you. We hope for you to win this war, inshallah very soon. If you want me to do anything for you, please tell me. I really feel ashamed sitting in Kuwait and you brothers are fighting the kuffar (disbelievers). Please tell me if we can come there with you, can we come?" [Brothers R and R, Kuwait, 30 Jan 2000] "Salam my Brave Mujahadeen who are fighting in Chechnya and the ones administrating this web site. Every day I come to this site several time just to catch a glimpse of the beautiful faces whom Allah has embraced shahadah and to get the latest news. I envy you O Mujahadeen, tears run into my eyes every time I hear any news and see any faces on this site. My beloved brothers, Allah has chosen you to reawaken Muslims around the world. -

Legislative Schedule

21st Calendar Day EIGHTY-FIRST OREGON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2021 Regular Session JOINT Legislative Schedule MONDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2021 SENATE OFFICERS PETER COURTNEY, President LORI L. BROCKER, Secretary of the Senate JAMES MANNING, JR, President Pro Tempore CYNDY JOHNSTON, Sergeant at Arms HOUSE OFFICERS TINA KOTEK, Speaker TIMOTHY G. SEKERAK, Chief Clerk PAUL HOLVEY, Speaker Pro Tempore BRIAN MCKINLEY, Sergeant at Arms SENATE CAUCUS LEADERS ROB WAGNER, Majority Leader FRED GIROD, Republican Leader ELIZABETH STEINER HAYWARD, Deputy Majority Leader CHUCK THOMSEN, Deputy Republican Leader LEW FREDERICK, Majority Whip LYNN FINDLEY, Assistant Republican Leader SARA GELSER, Majority Whip DENNIS LINTHICUM, Republican Whip MICHAEL DEMBROW, Assistant Majority Leader KATE LIEBER, Assistant Majority Leader HOUSE CAUCUS LEADERS BARBARA SMITH WARNER, Majority Leader CHRISTINE DRAZAN, Republican Leader ANDREA SALINAS, Majority Whip DANIEL BONHAM, Deputy Republican Leader JULIE FAHEY, Deputy Majority Whip DUANE STARK, Republican Whip PAM MARSH, Assistant Majority Leader KIM WALLAN, Assistant Republican Whip RACHEL PRUSAK, Assistant Majority Leader BILL POST, Assistant Deputy Republican Leader JANEEN SOLLMAN, Assistant Majority Leader SHELLY BOSHART DAVIS, Assistant Republican Leader CEDRIC HAYDEN, Assistant Republican Leader RICK LEWIS, Assistant Republican Leader NO FLOOR SESSIONS SCHEDULED TODAY SENATE CONVENES AT 11:00 AM ON THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2021 HOUSE CONVENES AT 11:00 AM ON TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 LEGISLATIVE ACCESS NUMBERS: LEGISLATIVE INTERNET -

Biography of Eugene O'neill

Biography of Eugene O’Neill Trevor M. Wise Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born on October 16, 1888, at the Barrett hotel in New York city, New York, son of James o’Neill, a well-known matinee idol, and Mary Ellen (Ella) Quinlan. Much of O’Neill’s youth was spent in the wings of the theater as he toured the country with his parents and older brother Jamie, watching his father perform his most famous role—the Count of Monte Cristo. When not touring the country with his family, O’Neill attended Catholic boarding school at St. Aloysius Academy at Mount Saint Vincent in the Bronx borough of New York. he then spent four years at Betts Academy, a non-sectarian prep school in Stamford, Connecticut. O’Neill spent the summers with his family at the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, Connecticut, the only permanent home O’Neill knew as a child. in 1903, at the age of fifteen, o’Neill became aware of his mother’s morphine addiction and was introduced to alcohol by his brother Jamie, setting him on a path of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse. in the fall of 1906, o’Neill enrolled in princeton University, only to be expelled in the following spring for his poor academic per- formance. in october 1909, o’Neill secretly married Kathleen Jenkins, his first of three wives. Shortly after the wedding, o’Neill set sail for honduras to prospect for gold, but found none. While abroad, O’Neill lived the life of a waterfront derelict, working odd jobs and drinking heavily, until he contracted malaria and was forced to return to the United States. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 Nationaltheatre.Org.Uk Find Us Online How to Book the Plays

This cover was created with the Lighting Department. Lighting is used to create moments of stage magic. The choices a Lighting Designer makes about how a set and actors are lit have a major impact on the mood and atmosphere of a scene. The National’s Lighting department deploys everything from flood or spotlight to complex automated lights, controlled via a lighting data network. Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 nationaltheatre.org.uk Find us online How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm See p29 for Sunday and holiday opening times Hedda Gabler LOVE Amadeus Playing from 5 December 6 December – 10 January Playing from 19 October Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm for the following week’s performances Day Tickets £15 / £18 tickets available in person on the day of the performance No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Peter Pan The Red Barn A Pacifist’s Guide to Playing from 16 November 6 October – 17 January the War on Cancer 14 October – 29 November Access symbols used in this brochure Captioned Touch Tour British Sign Language Relaxed Performance Audio-Described TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre NT Future is Partner for Sponsored by in partnership -

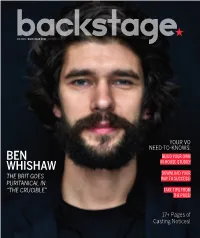

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Hay Harvest Well Behind Schedule

eaSier Prairie carcass liGhthouSe trackinG Viewing tower at the edge BIXS to be more user friendly » Page 12 of ancient lake » Page 22 August 22, 2013 SERVING mANITOBA FARMERS SINCE 1925 | Vol. 71, No. 34 | $1.75 mAnitobAcooperAtor.cA feedlot association to let market sort out zilmax flap hay harvest well Potential impact on cow- calf producers uncertain By Daniel Winters behind schedule co-operator staff yson Foods’ decision to Endless parade of summer showers has affected hay quality, stop buying cattle given EXTREME MOISTURE and for many the first cut still hasn’t been rolled up T the feed additive Zilmax is sending waves through the beef industry, but Canada’s feedlot sector is determined to stay the course. “Our position is to follow sci- ence and let the market decide. Full stop,” said Brian Walton, chair of the National Cattle Feeders Association. His organization doesn’t track use of Zilmax or other beta- agonists, but Walton said it’s “pretty common” in feedlots in Western Canada, as is a slightly different growth promoter by a competing manufacturer called OptaFlexx. “Science has already proven that it’s safe to use and effective, so it should be the choice of the producers and their customers,” said Walton. The announcement of Tyson’s new policy was followed by the showing of a video by a JBS USA official at a recent industry conference in Denver. Taken at a JBS plant, it shows animals having difficulty walking and demonstrating signs of lame- ness. Animal welfare expert Temple Grandin, who was present at the event, said the s ee FEEDLOTS on page 6 » photo: stockexchange By Daniel Winters The extra moisture has increased yields The late start has cut into yields for co-operator staff “a bit,” but a prolonged hot and dry spell tame hay, and native hay acres around is needed to bale first-cut alfalfa and get Lake Manitoba are down due to the lin- he wet summer has created end- the second cut underway, he said. -

O'neill and Nietzsche: the Making of a Playwright and Thinker

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 O'Neill and Nietzsche: The Making of a Playwright and Thinker Regina Fehrens Poulard Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Poulard, Regina Fehrens, "O'Neill and Nietzsche: The Making of a Playwright and Thinker" (1974). Dissertations. 1385. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1385 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Regina Fehrens Poulard 0 'NEILL AND NIEI'ZSCHE: THE MAKING OF A PI.A'YWRIG HT AJ.'JD THDl'KER by Regina Foulard A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1974 ACKNOWLEIGMENTS I wish to thank the director of llzy" dissertation, Dr. Stanley Clayes, and llzy" readers, Dr. Rosemary Hartnett and Dr. Thomas Gorman, for their kind encouragement and generous help. ii PREFACE Almost all the biographers mention Nietzsche's and Strindberg's influence on O'Neill. However, surprisingly little has been done on Nietzsche and O'Neill. Besides a few articles which note but do not deal exhaustively with the importance of the German philosopher1 s ideas in the plays of O'Neill, there are two unpublished dissertations which explore Nietzsche's influence on O'Neill.